opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

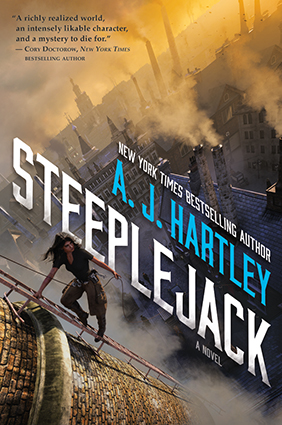

opens in a new window Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an extended excerpt from Steeplejack, the first in A.J. Harvey’s fantasy series inspired by 19th century South Africa. Keep an eye out for Firebrand, the sequel coming June 6th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an extended excerpt from Steeplejack, the first in A.J. Harvey’s fantasy series inspired by 19th century South Africa. Keep an eye out for Firebrand, the sequel coming June 6th.

Seventeen-year-old Anglet Sutonga lives repairing the chimneys, towers, and spires of the city of Bar-Selehm. Dramatically different communities live and work alongside each other. The white Feldish command the nation’s higher echelons of society. The native Mahweni are divided between city life and the savannah. And then there’s Ang, part of the Lani community who immigrated over generations ago as servants and now mostly live in poverty on Bar-Selehm’s edges.

When Ang is supposed to meet her new apprentice Berrit, she finds him dead. That same night, the Beacon, an invaluable historical icon, is stolen. The Beacon’s theft commands the headlines, yet no one seems to care about Berrit’s murder—except for Josiah Willinghouse, an enigmatic young politician. When he offers her a job investigating his death, she plunges headlong into new and unexpected dangers.

Meanwhile, crowds gather in protests over the city’s mounting troubles. Rumors surrounding the Beacon’s theft grow. More suspicious deaths occur. With no one to help Ang except Josiah’s haughty younger sister, a savvy newspaper girl, and a kindhearted herder, Ang must rely on her intellect and strength to resolve the mysterious link between Berrit and the missing Beacon before the city descends into chaos.

CHAPTER 1

The last person up here never made it down alive, but there was no point thinking about that. Instead, I did what I always did—focused on the work, on the exact effort of muscle, the precise positioning of bone and boot that made it all possible. Right now, that meant pushing hard with my feet against the vertical surface of one wall while my shoulders strained against another, three feet away. I was horizontal, or as near as made no difference, the two brick faces forming an open shaft. If I relaxed even fractionally, I would die on the cobbles eighty feet below.

So don’t.

It really was that simple. You figured out what you needed to do to stay alive, and you did it, however your sinews screamed and your head swam, because giving in meant falling, and falling meant death.

I was working the old cement factory on Dyer Street, bypassing a rusted-out portion of the ladder to the roof on my way to rebuilding the chimney itself, the top rim of which had shed bricks till it looked like a broken tooth. I braced myself and inched my way up, brick by brick, till I reached the section of ladder that was still intact and tested it with one cautious hand.

Seems solid enough.

I pivoted and swung my body weight onto the lowest rung. For a moment, I was weightless in empty air, seesawing between life and death, and then I was safe on the ladder and climbing at ten times my previous speed.

I am Anglet Sutonga—Ang to those who think they know me—and I am a steeplejack, one of perhaps six or seven dozen who work the high places of Bar-Selehm. Some say I am the best since the Crane Fly himself, half a century ago. They might be right at that, but boasting—even if it stays in your head—makes you careless, and the one thing you really can’t afford up there on the spires and clock towers and chimneys is carelessness. If I was good, it was because at seventeen I’d lived longer than most.

I moved easily over the roof to the point where the great round tower of the chimney reached up into the murky sky, tested the ladder, and began the slow climb to the top. Most of the really tall factory chimneys—the hundred- or two-hundred-footers—taper as they go, but they generally flare at the top, sometimes with an elaborate cap that juts out. These make for interesting climbing. You scale straight up; then you have to kick out and back, hanging half upside down over nothing, till you get over the cap and onto the upper rim.

There are no ladders at the top. If you leave them in place, the anchor holes in the mortar will trap moisture and crack the brick, so after each job, the steeplejack takes the ladders down and fills the holes. In this case, the ladder up to the cap was still there because two months ago, Jaden Saharry—the boy who had been working the chimney—fell, and no one had finished the job.

He was thirteen.

Most steeplejacks are boys. When they are young, it doesn’t much matter what sex they are, because the work is just getting up inside the fireplaces of big houses and climbing around in the chimneys with a brush and scraper. It is all about being small, and less likely to get stuck. But as the steeplejacks grow too big for domestic chimneys and graduate to the factory stacks, strength and agility become key. Then, since no one is looking for a bride who can outlift him, the girls are gradually given other things to do with their daylight hours. I was the only girl over fourteen in the Seventh Street gang, and I maintained my position there by climbing higher and working harder than the boys. And, of course, by not falling.

A new boy—Berrit—was supposed to be up here, waiting for me to show him the ropes, but there was no sign of him. Not a good start, though in truth, a part of me was relieved.

Today I would want to be alone with my thoughts as much as possible.

Ten feet below the great brick overhang of the cap, I cleared the last mortared hole with my chisel and hooked one leg over the top of the ladder so I could use both hands. I took a wooden dowel from my pocket and pressed it into the cavity with the heel of my hand, then drew an iron spike—what we call a dog—from the satchel slung across my chest, positioned its tip against the protruding end of the dowel, and drove it in with three sharp blows of my lump hammer. The action meant straightening up and back, and I felt the strain in my belly muscles as I leaned out over the abyss. The ground, which I could see upside down if I craned back far enough, was a good two hundred feet below. Between me and it, a pair of vultures was circling, their black, glossy wings flashing with the pale light of dawn. I’d been higher, but there comes a point when a few more feet doesn’t really make any difference. Dead is dead, whether you fall from fifty feet or three hundred.

The dog split the dowel peg and anchored in the brick. I tested it, then ran the rope to pull the last length of ladder into place, ignoring the tremble of fatigue in my arms as I hooked and lashed it firm. I took a breath, then climbed the newly positioned rungs, which leaned backwards over the chimney cap, angling my boots and gripping tightly with my hands. Carefully, like a trapeze artist, I hauled my body up, out, and over. I was used to being up high, but it was only when I had to navigate the chimney caps that I felt truly unnerved.

And thrilled.

I didn’t do the job just because I was good at it. I liked it up here by myself, high above the world: no Morlak looking over my shoulder, no boys testing how far they had to go before I threw a punch, no wealthy white folk curling their lips as if I put them off their breakfast.

I clambered over and sat inside the broad curve of the chimney’s fractured lip, conscious of my heart slowing to something like normal as I gazed out across the city. From here I could count nearly a hundred chimneys like this one. Some taller, some squat, some square sided or stepped like pyramids, but mostly round like this, pointing up into the sky like great smoking guns, dwarfing the minarets and ornamental roofs that had survived from former ages.

It had once been beautiful, this bright, hot land rolling down to the sea. In places, it still was—wide and open savannahs where the sveld beasts grazed and the clavtar stalked; towering mountains, their topmost crags lost in cloud; and golden, palm-fringed beaches.

And sky. Great swatches of startling, empty blue where the sun burned high during the day, and night brought only blackness and a dense scattering of stars.

That’s how it had been, and how it still was not so very far away. But not here. Not in Bar-Selehm. Here were only iron and brick and a thick, pungent smoke that hung in perpetual shroud over the pale city, shading its ancient domed temples and stately formal buildings. A couple of miles inland, down by the Etembe market, the air was ripe with animal dung, with the mouthwatering aroma of antelope flesh roasted over charcoal braziers, with cardamom, nutmeg, and pepper and, when the wind blew in from the west, the dry but fertile fragrance of the tall grass that bent in the breeze all the way to the mountains. In the opposite direction was the ocean, the salt air redolent with fish and seaweed and the special tang of the sea. But here there was only smoke. Even all the way up the chimneys, above the city, and at what should have been the perfect vantage on the minarets of Old Town, and on the courts and monuments of the Finance District, I could see little through the brown fog, and though I wore a ragged kerchief over my mouth and nose, I could still taste it. When I spat, the slime was spotted with black flakes.

“If the work doesn’t kill you,” Papa used to say, “the air will.”

I sat on the dizzying top, my legs hooked over the edge, and below me nothing for two hundred feet but the hard stone cobbles that would break a body like a hundred hammers.

I studied the cracked and blackened bricks around the chimney’s rim. Three whole rows were going to have to come out, which meant ferrying hods of new bricks and mortar up and down the ladders. It was a week’s work or more. I was faster than the others on the team, and though that generally earned me little but more work, I might make an extra half crown or two. Morlak didn’t like me, but he knew what I was worth to him. And if I didn’t do the job, if Sarn or Fevel took over, they’d mess it up, or miss half of what needed replacing, and we’d all suffer when the chimney cap crumbled.

I gazed out over the city again, registering … something.

For a moment it all felt odd, wrong, and I paused, trying to process the feeling. It wasn’t just my mood. It was a tugging at the edge of consciousness like the dim awareness of an unfamiliar scent or a half memory. I moved into a squat, hands down on the sooty brick, eyes half-closed, but all I got was the fading impression that the world was somehow … off.

I frowned, then reached back and worked the tip of my chisel into the crumbled mortar. Steeplejacks don’t have much time for imagination except, perhaps, in fiction, and since I’m the only one I know who reads books, I’m not really representative. Three sharp blows with the hammer, and the brick came free, splintering in the process, so that a flake flew out and dropped into the great black eye of the chimney.

I cursed. Morlak would let me know about it if I filled the grate at the bottom with debris. I gathered the other remains and scooped them into my satchel, then repositioned the chisel and got on with the job.

No one choses to be a steeplejack. A few are poor whites and orphans, some are blacks who fall foul of the city and cannot return to a life among the herds on the savannah, but most are Lani like me, lithe and brown, hazel eyed, and glad of anything that puts food in their mouths. A few, men like Morlak—it is always men—make it into adulthood and run the gangs, handing off the real work to the kids while they negotiate the contracts and count the profits.

I didn’t mind it so much. The heights didn’t bother me, and the alternative was scrubbing toilets, working stalls in the market, or worse. At least I was good at this. And on a clear day, when the wind parted the smog, Bar-Selehm could still be beautiful.

I set the hammer down. The satchel was getting full and I had only just begun. Standing up, I turned my back toward the ladder, and for a moment, I felt the breeze and steadied myself by bending my knees slightly. In that instant it came again, that sense that the world was just a little wrong. And now I knew why.

There was something missing.

Normally, my view of the city from hereabouts would be a gray-brown smear of rooftops and chimney spikes, dark in the gloom, save where a single point of light pricked the skyline, bathing the pale, statuesque structures of the municipal buildings with a glow bright and constant as sunlight. Up close it was brilliant, hard to look at directly, even through the smoke of the chimneys. By night it kept an entire block and a half of Bar-Selehm bright as day, and even in the densest smogs it could be seen miles out to sea, steering sailors better than the cape point lighthouse.

It was known as the Beacon. The light was housed in a crystal case on top of the Trade Exchange, a monument to the mineral on which the city had been built, and a defiantly public use of what was surely the most valuable item in the country. The stone itself was said to be about the size of a man’s head, and was therefore the largest piece of luxorite ever quarried. It had been there for eighty years, over which time its light had barely diminished. Its value was incalculable.

And now it was gone. I strained my eyes, disbelieving, but there could be no doubt. The Beacon was not dimmed or obscured by the smoke. It was gone, and with that, the world had shifted on its axis, a minute adjustment that altered everything. Even for someone like me, who was used to standing tall in dangerous places, the thought was unsettling. The Beacon was a constant, a part of the world that was just simply there. That it wasn’t felt ominous. But it also felt right, as if the day should be commemorated with darkness.

Papa.

I touched the coin I wore laced round my neck, then took a long breath. There was still no sign of Berrit, and my satchel needed emptying.

After moving to the top of the ladder, I reached one leg over, then the other. There was a little spring in the wood, but the dogs I had hammered into the brickwork were tight, and the ladder felt sure under my weight. Even so, I was careful, which was just as well, because I was halfway over the perilous cap when someone called out.

The suddenness of it up there in the silence startled me. One hand, which had been moving to the next rung, missed its mark, and for a moment, I was two-thirds of the way to falling. I righted myself, grabbed hold of the ladder, and stared angrily down, expecting to see Berrit, the new boy, made stupid by lateness.

But it wasn’t, and my annoyance softened.

It was Tanish, a Lani boy, about twelve, who had been with the gang since his parents died three years ago. He was scrambling recklessly up, calling my name still, his face open, excited.

“Stop,” I commanded. “Wait for me on the roof.”

He looked momentarily wounded, then began to climb down.

Tanish was the closest thing I had to an apprentice. He followed me around, learning the tricks of the trade and how to survive in the gang, gazing at me with childish admiration. He was a sweet kid, too sweet for Seventh Street, and sometimes it was my job to toughen him up.

“Never call up to me like that,” I spat as soon as we were both at the foot of the chimney. “Idiot. I nearly lost my grip.”

“Not you, Ang,” the boy answered, flushed and sheepish. “You’ll never fall.”

“Not till I do,” I said bleakly. “What are you doing here? I thought you were working the clock tower on Dock Street?”

“Finished last night,” said Tanish, pleased with himself. “Superfast, me.”

“And it still tells the right time?”

Tanish beamed. Last time he had been working a clock with Fevel, they had left the timepiece off by three and a half hours. When the owner complained, they climbed back up and reset it twice more, wildly wrong both times, too embarrassed to admit that neither one of them could tell time. Eventually Morlak had done them a diagram and they had had to climb up at double the usual speed to set the mechanism. Even so, they had left the clock four minutes slow and its chime still tolled the hour after every other clock in the city, so that the gang jokingly referred to Tanish Time which meant, simply, late. .

“Well?” I demanded, releasing the hair I keep tied back while I work. It fell around my shoulders and I ran my fingers roughly through it. “What’s so important?”

“It’s your sister,” said Tanish, unable to suppress his delight that he was the one to bring the news. “The baby. It’s time.”

I closed my eyes for a moment, my jaw set. “Are they sure?” I asked. “I wasted half of yesterday sitting around out there—”

“The runner said they’d brought the midwife.”

Today of all days, I thought. Of course it would be today.

“Right,” I said half to myself. “Tell Morlak I’m going.”

My pregnant sister, Rahvey, was three years my senior. We did not like each other.

“Morlak says you can’t go,” said Tanish. “Or—” He thought, trying to remember the gang leader’s exact words. “—if you do, you better be back by ten and be prepared to work the late shift.”

That was a joke. Rahvey and her husband, Sinchon, lived in a shanty on the southwest side of the city, an area traversed by minor tributaries of the river Kalihm, and populated by laundries, water haulers, and dyers. It was known as the Drowning, and it would take me an hour to get there on foot.

Well, there was no avoiding it. I would have to deal with Morlak when I got back.

Morlak was more than a gang leader. In other places, he might have been called a crime lord, and crossing him was, as the Lani liked to say, “hazardous to the health,” but since he provided Bar-Selehm’s more respectable citizens with a variety of services, he was called simply a businessman. That gave him the kind of power he didn’t need to reinforce with a stick and brass knuckles, and ordinarily I would not dream of defying him.

But family was family: another infuriating Lani saying.

I had two sisters: Vestris, the eldest and most glamorous, who I barely saw anymore; and Rahvey, who had raised me while Papa worked, a debt she would let me neither pay nor forget.

“Take my tools back for me,” I said, unslinging the satchel.

“You’re going?” said Tanish.

“Seems so,” I answered, walking away. I had taken a few steps before I remembered the strangeness I had felt up there on the chimney and stopped to call back to him. “Tanish?”

The boy looked up from the satchel.

“What happened to the Beacon?” I asked.

The boy shrugged, but he looked uneasy. “Stolen,” he said.

“Stolen?”

“That’s what Sarn said. It was in the paper.”

“Who would steal the Beacon?” I asked. “What would be the point? You couldn’t sell it.”

Tanish shrugged again. “Maybe it was the Grappoli,” he said. Everything in Bar-Selehm could be blamed on the Grappoli, our neighbors to the northwest. “I’ll go with you.”

“Don’t you have to get to work?”

“I’m supposed to be cleaning Captain Franzen,” he said. “Supplies won’t be here till lunchtime.”

Captain Franzen was a glorified Feldish pirate who had driven off the dreaded Grappoli three hundred years ago. His statue stood atop a ceremonial pillar overlooking the old Mahweni docks.

“You can come,” I said, “but not into the birthing room, so you won’t see my sister perform her maternity.”

He gave me a quizzical look.

“The stage missed a great talent when my sister opted to stay home and have babies,” I said, grinning at him.

He brightened immediately and fell into step beside me, but a few strides later stopped suddenly. “Forgot my stuff,” he said. “Wait for me.”

I clicked my tongue irritably—Rahvey would complain about how late I was even if I ran all the way—and stood in the street, registering again the void where the glow of the Beacon should be. It was like something was missing from the air itself. I shuddered and turned back to the factory wall.

“Come on, Tanish!” I called.

The boy was standing beneath the great chimney, motionless. In fact, he wasn’t so much standing as stooping, frozen in the act of picking up his little duffel of tools. He was staring fixedly down the narrow alley that ran along the wall below the chimney stack. I called his name again but he didn’t respond, and something in his uncanny stillness touched an alarm in my head. I began moving toward him, my pace quickening with each step till I was close enough to seize him by his little shoulders and demand what was keeping him.

But by then I could see it. Tanish turned suddenly into my belly, clinging to me, his eyes squeezed shut, his face bloodless, and over his shoulder I saw the body in the alley, knowing—even from this distance—that Berrit, the boy I had been waiting for, had not missed our meeting after all.

CHAPTER 2

Berrit was Lani, like Tanish and me. He had been, maybe, ten. I had met him once over our communal meal at the Seventh Street weavers’ shed two nights ago, when Morlak thrust him in front of me, barked his name, and told me he would be shadowing me for a few days. I had just grunted, nodding at the boy, who looked subdued and frightened. I had meant to take him aside later on, introduce myself properly—without Morlak standing over us, ready with his clumsy jokes designed to embarrass me—but I never did. Somehow, when I wasn’t looking, he had slunk away to sleep, unnoticed. It was a smart and useful skill to have on Seventh Street, inconspicuousness, and I privately commended him for it, but since I was summoned to Rahvey’s bedside the following day, I hadn’t set eyes on the boy again until I saw his broken body huddled by the factory wall.

Tanish was distraught. He had spent more time with the new boy, and had never seen the result of a long fall before. I sent him to get help, and he fled, eyes streaming. Driven by an inexplicable sense of failure, of guilt, I forced myself to look.

I had seen death before. For someone of my age and background, living in the highest and—figuratively speaking—lowest places of Bar-Selehm, it was impossible not to. That does not mean that I was immune to the grief and horror of death, and if you do not know what a fall from a great height does to a human body, thank whatever god you believe in and hope you never find out. I will not be the one to show you.

He looked so very small. Under the horror of how he had died I felt the stirrings of something deeper and more awful: something like grief, which drained my soul and brought to my eyes the tears that I had not allowed myself to shed in front of Tanish. He needed me to be strong, and I had been, but now I was alone and might crack open the door to my feelings. I felt pressure from the other side, like deep water held in check by a dam, and I squeezed the door shut once more.

I took refuge in thought, in reason, which kept feelings at bay. The drop from the chimney was sheer. There was nothing on which the boy might have cut himself before hitting the cobbled ground, so the sharp, precise incision, no more than an inch across and located directly over his spine, was strange. It would need to be cleaned and studied by people who knew what such things meant, but it raised a possibility.

The fall did not kill him.

The idea came before I could dodge it, and hung in my head like the absent Beacon, blazing.

Around his neck he wore a copper pendant on a thong, a pretty thing with a sun rendered in gold enamel on a cobalt blue disk. I removed it carefully and pocketed it. There would be someone who had loved him. They should get it.

“You found him?” asked the uniformed policeman who attended the ambulance orderlies. He was tall, white, with an overly tended mustache that was barely the right side of comic. He spoke to me in Feldish, which I spoke fluently, albeit with a Lani inflection. If you worked in Bar-Selehm, you had to, even the Lani when we left our own communities. It was the language of the whites, and as such it had become the language of government, of finance, trade, law, and all things that mattered. Lani like Rahvey’s husband, Sinchon, who knew only a few words of it, were virtually unemployable beyond the Drowning. I spoke it and, thanks to Vestris, even read it.

I’m not an eloquent person. I read a lot but I spend my days up with the roosting flying foxes and the silver-winged night crows, who aren’t great conversationalists. At night I’m surrounded by adolescent boys, who are worse. I love words, but mostly they stay in my head, especially in the presence of authority.

“I was with the boy who found him, yes,” I said.

“His name is Berrit?”

“Yes.”

“Last name?”

“I don’t know.”

“He’s a steeplejack?”

“Apprentice. This was his first day.”

“And he was going to work with you?”

“Yes.”

“And you are?”

“Anglet Sutonga. I work for Morlak.” I frowned, and he gave me a hard look.

“What?” he demanded.

“Nothing, sir,” I said.

“You were thinking something,” he pressed. “What? I won’t ask again.”

“Just…” I faltered. “I wondered why you weren’t writing this down.”

“Got a good memory, me,” said the policeman, gazing off down the alley. “And the city has other things to think about today. Get it all up, lads!” he called to the ambulance men. “There’s a tap on the wall. Hose off the street when you’re done.”

A vulture had settled in the alley and was watching us, waiting. I shouted at it and it flapped a few paces away, bobbing its bald head.

“Pictures,” I blurted out.

“What?” said the policeman again.

“Photographs,” I said, eyes down, abashed. “You’ve started taking pictures at crime scenes. I saw them in the paper.”

“So?”

“They haven’t taken any,” I said, risking a look into his face.

“Crime scenes,” he echoed as if I were unusually stupid. “This was an accident.”

“But…” I hesitated.

“But what?”

I took a breath. “The body. There’s a knife wound on the back.”

“Expert, are you?” said the policeman, giving me a sour look this time. “Steeplejack and detective, eh? Impressive. I thought girls like you had other ways of making your money.” He smirked, then gazed off down the street again. His eyes were straying to where the Beacon should have been but wasn’t. For all his casualness, he looked troubled.

And that, I thought, was that. There would be no investigation, no real questions asked, not for a Lani street brat, particularly on a day when the city’s most recognizable landmark had vanished. I put my hand in my pocket and was surprised to find the copper pendant on its leather thong. I took it out. It was a small thing, and for all the care of the workmanship, it was close to worthless.

The thought sent a shard of pain through my chest, and I had to pause and breathe again before squeezing my eyes—

and the dam

shut, and pocketed it once more.

Tanish was waiting for me, sitting in the shade, his knees drawn up tight to his skinny chest. He got to his feet as he saw me push through the huddle of gawkers craning for a glimpse of blood, elbowing aside a man in fancy shoes and a linen suit, who turned abruptly and walked away. Even in my haste to get to Tanish, I noted the speed with which the man left, the focus, the economy of motion, and found myself wondering how long he had been watching and why.

I didn’t have the heart to tell Tanish to go home. Sarn had come, he said. Tanish had given him our tools. He would come back soon with Morlak. I didn’t want to be around then, so I set off for my sister’s house, Tanish trailing silently at my heels like a lost dog.

Everyone was rattled by the absence of the Beacon. You could see them gazing at the spire on top of the Trade Exchange, and there was a more than usually frantic crowd at the newspaper stand on Winckley Street. I scanned the headlines, which brayed the obvious: that the Beacon had gone. Beyond that, the papers knew nothing, and the report was more hysteria than news.

“You gonna buy that?” demanded the street vendor, a black girl with her hair pulled back so tight that her forehead looked strained.

“With what?” I asked with a hollow smile. The girl glared unsympathetically and I let go of the paper, backing away from the throng and moving round the corner and into Vine Street.

“My mother taught me to read,” said Tanish. It was just something to say, I think, but once he had got it out it sounded forlorn.

“My sister taught me,” I answered, trying to sound cheerful. “Not Rahvey. Vestris.”

“How come I’ve never seen her?”

“She’s too fancy for the likes of you,” I said, unable to suppress a genuine smile now.

“Fancy?”

“Glamorous,” I said. “Rich.”

“I’d like to see her one day,” said Tanish. He had heard me talk of Vestris before and had caught a little of my reverence for her. “What does she do?”

“Do?”

“For, you know, a job?” he asked. “I mean, why is she so rich if she grew up like you?”

“Oh, she’s just sort of special,” I said airily. “She’s not rich because of where she works.”

“Why, then?”

I laughed, waving the question away. “She’s just different from the rest of us,” I concluded.

“Special,” he said, uncertain.

“Exactly.”

And I felt what I always felt when I thought of Vestris: a kind of vague privilege that I knew her. It was like sitting in a shaft of sunlight on a cool day, a private warming glow that made me the envy of everyone around me.

“One time when we were little,” I said, “the mine where Papa worked had been closed and he had no work, which meant we had no money. Vestris brought food home every night. Rahvey asked her how she was paying for it, and you know what she said?”

“What?”

“She said, ‘I just ask nicely. I explain that my sisters are hungry, and people give us food.’”

“So she was begging.”

“No,” I said. “It wasn’t like that. She’s just the kind of person people want to please. I can’t explain it.”

Tanish looked at me for more, but I said nothing.

The city was walled, and though urban sprawl had long since outgrown the old fortifications, the walls still marked the limits of Bar-Selehm proper and they were routinely patrolled. It was clear as we approached the West Gate, however, that something different was going on this morning. One of the ancient iron-bound doors had actually been closed—the first time since the city had quarantined itself during a cattle death outbreak three years ago—and people were being funneled through a gamut of dragoons. The soldiers wore their scarlet jackets and feathered helmets in spite of the mounting heat, and they carried rifles with sword bayonets. Two were mounted on striped orleks—local, zebralike horses—which stamped and tossed their heads restlessly. The troops on the ground were white, but there were members of one of the black regiments up on the walls.

This too was about the Beacon. Not Berrit.

The soldiers checked papers, but the only people they detained were those carrying bags, baskets, or crates. Me and Tanish, they practically ignored, though I flinched away when one of the orleks stooped toward me, its nostrils flaring. I’m a city girl, and am not good around large animals. Once through the checkpoint, I increased my pace till Tanish was almost running to keep up.

The residential streets of the Drowning had no official names and did not appear on any map, rather coming and going from season to season as the river dwindled and flooded, shifting its course and turning what had been a bustling tent city to marshland. There were no sewer lines but the river in the Drowning. The street corners sprouted ragged produce stands, huddles of itinerant laborers hoping to be hired for a few hours, and makeshift barbecues fashioned from scrap metal and fueled by homemade charcoal. This was where I had grown up. The hut in which I was born had long since turned to firewood and no one could remember exactly where it had stood, but this was, I supposed, home.

Once. When Papa was still alive.

The Drowning smelled different from the industrial heart of the city where I lived now, a sour smell of bodies and animals and rotting vegetables. I preferred the bitter tang of the chimneys, even if it left me hacking till my throat burned, and coated my face and arms with soot. The Drowning stank of poverty, ignorance, and despair.

I hated it.

The Lani aren’t indigenous to the region. We were brought here almost 200 years ago from lands to the east by the whites from the north. My ancestors came as indentured servants, manual laborers and field hands, living separate from both the indigenous Mahweni and the whites. They were never slaves and believed they had settled in Feldesland by choice, keeping to themselves as the northerners conquered, bought, and absorbed more and more of the land from the native blacks. The Lani were neither military nor political, and reasoned that as long as they were left to their own devices, they were better staying out of the disputes and skirmishes during the white settlement of the region. By the time they looked up from their cooking fires to find that they had turned into a squalid and itinerant people living peasant lives, it was too late.

Most of Morlak’s gang came from here or somewhere similarly ragged and decaying. Some of them, like Tanish, still thought of this place as home, and his mood brightened as we reached the first outlying huts and tents.

“I see Mrs. Emtiga’s ass got out again,” he said, amused. “That thing needs an armed guard and a castle wall.”

I laughed, then risked a question. “Berrit was a Drowning boy too, right? You must have been almost the same age.”

A Drowning boy. That’s what they called them, proudly and with no sense of the bitter irony.

Tanish didn’t look at me. “I didn’t remember him till we spoke a few days ago,” he said. “But, yes. I think we played together when we were little. Then he went to the Westside gang and I stayed here till…”

Till Tanish’s mother died.

“Why did he leave Westside?” I went on quickly.

“Got traded,” said Tanish. “Part of a deal involving the Dock Street warehouse and some building supplies.”

So Morlak bought him. That wasn’t supposed to happen, but it did.

“How did he feel about that?” I asked.

Tanish shrugged. “Didn’t seem to care,” he said. “Said he was going to be something big in the Seventh Street gang.”

“He’d been a steeplejack for the Westside boys?”

“Nah,” said Tanish. “He said he’d been a pickpocket, but I think he was really a bootblack. Might have done a bit of thieving on the side, but that wasn’t how he earned his keep. He’d never been up a chimney, inside or out. He pretended not to be, but I think he was scared of heights.”

“So why did he think he was going to be big in the gang?”

“Optimist,” said Tanish bleakly. “Always going on about what he was going to do when his ship came in.”

I nodded thoughtfully, and as Tanish’s face tightened with the memory, I decided to switch direction. “What about you?” I asked, ruffling his hair affectionately. “What will you do when your ship comes in?”

“Ships don’t come in for the likes of us,” he said.

“Sure they do,” I tried, not believing it.

“Then they’ll be rusted-up pieces of kanti,” he said.

I laughed. “Full of rats,” I agreed.

“And holes,” he added. “And sharks would swim in through the holes and live in the hold, ready to bite your legs off as soon as you went aboard.” He grinned at the idea, and that, for the moment, was as good as things were going to get.

Inside the tent city, a gaggle of local women and their kids had already gathered outside the hut. There was a sense of drama brewing in the air, and they paused in their chatter as we approached, nodding at me with caution and watchfulness. Sinchon’s look as I opened the hut’s juddering door was, however, loaded with accusation.

No surprise there.

Sinchon shared his wife’s disdain for his antisocial sister-in-law. He was a hoglike man who scratched a living panning for luxorite in the river above the Drowning. He had found a couple of grains five years ago, but nothing since, and lived mainly off the scraps of minerals he turned up from time to time. The kids laughed at him, because everyone knew there was no luxorite being found anymore, but he still thought I was beneath him.

“Where have you been?” he shot, pausing in the whittling of a stick. “The baby is almost here.”

“I’m here now,” I said.

“Your sister needed you earlier.”

“I was working,” I replied, avoiding his eyes.

And Rahvey hasn’t needed me a day in her life, I added to myself.

“Who’s that?” he asked, gazing past me to where Tanish was loitering on the steps.

“Someone I work with. Used to live here. He’ll help you get some water.”

There was a snatch of conversation from the room beyond the thin lattice door, a woman’s voice. Sinchon looked at the door but did not move. Lani men didn’t go into the delivery room until it was over.

“Hope to the gods it’s not a girl,” he said as I crossed the room.

I said nothing, but I felt the chill grip of the idea inside my chest. Rahvey had had a son who she lost to the damp lung when he was two. She had three girls already. She would not be allowed a fourth.

They dressed it up in other words, but the bald truth was that Lani girls were not considered worth raising. They were married off—expensively—as soon as possible, but the problem wasn’t really about cost. Lani culture was made by men. They were the leaders, the lawmakers, the property holders. Women raised the children, cooked, cleaned, and did as they were told. If they worked outside the home, they were paid less than men for the same job by their Lani bosses, and working for anyone else meant turning your back on your people. Though Morlak and most of his gang were Lani, the mere fact of working in the city proper meant that to most of the people I had grown up with, I had abandoned them. At their best, girls were pretty things used to ally families. At their worst, an annoyance.

Poverty and ignorance have a way of clinging to bad ideas. The worst among what were sanctimoniously clustered as “the Lani way” was the rule that said that no family could have more than three daughters. The first daughter, it was said, was a blessing. The second, a trial. The third, a curse. As a third daughter myself, I felt the full weight of that last piece of wisdom, which was why I spent as little time among “my people” as possible. Rahvey had three girls already. If she gave birth to another, the child would be sent to an orphanage. In the old days, if no suitable mother could be found, more drastic steps would be taken, a grim little secret the appalled white settlers had made illegal. Such practices had, supposedly, ended, but there were accidents during the birthing of unwanted daughters, which people did not scrutinize too closely.

“Is it true, what they are saying?” Sinchon asked, his hand on the door handle.

“About what?” I replied, thinking of Berrit.

“The Beacon,” said Sinchon. His usually impassive face looked uncertain, hunted. “We can’t see it. They are saying someone stole it.”

I frowned, feeling again that sense that the earth had wobbled beneath my feet. “I don’t know,” I said.

“Isn’t that where you work?” he demanded, masking his unease with a contempt with which he was more comfortable.

“It’s not there,” I said. “I don’t know what happened to it, but it’s gone.”

Sinchon’s face set, but he said no more and left.

The inner room was just big enough for a bed and a stove, and the latter had been loaded with coal. It was stiflingly hot, and the air was vinegar sour with sweat. The midwife, kneeling between Rahvey’s splayed legs, shot me a look as I came in, and snapped, “Close the door! You’re letting the cold in.”

There was no cold, but I did as she asked.

At the head of the bed, Rahvey looked surprisingly placid, but when her eyes flicked to mine, her face fell instantly.

I was not the sister she had been waiting for. I never was.

“Pass me that towel,” said Florihn, the midwife. I squatted beside her, but kept my eyes on the wall. “About time you were having one of these yourself,” the woman added.

I had seen her around the camps for years, coming and going with bloodstained napkins and buckets of water. She lost no more babies than was usual, and had birthed me seventeen years ago, but I had never taken to her. I suppose I imagined the midwife’s disappointed announcement of what I was when I had first emerged bawling from my mother. Another girl. I could not, of course, actually remember the moment, but I was sure it had happened, and a small and spiteful part of me hated her for it.

And there was one thing more. My mother had not survived my birth. She had heard me cry, I was told, had held me for a while, but she had lost too much blood, and nothing Florihn had been able to do could save her.

Third daughter, a curse.

So, yes, though the idea made my stomach writhe with the injustice of it, when I looked at Florihn, I could not stifle a pang of guilt.

“Any word from Vestris?” asked Rahvey.

Our idolized elder sister.

My heart skipped a beat at the thought of seeing her.

“We sent to her,” said Florihn, not looking up, “but haven’t heard back yet.”

“She’ll come,” said Rahvey, lying back. “For the naming, if not before. She’ll come.”

It was a statement not of hope but of faith.

I was not so sure. Vestris was twenty-five, eight years my senior, which was enough to mean that we had barely grown up together at all, though my earliest memories were of her—not Rahvey, and certainly not my devoted but illiterate father—reading to me. She had found work at an ambassador’s residence while I was still small. There she had attracted the interest of men far beyond our family’s caste or social station. Our mother had been, I was told, a beautiful woman, and while both Rahvey and I had inherited something of her looks, it was Vestris who drew people’s eyes. In my childish recollections, our eldest sister had been a figure of exquisite and mysterious appeal, and as her social setting improved, so did the wealth of her clothes. She was a society lady now, and her appearance in the Drowning was greeted with the kind of reverent excitement people normally reserved for comets. Rahvey worshipped her.

“Look at this,” said Florihn to me, pointing between Rahvey’s legs. I forced myself to look, though I couldn’t make sense of what I was seeing.

“Is that right?” I managed.

Florihn gave me a smug smile and seemed to wait on purpose, as if driving home my ignorance. “I guess books don’t teach you everything,” she said.

The learning my eldest sister had passed on to me had always been something of a local joke, especially considering what I had opted to do with my life.

Florihn was giving me an inquisitorial stare, and eventually I shrugged.

“Yes, it’s fine,” she said at last. “But there’ll be no baby today.”

“I came because I thought it was happening now.”

Rahvey said nothing, but gave me a defiant look.

“This is a time for family,” said Florihn piously. “You’d know that if you spent more time here.”

I blinked. They didn’t want me around. Not really. They just wanted me to feel bad for not being like them. I felt the certainty of it like a stone in my boot that I couldn’t shake out, a constant irritant that might one day make me lame.

No wonder I preferred life up on the chimneys, alone in the sky.

“I have to go back to work,” I said, rising. “Has anyone…?”

I hesitated and Rahvey gave me a blank look this time.

“Has anyone been to the cemetery?” I asked, my voice carefully neutral.

Rahvey turned away. “We’ve been a little busy,” she said, her voice managing to suggest an outrage she didn’t really feel.

I nodded. “I’ll go,” I said.

“Of course you will,” said Rahvey. And this time the bitterness was real.

CHAPTER 3

On the East Side of the Drowning was an ancient, weather-beaten temple teeming with vervet monkeys and fire-eyed grackles. It was as close to leaving the city as I ever got, a kind of halfway house between the urban sprawl of Bar-Selehm and the wilderness beyond. By day, an elderly priest burned incense and chanted among the weed-choked altars for whoever put a copper coin in his bowl, but by night, the little shrines and funerary markers were haunted by baboons and hyenas. For a city girl like me, it was unnerving, but I had no choice. Two years ago, my father’s remains were buried here.

Papa.

He was a good Lani, a good father, a kindly, brown-eyed giant of a man, quick to grin, to play, to tease. I had loved him with all my heart and missed him every day.

“I’ll always keep you safe, Anglet,” he had said. “I’ll always be there to look after you.”

The only lie he ever told me.

I was already grown up when he died, already working, but till then and in spite of everything I went through in the Seventh Street gang, I had never felt truly alone. Papa had always been there, a buffer between me and my sisters, my work, the world in general, ready with a touch, a word, a smile that calmed my raging blood, dried my tears, and told me that all would yet be well. Always. He was my rock, my consolation, and my joy. When Papa looked at me, the universe made sense, and all the words the others hurled at me fell harmless at my feet or blew away like smoke.

He died in a mining accident with four other Lani men. He was trying to reach two apprentices who had been trapped by a rockfall, but the new passage they opened released a pocket of gas. There was an explosion. It took a week to get to the bodies after the shaft collapsed, and I was not allowed to see him. His remains were burned as is our custom, and the ash strewn over the river, save for one fragment of bone that was interred in the hard, dusty grounds of the temple.

Two years to the day.

I have been alone ever since. I believe the two apprentices were found unharmed.

Tanish came with me to the grave, eyeing me sidelong and careful not to make noise. Partly he was trying to show respect, but it was also the place that left him subdued. He had seen enough death for one day. I would have told him to leave me to my thoughts, but a family of hippos had taken over the riverbank below the temple, and a Lani woman had been killed by one of them when she went to draw water only a couple of weeks before. I didn’t want him wandering alone, so I let him hover awkwardly at my back as I found the marker and knelt down, sitting on my heels.

Someone had placed crimson tsuli flowers on the grave, bound with gold cord. They were fresh and lustrous, hothouse grown at this time of year. Expensive.

Vestris.

It had to be. I felt a quickening of my pulse as I sensed my sister’s presence, and my eyes flashed hungrily around the graveyard as if she might still be there. But she was gone, and my disappointment felt suddenly shameful. Deflated, I adjusted the flowers and focused on the stone marker, feeling young and alone.

Family is family.

Except when it’s gone.

I said nothing, feeling the coin I wore on a thong around my neck.

All steeplejacks wore something that connected them to their past. It was a claim to a version of yourself that wasn’t about the work. Berrit’s had been his sun-disk pendant. Mine was an old copper penny Papa gave me. It had been misstamped and bore the last king’s head on both sides. The Seventh Street boys thought I kept it for luck, because I could flip the coin and always guess correctly what would come up, but I didn’t. I kept it because Papa gave it to me and because when he did, he said, “Because it’s rare. Like you, Ang. One of a kind.”

He thought I was special. I wasn’t, but he believed otherwise, and that almost made it true.

Now I turned the coin over and over in my fingers, and the face embossed on its twin sides became his in my mind so that I pressed it to my lips and closed my eyes like a little kid who thought that wishing might bring him back.

I had never lived in Rahvey’s house, but those refuse-blown streets with the sour smell of goats and the stagnant reed beds by the river were all too familiar. Whenever I went back to the Drowning now, all I found was what was gone, the spaces Papa had left behind him. No wonder I hated the place. It was a land of ghosts, of absences.

I had learned long ago not to cry, no matter the hurt in your hands or your heart. Tears in the city gangs meant fear and weakness, and they were punished without mercy. I knew that, and I knew that after this morning, Tanish needed me to be strong.

But this was hard.

Harder than I had expected. It had been, after all, two years. The grief at first, coupled as it was with shock and horror, had been almost unbearable, but over the subsequent weeks and months, it lessened. In my childish imagination, I figured it would continue to fade, like a distant ship sailing beyond the reach of vision until it disappeared entirely. But it hadn’t, and I saw now, kneeling on the sandy dirt and staring at the roughly carved stone that bore his name, that it never would. I would always be straining to see him, reaching for him, and he would never be there. I would carry his absence like a hole in my heart forever.

I remembered Berrit, a boy I had not known, who died on Papa’s anniversary, and a single tear slid down my nose and fell onto the dusty earth as if I were watering a tiny seedling. I wiped the trace away before turning to Tanish, who was gazing about him, looking glum and a little bored. He had not seen.

I laid a fistful of wild kalla lilies on the grave next to Vestris’s tsuli flowers and set my face to meet the world, but as I half turned to Tanish, someone called.

“Anglet!”

I recognized the girl as one of those who did errands for Florihn, the midwife. “What?” I called back, though I knew what was coming.

“It’s started!” cried the girl.

I followed her to Rahvey’s house, where Sinchon was sitting on the porch, scowling. As I approached, a roar of agony came from inside, a woman’s voice—though one so pressed to the limits of human endurance that I heard no sign of my sister in it. I didn’t speak to Sinchon, but yanked the door open and stepped inside.

It was even hotter than it had been earlier, and Florihn, crouching between my sister’s legs, shot me an irritated look when I entered, as she had the first time. At the far end of the bed, Rahvey’s red, glistening face was a rictus of pain.

As I set my things down, she began to scream again, an unearthly, animal sound like the weancats that prowled the edge of the Drowning when prey in the hinterlands was scarce. I winced, the hair on the back of my neck prickling, but Florihn just grinned.

“That’s right,” she said to Rahvey. “You cry it out.”

As soon as the contraction passed, I said, “I thought there would be no baby today?”

From her place between Rahvey’s legs, Florihn scowled at me, then refocused on Rahvey and said simply, “Now.”

It took no more than five minutes, and I kept my gaze locked on my sister’s face for as much of it as possible. When the baby emerged, I did as I was told, but I couldn’t stop staring at the child.

It was a girl. The fourth daughter.

For a long moment, no one moved or spoke. The baby wailed over Rahvey’s exhausted panting, and I just looked at it, registering the awful truth, so that for a few seconds, it seemed that time had stopped.

At last the midwife seemed to come back to herself. Her face was ashen, but she brought her fluttering hands together and pressed her fingertips, a gesture of composure and resolution, both hard won.

Then she stood up and took a deep, quavering breath. “Where’s my knife?” she asked.

“Wait,” I said. “What are you doing?”

“Cutting the cord,” said Florihn. “What did you think?”

Rahvey gaped, her eyes flicking to the midwife for guidance.

“Then what?” I asked.

There was a moment’s stillness; then the baby began to cry again. The midwife wrapped her in a towel and set the child on the floor before turning on me and speaking in a low whisper. “Fourth daughter,” she said. “You know what that means. Rahvey can’t keep it. It goes to a blood relative or we take it to Pancaris,” said Florihn.

Pancaris was an orphanage run by one of the Feldish religious orders—dour-habited, grim-faced white nuns who raised children to be domestic servants.

“Till she runs away and turns beggar or whore,” I said, looking at the brown, wriggling infant, so small and powerless.

“There’s no other choice,” said Florihn dismissively. “And they’ll teach her what she needs.”

“Like what?” I asked.

Florihn gave me a hard look for my temerity, but she answered. “They’ll teach her to scrub. To cook. To wield a pick or wheel a barrow. Anything else is just making promises you can’t keep. You of all people should know that.”

I looked to Rahvey, but she kept her eyes fixed on Florihn, the way Tanish stares at me to avoid looking down from the chimneys.

“Rahvey,” I said, dragging her gaze to my face. “Maybe there’s another way. Maybe this fourth-daughter business can—”

“Can what?” demanded Florihn.

“I don’t know,” I said, quailing under the woman’s authoritative stare.

My sister gaped some more, at me this time, then looked back to the midwife. She squeezed her eyes shut, and a tear coursed down her cheek. Her grief gave me the courage I needed.

“Maybe we could keep her,” I said, feeling the blood rise in my face.

Florihn blinked, but she maintained a rigid calm. Her eyes became two slits as she considered how to respond. “‘We’?” she said, staring me down. “What will your contribution be to raising an unseemly child? Where will you be when your sister has to raise more money to feed another mouth?” When I said nothing, she added, “Yes, that’s what I thought.”

“Sinchon could look for a different kind of job,” I said unsteadily, but Florihn, reading the panic in Rahvey’s face, cut me off.

“And you’ll tell him that, will you?” she demanded. “You have forgotten everything. This is our way. The Lani way.”

Then it’s a stupid way! I wanted to shout, an old rage spiking in my chest. You should change it.

But faced with Florihn’s baleful glare, the words wouldn’t come out. Rahvey looked cowed, but her eyes wandered back to the mewling infant. I moved to the child, stooped, and gathered her inexpertly into my arms.

“Put it down, Anglet,” said the midwife. “You are only making things harder. This is not helpful. It is cruel.”

I avoided her eyes, crossing to my sister with the child.

Rahvey gazed up at me, and beneath the exhaustion and hesitation, I thought I saw a flicker of something else, a faint but desperate hope.

“She looks like you,” I said, finding an unexpected smile.

Rahvey took the baby with trembling hands, moving it to her breast. The crying stopped abruptly. My sister tipped her head back a fraction and closed her eyes.

“Three daughters only,” Florihn intoned. “Blessing. Trial. Curse. The fourth is unseemly.”

“Florihn?” Rahvey said, gazing at the infant now.

“Look what you are doing to her!” said Florihn, seizing my arm and turning me round. “You don’t live here, Anglet. You don’t belong here.”

Anger flashed in my eyes, and she let go of my arm as if it were hot, but then her face closed, hardened.

“We will give the child up,” she said. “That is the end of the matter.”

“Florihn?” said Rahvey.

The midwife turned to her reluctantly, her expression softening. “What do you need, hon?” she asked, sugar sweet.

“Maybe,” Rahvey began, like a woman inching out over a narrow bridge, “if we explained to Sinchon and the elders that we could raise her, maybe they would listen.”

“No,” said Florihn, so quick and hard that Rahvey winced, and the midwife had to rebuild her look of simpering benevolence before she could proceed. “I am the elders’ representative here. I speak to and for them. We cannot allow our traditions, the beliefs handed down to us from our grandparents and their parents before them, to be trodden underfoot when they do not suit our wishes.”

“The world changes, Florihn,” I said, amazed at my own audacity. “The things we assume will last forever go away like the Beacon.”

“That is the city,” said Florihn. “That is not us. The Lani must stand by their ways. No mother can have four daughters.”

“Perhaps Vestris would help?” said Rahvey. “She’s rich, connected—”

“Do you see her here?” snapped Florihn. “Your precious sister has not come to see you for how long now?”

Rahvey said nothing.

“You should forget her as she has forgotten you and the place where she grew up,” said Florihn.

I bristled at this, but kept my mouth shut.

Rahvey, meanwhile, seemed to crumple inwardly and, as she began to weep in silence, nodded.

“But she is still your daughter—,” I began.

“The matter is closed,” said Florihn. “I suggest you leave us to our ways, Anglet. You aren’t Lani anymore.”

“What?” I exclaimed. She had said it like it had been on the tip of her tongue for years and she waited for the necessary anger to say it aloud. The accusation awoke a new boldness in me. “Look at me!” I said, sticking out my arms. “Lani through and through. Like the people I have worked with every day since I left the Drowning.”

“Steeplejacks!” Florihn sneered. “What kind of work is that for a Lani?”

“Common,” I replied.

“Urchin work,” she shot back. “City work.”

“Compared to what?” I returned, fury sweeping away my usual diffidence. “Growing a few onions on the edge of a swamp? Mending pots and pans? Peddling folk crafts to people who think they’re quaint? Panning for gold in a river of filth?”

“I will not defend our customs—our heritage—to a … a kolek!”

Even in her rage, she had to steel herself to say the word. A kolek is a type of root vegetable. Its skin is brown, but the flesh within is white.

If she had not been three times my age, I would have hit her.

She saw me flinch, and a flicker of cruel satisfaction went through her face, spurring her on. “But you are not even a kolek,” she said. “If you were, the chalkers would treat you better. You are not one of us. You are not one of them. You are not one of the blacks. You are nothing, and your opinions mean nothing here.”

I reeled as if struck, and the sensation was not just anger and outrage. Her words were a match touched to the powder in my heart, and now it blazed with a hot and poisonous flame: a part of me thought she was right.

There was a long, stunned silence while I gathered my thoughts, and when I spoke, it was quietly and with conviction. “I will take the child,” I said, thinking suddenly and painfully of Berrit, who the world had already forgotten. “She is beautiful. She has been born on the same day Papa was taken from us. She should not grow up unwanted.”

The room fell silent again.

“You?” asked Florihn.

“Yes,” I said, sounding more sure than I felt.

“By yourself? With no husband?” Florihn pressed.

“What use has Sinchon ever been in the raising of your family?” I asked my sister. She looked away. “I will come for her tomorrow, but you can tell the elders that you want to keep her. Make them talk about it. If they won’t change their minds—” I faltered, but only for a second. “—I will keep her. And if I can’t, there is always Pancaris.”

Florihn stared, her mind working, and Rahvey watched her, wary and unsure, like a cornered weancat.

“Tomorrow?” my sister repeated.

“Yes.”

Rahvey looked pale, uncertain, suspended between feelings, but when she felt Florihn’s eyes on her, she nodded.

“This requires a blood oath,” said the midwife, picking up the knife. “You must swear by all we hold true and precious. Hold out your hands.”

I stared at the knife, and the scale of what I was doing crowded in on me so that for a moment I couldn’t breathe. “Not my hands,” I said. “I have to be able to work.”

“Your face, then,” said Florihn, her eyes hard. “There may be scarring.”

I blinked but managed to shake my head fractionally. “It doesn’t matter,” I said.

“Very well,” said the midwife with a tiny, satisfied smile. “Kneel down.”

I did as I was told, feeling the quickening of my heart, as if the blood that was to be let were rising up in protest.

“Anglet Sutonga,” she intoned, “do you swear you will take this child, this fourth daughter, from your sister Rahvey and raise her as your own or, failing that, find suitable accommodation for her, so that she grows up in a manner seemly and fitting for a Lani child?”

I opened my mouth, but the words didn’t come out.

Florihn’s eyes narrowed. “You have to say it,” she said.

“Yes,” I managed. “I swear.”

And without further warning, Florihn slashed my cheeks with her knife, first the left, then the right.

The edge was scalpel sharp, and I felt the blood run before the pain sang out, bright and hot. With it came shock and a sudden terrible clarity.

What have I done?

Florihn methodically took up one of the towels she had brought and clamped it to my bleeding face, gripping my head tightly and staring searchingly into my eyes for a long minute.

There was a knock at the door.

“Can I come in?”

Sinchon.

“In a moment, sweet,” said Rahvey.

“Just tell me,” he demanded. “Boy or girl?”

The three of us exchanged bleak and knowing looks.

“A girl,” Rahvey answered heavily. “We will keep her for tonight, but Anglet will come for her tomorrow. I’m sorry.”

Sinchon said nothing—expressed no sorrow, no commiseration with his grief-stricken wife, nothing—and moments later, we heard the outside door of the hut slam closed as he left.

Florihn was still clamping the towel to my face, pressing hard to stanch the bleeding, and I felt a flare of rage that, for the moment, burned away any doubt that what I was doing was right.

Copyright © 2016 by A.J. Hartley

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window