opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

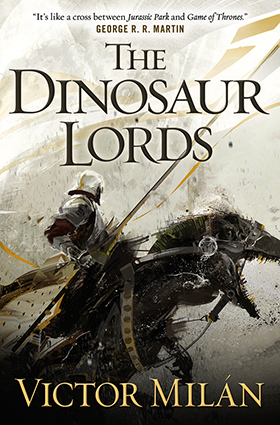

opens in a new window Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Dinosaur Lords by Victor Milán, an epic fantasy set on a distant world when humans live side by side with dinosaurs – and ride them into battle. The final book in the series, The Dinosaur Princess, will be available August 15th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Dinosaur Lords by Victor Milán, an epic fantasy set on a distant world when humans live side by side with dinosaurs – and ride them into battle. The final book in the series, The Dinosaur Princess, will be available August 15th.

A world made by the Eight Creators on which to play out their games of passion and power, Paradise is a sprawling, diverse, often brutal place. Men and women live on Paradise as do dogs, cats, ferrets, goats, and horses. But dinosaurs predominate: wildlife, monsters, beasts of burden–and of war. Colossal plant-eaters like Brachiosaurus; terrifying meat-eaters like Allosaurus, and the most feared of all, Tyrannosaurus rex. Giant lizards swim warm seas. Birds (some with teeth) share the sky with flying reptiles that range in size from bat-sized insectivores to majestic and deadly Dragons.

Thus we are plunged into Victor Milán’s splendidly weird world of The Dinosaur Lords, a place that for all purposes mirrors 14th century Europe with its dynastic rivalries, religious wars, and byzantine politics…except the weapons of choice are dinosaurs. Where vast armies of dinosaur-mounted knights engage in battle. During the course of one of these epic battles, the enigmatic mercenary Dinosaur Lord Karyl Bogomirsky is defeated through betrayal and left for dead. He wakes, naked, wounded, partially amnesiac–and hunted. And embarks upon a journey that will shake his world.

Prologue

Pastoral/Aparecimiento

(Pastorale/Emergence)

Dragón, Dragon—Azhdarchid. The family to which the largest of the furred, flying reptiles called fliers or pterosaurs belong; wingspan 11 meters, stands over 5 meters high. Lands to prey on smaller dinosaurs and occasionally humans. —THE BOOK OF TRUE NAMES

THE EMPIRE OF NUEVAROPA, FRANCIA, DUCHY OF HAUT-PAYS, COUNTY PROVIDENCE

Toothed beaks sunk in low green and purple vegetation, the herd of plump, brown, four-legged dinosaurs grazed placidly, oblivious to the death that kited beside sheer white cliffs high above.

Though he lay on a limestone slab with hands laced behind his head, their herd-boy was less complacent. He had put aside his broad straw hat and green feather sun-yoke, intending to doze away the morning. His small Blue Herder dog, lying in the grass beside him, would alert him if danger from the ground threatened the three dozen fatties in his charge. But then he spotted the dark form wheeling hopefully against the perpetual daytime overcast, and all hope of relaxation fled.

He didn’t believe stories about monstrous flying reptiles like this great-crested dragon swooping down on short-furred ten-meter wings to carry off beasts or men. Nobody he knew had seen any such thing. What dragons could do was land and, tall as houses, stalk prey on wing-knuckles and short hind legs.

I’m not scared, the boy told himself. It was mostly even true. Like land-bound predators from little vexers to Nuevaropa’s greatest predator, the matador, a dragon preferred easy meat. It wouldn’t like stones cast from the boy’s sling, nor the yapping and nipping of a dog far too clever and nimble for it to stab with its sword beak.

The dog hopped up and began to bark excitedly. The boy sat up, feeling bouncer-bumps rise on his bare arms. That meant danger closer to hand.

He sat up to look for it. It wasn’t lurking in the meadow splashed with blue and white wildflowers. That didn’t offer enough cover even for a notoriously stealthy matador.

To his right rose the white cliffs, and beyond them the Shield Mountains, distance-blued, a few higher peaks silver-capped in snow despite the advent of spring. Away to the southwest the land shrugged brush-dotted foothills, then sloped and smoothed away into the fertile green plains of his home county of Providence, interrupted by the darker greens of forested ridges and stream-courses.

Several fatties, still munching, raised frilled heads to peer in the same direction the dog did. Though members of the mighty hornface tribe of dinosaurs, they lacked horns, and might. Meek, dumpy beasts, they grew to the length of a tall man and the height of a tall dog.

They were staring at a dozen or so plate-back dinosaurs that swayed into view in the meadow not forty meters downslope. The beasts’ bodies looked like capital Ds lying down. The herd bull was especially impressive, four meters tall to the tips of the double row of yellow spade-shaped plates that topped his high-arched back, his scaled hide shading from russet sides to yellow belly.

His tail spikes, nearly as long as the herd-boy was tall, could tear the guts out of a king tyrant. The fatties began switching their thick tails, spilling half-ground greenery from their beaks to bleat distress. Plate-backs were placid, but also nearsighted. They tended to lash out with their tails at anything that startled them. Which meant almost anything that got close to them.

The herd-boy was on his feet, dancing from foot to foot, sandals flapping against his soles. His best course was to stay put and hope the intruders went away on their own. If they didn’t, he’d have to chuck rocks at them with his sling. If that didn’t work, he’d be forced to run at them hollering and waving his arms. He really didn’t want to do that.

He looked urgently around for some alternative. And so he saw something far worse than a herd of lumbering Stegosaurus. His dog began to growl.

It strode from the cliff fully formed, Emerging from white stone in one great stride. Two and a half meters tall it loomed, gaunt past the point of emaciation, grey. It lacked skin; its flesh appeared to have dried, cracked, and eroded like the High Ovdan badlands the caravanners described.

He knew it, though he had never seen one. No one had seen one in living memory. Or so far as anyone knew—because most of those who laid eyes on a Grey Angel, one of the Creators’ seven personal servants and avengers, didn’t live to talk about it.

The Angel stopped. It turned its terrible wasted face directly toward the herd-boy. Eyes like iron marbles nestled deep in the sockets. Their gaze struck him like hammers.

I’m dead, he thought. He fell facedown into pungent weeds at the base of his rock and lay trying to weep without making noise.

Through a drumroll of heartbeats he heard his dog barking furiously by his head, where, both prudent and courageous, she had withdrawn while still shielding her master from the intruder. The acid sound of fatties whining their fear penetrated his whiteout terror and kicked awake the boy’s duty-reflex: My flock! In danger!

Realizing he was somehow not dead—yet—he raised his head. His fatties were loping away down the valley, tails high. Then fear struck through him like an iron stinger dart.

The Angel was looking at him.

“Forget,” the creature said in a dry and whistling voice. “Remember when you are called to do so.”

White light burst behind the boy’s eyes. When it went out, so did he.

He woke to his dog licking his face. Bees buzzed gently amidst the smell of wildflowers. A fern tickled his ear.

What am I doing dozing on the job? he wondered. I’ll get a licking for sure.

Sitting up, he saw with sinking heart that his flock was strewn out downhill across low brush-flecked foothills for a good half kilometer.

For a just a moment his soul and body rang, somehow, as if he stood too close to the great bronze bell in All Creators’ Temple in Providence town when it tolled. He tasted fear like copper on his tongue.

The feeling passed. I must have had a bad dream, he thought.

He stood. Cursing himself for a lazybones, he began trotting down toward his vagrant flock.

He prayed to Mother Maia he could get them rounded up again before anyone noticed. It was his greatest concern in life right now.

Chapter 1

Tricornio, Three-horn, Trike—Triceratops horridus. Largest of the widespread hornface (ceratopsian) family of herbivorous, four-legged dinosaurs with horns, bony neck-frills, and toothed beaks; 10 tonnes, 10 meters long, 3 meters at the shoulder. Non-native to Nuevaropa. Feared for the lethality of their long brow-horns as well as their belligerent eagerness to use them. —THE BOOK OF TRUE NAMES

THE EMPIRE OF NUEVAROPA, ALEMANIA, COUNTY AUGENFELSEN

They appeared across the river like a range of shadow mountains, resolving to terrible solidity through a gauze of early-morning mist and rain. Great horned heads swung side to side. Strapped to their backs behind shieldlike neck-frills swayed wicker fighting-castles filled with archers.

“That tears it!” Rob Korrigan had to shout to be heard, though his companion stood at arm’s length on high ground behind the Hassling’s south bank. Battle raged east along the river for a full kilometer. “Voyvod Karyl’s brought his pet Triceratops to dance with our master the Count.”

Despite the chill rain that streamed down his face and tickled in his short beard, his heart soared. No dinosaur master could help being stirred by sight of these beasts, unique in the Empire of Nuevaropa: the fifty living fortresses of Karyl Bogomirskiy’s notorious White River Legion.

Even if they fought for the enemy.

“Impressive,” the Princes’ Party axeman who stood beside Rob yelled back. Like Rob he worked for the local Count Augenfelsen—“Eye Cliffs” in a decent tongue—who commanded the army’s right wing. “And so what? Our dinosaur knights will put paid to ’em quick enough.”

“Are you out of your tiny mind?” Rob said.

He knew his Alemán was beastly, worse even than his Spañol, the Empire’s common speech. As if he cared. He’d had this job but a handful of months, and suspected it wouldn’t last much longer.

“The Princes’ Party had the war all its own way until the Emperor hired in these Slavos and their trikes,” he said. “Three times the Princes have fought Karyl. Three times they’ve lost. Nobody’s defeated the White River Legion. Ever.”

The air was as thick with the screams of men and monsters, and a clangor like the biggest smithy on the world called Paradise, as it was with rain and the stench of spilled blood and bowels. Rob’s own guts still roiled and his nape prickled from the side effects of a distant terremoto: the war-hadrosaurs’ terrible, inaudible battle cry, pitched too low for the human ear to hear, but potentially as damaging as a body blow from a battering ram.

An Alemán Elector, one of eleven who voted to confirm each new Emperor on the Fangèd Throne, had inconsiderately died without issue or named heir. Against precedent the current Emperor, Felipe, had named a close relative as new Elector, which gave the Fangèd Throne and the Imperial family, the Delgao, unprecedented power. The Princes’ Party, a stew of Alemán magnates with a few Francés ones thrown in for spice, took up arms in opposition.

The upshot of this little squabble was war, currently raging on both banks and hip-deep in a river turning slowly from runoff-brown to red. As usual, masses of infantry strove and swore in the center, while knights riding dinosaurs and armored horses fought on either side. Missile troops and sundry engines were strung along the front, exchanging distant grief.

Rob Korrigan worked for the Princes’ side. That was as much as he knew about the matter, and more than he cared.

“You forget,” the house-soldier shouted. “We outnumber the Impies.”

“Gone are the days, my friend, when all King Johann could throw at us was a gaggle of bickering grandes and a mob of unhappy serfs,” Rob said. “The Empire’s best have come to the party now, not just Karyl’s money-troopers.”

The axeman sneered through his moustache. “Pike-pushers are pike-pushers, no matter how you tart ’em up in browned-iron hats and shirts. Or are you talking about that pack of spoiled pretty boys across the river from us, and their Captain-General, the Emperor’s pet nephew?”

“The Companions are legend,” Rob said. “All Nuevaropa sings of their exploits. And most of all, of their Count Jaume!”

As I should know, he thought, since I’ve made up as many ballads of the Conde dels Flors’ deeds as Karyl’s.

The Augenfelsener ran a thumb inside the springer-leather strap of his helmet where it chafed his chin. “I hear tell they spend their camp time doing art, music, and each other.”

“True enough,” Rob said. “But immaterial.”

“Anyway, there’s just a dozen or two of them, dinosaur knights or not.”

“That’s leaving aside the small matter of five hundred heavy-horse gendarmes who back them up.”

The house-shield waved that away with a scarred and crack-nailed hand.

Standing in formation across the river, the three-horns sent up a peevish, nervous squalling. A rain squall opened to reveal what now stalked out in front of their ranks: terror, long and lean, body held level, whiplike tail swaying to the strides of powerful hind legs. In Rob’s home isles of Anglaterra they called the monster “slayer”; in Spañol, “matador,” which meant the same. In The Book of True Names, they were Allosaurus fragilis. By whatever name, they were terrifying meat-eaters, and delighted in preying on men.

A man rode a saddle strapped to the predator’s shoulders, two and a half meters up. He looked barely larger than a child, and not just in contrast to his mount’s sinuous dark brown and yellow-striped length. For armor he wore only an open-faced morion helmet, a dinosaur-leather jerkin, and thigh-high boots.

Thrusting its head forward, his matador—matadora—roared a challenge at the dinosaur knights and men-at-arms waiting on the southern bank: “Shiraa!”

The axeman cringed and made a sign holy to the Queen Creator. “Mother Maia preserve us!”

Rob mirrored the other’s gesture. Maia wasn’t his patroness. But a man could never be too sure.

“Never doubt the true threat’s not the monster, but the man,” he said. He scratched the back of his own head, where drizzle had inevitably filtered beneath the brim of his slouch hat and begun to trickle down his neck. “Though Shiraa’s no trifle either.”

“Shiraa?”

“The Allosaurus. His mount. It’s her name. Karyl gave it to her when she hatched and saw him first of living creatures in the world, and him a beardless stripling not even twenty and lying broken against the tree where her mother’s tail had knocked him in her dying agony. It’s the only thing she says, still.”

No potential prey could remain indifferent to the nearness of such a monster. That was why even the mighty three-horns muttered nervously, and they were used to her. But the house-shield did rally enough to turn Rob a look of disbelief.

“You know that abomination’s name?” he demanded. “How do you know these things?”

“I’m a dinosaur master,” Rob said smugly. Part of that was false front, to cover instinctive dread of a creature that could bite even his beer-keg body in half with a snap, and part excitement at seeing the fabled creature in the flesh. And not just because meat-eating dinosaurs used as war-mounts were as rare as honest priests. “It’s my business to know. Don’t you? Don’t you ever go to taverns, man? ‘The Ballad of Karyl and Shiraa’ is beloved the length and breadth of Nuevaropa. Not to mention that I wrote it.”

The axeman tossed Shiraa a nervous glance, then glared back at Rob. “Whose side are you on, anyway?”

“Why, money’s,” answered Rob. “The same as you. And Count Eye Cliffs, who pays the both of us.”

The axeman grabbed the short sleeve of the linen blouse Rob wore beneath his jerkin of nosehorn-back hide. Rob scowled at the familiarity and made ready to bat the offending hand away. Then he saw the soldier was goggling and pointing across the river.

“They’re coming!”

Shiraa’s eponymous scream had signaled the advance. The trikes waded into the river like a slow-motion avalanche with horns. Before them sloshed the matadora and Karyl.

From the river’s edge to Rob’s right came a multiple twang and thump. A company of Brabantés crossbowmen, the brave orange and blue of their brigandine armor turned sad and drab by rain, had loosed a volley of quarrels.

Rob shook his head and clucked as the bolts kicked up small spouts a hundred meters short of the White River dinosaurs.

“It’s going to be a long day,” he said. “The kind of day that Mother warned me I’d see Maris’s own plenty of.”

The axeman shook himself. Water flew from his steel cap and leather aventail.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said, all bravado. “Even riding those horned freaks, those Slavo peasant scum can’t withstand real knights. Young Duke Falk’s already chased the Impy knights back up the north bank on our left flank. Soon enough our rabble will overrun their pikes. And there’s our victory, clean across.”

Glaring outrage that the man should forget that both of them were peasant scum, Rob said, “You think shit-foot serf conscripts can defeat the Brown Nodosaurs? Even at a three to one advantage? Man, you’re crazier than if you imagine our fat Count’s duckbills can beat Karyl’s trikes.”

“He never faced us before.”

“You really think that matters, then?”

“Five pesos say I do.”

I thought you’d never say that, Rob thought, smirking into his beard.

Downriver to their right, trumpets squealed, summoning the Count’s dinosaur knights to mount. Which meant they summoned Rob.

He held faint hope his scheme, which to himself he admitted was daft enough on the face of it, would win his employer’s last-minute approval. But of faint hopes was such a life as Rob Korrigan’s made.

A cloud of arrows rose from the three-horns’ fighting-castles, moaning like souls trapped by wiles of the Fae. Voyvod Karyl, that many-faceted madman, had famously commissioned artisans in his Misty March to discover treatments to keep bowstrings taut in rain such as this, and to prevent the wicked-powerful hornbows from the arid Ovdan uplands from splitting and becoming useless.

“Shit!” Rob yelled. He was almost out of time.

A-boil with conflicting emotions, he turned and ran as best a run as his bandy legs could muster. He clung to the haft of Wanda, the bearded axe slung across his back, to keep her from banging into his kidneys.

“You’re on!” he shouted back at the house-shield. “And make it ten, by Maris!”

Arrows stormed down on the mercenary crossbowmen on the Hassling’s southern bank. Men shrieked as steel chisel points pinned soft iron caps to their heads and pierced their coats of cloth and metal plates. Rob saw the sad little splashes the return volley made, still fifty meters shy of the trikes. Recurved White River bows sorely outranged the Princes’ arbalests.

The three-horns’ inexorable approach had unnerved the Brabanters. Shiraa’s roar knotted their nutsacks, if the state of Rob’s own was any guide. Getting shot to shit now, with no chance on Paradise of hitting back, was simply more than flesh could stand.

Throwing away their slow-to-reload weapons, the front ranks whipped ’round and bolted—right into the faces of their comrades behind. Who pushed back.

The four stingers the Count had emplaced in pairs to the mercenaries’ either side might have helped them. The light, wheeled ballistas outranged even barbarian hornbows. Their iron bolts could drop even a ten-tonne Triceratops.

But the engines lay broken and impotent in the shallows with their horsehair cords cut. An Eye Cliffs under-groom who’d watched it all had told Rob how a palmful of Companions had emerged from the river Maia-naked in the gloom before dawn. As he yelled his lungs out to raise the alarm in camp, the knight-monks daggered the engineers and the sentries guarding the stingers as they tried to struggle out of sleep. Then with the axes strapped to their bare backs, they’d had their way with the stingers and dragged the wrecks out into the Hassling with the artillerymen’s own nosehorn teams. Before the dozing Augenfelseners could respond, they dove back in the water, laughing like schoolboys, and swam home, having lost not a man.

The under-groom, who for reward had gotten a clout across the chops for not raising the alarm earlier and louder, had seemed equal parts disgusted and amused by the whole fiasco. To Rob, it was a classic piece of Companion derring-do. In the back of his mind he was already composing a song.

But now he was in among the war-mounts—Rob’s own charges—and needed all his wits about him. He dodged sideways to avoid the sweep of a tall green and white tail, vaulted a still-steaming turd the size of his head, sprinted briefly with a little pirouette at the end to avoid being knocked sprawling by the breastbone of a yellow-streaked purple duckbill that lurched forward as it thrust itself up off its belly.

The last he suspected was no accident. Invaluable as their skilled services were, dinosaur masters were commoners. Nobles who employed them, as the Count did Rob, generally suffered them as necessary evils. Their knights didn’t always appreciate them as more than uppity serfs who wanted knocking down.

Or squashing beneath the feet of a three-tonne monster.

But Rob was born sly. His mother had sold him as a mere tad of fifteen to a one-legged Scocés dinosaur master. If he hadn’t made that up; at this remove he had trouble remembering. He’d been forced to come up wise in the ways of war-duckbills. And their owners.

Men shouted. Hadrosaurs belled or piped, each at ear-crushing volume. Down by the river, the Princes’ luckless arbalesters screamed as White River arrows butchered them.

Uncrushed, Rob reached the high ground where the Count had pitched his pavilion. When the Augenfelsen contingent arrived at yesterday’s dusk, this whole stretch of riverbank was all green grass as tall as Rob’s head. Their monsters had chomped it low and trampled the remnants into the yellow mud.

Rob’s head swam from unfamiliar exertion and the concentrated reek of dinosaur piss and farts. That was familiar, surely, but he wasn’t accustomed to forcibly pumping his head full of it like this.

Hapless arming-squires grunted to boost the Count of the Eye Cliffs’ steel-cased bulk into the saddle. Though the cerulean-dappled scarlet duckbill bull squatted in the muck, it was a nearly two-meter climb.

The Count rode a long-crested sackbut—or Parasaurolophus, as The Book of True Names had it. Like most hadrosaurs, it usually walked on its huge hind legs, and dropped to all fours to gallop. It had a great triangle of a head, with a broad, toothed beak and a backward-arcing tubular crest. The crest gave its voice a range and striking tones like the slide-operated brass musical instrument called a sackbut, thus the name.

With a great groan of effort, the Count flung his leg over. Middle-aged at eighty, his lordship tended to spend far more time straddling a banquet stool than a war-mount. It showed in the way his chins overflowed onto his breast-and-back without apparent intervention of a neck. Unlike their lesser brethren who rode warhorses, dinosaur knights didn’t need to keep themselves in trim. Their real weapon was their mount.

Snorting from both ends, the sackbut heaved himself to his feet. A rain-soaked cloth caparison clung to his sides, molding the pebbly scales beneath. Rob counted it a blessing that clouds and downpour muted both the dinosaur’s hide and the Count’s armor, enameled all over in swirls of blue and gold and green—a pattern that the Anglysh, usually without affection, called “paisley.” Unlike most dinosaur knights, the Count had neither picked nor bred his mount to sport his heraldic colors. They clashed something dreadful.

Rob sucked in a deep breath through his mouth. As dinosaur master it was his job to keep his lord’s monsters fit, trained, and ready for war. But it was also his duty to advise his employer on how best to use his eye-poppingly expensive dinosaurs in battle. Duty to his craft now summoned Rob to do just that, and he wasn’t happy about it.

He’d have been tending the Count’s sackbut this very instant had his employer not curtly ordered Rob and his lowborn dinosaur grooms to clear out and leave final preparations to the squires. In their wisdom, the Creators had seen fit to endow the nobles who ruled Nuevaropa with courage and strength instead of wit. Or even sense.

“My lord!” Rob shouted. He clutched at a stirrup. Then he danced back with a nimbleness that belied his thick body and short legs as the Count slashed at his face with a riding crop.

“Shit-eating peasant! You dare manhandle me?”

“Please, Graf!” Rob shouted, ignoring what he deemed an unproductive question whose answer his employer wouldn’t like anyway. “Let me try my plan while there’s still time.”

“Plan? To rob me and my knights of glory, you mean? I spit on your dishonorable schemes!” And he did. The gob caught Rob full on the cheek. “My knights will scatter these brutes like the overgrown fatties they are.”

“But your splendid dinosaurs, lord!” Rob cried, hopping from foot to foot in agitation. “They’ll impale themselves on those monsters’ horns!”

Slamming shut the visor of his fatty-snout bascinet—which Rob found oddly appropriate—the Count waved a steel gauntlet at his herald, who blew advance on his trumpet. Rob winced. The herald couldn’t hit his notes any better than the Count’s mercenary crossbowmen could hit the White River archers.

Rob sprang back to avoid getting stepped on as the Count spurred his sackbut forward. His knights sent their beasts lurching at a two-legged trot down the gentle slope to the water.

“You’ll just disorder your knights when you ride down your own crossbows, you stupid son of a bitch!” Rob shouted after his employer. Whom he was sure couldn’t actually hear him. Fairly.

We don’t just call them ‘bucketheads,’ he thought, wiping spit and snot from his face, because they go into battle wearing pails.

Despite the urgency drumming his ribs from inside, Rob could only stand and watch the drama play out. Even rain-draggled, the feather crests, banners, and lurid caparisons of fifty dinosaur knights made a brave and gorgeous display.

The mercenary arbalesters had stopped shooting. To Rob their only sensible course now was to run away at speed. He knew, as dinosaur master and minstrel both, how little pay means to those too dead to spend it.

Instead, insanely, the rear ranks now battled outright with their fleeing fellows. The Brabanters were among the Empire’s ethnic odds and sods, swept together into a single Torre Menor, or Lesser Tower, that claimed to serve all their interests. Even at that it was inferior to the other Towers: the great families that ruled Nuevaropa and its five component Kingdoms. The Brabanters made up for insignificance with lapdog pugnacity. Which won them a name as right pricks.

The White River archers had stopped loosing too. Their monsters now stood just out of crossbow range. Evidently Karyl was content to observe events.

These happened quickly. At last the Brabanters got their minds right. They quit fighting each other and, as one, turned tail. To see bearing down on them the whole enormous weight of their own employers’ right wing.

As hadrosaurs squashed the mercenaries into screams and squelches and puffs of condensation, the Legion’s walking forts waded forward again. From their howdahs the hornbowmen and -women released a fresh smoke of arrows.

With a pulsing bass hum, the volley struck the Count’s dinosaur knights. Arrows bounced off knightly plate. But duckbills screamed as missiles stung thick hides. Rob guessed the archers had switched to iron broadhead arrows.

Already slowed by riding down the crossbowmen, the dinosaur knights lost all momentum in a chaos of thrashing tails and rearing bodies. Wounded monsters bugled and fluted, drowning the shrieks of riders pitched from saddles and smashed underfoot.

Rob held up his right fist to salute the Count, a single digit upraised. It was, he told himself, an ancient sign, and holy to his patron goddess, Maris, after all.

Then he turned and scuttled east. His employer was a spent quarrel. Now he’d carry out his plan himself.

Chapter 2

Morión, Morion—Corythosaurus casuarius. A high-backed hadrosaur; 9 meters long, 3 meters high at shoulder, 3 tonnes. A favored Nuevaropan war-mount, named for the resemblance between its round crest and that of a morion helmet. —THE BOOK OF TRUE NAMES

Racing across a wasteland of slick, piss-stinking mud proved almost as challenging as evading skittish three-tonne hadrosaurs, if not half so hair-raising. Rob tripped once and slipped once, getting well coated in reeking brown ooze before reaching ground where enough grass survived to stabilize the soil.

Even before he mounted a low hummock to see the log pen he had built to hold his pets, he heard grunts and evil muttering compounded by the odd squeal of annoyance. Upslope by the woods his blue-dappled grey hook-horn, Little Nell, had her snout with its short, thick, forward-curving nasal horn stuck happily in a flowering berry-bush. A stout strider-leather rope secured a hind leg to a tree nearby.

On the palisade perched four local youths. Rain plastered threadbare smocks dyed by the dirt and flora of every place they’d ever been to washboard bodies. They craned frantically up- and downriver in an effort to take in the whole terrific spectacle at once.

Rob had felled the trees for the enclosure in the woods behind the Princes’ camp. His Einiosaurus had dragged them into place. Any dinosaur master worth his silver was a capable jackleg pioneer.

He had built the pen strong. Its two dozen occupants were nearly blind, with brains as weak as their eyes. Like most dinosaurs they wouldn’t customarily challenge a barrier that looked solid. But they might blunder into it.

Renewed trumpeting and banging brought Rob’s head up. The Count’s dinosaur knights finally blundered through into the river, raising big rust-shot wakes. They left most of the Brabanter mercenaries and half a dozen knights on the bank as reddish highlights in mud and the odd steel crumple.

Duckbills stampeded by White River arrows had smashed through the Eye Cliffs riders like boulders tossed by improbably vast trebuchets. Instead of a solid mass the dinosaurry were a straggling herd. But still that invincible buckethead aggression carried the survivors forward.

Straight onto the horns of Karyl’s Triceratops.

Splendid morions and gaudy sackbuts shrieked agony as file-sharpened steel horn-caps impaled chests and throats. Some hadrosaurs reared away from the awful spikes, only to have unarmored bellies ripped open. Never shy about fighting, the trikes put their gigantic heads down to gore and toss with savage joy. Stricken hadrosaurs fell squealing, raising splashes higher than the fighting-castles strapped to their destroyers’ backs.

Meanwhile the archers in those lath and wicker howdahs, hung with slabs of nosehorn hide for armor, kept up their high-intensity arrow storm. At this range the missiles penetrated even plate.

Hornbowmen and -women aimed for helmet eye-slits and the weak points at joints. Some took up lances as targets offered to the sides where their mounts couldn’t engage. The Struthio Lancers, mercenary skirmishers mounted on lithe striders, swarmed around the Princes’ Party flanks, stinging like hornface-flies with arrows, darts, and javelins.

Voyvod Karyl rode his terrible mount in among the foe. Rob saw Shiraa rip an armored sword arm right off a knight, and toss it away like a dog playing with a bone. Karyl’s arming-sword flickered like silver flame. Where it struck, nobles fell.

Rob shook his head. Rain and mud flew from his hair. “I told you so, you great git,” he muttered to his employer. Who was too far to hear, not to mention preoccupied. And wouldn’t have listened anyway.

Rob now found himself facing the dinosaur master’s classic dilemma: above all things he loved dinosaurs, the greatest and most majestic of all the Creators’ works. Yet it was his fate to set them to destroy each other. As always when watching a battle he had helped to make, Rob Korrigan both exulted and despaired.

Worse—far worse—was soon to come. He knew because he would bring it.

Running a hand over his face to clear his eyes of muck, Rob turned and yelled for his helpers to fetch the reed torches he’d laid by in tarred, covered baskets to keep dry, and the cheap tin horns he’d bought from a camp-following sutler’s cart.

“My turn, laddy bucks,” he said.

“Do you really find it beautiful, Jaumet?” Pere asked. His slight build showed despite full white-enameled plate armor. His eyes were large and dark in a gamin face, the lashes long. He wore his jet-black hair shorter than his captain’s, finger-length. Rain stuck it fetchingly to his forehead.

Jaume Llobregat, Count of the Flowers and Captain-General of the Order of the Companions of Our Lady of the Mirror, raised his face to the warm rain. He ran both hands up his face and back through his orange, shoulder-length hair. He relished it all—the feel of skin on skin, the sodden hair’s texture and the flow of water through it. Even the smells of a score of nervous hadrosaurs: all.

Sensuousness was, for him, religious duty.

He sighed.

“I really do,” he said. Standing apart from the other Companions and their giant mounts mustered halfway down the face of the ridge called Gunters Moll, the pair spoke català, the language of their homeland. “The Lady Bella forgive me, I do. We all know how ugly war is up close. But at this remove”—he gestured at the abattoir river—“yes. A terrible beauty. But beauty withal.”

Pere shook his head. “You’re better at finding beauty amidst ugliness than I.”

Though Pere carefully tried to keep his inflection conversational, Jaume heard the sullen undertone. They had grown up together, best friends long before they became lovers.

He smiled, hoping to lighten Pere’s mood. “Perhaps. After all, isn’t life always a matter of picking out the beautiful from the hideous?”

“If only all things were beautiful,” Pere said.

“What then, dear friend? We strive to increase beauty in this world of ours. But we’ll never eliminate the ugly. Should we even hope to? You’re a master painter. Isn’t the figure meaningless without ground? Without ugliness for contrast, how can we perceive beauty? Isn’t it ugliness that gives beauty meaning?”

Pere gave his head a peevish little shake. “You’re always right.”

Jaume put a hand on the pauldron that protected his friend’s left shoulder, enjoying the feel of curved steel and the raindrops beading on its smooth surface.

“Don’t I wish that were true? And anyway, when I’m lucky enough to be right, it doesn’t mean you’re wrong, does it?”

Pere looked away. He always brooded before combat. He had no taste for battle. He was merely very good at it.

But Jaume knew something more was undermining his friend’s composure.

“How I love this rain!” a sardonic voice called from behind. He turned to see Mor Florian approaching, looking only slightly awkward as he negotiated the slanting mud and wet grass-covered slope in his metal shoes, or sabatons. His blond hair, normally kinked, hung like a wet banner past his shoulders.

“How can you like this rain?” demanded red-haired Manfredo, who stood nearby talking with his lover, Mor Fernão. A former law student from far Talia in the Basileia of Trebizon, Manfredo loved Order as much as Beauty. As such he mistrusted Florian, who seemed to him to represent its opposite.

Florian grinned. “Consider the alternative: boiling alive in our portable steel ovens.”

The others laughed. Even Pere relaxed. His hand at last sought Jaume’s and was happily received. Although delicate in appearance, it had the strength of steel wire, and the telltale calluses left by the tools of his three excellences: brush, guitarra, and the blade.

I know what troubles you, old friend, Jaume thought. You dread our return to the Imperial Court at La Merced. But if Uncle accepts my suit, and I marry my Melodía, things needn’t change between us.

He shook his head. That was fatuous. The problem wasn’t with the Princesa Imperial, his other best friend and lover—quick-witted and spirited, with her cinnamon skin and laughing dark-hazel eyes and wine-red hair.

Jealousy was considered a vice on Nuevaropa, particularly in the cosmopolitan South. But it had always gnawed Pere. Now it threatened to consume their friendship.

“Dispatch for my lord Count Jaume!”

Down the flank of Gunters Moll, past the plate-and-chain-armored ranks of Brother-Ordinary men-at-arms standing by their coursers, rode a young page in von Rundstedt livery. His blue-feathered great strider seemed to fly across slick grass.

“Give way! I bring a change in plans to the worshipful Captain-General!”

“It’s time,” said Jaume. “Bartomeu, if you please?”

He walked toward his own mount, the beautiful white and butterscotch morion Camellia. She stood tipped forward onto her forelimbs, plucking daintily at weeds with her narrow muzzle. Hers was an oddly graceful breed, despite the way their low-set necks emphasized their bodies’ bulk. She had carried Jaume through many desperate adventures; he loved her like a daughter.

Blond Bartomeu, his arming-squire, trotted up to strap Jaume’s bevor shut at the nape of his neck to protect his lower face and throat. Then he urged Camellia to her belly with soft words and pressure on her reins to allow Jaume to mount.

“What could this mean, Jaumet?” asked Pere as his own arming-squire brought his strikingly patterned white-on-black sackbut Teodora to the ground.

“A change of battle plan?” said Florian. “How? It seems pretty straightforward: wait until the White River three-horns break the Princes’ knights, then chase the survivors into the hills. Easy, thank the Lady. What’s there to change?”

“Whatever our marshal commands, we must obey,” intoned Manfredo. His beauty was marred by a somewhat over-square chin, and a tendency to sententiousness.

The strider’s long-toed hind feet scrabbled to a halt near Jaume. Its young rider, with blue eyes and a peaches-and-cream Northern complexion beneath near-white hair, simpered at Jaume as he handed over a wax-sealed scroll.

“If you think you’re going to seduce your way into the Companions,” Florian called, “think again.” The boy blushed furiously.

“Florian, be kind,” said Jaume. “Well done, lad. Thank you.”

The courier stammered thanks and rode back uphill as fast as his steed’s two strong legs could carry him. Jaume frowned at the Imperial commander Prinz-Marschall Eugen’s signet stamped into indigo wax. He wondered the same thing as Florian. With a curious apprehension creeping up his neck and into his cheeks he broke the seal, unrolled the scroll, and read.

A chill swept over him like the winter wind that blew down from the Shields into his homeland. He read the few lines of obsessively neat penmanship three times over, blinking at the rain. The letters did not rearrange themselves into a more pleasing order.

Crumpling the parchment, he threw it to the ground. He felt startled gazes. It was an uncharacteristic gesture.

“What is it?” Pere cried.

Not trusting himself to speak, Jaume turned and vaulted into Camellia’s saddle. Clucking gently, he got her to her feet. She raised her head with its great round orange-dappled crest and sniffed the air eagerly. Like any good war-hadrosaur, Camellia welcomed battle.

Jaume leaned down to accept his sweep-tailed sallet helmet from Bartomeu. A page stood by holding Jaume’s shield and lance. He took them.

Cradling his helmet in the crook of his arm, he faced his knights. So few, so brave, so beautiful, he thought. They were only sixteen, out of the twenty-four their Church charter allowed his order. So many more Companions than that had passed through their ranks, to invalid retirement or the Wheel’s next turn.

Who’ll join them today? he wondered. If it’s my time to be reunited with my Lady, I won’t regret it. I have lived my life in beauty.

“Brothers,” he called, pitching his voice to carry. “Whatever I do, follow my lead.”

The others stared. “What else would we do?” Florian asked in disbelief.

Jaume shook his head. “I’ve never asked you to perform such a mission before. And I pray our Lady, never again!”

“Come on, girl! That’s the way!”

Whacking Little Nell’s flank with a willow withe—which didn’t hurt her; that would’ve taken an axe handle, or better, an axe—Rob drove the two-tonne hook-horn into the river. The chains he’d yoked her with clattered taut. With a groan the wall section tipped outward, then fell with a splash and a slam.

The penned dinosaurs raised bleats of alarmed annoyance. Moving up to grasp the halter strapped to Nell’s snout behind the horn, Rob led her far enough upstream to clear the logs from the opening. Then he unhooked the chains and let them fall into the water.

He slapped the hook-horn’s broad fanny. Snorting and tossing her head, she trotted twenty meters, splashing maroon water, then turned and hightailed it up the bank. She would wander into the woods a short ways and graze; Rob knew his beloved mount well.

“All right!” he yelled to his young helpers. “Chase ’em out!”

On the inland wall, the four Eye Cliffs youths blew enthusiastically on toy horns and waved torches that popped and smoked and sparked in the now-sparse rain. Despite the circumstances, the discord made Rob wince.

Can’t the little blighters try to find the pitch, even on such lousy instruments? But now was no time to play the artiste. He pulled a tin horn from his belt and blew it as thoughtlessly as they.

The herd of wild lesser mace-tails he’d spent the past week catching and gingerly herding along behind the Princes’ army streamed out the gate. The Book of True Names dubbed them Pinacosaurus. A smallish breed of ankylosaur, no more than five meters long, with rounded bony-armored backs as high as Rob’s shoulder, they carried really terrifying two-lobed bone maces at the tips of their tails.

Which they swung ominously from side to side. The brutes were well and truly pissed. In that state their first reaction was to smash something. Also their second and third.

Above all, the mace-tails feared two things: fire and noise. By means of both, the urchins drove them into the river. Rob hoped his terrible tootling, plus the keen sense of when to jump and which way that was a vital part of any dinosaur master’s repertoire, would keep the monsters from venting their rage on him.

Blunt armored heads held low, the mace-tails churned across the Hassling. Hoping the youths would remember what he’d told them to do—and actually do it—Rob ran alongside the herd, honking like a mad thing.

A cry of many voices but one single note—droning despair—rose from the Princes’ left. Men-at-arms, dismounted and helmetless, sloshed up the near bank. On a silken banner stretched between them, its once-glorious colors smirched unrecognizably, they carried the limp form of the Count.

The black shaft, fletched with the White River Legion’s two grey feathers and one white, jutting from the right eye-slit of his bascinet told all.

The handful of rebel dinosaur knights who had survived the three-horns were in full retreat. A hundred meters from the river, a thousand men-at-arms sat warhorses that fidgeted and rolled their eyes as the musically bellowing monsters stampeded past to the west of them. Poised to chase and butcher foes fleeing the Count’s war-hadrosaurs, they now found themselves facing the full jubilant wrath of the White River Legion trikes.

Karyl rode Shiraa along the front rank, reordering the monsters into a compact horn-bristling bloc. Though some of the fighting-castles had lost crewfolk, so far as Rob could see not a single three-horn had fallen.

Legion trumpets blew. The Triceratops came inexorably on again.

The mace-tails were loping now, breaking water powerfully if not fast. Rob and his yokel helpers stopped knee-deep in water to watch. They didn’t want to be close to what was about to happen.

Colossal three-horned heads tossed and bellowed. The trikes’ eyesight wasn’t keen. But they smelled ancient enemies. And the mace-tails smelled them.

Paranoid, bellicose, rivals for the same graze, mace-tails and three-horns were uniquely suited to do each other harm. Trikes could flip the low-slung monsters on their backs with their horns to gash open tender bellies. But in close, the ankylosaurs could smash Triceratops knees with their eponymous tail-clubs. They could even scuttle under a three-horn to bash the vulnerable insides of its legs.

These things began to happen. In an eyeblink the Legion’s iron discipline shattered. Eyes rolling in terror, Triceratops bolted from those terrible tails. Fighting-castles broke away from tall backs to topple into the water, carrying passengers to mostly horrible fates.

Laughing and weeping, Rob Korrigan danced in bloody water. What he felt was beyond even his jongleur’s tongue to describe.

He despised all nobles with a fine lack of discrimination. With one exception: Voyvod Karyl Bogomirskiy, the lord who was his own dinosaur master, the age’s unequaled artist in the use of dinosaurs in war. The hero who had fulfilled his legendary quest.

Now, with one frightful stratagem, Rob was bringing down Karyl’s invincible White River Legion. And crippling and killing the things Rob loved most on Paradise. It was triumph and profanation all in one.

“What are you waiting for, you tin-plated cowards!” he shouted at the immobile ranks of Princes’ Party cavalry, who assuredly couldn’t hear him. “I’ve given you victory on a golden plate. Take it! Take it, and eat, damn you!”

Choking on sobs, he fell to his knees. Snot streamed from his nostrils.

To his right the fighting had died down. Rob saw the Princes’ peasant infantry flowing back south out of the Hassling, but without a rout’s mad urgency. The Brown Nodosaur ranks inexplicably continued to stand on the northern bank, wall-solid behind a berm of corpses. They showed no signs of indulging in their customary pursuit plus slaughter.

Down the now-clear river rode several score dinosaur knights. Rob blinked in amazement. Leading them came the Princes’ Party hotspur, young Duke Falk von Hornberg. His mount, Snowflake, was the most dreaded flesh-eating dinosaur in all of Aphrodite Terra, a king tyrant—Tyrannosaurus rex, an import to Nuevaropa. An albino, Snowflake was small for his race, no longer than Shiraa, though burlier. Whether dwarf or merely adolescent, Rob didn’t know.

Waving above the hadrosaurs that trudged nervously behind the big white meat-eater, Imperial banners mingled implausibly with those of the rebel Princes.

“What in the name of the Fae is going on here?” Rob demanded. He sat back on his heels in the bottom muck to watch.

From the north bank pealed a mighty fanfare. White-enameled armor gleaming even in the paltry sun, the Companions trotted to the aid of Karyl’s Legion. That roused Rob’s soul: if he could admire another noble than Karyl, it was Count Jaume.

Of course, that intervention by a handful of dinosaur knights, with five hundred heavy horse behind, could spoil the grand and perfidious success of Rob’s scheme. But he’d shot his bolt. Now he prepared to watch events unfold with a connoisseur’s eye—and happy anticipation of the clink of silver in his cup from the songs he’d sing about this.

Jaume, his face obscured by sallet and bevor but whose famous mount, Camellia, was unmistakable, couched his lance and charged. After what seemed a moment’s hesitation, his Companions did likewise. As one, their hadrosaurs opened their beaks to bellow.

No sound came out—that any human could hear. Rob rocked back with eyes slamming shut as the terremoto’s side blast struck him like an unseen fist.

When he opened them again, he refused at first to believe them.

It wasn’t the approaching dinosaur knights reeling and clutching heads streaming blood from ruptured orifices. It was Karyl’s fighting-castle crews.

Armored from the front against the hadrosaurs’ silent war cry by bony frills and faces, almost all the three-horns had their backs to the Companions. They too suffered the terremoto’s full effects: fear, burst eardrums, even lesions in the lungs. A Triceratops bull reared high, pawing the air and bleating like a gut-speared springer. Its howdah broke loose, spilling men and women flailing into the river.

The Companions charged straight over them.

Rob boiled to his feet. “What’s this?” he screamed. “Treachery?” He hardly knew what else to call it.

The surprise attack caught the already-disordered mercenaries utterly helpless. Even though by now the mace-tails had bulled their way clear to scramble up the north bank and make for the woods, the Legion stood no chance. Formidable as Triceratops’ horns were, they were effective only against an enemy in front of them. Even the Companions’ Ordinaries worked wicked execution, their horses looking like toys as they hamstrung horned colossi with sword and axe.

Karyl rode Shiraa at a spraddling, splashing run, trying desperately to herd his surviving three-horns west. That way offered their sole hope of escape.

His matadora came flank to flank with a Companion halberd. The white-and-green brindled hadrosaur was bigger; Shiraa had teeth. Though his eyes rolled in fear beneath a crest with rounded blade to the front and a spike angled to the rear, the Lambeosaurus bull didn’t give way. The Companions trained their mounts to overcome even their marrow terror of big meat-eaters. Indeed, the halberd could easily knock the war-galley-slim Shiraa down.

But Karyl’s blade slid unerringly through the eye-slit of the Companion’s close helmet. The white knight fell. His mount fled, trumpeting despair.

Falk and Snowflake fell on the mercenary lord from his blind spot. For Rob it was a surfeit of wonder: since carnivorous war-mounts were so rare, they almost never faced each other in battle.

Somehow sensing danger, Karyl wheeled Shiraa clockwise. Snowflake struck first. His huge jaws tore a strip of flesh from Shiraa’s right shoulder.

The matadora screamed. Her raw wound steamed in the rain, which had begun to come down heavily again.

Falk’s battle-axe swung down to smash in the crested crown of Karyl’s helmet. Rag-limp, Karyl Bogomirskiy fell into the rising, frothing torrent and vanished.

For a moment Rob thought Shiraa would stand above her master. She and Snowflake darted fanged mouths at each other, roaring rage.

Dinosaur knights, Princely and Imperial alike, closed in. Reluctantly Shiraa backed away. With a sorrowing wail she turned and fled downstream.

The rain closed in, obscuring Rob’s sight. Or was it tears?

Rob Korrigan rocked on his knees in the unforgiving river. He mourned beautiful and mighty beasts, and greatness’s fall. And cursed himself for the part he’d played in all.

“What have I done?” he sobbed. “What have I sold?

He raised fists to a leaden Heaven. “And what has it bought me?”

Chapter 3

Horror, Chaser—Deinonychus antirrhopus. Nuevaropa’s largest pack-hunting raptor; 3 meters, 70 kilograms. Plumage distinguishes different breeds: scarlet, blue, green, and similar horrors. Smart and wicked, as favored as domestic beasts for hunting and war as wild ones are feared. Some say a Deinonychus pack is deadlier than a full-grown Allosaurus. —THE BOOK OF TRUE NAMES

The first thing he knew was pain.

Agony beat from his left hand like the pounding of a drum. Blind, he pulled. A cold, rubbery grip resisted.

He became aware of a chill enveloping his whole being, which leached away whatever strength remained within him. A stench, vast as a slow sea surge, of decay. A more concentrated stink, like wind-driven chop, of filth and feces and stale grease.

Cadenced grunting, as of effort. The pain resolved to the root of his finger.

Last came light on sealed lids, red through. He tried to open his eyes. They refused. The pain in his hand came rhythmic, insistent. His head hurt.

Still without knowing who did so, he willed his eyes to open. Hard. Eyelids parted with a tearing like a wound reopened. He realized dried blood had stuck them together. A crumb caught in the lower lid rasped his left eyeball.

The clouds hung darker and lower than usual. He lay among reeds, half-submerged in cool water. Indistinct against slate sky, a haggard, filthy figure squatted in the river, sawing at his ring finger with a knife. Its blade was apparently none too keen.

He tried to pull his hand away. Squalling like a vexer, the looter yanked back. Dark eyes widened in fury and alarm behind kelp-streamer hair. The knife flashed toward his face.

He fell onto his back in the water, still joined to the looter by his wrist. He put his right hand down to brace. His fingers encountered something hard, cruciform. Before he consciously knew it was a sword hilt, he had it grasped and was lashing back.

Impact shivered up his arm. Blood slashed his face in a hot, hard spray. The looter screeched again and fell back, thrashing and splashing green water that gradually turned the color of rust.

Absently the man wiped at nose and cheeks, discovering in the process a stubble of beard. It felt unfamiliar.

The looter’s sloshing subsided. The man glanced down at the sword in his hand and grunted. The blade was snapped off half a meter from its ornate hilt. It had sufficed.

Now still, the looter’s body floated on its back with arms extended and forehead tipped back in the water, surrounded by hair like a water-weed halo. From the long skinny breasts tied across its belly with a rawhide thong the man realized he had killed an old woman.

The knowledge evoked little response, beyond detestation for those who preyed on the helpless. Nuevaropa abounded so fantastically in plant and animal life that starving took effort. To be sure, foraging had its risks—like everything else. But no hunger of the belly had driven this creature to attempt to mutilate him. Or kill him when he had the temerity to wake.

That she looked old struck him strange. He did not know why.

He examined his wounded hand. His third finger bore a heavy gold ring that showed a three-horn’s head in bold relief. A line of blood encircled its base. Looking closer he realized the wound was shallow but ragged. As he’d suspected, the looter’s knife was blunt.

Likely she had a bag of small stolen treasures, now sunk with her in shallow water. That brought complete indifference. He was beyond any desire for gold now.

Survival was another matter. Maybe. He felt vague stirrings of alarm.

The ache throbbing in his head was even more persistent and powerful than that in his hand. He reached up gingerly.

Fingertips found close-cropped hair. The right side of his skull felt moist, mushy; he wondered if it might actually be dented. The pain that shot behind his eyes clear down to his stomach didn’t encourage him to probe further.

He felt his first stab of true emotion: dread that he might feel the exposed surface of his brain.

He knew where he was, in general. He remembered facts about his surroundings, the natural world, the structure and functions of his body. And how to wield a sword, clearly, natural as breathing; he transferred it to his left hand without conscious thought. But what he was doing here, naked in the shallows of a broad river beneath storm-threatening skies, was a mystery to him.

So was just exactly who he might be.

Urgency began to churn his belly. Life wasn’t exactly proving attractive, now he’d been restored to it. But the animal within, once wakened, desired desperately to cling to it.

He rose from the water. Unsteady on quivering blue-white legs, he looked around. The world resolved about him as though summoned into being by the act of observation: a riverbank fenced with a green riot of weeds. The mud beyond, churned by the feet of many men and monstrous beasts. A slope covered in low vegetation climbing to a forest. The air lay cool on his skin.

The stench of rotting flesh was profound.

A tearing noise made him turn, splashing, sword-stub ready. Fifteen meters out in the river and a bit downstream lay a dead duckbill. In the wet warmth the gases of decomposition were already ballooning its vast body. A once-glorious hide of scarlet, orange, and gold had faded to greyish pink, ochre, and mud. A small tailless flier with drab brown fur perched atop it, ripping up a strip of skin with its beak.

Everywhere sprawled or floated the rotting corpses of men, horses, and dinosaurs. Not twenty meters from him a Triceratops lay on its side in mud, its eyes picked empty. Beside it lay a fighting-castle, wickerwork sides and wooden frame broken by the monster’s fall. Inexplicably, the sight of the great dead dinosaur twisted his heart and stung moisture from his eyes.

Who am I, he wondered, to wear a ring worth finishing me off for, and to grieve so for a dinosaur?

It scarcely mattered now. Now he was no one, mother-naked and stinking with a dent in his skull, lost.

It was morning, he observed from the feel and color of the sun’s diffuse light and the way the faint shadows leaned east. Neck muscles creaking and bones crackling protest as if they’d expected never to be used again, he turned to look upstream.

Carnage lay thicker there. Indistinct with distance and mist wisping from the river, men moved about the banks, singly or in small groups. Most were afoot; a few rode horses or striders. He saw no living war-hadrosaurs. Nor any big meat-eaters drawn to the feast.

Oddly, that saddened rather than relieved him.

Fear stabbed him through: I mustn’t be found! he thought.

Whoever he was, he felt a sick certainty that those men would do him harm if they learned he still lived. Painfully he climbed onto land and began to stagger downstream through tatters of mist.

Returning circulation first pricked his legs like needles, then stuck like knives. As he forced himself to a jarring trot, his pulse kept stride. The hammers beating at his temples did likewise.

From thicker fog before him a figure appeared, dark, compact, hooded. He stumbled to a halt, though limbs and body cried out together that once he lost momentum he might never get it back. For three heavy heartbeats, each of which threatened to burst his skull, he stood watching, head tipped to one side, breath wheezing through open mouth.

The figure stood unmoving. Waiting.

What have I left to lose? the man asked himself bitterly. He approached. He couldn’t really walk, but only engage in a more-or-less controlled forward fall.

He knew he wasn’t a large man. The waiting figure was smaller still. Despite the looseness of its coarse brown robe, its carriage told him it was female.

The apparition’s voice confirmed it: “A moment, Voyvod Karyl,” it said, feminine and low.

“Voyvod Karyl,” he repeated slowly. The words seemed to echo through the clangor in his skull.

He touched his head. “He’s dead, I think.”

The cowl nodded. “I know. It’s why I speak to you. I speak only to the dead.”

“You’re … the Witness?” he asked. Childhood stories, half-remembered and less believed, clamored in his memory, like faint contending voices overheard down a long corridor.

“I am. I try to watch all of this world’s great events.”

“And never intervene,” the man said.

He felt no sense of identification with the name she had given him, had scarcely any sense of that man or his past. His memories were too troublesome, too painful, to try to bring into focus.

“Just so,” she said.

“Not possible. The Witness can’t be real. I’ve known of people living as much as three centuries. No longer.”

“The Creators made me different,” she said.

He uttered a corpse-tearer croak. It was as close to a laugh as he could come.

“The Creators don’t exist either. My wounds are making me delirious. Well then, myth. What do you want from me?”

“Knowledge,” she said.

“You must have a surfeit of that. If you’re the Witness, you’re as old as the world.”

He spoke bluntly, for dead men have small need of tact. He recalled that the man he had been spoke little and to the point as well.

“Older,” she said. “Seven centuries isn’t long, for the subject I study. Barely a beginning.”

“What can I teach you?”

“I want to know what it means to be human.”

“Compared to what?”

“Dead or not,” she said, “that I cannot tell you.”

“I am cold and naked,” he said. “My mouth is as parched as the rest of me is soaked. I’d drink, and no doubt I’d be famished, if my stomach weren’t in total rebellion. My head feels ready to split apart. Someone hunts me, I don’t know who. I doubt I’ve time to tell you much.”

“You’ve no time at all, Lord Karyl,” she said. “But each conversation with the doomed, however brief, expands my knowledge.”

“We’re born in pain and trepidation. It seems we die the same way, although for some unfathomable reason I’ve yet to learn for sure. We like to imagine we can live in some different state. Whether that’s illusion, I know no more than you.”

“You’re eloquent for a man in your condition. The tales told of you seem true.”

He waved dismissal with the broken sword. “Whatever they say, they’re all lies now.”

She floated toward him, her legs not stirring the hem of her robe. A white blanket of mist hid her feet. The cowl tilted up toward his face.

Inside he could see nothing but blackness.

“Ah, Karyl Vladevich,” she said. “You have done deeds that shook the Tyrant’s Head, and may yet reverberate across Aphrodite Terra and all the wide world. I had such hopes for you.”

“No doubt I’ve disappointed many people,” he said. “I fear I’ve gotten many killed. I don’t think I want my memories back. Even if you offered me something for sharing them.”

“I can give you nothing. It would disturb Equilibrium.”

“The sacred Order of the World,” he recited like a catechism. It was, he realized. His lips twisted in a savage smile. “We can’t have that.”

She raised sleeve-shrouded arms as if to touch his face. Irrationally he recoiled.

“There’s something about you—” She stopped, shook her head: an oddly peevish gesture for a mythical being. “No. It can’t be. You will soon be dead to stay, and so will end the saga of Karyl of the Misty March.”

It was only then he realized she’d spoken his Slavo all along, not Spañol, his native tongue, though her accent was that of a Rus, rather than his Češi people.

From the thickening mists came a chilling sound: a drawn-out ululation.

“They come with dogs to smell you out, Lord Karyl,” she said. He thought he heard a note of sadness in her voice. Or maybe wistfulness. “And horrors to take you.”

“Who?”

“Your murderers.”

He looked over his shoulder. Panic boiled up inside him as a second hound gave tongue. Beneath it he detected the chirps and snarling of the real killers, the raptor-pack who followed the dogs.

“Now I find that, though I thought my life already forfeit,” he said bitterly, “my body still doesn’t want to let it go. Am I to be spared nothing?”

She said nothing, just slowly backed away.

“Help me.”

She spread sleeves that still hid her hands. “I cannot.”

Left and right he whipped his head, seeking some road to safety. His heart fluttered like a netted bug-chaser. He vibrated with the need to flee. He hated the fear. Yet he couldn’t still it.

He glared at her. “Cannot or will not?”

“They are the same. Good-bye, Lord Karyl. May your death be swift and painless.”

“Doubtful,” he said through peeled-back lips. “Can’t you see the future?”

“If I could, would I have troubled you? Now run, my lord. Or die here. Whatever will ease your final moments, do.”

She turned and glided up the slope to the broadleaf trees thronging the ridgeline that paralleled the river. He knew their tantalizing shelter was a lie: his pursuers would be on him before he could hide among them.

Driven as hard now by defiance as dread, he fled east. He ran without hope, and only pain for a companion. His brain bubbled with images: of childhood, lost friends, long travel in exotic lands.

And war. Always war.

They caught him as he ran out of world.

Two kilometers east of the battlefield the ground simply dropped away. Three hundred sheer meters below, the inland sea called the Tyrant’s Eye lay hidden beneath a rumpled grey-white plain of clouds that seemed to extend from the Cliffs of the Eye.

He mastered the temptation to keep running.

Panting from his flight, sword-stub upraised in his left hand, he turned at bay beside a clump of scrub oak. A whistle caused the pair of grey-brown dogs with wrinkled faces and great dangling dewlaps streaming froth that loped in close pursuit to veer aside. Dark eyes rimmed with scarlet veins burned with resentment at being denied the kill.

But they did as they were trained. The brightly feathered death that ran behind would rend them as eagerly as their prey. When their hunters’ blood blazed with the hot joy of the chase, the raptors could only just be restrained from turning on one another.

Eight green horrors trotted into view on strong hind legs, the big killing-claws on their feet daintily upraised. Deinonychus: the biggest and worst of Nuevaropa’s pack-predators. Thus beloved of the nobility, who kept them to hunt men as well as beasts.

Pampered in some lord’s kennel, the three-meter-long killers had gotten their spring plumage early. Their upper feathers were a brilliant green with yellow highlights, their breasts buff streaked with brown. The crests on their narrow skulls were shiny black, as were brow-stripes above staring yellow eyes. Their muzzles were likewise yellow.

A pair of riders followed the pack. A brown-bearded man whose blue, silver, and black tabard, well freighted with belly, proclaimed him a knight straddled a russet great strider with a dainty white feather ruff and silly yellow plume on its small head. It high-stepped in obvious terror of the hunting-pack.

The other man rode a white mule. Taller and leaner than the knight, he wore a ratty cloth yoke to shade his shoulders, greasy loincloth, and beggar’s buskins. His bare legs and wasteland torso were smeared with grime. Beneath greased-back blond hair his face was round yet sparely fleshed, with a brutal beak of a nose.

As they closed in on their quarry, the horrors slowed and began to hiss and sidle. They were as notorious for their cunning as for their cruelty. The sheer cliff at the man’s back helped him: the monsters couldn’t get behind him.

A horror stepped forward and reared to almost the man’s own height, erecting its crest and spreading feathered forelegs wide. Their undersides were shocking scarlet, loud as the challenge the raptor screamed. Its breath stank of death.

A second horror, circling to the man’s right, sprang for him with talons forward and jaws agape. Undistracted by the first one’s display, he sidestepped and hacked off black-clawed toes with a forehand cut. The return stroke gashed open the shrieking green face as the horror flew past. The blade-stump missed the glaring yellow eye, but flooded it in blood.

The creature put its maimed foot down and collapsed. Squalling, it lashed its long tail so violently that the man had to dodge to avoid being knocked off his feet, and possibly the cliff.

The other raptor pounced. The man flowed to meet the attack. Slipping right he sliced the horror’s throat. With a blood-strangled squawk, it stumbled forward over the edge.

The pack chittered furiously. Two had turned to savage their maimed fellow. Behind them, not ten meters from the hunted man, the beak-nosed man sat applauding sardonically on his mule.

“Well done, Lord Karyl,” he said in Alemán. “You bring your legend to its appropriate end. Too bad no one’ll ever hear the tale of your valiant last stand.”

The four horrors not engaged in murdering their injured pack mate hung back, dancing nervously from foot to yellow foot.

“Karyl’s dead,” the man said. The language came readily enough to his tongue. Its gutturals less so to his raw throat.

“That signet ring on your sword hand suggests otherwise. And like the allegedly late voyvod, you’re left-handed, I see.”

The knight’s livery struck forth sudden memory: a midnight-blue helmet, nodding plumes of black, azure, and white. Beside them a curved axe-blade, fast descending.

Then a flash of light, and nothing.

“So the young Duke of Hornberg wants a trophy?” the fugitive rasped.

“No,” the peasant said. “His mother. Or rather, a token that you’re safely dead. It seems she fears you pose a threat to her ambitions for her baby boy. And perhaps she’s right. She was surely wise to send us to make sure of you; you’re as Creator-lost hard to kill as a handroach.”

“Oh, dear,” the fat knight said, as teeth through feathered throat bit off the injured horror’s cries. “His Grace will be most displeased at losing such prime animals, Bergdahl.”

“His Grace will have to buck up,” the commoner said. “Does he think there’ll be no cost if he wants a man like this dead? Or the Dowager Duchess does. And don’t think she gives a malformed hatchling what finishing off the Voyvod of the Misty March costs her dear son in playmates.”

“I hate to kill a man’s pets,” the man said. “Call them off and come face me yourself, Mor Lard Tub.”

“We have explicit instructions—” the knight gobbled.

“Not even this hedge knight’s that big a fool,” the commoner said. “Kill all you can. More will hatch.”

More pain came, in the form of remembering.

“I’ve died once,” the man said. “I can do it again. If your horrors take me my one regret is not avenging Count Jaume’s treachery.”

“Life’s full of disappointments, my lord,” the peasant said.

Lagging behind his swift-footed pack and mounted betters, a stout, balding huntsman with Duke Falk’s black toothed-falcon insignia painted on his hornface-hide tunic came puffing up. He whipped the two horrors still squabbling over their comrade’s corpse back to duty.

Joined by a third they rushed their prey. Two more swung wide to his left to catch him like a soldier-ant’s pincers.

He charged them. His blade split one’s skull. It grated free to chop almost through the forelimb the second reached with to grab him.

Midleap the horror twisted to snap at him. He dodged. The raptor fell among the three lunging from the right and bowled them into a spitting, tail-whipping tangle.

The man ran right at the two riders. Instead of going for the sword hanging from his baldric, the fat knight froze, bearded chins trembling. The commoner merely laughed as if this were the world’s finest joke, and would only be made sweeter were he cut down by a naked man with a broken sword.

But one pack-hunter had hung back. It leapt. Raptor hit man, chest to chest. Lightly built though it was, the horror was as heavy as he. Its momentum drove him back. He punched at it with both fists, trying to fend off the killing-claws slashing at his exposed belly and genitals.

The creature struck like an adder. Sharp teeth snapped shut on the man’s sword arm just above the wrist, crunching through muscle and bone to meet with a clack. Pain shot through him like lightning.

Still gripping the broken sword, the man’s hand flew as if propelled by a blood-jet to land on bare white soil half a meter from the edge. The voyvod’s signet glinted mockery on a twitching finger.

“Well, that’s more luck than we deserve,” the commoner said.

Clutching his feathered assassin to him with his last hand, the man toppled backward into the void.

Chapter 4

Troodón, Tröodon—Troodon formosus. Pack-predator raptor; 2.5 meters long, 50 kilograms. Sometimes imported to Nuevaropa as pets or hunting beasts. Like ferrets, tröodons are clever, loyal, and given to mischief. Vengeful if abused. —THE BOOK OF TRUE NAMES

THE EMPIRE OF NUEVAROPA, SPAÑA, PRINCIPALITY OF THE TYRANT’S JAW, LA MERCED, PALACE OF THE FIREFLIES

“—y con alma tuya, hermano,” the hooded man replied to a hushed greeting from an acolyte he encountered in the gallery that ran along the north wing of the Palacio de las Luciérnagas.

They went their opposite ways. Morning sunlight shone through piercings in fanciful floral shapes carved in the outer wall. On the practice-ground a story below, the Scarlet Tyrants—Imperial bodyguards—contended with a clatter of wooden swords and shields.

The man in the cowl had no name that mattered. He was consecrated to life as a what, not a who. He wasn’t tall. He wasn’t short. He was neither wide nor narrow. The skin on his hands and within his hood’s recesses was sun-browned olive. His eyebrows were black laced with grey, his eyes dark. He looked like many men in Spaña, the southernmost realm of the Tyrant’s Head.

He wore the brown robe of the Kindred of Torrey, with that Creator’s trigram embroidered in yellow on the breast: a solid line with two broken lines beneath it. The current Emperor was well known for piety far beyond what his office required. Men and women of all sects’ cloth were common here.

Altogether, the hooded friar was as unremarkable as craft could make him.

Leaving the loggia, he passed into cool interior and turned into a stairwell. To his right was a nook on whose back wall was painted a fading, peeling scene of black Lanza, the Creator most identified with war, defeating a swarm of misshapen hada during the High Holy War. It concealed a door that opened only in response to a knowing touch.

The cowled man supplied it. He slipped into a narrow way illuminated only by light that filtered from rooms and corridors to either side through slits made to look like ornamentation or even random cracks in the walls. It was part of a network of secret stairs and passageways meant for trusted servants, discreet errands, and persons of high station on low missions.

The Firefly Palace sprawled across a high headland that protected the southern side of Happy Bay, about which stood, leaned, and occasionally rioted La Merced, the Empire’s richest seaport. Yellow-white limestone walls as high as twenty meters and as thick as ten encompassed a square kilometer inside an approximate pentagon. Within lay yards, stables, shops, and barracks. The Palace proper dominated all: an enormous rambling structure well spiked with towers, and courtyard gardens and pools tucked away within.

By arrangement with its owner, Prince Heriberto, the palace currently housed the widowed Emperor, his two young daughters, and the usual gaggle of courtiers. Emperador Felipe liked his comforts, and equally disliked the intrigues and stuffy self-importance of court and Diet in the Imperial capital of La Majestad. Easygoing La Merced was far more to his liking.

But figurehead that he was, the man who sat the Fangèd Throne still attracted intrigue. Especially one who had roiled the waters of state as vigorously as the placid-seeming Felipe.

The hooded man climbed three dim stories. Though he had never been inside the palace in his life, he knew the way well. Nor had he been to the Principado de la Quijada de Tirán. His real order didn’t even serve the Middle Son.

Under most circumstances, this assignment would have been carried out by someone already within the palace, preferably in the Imperial retinue. But none was available. And this commission was urgent as well as of the highest importance.

He peered into a sunlit room through a reaper-feather hanging to confirm it was vacant, then crossed to a door. He had to take great care: the Emperor’s apartments occupied this floor. If he were spotted here, not even his clerical robes would save him from scrutiny he couldn’t risk. The simple fact that he didn’t belong would not escape the attention of men with gazes as sharp as their spears who guarded the Emperor.

He wasn’t afraid of torture. His death would mean little; when he swore the oaths, he had accepted that he would die serving the Mother. The Brotherhood had blessed him with its confidence to carry out this task. He could endure anything but failure.

He slipped into a corridor with milky morning sunlight streaming through pointed-arched windows at either end. He saw no one, but heard prayers murmured behind closed doors. Incense thickened the air.

Silently he strode down the hallway. Despite fanatical training and years of meditation, his pulse raced. So much lay on this single cast.…

And here. The door.

Inside the room a figure garbed the Father’s grey sat in gloom. His back was to the door, his hood bowed in contemplation.

The intruder slipped his right hand inside his capacious left sleeve. His fingers closed around the cool familiar hardness of his dagger hilt.

Carefully he extended his right foot, laid the whole sandaled sole at once on maroon tiles. He would have sworn he made no sound—he would have staked his life.

The grey hood turned. The man looked upon the visage within.

“Your Radiance!” he exclaimed, but softly, softly. He dropped to his knees. His hand slipped from his sleeve, holding his now-forgotten weapon.

“Forgive me,” he said as the figure rose to towering height and approached. “Forgive me, Radiant One! I didn’t know. How could I know?”

“You are forgiven, my son,” replied a voice soft and dry and grey as ash. Its owner reached for him as if to confer benediction.

Naked and still damp from her afternoon bath, the Imperial Princess Melodía Estrella Delgao Llobregat sat on her stool while her maidservant brushed out her long hair, listening to the deep tones her best friend drew from the springer-gut strings of her vihuela del arco.