opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

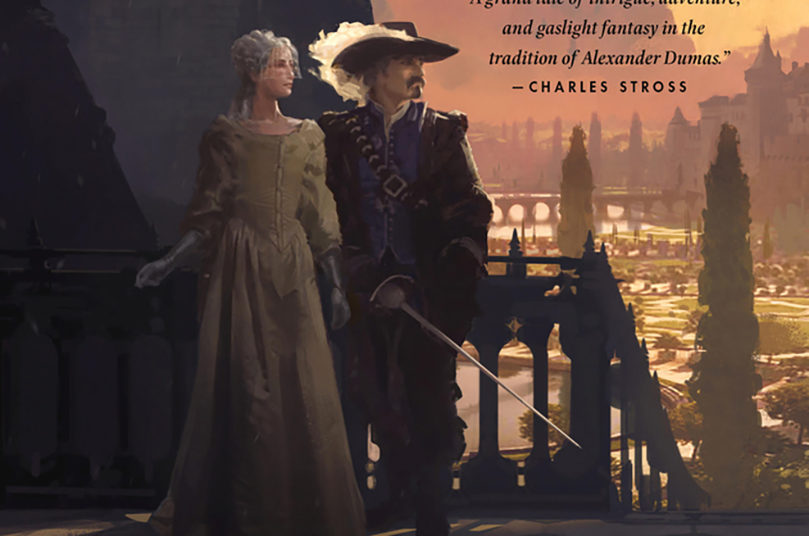

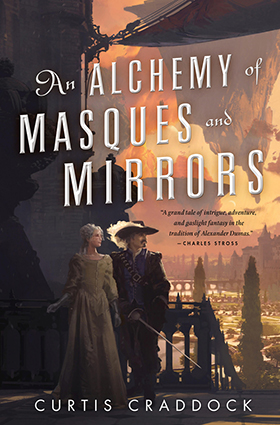

opens in a new window Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an excerpt introducing An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors by Curtis Craddock. This book is the first in a brand new series featuring a princess seeking to keep the peace with only the aid of her wits and her loyal musketeer guardian.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an excerpt introducing An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors by Curtis Craddock. This book is the first in a brand new series featuring a princess seeking to keep the peace with only the aid of her wits and her loyal musketeer guardian.

In a world of soaring continents and bottomless skies, where a burgeoning new science lifts skyships into the cloud-strewn heights, and ancient blood-borne sorceries cling to a fading glory, Princess Isabelle des Zephyrs is about to be married to a man she has barely heard of, the second son of a dying king in an empire collapsing into civil war.

Born without the sorcery that is her birthright but with a perspicacious intellect, Isabelle believes her marriage will stave off disastrous conflict and bring her opportunity and influence. But the last two women betrothed to this prince were murdered, and a sorcerer-assassin is bent on making Isabelle the third. Aided and defended by her loyal musketeer, Jean-Claude, Isabelle plunges into a great maze of prophecy, intrigue, and betrayal, where everyone wears masks of glamour and lies. Step by dangerous step, she unravels the lies of her enemies and discovers a truth more perilous than any deception.

An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors will be available August 29th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Chapter 1

Jean-Claude clung to the St. Marie’s guardrail with one hand and to his tether with the other. He wanted a word with Captain Jerome, who stood on the quarterdeck, an impossible distance away. Unfortunately, doing the impossible was a sworn part of Jean-Claude’s duty, so he slide-stepped awkwardly toward the skyship’s stern as the vessel climbed a tall ridge of turbulence. The whistling wind made jib sails of his tabard’s loose sleeve flaps, tugging him toward the rail and the emptiness beyond.

All around him, deckhands scurried about, tugging on lines, adjusting sails in a madman’s dance choreographed to the boatswain’s cry. Jean-Claude reached the curling stair to the quarterdeck and climbed, stumbling as his leather riding boots slipped on cloud-slicked steps. He achieved the top of the stair just as the St. Marie crested the pressure ridge.

The masts creaked, and the vast spiderweb of rigging hummed with tension as the ship’s enormous stresses shifted. For a moment, Jean-Claude hung weightless, floating free as a smoke puff on the wind. His toes strained to reach the deck beneath his feet but succeeded only in propelling him away from it. The skyship banked, bumping and tilting him halfway over the rail. Beyond that flimsy frontier and far below the turvy sails thrusting down beneath the hull awaited the Gloom, a fathomless abyss of lightning-shot clouds. Those clouds beckoned him like the pillowed embrace of a familiar paramour. Against all good sense, he yearned toward the abyss. His grip on the rail slipped.

Then his own weight landed on him hard. He hit the deck with a knee-popping thump. His boots slipped and he tumbled to his backside. His heart rattled around his ribs like a die in a cup. Carefully, he eased away from the edge of the ship.

He hated skyships. How many men before him had been claimed by the fatal impulse to let go? How many had felt the sick urge to fall forever, down to where the clouds never parted, the rain never ceased, and the wind ripped ships and men to pieces? Every time Jean-Claude saw it, it called to him.

I should have stayed a farmer. If only he had been an obedient lad, dutifully following a plow through rocky fields, he would never have sneaked away from his chores to watch the Duc d’Orange’s forces bring battle to the raiding Mark of Oberholz. Then he would never have chanced upon the wounded duc or hidden him from the mark’s search parties. He would never have earned the duc’s gratitude or been shoehorned into l’École Royale des Spécialistes. He would never have been attached as liaison to the Comte des Zephyrs, and he never would have been ordered to get on one of these hundred-times-damned flying boats.

From the forward rail of the quarterdeck, Captain Jerome watched Jean-Claude’s progress with evident amusement.

“Six weeks aloft and you still haven’t got your sky legs,” Jerome said with an aloof, aristocratic amusement that suggested he’d expected no better. A landless, penniless seventh son of minor clayborn gentry, Jerome treasured the singular noble privilege to which he was entitled: disdain for the lowborn. His sole redeeming feature, in Jean-Claude’s eyes, was that he was good at his job, an asset rather than an impediment to his crew, a circumstance all too rare in the gentry-swollen navy.

Jean-Claude scrambled to his feet and tried to recover poise as well as balance as the skyship accelerated into the next aerial trough.

“You said we were about to make land!” His own privilege, as King’s Own Musketeer, was deferring to no one outside his own very short chain of command. Of course, keeping that privilege meant completing his missions without falter or fail, no matter the distance or danger. Orders like “Deliver this message from my lips to the comtesse’s ears ere the baby is born” did not account for time spent evading pirates or allow for being blown a week off course by an unanticipated aetherstorm.

Jerome stood on the rolling deck as if nailed to it, not a hair of his white powdered wig out of place. He jerked his chin toward the bow and said, “We’re coming in widdershins on the trailing edge,” as if that clarified the matter. “If we don’t undershoot and ram the light tower, we should make harbor within the hour.”

Jean-Claude turned. With the St. Marie on a decline, l’Île des Zephyrs rose into view. There was the afternoon glitter of Lac Rond tucked in amongst the rolling hills. Nearer at hand, the green blanket of the forest crept out of the wrinkled uplands and took a peek at oblivion over the scalloped edge of the sky cliff. Thin plumes of smoke, the telltale signs of human endeavor, curled from behind a ridge to the left. There, on a promontory of rock overhanging the endless fall, was des Zephyrs’s light tower, its reflector flashing rhythmically.

“Aren’t we coming in a little high?” Jean-Claude asked. Skyships could not fly over land—his academy instructors had said aetherkeels needed a certain amount of air to support them, and flying over rock robbed them of buoyancy—and the St. Marie seemed to be aimed at a hillside.

Captain Jerome gave a long-suffering sigh. “You can’t steer a skyship to where her destination is. You have to steer her where that destination is going to be. Helmsman, make ready to slip. Steer to port on my mark. Reef the main sails and level the beam screw.”

“Aye. Steer to port. Reef the mains. Level beam screw. Aye!” replied the helmsman. Farther down, the boatswain picked up the cry, bellowing a series of orders that must have made sense to the crew, for they scampered about as if the Breaker herself were nipping at their heels. Lines and canvas shifted. The ship shuddered as if in anticipation.

“Steering a skyship requires forethought, strategy, calculation,” Jerome said. “Helmsman, now!”

The helmsman leaned into the wheel, and the huge fantail rudder flagged to the left.

“You might want to hang on to something,” Jerome said mildly.

Jean-Claude grabbed a piece of railing that no one else seemed to be using and swallowed hard. The ship nosed to the left, turning away from land, then rolled over some invisible frontier and began to tilt and slide to the right, until Jean-Claude swore it was going to flip over and throw them all to their deaths. He clung to the rail as the ship tried to fall out from under him. Wind buffets sent his feet sliding. Blood flowed from his mouth where he had bitten his tongue.

The St. Marie veered to a course nearly parallel to the sky cliff, angling steadily downward, picking up speed . . . gliding. The turbulence dissipated. It felt like the ship was tobogganing down a smooth, icy hillside with only the occasional rippling bump. With effort, Jean-Claude unclenched his white-knuckled fingers. “What happened?”

Jerome cupped one hand and twirled his finger over it. “Large masses like skylands produce an aetheric vortex, and the vortex has grooves in it. Poke a hole in the bottom of a bowl full of water and you’ll see what I mean. We’re riding one of those grooves down and toward the center. This one should take us right under des Zephyrs’s light tower. Then we deploy braking sails and pop up like a cork in the harbor. Of course . . . timing is everything.”

“You are a madman,” Jean-Claude said, and Jerome tipped his tricorn, taking it for the compliment it was.

The St. Marie drew level with the cliff wall, a pockmarked scarp a hundred feet high. Then they passed below the rim where the sinking Solar illuminated the belly of the skyland, a vast downward-pointing cone of rock bristling with an upside-down forest of salt-encrusted, aether-emitting cloud-coral stalactites that kept the skyland aloft.

The last leg of the voyage progressed as safely and quickly as Jerome had promised, but not nearly fast enough for Jean-Claude. Six weeks he had spent on this cursed vessel, racing to the capital and back, to plead with His Majesty on behalf of the wicked, wretched Comtesse des Zephyrs. He would just as soon have pushed the vile woman and her villainous relations off a sky cliff. Alas, what duties le roi commanded, his most loyal, most junior musketeer must perform, and he had said des Zephyrs’s bloodline must not fail.

In truth, Jean-Claude suspected that le roi’s position atop the house of cards that was the Célestial nobility was not nearly as stable as his public demeanor suggested. His most recent war had not been a success, and by its undue protraction it had seriously depleted the empire’s ability to compete for land in the unexpectedly profitable new continent, Craton Riqueza. The kingdom of Aragoth had found a way to traverse the Sargassian Still, that great belt of dead air between the northern and southern sky that had so vexed the navigators of the last century, and they had come back with wondrous tales of a new land, backed up with chests of gold and sacred quondam artifacts. As Aragoth’s fortunes rose, so did l’Empire Céleste’s fall, at least by comparison. Thus, Grand Leon was busy appeasing his nobles, including the execrable des Zephyrs, while he gathered his strength for some new far reaching scheme. Grand it would be, of that there was no doubt. Le roi had no interest in any prize smaller than a continent.

From his cabin, Jean-Claude collected a large painting of His Imperial Majesty, le Roi de Tonnerre, Leon XIV. The painted face glowered dyspeptically at him, as if to chastise him for his rude handling. Jean-Claude covered it with a sheet and secured it at all points by wrapping both arms around it. Damned ridiculous thing.

When he scrambled from the shore boat onto the solid stone landing at the quay, his legs wobbled from sheer relief. It didn’t matter in the least that skyships were held aloft by precisely the same incomprehensible forces that held up skylands; the skyland didn’t feel like it was going to fall out from under him. He would have dropped to his knees and kissed the stable ground if he hadn’t been met by Pierre, the comte’s chamberlain, a diffident man with a rabbitlike twitch to his lip.

“Jean-Claude, Jean-Claude. Thank the Builder and Savior you’ve come,” Pierre cried, breathless and flushed. “It is the comtesse. It is her time. Even now she awaits only her roi’s blessing.”

“So soon?” Jean-Claude felt as if someone had slugged him in the gut. Even with all his delays in getting here, he ought to be well forward of the mark; the physicians had told him the Comtesse des Zephyrs was not supposed to deliver for another week at least. This was ill news . . . at least for des Zephyrs.

“She is in considerable distress. Her wails were quite piteous.”

“Haste then. Haste!” The strength of duty surged within Jean-Claude. Clutching the painting, he dashed up the cobbled street and leapt aboard the comte’s carriage, displacing the whip man toward the center of the bench. “Drive, man. Ply that scourge!”

With a snap of his wrist, the whip man sent the coach horses racing. Pierre, not quick enough, chased after them for a few strides, then bent over, coughing in the dust. Jean-Claude’s heart thundered in time to the horses’ hooves. If only his honor would allow him to fail his sworn mission, this could be the end of des Zephyrs’s line. Le roi’s long-standing decree that Sanguinaire ladies must personally attend him at the hour of their delivery or else have their whelps denied names and decreed bastards was just another link in the endless chain by which he bound the nobility to his will. Normally, gravid dames were forced to travel to his palace to give birth, an inconvenience that kept most ladies of childbearing years from ever leaving Rocher Royale and required their husbands to visit them often.

Ah, but the Comtesse des Zephyrs had already miscarried so many times, and this pregnancy had been so terribly complicated . . . and so Jean-Claude had been dispatched to plead the comtesse’s case to le roi. Would he deign to spare one of his most ancient and closely bred bloodlines, or would des Zephyrs be allowed to perish? Alas for Jean-Claude’s eloquent tongue and His Majesty’s good sense, for he had sent his portrait as surrogate, his idea of a compromise, so the vile family might linger into another generation . . . if Jean-Claude was on time.

Scattering peasants, townsfolk, goats, and chickens, the carriage raced through the town of Windfall and thundered out the hinterland gate, past the queue of carts waiting for nightfall to bring their goods inside the walls.

Ahead, des Zephyrs’s estate stood atop a massive acropolis. At its foot stood the Pit of Stains, a half-round theater in the ancient Aetegian style, carved out of solid rock. Jean-Claude’s heart tightened as the coach approached that venue. In other cities, amphitheaters were full of life, used to enact plays and celebrate festivals, but the Pit of Stains was desolate, barren save for a pattern of reddish discolorations scattered about like fallen maple leaves, the lingering traces of the Comte and Comtesse des Zephyrs’s cruelty.

Once a month, the comte’s white-liveried guards paraded ten condemned men, women, and children to that stage. Some of the victims were actual criminals, but most were rounded up for the spectacle on false pretense or none at all. Witnesses, the families of the damned, were herded into the theater seats, and everybody waited until the comte and comtesse arrived, at high noon, to perform the execution.

The prisoners were unshackled and then the comte and comtesse released their sorcery. Des Zephyrs were saintborn, direct descendants of the Risen Saints. As such, they carried la Marque Sanguinaire, the mark of one of the ancient sorceries, in their veins. Their shadows were not gray like those of normal folk, but crimson, and they stretched away from the aristocrats’ feet like great elastic ribbons of blood. These bloodshadows flowed onto the stage, surrounded the prisoners, and slowly constricted.

There were rules to this game. Only the first two prisoners to be touched by the shadows were killed. Nobody wanted to be amongst that count, so as sanguine shadows filled the amphitheater floor, the condemned huddled together on a shrinking island of light, scrambling to be as far from the creeping doom as possible, pushing each other out of the way, begging for a mercy that would not come.

All too quickly, the victims turned on each other, the stronger thrusting the weaker into the oncoming flood. Rarely, a brave soul would sacrifice himself or herself to save the others, but as a single selfless act was not enough to turn the tide, it rarely prevented a brawl to avoid the fate of being the second victim.

Jean-Claude had borne witness to the ritual once and still shuddered at the memory. The comte had not smiled—he never smiled—but his eyes gleamed in delight as his bloodshadow devoured a man not much younger than the musketeer. The sorcerous stain entered the boy through his shadow. His flesh turned transparent and melted, his body losing shape and coherence as the red tide absorbed him, destroying him down to the very soul.

Terrified and horrified, Jean-Claude had done nothing to stop the murder. Legally there was nothing he could do. By most ancient and sacred law, the Sanguinaire were owed their due. Shadow feeding did not have to be fatal or even greatly hurtful. Other Sanguinaire nobles took their due from their subjects without recourse to murder. Many nobles paid quite well for the service and afforded their donors places of honor that had folk vying for the privilege. Not the des Zephyrs.

“Only a full feeding gives full benefits,” the comte proclaimed. “Only fear satisfies the shadow. Only death sates it.”

When the bloodshadows withdrew, nothing was left of the boy but a soul smudge, a patch of russet that seemed to writhe just beneath the surface of the stone, squirming in the sunlight. The remaining prisoners had been pardoned. They returned to the relief of their families, and, all too often, the reproach of the kin of the slain. “You killed my son.” “You pushed my sister in.” “You should have died.”

And that was the elegant mechanism of the spectacle of slaughter. It kept the downtrodden divided, almost as resentful of each other as of the so-called nobles who commanded and performed the murders.

The coach sped by the killing ground, and it seemed to Jean-Claude that he could hear the ghosts of long-ago screams. And this is the bloodline I must preserve. If the comtesse’s child lived and thrived, it would join its parents on that platform, and there would be three fresh smudges on that platform every month. That thought filled Jean-Claude with revulsion, but le roi’s desire had been specific. Three peasants a month to keep the des Zephyrs happy were but the crumbs wiped from a silver plate from Grand Leon’s perspective.

Jean-Claude prayed the comtesse would die in childbirth . . . of course that would allow the comte to remarry, perhaps to a more fertile wife . . . Not desirable. Let her live, then, but crippled, and let the child be stillborn. Better for everyone that way, even the child; no child of the des Zephyrs would have a chance of escaping their corruption.

Atop the acropolis’s plateau sprawled the Château des Zephyrs, sweeping arms of pale marble reclining indolently on a rolling, grassy sward. As daylight faded, alchemical lamps flickered to life in every window, as was the custom in Sanguinaire houses. For there can be no shadow without light.

Jean-Claude leapt from the carriage before it stopped, alighted on the landing, adjusted the portrait, and burst through the silver-trimmed double doors even before the doorman could throw them wide.

“The master bedroom, monsieur,” the doorman called after Jean-Claude’s retreating back, but Jean-Claude had already mounted the stairs and made the turn. From the wide-flung doors at the end of the corridor came a piteous grating wail. The comtesse had a voice like shattering glass at the best of times. Her distress in labor sounded like a cat fight in a porcelain shop.

Jean-Claude slid to a stop just outside the threshold, straightened his rumpled tabard, and marched in. “Your Excellencies,” he said, for the comte stood, powdered and dressed in his finest whites, sipping a chalice of red wine and looking more bored than dutiful, at his wife’s bedpost. The air swam with a nauseating swirl of blood stench, wine fume, and sweat.

Comtesse Vedetta lay in bed, breathing shallowly, her upper half absurdly dressed for a party, white wig askew, her lower half obscured by a privacy screen. When Jean-Claude had left on his errand, her thin face had been drawn and haggard. Six weeks on, she looked skeletal, an appearance exaggerated by the sweat-streaked white face powder and the black smudges of mascara around her eyes. Only the flint in her eyes gave notice of a jealously hoarded reserve of strength and malice. By the foot of the bed stood a worried-looking midwife and a man in clerical robes.

The Temple man was short and squat and carried a heavy satchel slung over one shoulder. His cassock had a black trim, and he wore a black mantle embroidered with interlocking gears, screws, and pistons, the Ultimum Machina, sigil of an artifex. Where his left eye should have been was a bulging orb of quondam metal, the color of bronze with a purple patina, set with a large red gem. Such prostheses were common amongst the Temple’s highest ranks, marking their dedication to the Builder’s perfection. As far as Jean-Claude was concerned, anyone who thought plucking out their own eye was a good idea probably wouldn’t recognize perfection if it walked by naked waving a flag.

But what in the darkness of Oblivion was such a potentate doing here? There were only eight artifexes in all the Risen Kingdoms, one for each of the remaining saintblood lineages. Only the Omnifex in Om stood closer to the Builder, and he only because he had a taller hat. Jean-Claude had to wonder what strings the comte had pulled to ensure the man’s attendance on his offspring’s birth.

The artifex glowered down at the comtesse like a judge at a trial. The glow from his artificial eye cast her in a bloody crimson hue. With aspergillum in hand, he sprinkled her with blessed water while delivering the ritual litany of admonishment given to all women on their birth bed. “Remember that this is your duty, your penance for Iav’s great sin. She thought to steal the secret of life from the Builder, and so must new life be torn from your flesh.”

“Silence, wretched cur!” the comtesse snapped, her mouth as foam flecked as a rabid dog’s.

The artificer paid her no heed but continued in a gravelly voice, “This pain is your due. This trial is your judgment. Succeed and you may be forgiven, your soul restored when the Savior comes. Fail and you shall fall into the pit from which there is no salvation.”

“Jean-Claude,” said the comte blandly, “how good of you to join us. I trust your mission is accomplished.” Only a slight tightening of his stance hinted at how desperate he was that his statement be confirmed; if le roi had rejected his petition, then these last nine months had been a waste, along with all the resources he had dedicated to shoring up his leaky dam.

“You . . . servants’ . . . entrance,” the comtesse spat at Jean-Claude, her normally eloquent venom reduced to breathless grunts.

Jean-Claude bowed to her. Vile harridan. “Your Excellency, forgive me, but I did not think you wished to insult le roi by bringing him through the chicken yard. By his decree, I present His Imperial Majesty le Roi de Tonnerre, Leon XIV.” He unveiled the portrait with a flourish.

The comte made a leg for the painting, “Your Majesty.” The midwife curtsied. The artifex made a sign of respect. Even the comtesse managed to bob her head at it.

Jean-Claude settled the painting on a long-backed chair. “His Majesty instructs me to inform you, from his lips to your ears, that as this portrait is his presence, so am I his eyes and ears in this matter.” He presented a letter affixed with the royal seal.

The comte looked vaguely ill, which put him more on par with his wife, but accepted the letter. The thought of a lesser man judging the fitness of his offspring would no doubt disrupt his humors for days.

The comtesse’s body convulsed weakly, and she groaned. The midwife ducked behind the privacy curtain. “One more push, Excellency.”

The comtesse gnashed her teeth and curled her clawlike fingers into the sweat-stained silk sheets. “Wretched . . . sow!” she spat between contractions.

So temperamental was her womb that the comtesse had been restricted to a peasant’s diet of boiled oats, beans, eggs, and garden vegetables for the whole duration of her gravidity. For the last few months she had been forbidden even the slightest exercise. The physicians had even gone so far as to forbid her the use of her sorcery for fear of upsetting her delicate humors. Over the months, her limbs had withered even as her belly bloated. Even her carmine shadow looked thin and gray, almost ordinary.

Please let the bloodshadow wither and die. There was no greater terror for the Sanguinaire than to be blighted and lose their sacred sorcery. Such unfortunates were called unhallowed and were deprived of much of their status.

“One more push,” pleaded the midwife.

“I’ll . . . show you . . . push!” The comtesse groaned, bearing down on the bulge in her belly.

Jean-Claude assumed a parade rest and watched the comtesse’s struggle with as much outward dispassion as he could muster, even as he willed disaster and despair on her efforts.

“It’s coming!” the midwife cried.

The comtesse screamed and squeezed with a demonic strength.

“I have its head, Excellency, just one more push.”

“Curse your . . . damned pushes!” She grunt-pushed once more and then gasped, her flinty eyes open wide.

“It’s out. I’ve got it.”

The comte’s eyes lit up. “Is it a boy? A son?”

The midwife examined the child. Her face fell.

“What is the matter, you stupid cow?” the comtesse snapped. “Is it whole?”

The midwife’s voice was very small. “It . . . it is stillborn, Excellency.”

The comte’s expression hurried though a range of emotion from dismay to frustration. The comtesse sagged back in her pillow, limp and almost lifeless without the energy of her anger.

Jean-Claude’s antagonism proved bitter, for his heart twinged painfully at the announcement of the stillbirth. Rationally, logically, this was probably the best outcome for everyone. Even so, it seemed unjust that the comte’s and comtesse’s heartbreak and despair could only come at the cost of an innocent life. The child was not to blame for its parents.

The artifex produced a cloth sack from his satchel and stepped forward to take the child from the midwife. He rumbled, “Comte, Comtesse, you have my condolences. I will perform the rite of kind passing.”

As the midwife made to shroud the baby’s face, a thin brief mewl cut through the silence. The comte’s head snapped up. “What was that?”

“Nothing, Excellency,” said the midwife without looking up. “Just the death rattle.”

The comte subsided, but Jean-Claude lunged to the screen and peered over. The baby shouldn’t have had any breath to be its last. As a farmhand, he had witnessed the births of many animals, but never of a fellow person. This was definitely more alarming. Cows and sows didn’t have to distend like that. The midwife cradled the child in one arm and firmly pressed a cloth to its face with the other.

“Witch!” Jean-Claude darted around the blood-soaked end of the bed.

“No, monsieur!” the midwife cried.

Jean-Claude tore the newborn from the midwife’s grasp and planted his boot in the woman’s belly, sending her sprawling to the floor.

“Musketeer—!” the artifex bellowed, but Jean-Claude whipped the cloth from the little one’s face. It began to wail.

Alive after all, the newest des Zephyrs was clearly a girl, and there was nothing wrong with her lungs. This was not as good for the des Zephyrs as a son, but certainly no cause for despair. She’d be worth a lot in the marriage market. So why had the midwife tried to murder her? Had she been paid, or was this to have been revenge for some past injustice, or . . .

It took him a moment to see what the midwife’s trained eye must have noticed immediately. Under the ragged, slimy veils of birth, the child’s left hand was a pudgy fist, but her right wrist tapered off to a stunted hand with only one twisted finger. Poor thing.

Jean-Claude’s heart sagged in its rigging. The Almighty Builder’s devout followers believed deformities such as this marked unclean souls, abominations, the Breaker’s get. Just as Jean-Claude would have slit the throat of a two-headed calf, the pious midwife meant to dispatch this child, deny her a name and consign her to the sky. Jean-Claude could not imagine the des Zephyrs would do any different once they saw the facts for themselves. They would not want their name sullied with rumors of impurity. They would kill the girl and bemoan the loss of their chance at dynasty and then carry on as before, but with extra self-pity.

“By the Builder,” the artifex said, his posture and tone horrorstruck. “Witch!”

The midwife’s face went pale. She looked back and forth between the cleric and the comte. “No! Master, you—”

“Silence!” roared the artifex.

“You tried to kill my child,” growled the comte. His crimson shadow stretched and slid, an oily ribbon, across the white marble floor.

“No, please!” the midwife pleaded, but the comte’s bloodshadow seized her shadow by its neck and shook her like a terrier with a rat.

With a flick of his wrist, the comte flung the woman across the birthing chamber and onto the balcony. She struck a pillar with a resounding crack and then lay still.

Too late, Jean-Claude said, “Excellency, stop! Ah, we should have questioned her, found out if she was working with others.”

“Time enough for questions later,” the comte said. “Have I a son?”

“A daughter,” Jean-Claude said. At least until they discovered her peculiarity, and then they would be thanking the dead midwife for her initiative and discretion. Perhaps they would affix a memorial plaque to the pillar where the comte had smashed her.

The artifex reached for the child. “Allow me to inspect—”

“Let me see her,” snapped the comtesse, “I must claim her.”

“Of course,” Jean-Claude said automatically, even while shielding the girl from the artifex with his body, delaying the inevitable. These folk would give this poor helpless scrap to the sky, and there was nothing Jean-Claude could do to defend her.

And then the squalling stopped with a hiccough. The babe opened her eyes. Blue eyes. Blue as the crystal cold sky of the uppermost heights, pale, translucent, and deep as the heavens.

Her pudgy left hand reached up and touched Jean-Claude on the nose. There was a rushing in his ear and he felt as if he were falling, as if he’d finally managed to fling himself off a tilting skyship.

“Hand her over.” The comte’s voice seemed to come from a very long way off, but it was no less menacing for that. He would murder the child.

Over my cooling corpse.

But Jean-Claude had no authority in this. The girl needed a greater champion.

But the only man who could effectively lay his hand in protection over his smallest subject was Grand Leon, and he was not here, at least not in person. Jean-Claude’s gaze strayed to le roi’s picture on the chair. It was not a current likeness. It showed Leon XIV in the prime of his life, with broad shoulders and a head of dark ringlets that hung past his shoulders, not heavy jowled with hog fat around the middle as Jean-Claude had last seen him.

But Jean-Claude was le roi’s eyes and ears. Why not his mouth and tongue? Except, he hadn’t been given permission to speak in Grand Leon’s name . . . or had he? “Do not let des Zephyrs’s line perish from the world,” seemed to authorize nearly any action to protect this child.

Yet, if Jean-Claude dared invoke le roi’s name, he would be called to account, and he knew damned well Grand Leon cared only for this child’s value as a political pawn. Le roi would not be pleased to have an abomination so close to the royal blood . . . unless Jean-Claude phrased his explanation very carefully. The Comtesse des Zephyrs was le roi’s maternal cousin, and her mother had helped lever le roi onto the Célestial throne against the wishes of the Omnifex. I feared your dear aunt’s blood should fade entirely . . . a favor to her that she should be eager to repay . . . Yes, that had the right ring to it. I was only thinking of you, Majesty.

What are you thinking, boy? You can’t lie to Grand Leon!

Well, not a lie as such. He would leave certain things out of his report, edit it for brevity. There had been an entire class at the academy dedicated to herding aristocrats. It had been deceptively titled Proper Obeisance. As it was listed as an elective, the academy’s noble scions had ignored it like a bad smell. Jean-Claude had found it . . . instructive.

You are the Breaker’s own get, mongrel, and you are going to get yourself killed.

“Give her here, you idiot,” the comtesse demanded.

A wicked humor twisted Jean-Claude’s cheeks into a smile. Perhaps he would rue this day, but if so, it would be for defending a child, not for abandoning her.

“Of course, Your Excellency,” he said. “But first, her name. As the duly appointed representative of His Imperial Majesty, le Roi de Tonnerre, Leon XIV, I present you with”—the name had better be a good one. Le roi’s beloved mother perhaps? Yes. May she rest in peace—“Princess Isabelle.”

Copyright © 2017 by Curtis Craddock

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window