opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window After ten years in Paris, where she learned photography and became part of the movement that invented modern art, Chicago-born, Irish-American Nora Kelly is at last returning home. Her skill as a photographer will help her cousin Ed Kelly in his rise to Mayor of Chicago. But when she captures the moment an assassin’s bullet narrowly misses President-elect Franklin Roosevelt and strikes Anton Cermak in February 1933, she enters a world of international intrigue and danger.

After ten years in Paris, where she learned photography and became part of the movement that invented modern art, Chicago-born, Irish-American Nora Kelly is at last returning home. Her skill as a photographer will help her cousin Ed Kelly in his rise to Mayor of Chicago. But when she captures the moment an assassin’s bullet narrowly misses President-elect Franklin Roosevelt and strikes Anton Cermak in February 1933, she enters a world of international intrigue and danger.

Now, she must balance family obligations against her encounters with larger-than-life historical characters, such as Joseph Kennedy, Big Bill Thompson, Al Capone, Mussolini, and the circle of women who surround F.D.R. Nora moves through the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, and World War II, but it’s her unexpected trip to Ireland that transforms her life.

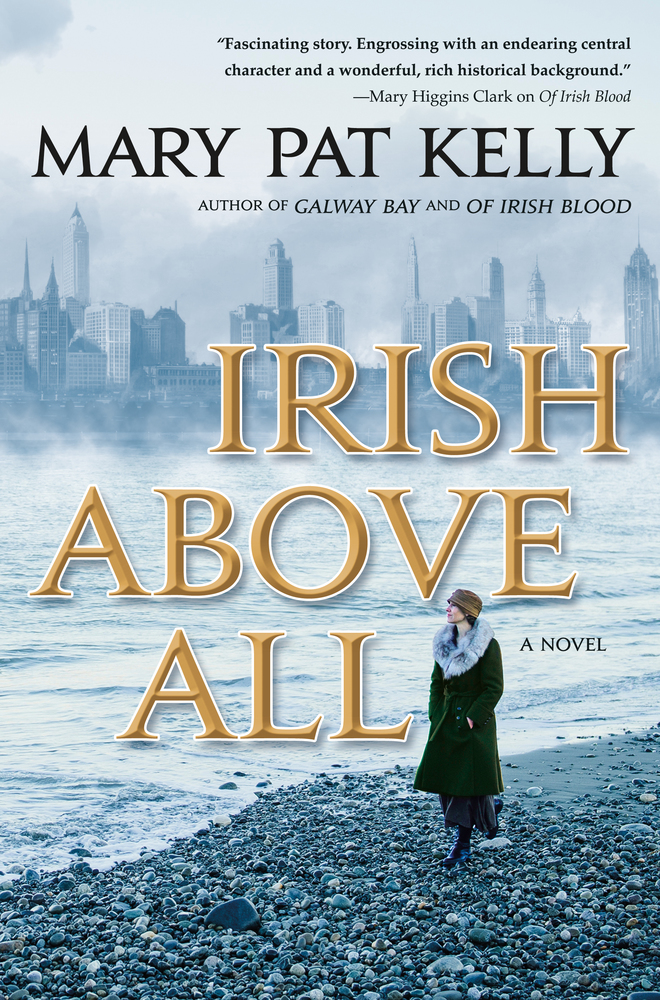

Irish Above All by Mary Pat Kelly will be available on February 5th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

1

March 21, 1923

“Come on, come on.” After rushing from New York to Chicago in twenty hours thirty-four minutes, a record the conductor told me, the 20th Century Limited seemed to be panting its way along the last yards of track into LaSalle Street Station. I was desperate to get off the train. I’d left Paris two weeks ago in response to Rose’s telegram, “Mame dying.” Mame McCabe Kelly—Rose’s sister, my brother Michael’s wife, and my pal since we were girls. She was still alive, but weak, Rose had told me on the phone last night when I called from New York as soon as the Normandie had docked.

Mame’s doctor had told Rose there’d been some complications after “the operation for female problems.” He’d been vague, Rose said. A hysterectomy, probably an infection. Mame was not recovering. The prognosis was not good.

“What can you expect,” I’d said to Rose. “Mame had five children in seven years and she was thirty-one years old when she gave birth to the first. I mean, dear God. . . .”

“Nonie, please,” Rose had said. “She and Michael wanted a family and . . .” Rose had stopped. She and her husband John had tried so hard for a baby. Three miscarriages before I’d left and probably more since.

“Your sister Henrietta won’t let me see Mame,” Rose had said.

“I’ll handle Henrietta,” I’d said.

“I just think if the three of us were together again it might give Mame strength,” Rose said.

Finally the train stopped. The doors opened. I was down the stairs and onto the platform and there was my cousin Ed waiting, wearing a bowler hat and spats. Always dapper was Ed.

“Welcome home, Nonie,” he said. After ten years of being Nora, I was Nonie again. My nickname in the family. Ed was bringing me back into the fold.

He tipped his hat. Not much gray in his red hair. Three years older than me, so forty-seven. No bulge of fat under the double-breasted jacket of his pinstripe suit. Does he still run along the lake in the morning? He’d picked up the habit when he was boxing champion of the Brighton Park Athletic Association. His start in politics. I opened my arms but he stepped back. No hug. Not in public with a uniformed railway official next to him.

“Any word?” I said.

“No change as far as I know. We’ll pick up Rose and John Larney and go straight out to Argo.” Ed’s mother and Rose’s mother-in-law, Kate Larney, were sisters. One more strand in the web that bound us all together.

“Let’s go,” Ed said to the official who led us off the platform.

A Red Cap followed behind with my Gladstone bag. “No other luggage?” Ed asked me as we walked through the station.

“No,” I said, “just this and my camera bag.” I planned to return to Paris as soon as . . .

Ed took the bag from me and gave the Red Cap a dollar. “Thank you very much,” the Negro man said.

“You a South Sider?” Ed asked.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Bronzeville.”

Ed nodded. We walked toward the LaSalle Street exit.

“He probably voted for Thompson. The colored people in Chicago will support any Republican running because it’s the party of Lincoln. But we finally beat Big Bill Thompson. We’ve elected a good man, Nonie. Our first Irish Catholic mayor. Bill Dever. Decent Dever.”

“Well, that’s good,” I said.

We were out on Canal Street now. “More people and cars in the streets than I remember, Ed.”

“Chicago is growing,” Ed said. “The population has doubled since you left. The city limits are expanding. That’s why we have to get a respectable government. Change our reputation.”

“I know, Ed. Even in Paris when I said I was from Chicago someone would do this . . .” I made a tommy gun with my hands and pointed. “Ack, ack, ack.” Ed shook his head. “Thompson took millions from Capone. Gave him the run of the city. Dever has already forced the Outfit’s headquarters out of Chicago into Cicero. It’s a start. With Dever in office, we’re moving ahead,” he said.

Ed walked up to a long expensive-looking black automobile. Took keys from his pocket and unlocked the door.

“Nice,” I said to him. Ed had been doing alright for himself when I’d left— a good city job as an engineer—but this was a rich man’s car. Not the time to ask questions, but I wondered.

“I started buying Packards because Mary liked to take drives out to the country on Sundays,” Ed said.

Mary. Ed’s wife. Poor girl. Only twenty-five when she died in the 1918 flu epidemic. Pregnant. Terrible that women who were expecting were the most susceptible. Both she and the little one gone.

“I’m so sorry about Mary, Ed,” I said. “I should have mentioned her right away.”

“Nothing to say really. Everyone tells me time will help. But it’s been five years and I miss her every day.”

“So sad,” I said.

“I wonder would the baby have been a girl,” Ed said. “Mary wanted a daughter and Ed Junior was looking forward to a little sister.”

I reached out and squeezed his forearm. “Oh, Ed,” I said.

“She’s buried in Calvary. A Celtic cross in Connemara marble. She’d be pleased.”

“I want to visit her grave,” I said. Some comfort to know the one you loved was tucked into a lovely grave, I thought.

Ed held the passenger door open for me. I got in. He put the bag in the back seat. Sat in the driver’s seat. I pulled the skirt of my suit down over my knees.

“That’s pretty short, Nonie,” he said. “And is that a man’s jacket you’re wearing?”

“It’s the fashion, Ed,” I said. “Haven’t Chicago women turned up their hems?”

“Not ones your age,” he said.

“In Paris, forty-four is not old,” I said.

“But you’re not in Paris now,” he said.

I’d spent ten years as Mademoiselle Photographie, a woman with a profession who earned her own living and was friendly with artists and writers. I’d been part of a group of Irish rebels clustered around the Collège des Irlandais near the Pantheon.

Honora Bridget Kelly was my baptismal name. I’d been called after my grandmother, Honora Keeley Kelly, but I preferred the more modern Nora. Granny’s name connected her to Ireland and a history I’d only recently discovered. Now I would be Nora, Nonie in the family, on my way to my brother’s house to look after his sick wife. Doing my duty. I was a Kelly of Chicago. A meat-and-potatoes town where grown men did not paint strange pictures or write obscure books and women lived for their husbands and children, of which I had neither. I had to wonder would the Biblical father have slaugh- tered a calf for a prodigal daughter? Probably would have told her to get into the kitchen and start the dinner.

Ed turned west on Jackson Boulevard. Though the Kellys and Larneys were South Siders, he told me Rose and John had broken with tradition and were living in a bungalow on the West Side.

“It’s closer to police headquarters, at Twenty-Sixth and California,” Ed said. “John’s working out of that station now.” Excusing the defection.

I’ll see Rose in a few minutes, I thought. Rose, Mame, and I. My brother Michael called us “The Trio.” Three young women marking the century’s turn with a vow to live our own lives and support each other. We would not marry at sixteen as our mothers had. We would have jobs that used our intelligence and skills. We would march and demonstrate until women could vote. Until our rights were recognized.

And we had won. The three of us had started at Montgomery Ward’s as telephone operators, taking orders from all over the country. We were required to sound like proper American ladies. Another trap. But we’d burst through the restraints that the anti-Irish Miss Allen had put on us and moved up. Mame became the private secretary of the vice president of Montgomery Ward, mastering that new machine, the typewriter. Rose and I set up our own Ladies Fashion Department. Twenty-five-year-old successes. The new women. Confident and unafraid and then, well . . . Rose fell in love with John Larney, married him. Not proper for a married woman to continue working. Not when she wants a family. And Mame was secretly in love with my brother Michael, the forty-five-year-old bachelor who didn’t dare declare his love for her openly for fear of our sister Henrietta. Henrietta, nearly seven years older than I am . . . she was just fifteen when she married a cousin of ours called Bill Kelly and moved with him sixty miles south of the city to a small Illinois farm town. I remembered visiting her in the little house surrounded by fields. Bill worked long hours farming and in a local food processing factory. Henrietta had three little ones in six years and then suddenly she and the children were back home with us. Bill Kelly dead in an accident at the factory and Henrietta a widow at twenty-two. Granny Honora had tried to explain to me that Henrietta was cranky all the time because she was mourning her husband. But I don’t think Henrietta gave Bill Kelly much thought. She’d only known him such a little time.

No, Henrietta was mad because she didn’t have her own house. Never occurred to her to get a job and work for the money to go out on her own. Henrietta had been a maid in one of the Prairie Avenue mansions when she was fourteen.

“I’m never taking orders from some prune-faced woman again. I married Bill Kelly so the only floors I’d have to scrub were my own,” she’d told me when, after a year of living with us, I repeated what my friend’s mother, Mary Sweeney, had said, that Henrietta could get a good job as a housekeeper.

We pulled up in front of John and Rose’s bungalow. Rose came running out. I hurried up the steps to meet her. We stood on the porch hugging, and I started crying. I’d missed her, missed Chicago, missed myself, really, the Nora that should have been. I loved my life in Paris and would be back there soon, but . . .

John walked out. “Good to see you, Nora. Hello, Ed.”

“And Mame, Rose?” I asked.

“Very sick, Nonie. That’s what Stella Lambert, their neighbor in Argo, says.

She calls me. I haven’t seen Mame in a month. Your sister Henrietta is like a woman possessed. She won’t let me in when I go there. Poor Michael is in such a fog, spends hours just sitting next to Mame’s bed. The kids are terrified. And Henrietta’s, well, she’s hard on the little ones.”

“Don’t tell me,” I said. “Spare the rod, spoil the child. Her favorite saying. I’m home now, Rose, and I’m well able for Henrietta.”

An hour later we arrived at Michael and Mame’s big corner house, surrounded by trees and grass. A very small town and very pleasant-looking Summit was, even if the huge corn starch factory made everyone call Summit “Argo.”

Henrietta’s dream come true.

Toots, her youngest son, opened the door. In his thirties now, a bit spindly with a belly that slopped over his belt, but grinning with the same smile he’d turned on all of us when he was a child, making us laugh with his dancing and singing (“A regular George M.!” Mam had said). But it wasn’t so funny when they expelled him from St. Bridget’s school. Hard place to get kicked out of, if you were a Kelly.

We’d all been baptized there. Granny Honora had worked in the parish office in the year dot, and Michael, my brother, always had put wads of bills into the collection basket. But Toots had stolen the other kids’ pennies and lied to beat the band. Deliberate badness too. He was only five when I’d seen him take Granny Honora’s clay pipe and drop it with great concentration on the slate floor in front of the hearth. Crying, of course, and saying it was an accident. Then he’d begged a dime from Michael to go buy another pipe for Granny, though pipes were a nickel. He kept the change. A chancer.

“My little fatherless boy,” Henrietta would croon to him, and I’d think, Ah, well.

But then I was fatherless myself, and hadn’t my da and aunt and uncles lost their father young and suffered in Ireland as no children should? Yet they were decent. Each and every one of them. I mean, dead fathers were two for a penny in Bridgeport.

“I’m afraid Toots has a wee quirk, Henrietta. You’re not helping the boy by indulging him,” Mam had said to her when he was ten and had been expelled from a Bridgeport public school.

But Henrietta had let him lay in bed until noon and then he’d run errands for her, often coming home with half the groceries and some story about giving them away to a woman with two children who needed food. Mam, who had a horror of people going hungry, would only nod, just in case he wasn’t giving out his usual line of rubbish and someone had really been in need. I talked to Michael once, but he’d only shrugged. Peace at any price, our Michael.

In those days, Michael was hardly home anyway, going off on jobs or out to boxing matches or Democratic politics. A big man for banquets, Michael was, master of ceremonies at the Knights of Columbus and a dozen others. Of course, in those years, he was secretly courting Mame and I had been besotted with Tim McShane, so no one had taken a hand with Toots. Henrietta, so stern with her other children, made a fool of herself over her baby. Not that I’m one to talk about blind love.

“So, the prodigal returns,” Toots said.

“Show some respect for your aunt,” Ed said to him.

“Oh, I have great respect for anyone who gets out of this town,” he said. And then there was Henrietta. The same gray hair pulled back into a bun, and could that be the same purple housedress she wore ten years ago? “You,” she said to me. And, “You,” turning to Rose and John.

“You are not needed here.”

Ed spoke up. “Now, Henrietta, isn’t it grand to have Nonie home? Your own sister.”

“No sister of mine. She gave up that right,” she said.

“And what about my sister?” Rose said. “I’m here to see Mame.” “Which she will do, Henrietta,”

Ed said. “And no scenes.”

“Please, Henrietta,” I began.

But she stuck her finger in my face. “You brought evil into this family! Your hoodlum boyfriend attacked me!” Screaming the words.

“Stop it, Henrietta,” I said. “For God’s sake, do you want the children to hear?”

But it was too late. Two young girls stood in the parlor doorway, one holding a baby in her arms. Next to them, a young boy held the hand of a small girl—all looking up at us. Michael and Mame’s children—ten, eight, six, four, and two years old.

The boy and littlest girl rushed into Rose’s arms, and the older two moved close. Rose took the baby.

“Aunt Rose, I’m sorry,” the oldest girl said.

Rose embraced them. “Sorry? For what?”

It was the little fellow spoke up. “Aunt Henrietta said we were so bad that

Aunt Rose and Uncle John wouldn’t visit us anymore.” He walked over to John. “She said you would put me in jail and that I may even die in the electric chair.”

John picked him up. “Your aunt Henrietta says some very foolish things, Mike. You’re a good sturdy lad and a comfort to your mother. Why would I put you in jail?”

Henrietta screamed, “I never said any such thing!”

“She did,” said the oldest girl.

Then Rose said to her, “Come on, Rosemary. And Ann, bring Frances.

We’ll go back in the kitchen. John, bring Mike and Marguerite. You’ll finish your breakfast and then meet your aunt Nonie. She’s come all the way from Paris to see you.”

That’s when Mame called down from her bedroom, “Who’s there?” Such a weak voice.

“Go up to her, Nonie,” Rose said to me.

I ran up the stairs. Wood-carved banisters with stained glass windows set along the wall so the sun threw patterns onto the dark green carpet. A lovely house. All Henrietta had ever wanted, but it wasn’t hers. Demented with jealousy. Dear God, were we better off when we were all poor together?

“Mame, it’s me. It’s Nora,” I said. Very dark in the room, only a little lamp, like a vigil light.

“Nonie! Nonie! Home at last!” Mame said.

“And Rose is here too,” I said.

“Rose? But Henrietta said Rose was too sick to come,” Mame said. “Rose is fine and she’s here, and John too. And Ed.”

“But Henrietta . . .” Mame half sat up.

“Forget about Henrietta, Mame.”

“But she’s been very good, coming in to help with the children. She said no housekeeper would take on five children and a woman as sick as I am. And it wasn’t fair to expect Rose to . . .”

I settled her back on her pillows. “For God’s sake, Mame, don’t you know better than to listen to Henrietta? Rose is here, and I’m here. The Trio together and you’re going to be fine, Mame, and up with those gorgeous kids of yours soon.”

She smiled. “They are gorgeous. The oldest, Rosemary, named for Rose and my mother, and then Ann for your sister—she was great with the children when they were little, but she’s her own life now. Henrietta tells me a policewoman must be on call. And our son was born on Christmas Eve, 1916. We were going to give him Victor as a middle name, a kind of prayer that the war would end. But then Michael said that Michael Joseph Kelly was your grandfather, who died in Ireland, and his own name which he wanted his son to carry on. Marguerite was named for you, Nonie.”

“Me?”

“So many Margarets and Maggies and Peggys and Marguerite is French, and with you in Paris . . .”

“Thank you, Mame.”

“And little Frances is in honor of St. Francis Assisi. I was praying to him because the doctor thought we wouldn’t have any more children. But look at her. Beautiful. And I was just fine until I started bleeding and . . .”

Then Rose was there. “Mame,” she said, and walked over to the bed and pulled the spread straight. “You could use another pillow.”

“Oh, Rose,” Mame said. Rose leaned over and the two of them held on to each other until Mame said, “You’re very good to come, but I didn’t want you to be upset.”

“Upset? Me? Not a bother on me and you’re going to get well, Mame.” She walked over and pulled open the curtains. “Let some sun in here. Henrietta’s been a help but I think it’s time for me to lend a hand. I’ll stay in the room on the third floor. Isn’t it grand to have Nonie home and looking so glamorous? Might even get me to bob my hair. Mame did.”

And I saw that, yes, though her hair was matted, Mame did indeed have a shingle.

“And your dress, Nonie. Puts me in mind of our uniforms at St. Xav’s,” said Mame.

“The designer was raised in a convent school, an orphan, or kind of an orphan.” I started to tell them about how I had become a friend of Coco Chanel and all about Paris, until I noticed that Mame was closing her eyes. I looked at Rose.

She waved me away and I left the two McCabe girls together. I’d come home ready to make peace with Henrietta. But now . . . how could she keep these sisters apart?

I could hear Henrietta’s high-pitched yowling and Ed’s low tones as I walked by the closed parlor door. Leave them to it, I thought, and found the kitchen where the children huddled together around a table. A young colored woman stirred a large pot at the modern stove. Electric.

“Hello,” I said. “I’m Nora Kelly. Their aunt Nonie.”

“About time,” she said. “I’d walk out of here if Mrs. Michael wasn’t such a kind woman. My name’s Jesse Howard.”

So Henrietta had help with the house and the cooking and was still complaining. Jesse ladled what looked like oatmeal into a bowl and sat down at the table.

“Me and Rosemary and Ann will finish eating, then clean up. You take the three little ones out until the war to end all wars is finished in the parlor,” Jesse said.

“But maybe I should—”

“You’re Nonie? Well, she’s been shouting your name. Better hightail it.” I brought the three youngest—Mike, Marguerite, and Frances—out into the backyard. So flat, Chicago and Summit/Argo had no tall buildings to hold back the prairie. It came lapping at our ankles despite the green slatted fence Michael and Mame built to enclose a bit of the wild. They’d stuck in peony bushes and hollyhocks and called it a garden. But weeds and tall grass were scattered throughout the yard. I thought of the Jardins Luxembourg and Parc Monceau, with their obedient flowers and shrubs.

I carried Frances and followed Mike, who led Marguerite and me to the far corner of the yard and a gap in the fence. Just beyond, in the open space bricks were stacked one on another in a square about as high was my waist.

“Our fort.”

“With Bobby,” Marguerite said. “His friend. They fight Indians.”

“They do? Well, did you know that the Kelly family ate their first Christmas dinner in America at the home of an Indian family?”

They shook their heads no.

“Well,” I said, balancing on one surprisingly sturdy wall of the fort, holding Frances while Marguerite and Michael sat in the dirt. “Fadó,” I started. “What?” Michael said.

“Once upon a time,” I said, but I’d hardly begun when a very elegant woman holding the hand of a young boy came walking toward us. “Bobby!” Mike said and ran toward them.

“I’m Stella Lambert,” the woman said. “I see the children are getting dirty.”

My brother Michael arrived just after noon. I saw him from the window as he slowly got out of his car then took one look at Ed’s Packard and started running up the walk, taking the porch steps two at a time.

Henrietta got to the door first but Ed, Rose, John, the children, and I were right behind her.

“Ed, is it Mame? Is she . . . ?” He was halfway up the staircase to the bedroom before Ed’s voice stopped him.

“She’s fine, Michael. She’s sleeping.”

Michael looked down at us gathered below him. “Then why are you all here? Rose, John and . . .” He saw me.

“It’s me, Michael,” I said. “It’s Nonie.”

“Nonie?” He walked slowly down to me, squinting through his black- rimmed glasses. “Nonie, you’re here.”

“I am that, Michael. Just off the boat and the train. I arrived this morning.”

“Oh she’s back alright.” Henrietta stood with her arms folded, Toots next to her.

I paid her no mind, stepped right up to Michael and hugged him hard. “The prodigal has returned,” I said.

Now Mike, Ann, and Rosemary swarmed around Michael, holding his legs.

“Everybody came, Dad,” Mike said.

Michael put his hand on his son’s head. “You want a drink, Ed? John? Tea or something, Rose? Nonie?”

He turned to Henrietta, but Rosemary spoke up. “I’ll tell Jesse to bring some food, Daddy. Come on, Ann.”

Henrietta didn’t move. She’s feathered herself quite a nest, I thought, and what was she doing? Only scaring the kids half to death, practically telling them, “If you’re not good, your mother will die.” Ridiculous. And yet she’d said the same to me when Mam passed away, telling me, “She cried about your life, Nonie. You helped put her in an early grave. I only thank God she was dead before she found out about your final degradation.”

And somewhere inside me, I’d believed her. If I’d married at nineteen, Mam would be alive today. Nonsense, but Henrietta could be so convincing. My big sister who brought home those lovely babies for me to play with. And Agnella, what better little sister than Agnella, holding tight to my hand and smiling up at me as we walked the streets of Bridgeport. (“An aunt’s better than a sister,” she told me once, and then whispered, “and nicer than a mama.”) Agnella had entered the convent . . . and it would break her heart to know her mother was une connasse, as the French would say.

Jesse came in with the girls, carrying sandwiches and a big pot of tea, and set them on the parlor table. “I thought you’d have to stop talking long enough to eat. There’s ham and roast beef,” she said. And then to Henrietta, “I know you said to save this meat for you and Mr. Toot’s lunch, Mrs. Kelly, but . . .” She stopped.

“Fine, fine, Jesse,” Henrietta said.

Ann put a pile of plates and napkins next to the tray, and as we helped ourselves, I remembered all the parties at the flat on Hillock—aunts and uncles and cousins laughing. Mam, Granny Honora, dishing out plate after plate of colcannon, potatoes mashed with onions and cabbage running with butter, thick slices of beef and ham straight from the meatpacking houses.

Even after the boys moved on to better jobs, there was always someone we knew working in the stockyards to bring home the best cuts of meat. But Mam and Jim dying so close together changed everything, took the heart out of our house. Family parties were held at Uncle Steve’s—Ed’s father’s place—and we were the guests.

Did the other Kellys draw away from our family just a wee bit? Da dead so young and then Mam and Jim; Granny Honora, Aunt Máire and Uncle Patrick gone too, but they were long-lived. Was our family the hard luck Kellys? A widow, two spinsters, two bachelors. One brother had married and moved away. I had my work and Tim McShane. While Michael, Ann, Mart, and I had neither chick nor child, the other cousins had loads of children. Then the great burst of joy of Michael and Mame’s wedding and that wonderful party, until Tim McShane ruined the night and I . . . I closed my eyes and leaned against the back of the armchair.

Then suddenly, Rose was shaking me.

“I must’ve fallen asleep.”

“You must be exhausted,” she said.

I nodded. “Hard to sleep on the train.”

“Take a nap in our room, Aunt Nonie,” Ann said.

But Ed was standing up. “My mother has a room waiting for Nonie at our place,” he said. Aunt Nelly had been looking after Ed and his young son since Mary had died.

Rose walked over to John.

“Don’t leave, Aunt Rose. Don’t leave!” Mike said and the girls joined in, holding on to Rose’s hands, her dress, any part of her they could clutch.

“Stop that,” Henrietta said. “You’ll wake your mother. Quiet. No wonder she’s sick, with such ruffians running around this house.”

“That’s enough, Henrietta,” Michael said.

“I’m staying,” Rose said. “If that’s alright, Michael?”

“It’s not alright,” Henrietta broke in. “I’m not staying under the same roof as you, Rose McCabe. All of you scheming against me.”

And Michael woke up. Like that. In the snap of a finger. He stood up.

“Then go, Henrietta. You and Toots. Go back to Hillock with Mart and Ann. Now. Today.”

Then ructions!

Stella Lambert put down her mug of tea and got her Bobby, Mike, and the girls moving and out the door. “I’ll give them dinner,” she said.

We all just stared at Henrietta as she roared and raged until finally Toots took her by the arm. “Come on, Mother. We won’t stay where we’re not wanted.”

Never saw Michael so strong-faced and determined. “Get ready and I’ll drive you,” he said. Then to Rose, “You’ll explain to Mame? Tell her I’ll be back.”

“I’m sorry we dragged you home for this, Nonie,” John said as I got into Ed’s car. “But Rose said she just couldn’t face Henrietta alone and didn’t want to bring Ed into it on her own. Rose is not afraid of anybody, but Henrietta seems to have the kibosh on her.”

“On me too,” I said, “and believe me, the battle’s not over. Henrietta’s lost round one but she’ll come out fighting. I’m glad you’ll be staying here with Rose,” I said.

________

“Are you too tired for a quick stop on the way to my house, Nonie?” Ed asked me, as we turned off Archer Avenue onto a highway that was new to me. A very grand stretch of road going along the lake.

“I’m fine, Ed. What’s this avenue?”

“South Shore Drive,” Ed said.

“Your dream come true.”

Ed had been talking about building just such a highway since he was fourteen. “This is only the beginning,” he said to me. “Close your eyes, Nonie,” he said.

In a few minutes he stopped the car. “Look up,” he said. There above us on a rise, twenty or thirty white columns marched against the sky.

“Dear God,” I said. “It looks like a Roman temple.”

“Not Roman,” Ed said. “Greek. Those are Doric columns.”

“So tall,” I said.

“Each one’s a hundred and fifty feet high,” Ed said. “That’s fifteen stories.

And there’s another colonnade just like it on the east entrance and this is just the façade. There’s ten acres down below that are being made into the best stadium in the country. The field will be a half a mile long with three tracks going around. There’ll be seating for one hundred thousand.

We’ve already had inquiries from people who want to hold events here. Things like championship fights. The cardinal called me about having the Eucharistic Congress here. It’s going to be a gathering place for the entire city of Chicago. It’s not coming cheap. Probably going to cost ten million dollars, but there’s fifteen thousand jobs in the project and can you imagine the money that’s going to come into the city from all the events. It’ll be like the Columbian Exposition all over again.”

He pointed toward Lake Michigan. “I want to create an island and build museums and parks.”

“Wonderful, Ed.”

“With Thompson gone anything is possible. Private money is available and tourists are coming back to the city.”

There was honking behind us. A line of trucks trying to get to the construction site. Ed pulled out of their way back onto the drive. I tried to listen as we drove south but my eyes got heavy. I woke to find we were parked in front of a mansion.

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph! Where are we?” I asked.

“Mary and I bought this house right before she got sick. We wanted room for our children.”

“But it must have cost a fortune,” I said. “How . . .”

“I’ve worked hard,” Ed said, “and been lucky in my investments. Got some good stock tips.”

“But,” I began. Ed was getting out of the car. He came around, opened my door. Subject closed.

Yes, I thought, as we walked into the three-story redbrick house, set back from Ellis in the nicest part of Hyde Park. There should be loads of kids running in and out of the place, bringing their friends. Instead I found room after room sparsely furnished—no carpets, no curtains—and Aunt Nelly, Ed’s mother, in the kitchen serving liver and dumplings to a six-year-old boy. Ed’s son . . . Ed Junior.

She hugged me, this woman who’d known them all—Granny Honora, Aunt Máire, Uncle Patrick, my da and mam, all of home in her embrace, and that’s what she said to me.

“Welcome home, Nonie.”

“I’m too tired to eat,” I told her, and she took me upstairs and gave me one of her own nightgowns. A soft white tent of cotton. Comforting. “Thank you, Aunt Nelly.”

“Ed will bring your bag in from the car. You can unpack tomorrow.” No questions. No chat. But then Aunt Nelly’s half German. Nice that, sometimes.

I turned on my side, feather pillows under my head. Closed my eyes and then, as I did every night, I visited that part of my mind where Peter Keeley waited. The man I’d fallen in love with in Paris. Sometimes we were in the library of the Irish College, near the Pantheon, and he was translating the skirl of letters in an old Irish manuscript. So intense, as he opened my heritage to me. Or we were sharing our bed in my room overlooking the Place des Vosges. Tonight I found him in Connemara, on the shores of Lough Inagh, coming toward me. But then. Stop. Stay there. I couldn’t let my mind rush ahead to that freezing night just before Christmas when Cyril Peterson arrived with news from Ireland. The worst. Peter was dead. Killed in the civil war that had broken out just as Ireland had finally gotten Britain to withdraw. Former comrades shooting each other. No. Go back, go back. Imagine Peter smiling. Run to him.

I fell asleep with Aunt Nelly’s nightgown wrapping me. Chicago. Welcome home.

Copyright © 2019

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Have downloaded ‘irish above all’ and it’ a page-turner!

Nora’s adaptability and inventiveness continue from ‘Of Irish

Blood’ , managing by her wits, creativity and amazing ability to read situations and land on her feet in the most ‘happening’ of circumstances. Besides the intrinsic irish story, and wonderful tidbits of historical and other lore, ‘Irish above All’ also gives a great overview of life in America, its politics at local & municipal levels, circling out into the larger America. This is quite fascinating for those of us readers who were not raised in America. I’m still reading and loving every minute of this inspired/inspiring writing. Thank you, author MARY PAT KELLY!