Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Way of Kings, the first book in Brandon Sanderson’s sweeping epic fantasy series The Stormlight Archive. The third book in the series, Oathbringer, will be available November 14th – if you’re already caught up, you can start reading the first chapters here!

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Way of Kings, the first book in Brandon Sanderson’s sweeping epic fantasy series The Stormlight Archive. The third book in the series, Oathbringer, will be available November 14th – if you’re already caught up, you can start reading the first chapters here!

Roshar is a world of stone and storms. Uncanny tempests of incredible power sweep across the rocky terrain so frequently that they have shaped ecology and civilization alike. Animals hide in shells, trees pull in branches, and grass retracts into the soilless ground. Cities are built only where the topography offers shelter.

It has been centuries since the fall of the ten consecrated orders known as the Knights Radiant, but their Shardblades and Shardplate remain: mystical swords and suits of armor that transform ordinary men into near-invincible warriors. Men trade kingdoms for Shardblades. Wars were fought for them, and won by them.

One such war rages on a ruined landscape called the Shattered Plains. There, Kaladin, who traded his medical apprenticeship for a spear to protect his little brother, has been reduced to slavery. In a war that makes no sense, where ten armies fight separately against a single foe, he struggles to save his men and to fathom the leaders who consider them expendable.

Brightlord Dalinar Kholin commands one of those other armies. Like his brother, the late king, he is fascinated by an ancient text called The Way of Kings. Troubled by over-powering visions of ancient times and the Knights Radiant, he has begun to doubt his own sanity.

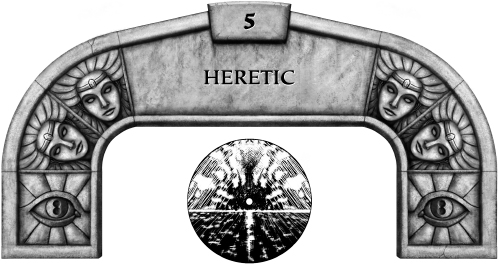

Across the ocean, an untried young woman named Shallan seeks to train under an eminent scholar and notorious heretic, Dalinar’s niece, Jasnah. Though she genuinely loves learning, Shallan’s motives are less than pure. As she plans a daring theft, her research for Jasnah hints at secrets of the Knights Radiant and the true cause of the war.

“You’ve killed me. Bastards, you’ve killed me! While the sun is still hot, I die!”

Collected on the fifth day of the week Chach of the month Betab of the year 1171, ten seconds before death. Subject was a darkeyed soldier thirty-one years of age. Sample is considered questionable.

FIVE YEARS LATER

I’m going to die, aren’t I?” Cenn asked.

The weathered veteran beside Cenn turned and inspected him. The veteran wore a full beard, cut short. At the sides, the black hairs were starting to give way to grey.

I’m going to die, Cenn thought, clutching his spear—the shaft slick with sweat. I’m going to die. Oh, Stormfather. I’m going to die. …

“How old are you, son?” the veteran asked. Cenn didn’t remember the man’s name. It was hard to recall anything while watching that other army form lines across the rocky battlefield. That lining up seemed so civil. Neat, organized. Shortspears in the front ranks, longspears and javelins next, archers at the sides. The darkeyed spearmen wore equipment like Cenn’s: leather jerkin and knee-length skirt with a simple steel cap and a matching breastplate.

Many of the lighteyes had full suits of armor. They sat astride horses, their honor guards clustering around them with breastplates that gleamed burgundy and deep forest green. Were there Shardbearers among them? Brightlord Amaram wasn’t a Shardbearer. Were any of his men? What if Cenn had to fight one? Ordinary men didn’t kill Shardbearers. It had happened so infrequently that each occurrence was now legendary.

It’s really happening, he thought with mounting terror. This wasn’t a drill in the camp. This wasn’t training out in the fields, swinging sticks. This was real. Facing that fact—his heart pounding like a frightened animal in his chest, his legs unsteady—Cenn suddenly realized that he was a coward. He shouldn’t have left the herds! He should never have—

“Son?” the veteran said, voice firm. “How old are you?”

“Fifteen, sir.”

“And what’s your name?”

“Cenn, sir.”

The mountainous, bearded man nodded. “I’m Dallet.”

“Dallet,” Cenn repeated, still staring out at the other army. There were so many of them! Thousands. “I’m going to die, aren’t I?”

“No.” Dallet had a gruff voice, but somehow that was comforting. “You’re going to be just fine. Keep your head on straight. Stay with the squad.”

“But I’ve barely had three months’ training!” He swore he could hear faint clangs from the enemy’s armor or shields. “I can barely hold this spear! Stormfather, I’m dead. I can’t—”

“Son,” Dallet interrupted, soft but firm. He raised a hand and placed it on Cenn’s shoulder. The rim of Dallet’s large round shield reflected the light from where it hung on his back. “You are going to be fine.”

“How can you know?” It came out as a plea.

“Because, lad. You’re in Kaladin Stormblessed’s squad.” The other soldiers nearby nodded in agreement.

Behind them, waves and waves of soldiers were lining up—thousands of them. Cenn was right at the front, with Kaladin’s squad of about thirty other men. Why had Cenn been moved to a new squad at the last moment? It had something to do with camp politics.

Why was this squad at the very front, where casualties were bound to be the greatest? Small fearspren—like globs of purplish goo—began to climb up out of the ground and gather around his feet. In a moment of sheer panic, he nearly dropped his spear and scrambled away. Dallet’s hand tightened on his shoulder. Looking up into Dallet’s confident black eyes, Cenn hesitated.

“Did you piss before we formed ranks?” Dallet asked.

“I didn’t have time to—”

“Go now.”

“Here?”

“If you don’t, you’ll end up with it running down your leg in battle, distracting you, maybe killing you. Do it.”

Embarrassed, Cenn handed Dallet his spear and relieved himself onto the stones. When he finished, he shot glances at those next to him. None of Kaladin’s soldiers smirked. They stood steady, spears to their sides, shields on their backs.

The enemy army was almost finished. The field between the two forces was bare, flat slickrock, remarkably even and smooth, broken only by occasional rockbuds. It would have made a good pasture. The warm wind blew in Cenn’s face, thick with the watery scents of last night’s highstorm.

“Dallet!” a voice said.

A man walked up through the ranks, carrying a shortspear that had two leather knife sheaths strapped to the haft. The newcomer was a young man—perhaps four years older than Cenn’s fifteen—but he was taller by several fingers than even Dallet. He wore the common leathers of a spearman, but under them was a pair of dark trousers. That wasn’t supposed to be allowed.

His black Alethi hair was shoulder-length and wavy, his eyes a dark brown. He also had knots of white cord on the shoulders of his jerkin, marking him as a squadleader.

The thirty men around Cenn snapped to attention, raising their spears in salute. This is Kaladin Stormblessed? Cenn thought incredulously. This youth?

“Dallet, we’re soon going to have a new recruit,” Kaladin said. He had a strong voice. “I need you to …” He trailed off as he noticed Cenn.

“He found his way here just a few minutes ago, sir,” Dallet said with a smile. “I’ve been gettin’ him ready.”

“Well done,” Kaladin said. “I paid good money to get that boy away from Gare. That man’s so incompetent he might as well be fighting for the other side.”

What? Cenn thought. Why would anyone pay to get me?

“What do you think about the field?” Kaladin asked. Several of the other spearmen nearby raised hands to shade from the sun, scanning the rocks.

“That dip next to the two boulders on the far right?” Dallet asked.

Kaladin shook his head. “Footing’s too rough.”

“Aye. Perhaps it is. What about the short hill over there? Far enough to avoid the first fall, close enough to not get too far ahead.”

Kaladin nodded, though Cenn couldn’t see what they were looking at. “Looks good.”

“The rest of you louts hear that?” Dallet shouted.

The men raised their spears high.

“Keep an eye on the new boy, Dallet,” Kaladin said. “He won’t know the signs.”

“Of course,” Dallet said, smiling. Smiling! How could the man smile? The enemy army was blowing horns. Did that mean they were ready? Even though Cenn had just relieved himself, he felt a trickle of urine run down his leg.

“Stay firm,” Kaladin said, then trotted down the front line to talk to the next squadleader over. Behind Cenn and the others, the dozens of ranks were still growing. The archers on the sides prepared to fire.

“Don’t worry, son,” Dallet said. “We’ll be fine. Squadleader Kaladin is lucky.”

The soldier on the other side of Cenn nodded. He was a lanky, red-haired Veden, with darker tan skin than the Alethi. Why was he fighting in an Alethi army? “That’s right. Kaladin, he’s stormblessed, right sure he is. We only lost … what, one man last battle?”

“But someone did die,” Cenn said.

Dallet shrugged. “People always die. Our squad loses the fewest. You’ll see.”

Kaladin finished conferring with the other squadleader, then jogged back to his team. Though he carried a shortspear—meant to be wielded one-handed with a shield in the other hand—his was a hand longer than those held by the other men.

“At the ready, men!” Dallet called. Unlike the other squad leaders, Kaladin didn’t fall into rank, but stood out in front of his squad.

The men around Cenn shuffled, excited. The sounds were repeated through the vast army, the stillness giving way before eagerness. Hundreds of feet shuffling, shields slapping, clasps clanking. Kaladin remained motionless, staring down the other army. “Steady, men,” he said without turning.

Behind, a lighteyed officer passed on horseback. “Be ready to fight! I want their blood, men. Fight and kill!”

“Steady,” Kaladin said again, after the man passed.

“Be ready to run,” Dallet said to Cenn.

“Run? But we’ve been trained to march in formation! To stay in our line!”

“Sure,” Dallet said. “But most of the men don’t have much more training than you. Those who can fight well end up getting sent to the Shattered Plains to battle the Parshendi. Kaladin’s trying to get us into shape to go there, to fight for the king.” Dallet nodded down the line. “Most of these here will break and charge; the lighteyes aren’t good enough commanders to keep them in formation. So stay with us and run.”

“Should I have my shield out?” Around Kaladin’s team, the other ranks were unhooking their shields. But Kaladin’s squad left their shields on their backs.

Before Dallet could answer, a horn blew from behind.

“Go!” Dallet said.

Cenn didn’t have much choice. The entire army started moving in a clamor of marching boots. As Dallet had predicted, the steady march didn’t last long. Some men began yelling, the roar taken up by others. Lighteyes called for them to go, run, fight. The line disintegrated.

As soon as that happened, Kaladin’s squad broke into a dash, running out into the front at full speed. Cenn scrambled to keep up, panicked and terrified. The ground wasn’t as smooth as it had seemed, and he nearly tripped on a hidden rockbud, vines withdrawn into its shell.

He righted himself and kept going, holding his spear in one hand, his shield clapping against his back. The distant army was in motion as well, their soldiers charging down the field. There was no semblance of a battle formation or a careful line. This wasn’t anything like the training had claimed it would be.

Cenn didn’t even know who the enemy was. A landlord was encroaching on Brightlord Amaram’s territory—the land owned, ultimately, by Highprince Sadeas. It was a border skirmish, and Cenn thought it was with another Alethi princedom. Why were they fighting each other? Perhaps the king would have put a stop to it, but he was on the Shattered Plains, seeking vengeance for the murder of King Gavilar five years before.

The enemy had a lot of archers. Cenn’s panic climbed to a peak as the first wave of arrows flew into the air. He stumbled again, itching to take out his shield. But Dallet grabbed his arm and yanked him forward.

Hundreds of arrows split the sky, dimming the sun. They arced and fell, dropping like skyeels upon their prey. Amaram’s soldiers raised shields. But not Kaladin’s squad. No shields for them.

Cenn screamed.

And the arrows slammed into the middle ranks of Amaram’s army, behind him. Cenn glanced over his shoulder, still running. The arrows fell behind him. Soldiers screamed, arrows broke against shields; only a few straggling arrows landed anywhere near the front ranks.

“Why?” he yelled at Dallet. “How did you know?”

“They want the arrows to hit where the men are most crowded,” the large man replied. “Where they’ll have the greatest chance of finding a body.”

Several other groups in the van left their shields lowered, but most ran awkwardly with their shields angled up to the sky, worried about arrows that wouldn’t hit them. That slowed them, and they risked getting trampled by the men behind who were getting hit. Cenn itched to raise his shield anyway; it felt so wrong to run without it.

The second volley hit, and men screamed in pain. Kaladin’s squad barreled toward the enemy soldiers, some of whom were dying to arrows from Amaram’s archers. Cenn could hear the enemy soldiers bellowing war cries, could make out individual faces. Suddenly, Kaladin’s squad pulled to a halt, forming a tight group. They’d reached the small incline that Kaladin and Dallet had chosen earlier.

Dallet grabbed Cenn and shoved him to the very center of the formation. Kaladin’s men lowered spears, pulling out shields as the enemy bore down on them. The charging foe used no careful formation; they didn’t keep the ranks of longspears in back and shortspears in front. They all just ran forward, yelling in a frenzy.

Cenn scrambled to get his shield unlatched from his back. Clashing spears rang in the air as squads engaged one another. A group of enemy spearmen rushed up to Kaladin’s squad, perhaps coveting the higher ground. The three dozen attackers had some cohesion, though they weren’t in as tight a formation as Kaladin’s squad was.

The enemy seemed determined to make up for it in passion; they bellowed and screamed in fury, rushing Kaladin’s line. Kaladin’s team held rank, defending Cenn as if he were some lighteyes and they were his honor guard. The two forces met with a crash of metal on wood, shields slamming together. Cenn cringed back.

It was over in a few eyeblinks. The enemy squad pulled back, leaving two dead on the stone. Kaladin’s team hadn’t lost anyone. They held their bristling V formation, though one man stepped back and pulled out a bandage to wrap a thigh wound. The rest of the men closed in to fill the spot. The wounded man was hulking and thick-armed; he cursed, but the wound didn’t look bad. He was on his feet in a moment, but didn’t return to the place where he’d been. Instead, he moved down to one end of the V formation, a more protected spot.

The battlefield was chaos. The two armies mingled indistinguishably; sounds of clanging, crunching, and screaming churned in the air. Many of the squads broke apart, members rushing from one encounter to another. They moved like hunters, groups of three or four seeking lone individuals, then brutally falling on them.

Kaladin’s team held its ground, engaging only enemy squads that got too close. Was this what a battle really was? Cenn’s practice had trained him for long ranks of men, shoulder to shoulder. Not this frenzied intermixing, this brutal pandemonium. Why didn’t more hold formation?

The real soldiers are all gone, Cenn thought. Off fighting in a real battle at the Shattered Plains. No wonder Kaladin wants to get his squad there.

Spears flashed on all sides; it was difficult to tell friend from foe, despite the emblems on breastplates and colored paint on shields. The battlefield broke down into hundreds of small groups, like a thousand different wars happening at the same time.

After the first few exchanges, Dallet took Cenn by the shoulder and placed him in the rank at the very bottom of the V pattern. Cenn, however, was worthless. When Kaladin’s team engaged enemy squads, all of his training fled him. It took everything he had to just remain there, holding his spear outward and trying to look threatening.

For the better part of an hour, Kaladin’s squad held their small hill, working as a team, shoulder to shoulder. Kaladin often left his position at the front, rushing this way and that, banging his spear on his shield in a strange rhythm.

Those are signals, Cenn realized as Kaladin’s squad moved from the V shape into a ring. With the screams of the dying and the thousands of men calling to others, it was nearly impossible to hear a single person’s voice. But the sharp clang of the spear against the metal plate on Kaladin’s shield was clear. Each time they changed formations, Dallet grabbed Cenn by the shoulder and steered him.

Kaladin’s team didn’t chase down stragglers. They remained on the defensive. And, while several of the men in Kaladin’s team took wounds, none of them fell. Their squad was too intimidating for the smaller groups, and larger enemy units retreated after a few exchanges, seeking easier foes.

Eventually something changed. Kaladin turned, watching the tides of the battle with discerning brown eyes. He raised his spear and smacked his shield in a quick rhythm he hadn’t used before. Dallet grabbed Cenn by the arm and pulled him away from the small hill. Why abandon it now?

Just then, the larger body of Amaram’s force broke, the men scattering. Cenn hadn’t realized how poorly the battle in this quarter had been going for his side. As Kaladin’s team retreated, they passed many wounded and dying, and Cenn grew nauseated. Soldiers were sliced open, their insides spilling out.

He didn’t have time for horror; the retreat quickly turned into a rout. Dallet cursed, and Kaladin beat his shield again. The squad changed direction, heading eastward. There, Cenn saw, a larger group of Amaram’s soldiers was holding.

But the enemy had seen the ranks break, and that made them bold. They rushed forward in clusters, like wild axehounds hunting stray hogs. Before Kaladin’s team was halfway across the field of dead and dying, a large group of enemy soldiers intercepted them. Kaladin reluctantly banged his shield; his squad slowed.

Cenn felt his heart begin to thump faster and faster. Nearby, a squad of Amaram’s soldiers was consumed; men stumbled and fell, screaming, trying to get away. The enemies used their spears like skewers, killing men on the ground like cremlings.

Kaladin’s men met the enemy in a crash of spears and shields. Bodies shoved on all sides, and Cenn was spun about. In the jumble of friend and foe, dying and killing, Cenn grew overwhelmed. So many men running in so many directions!

He panicked, scrambling for safety. A group of soldiers nearby wore Alethi uniforms. Kaladin’s squad. Cenn ran for them, but when some turned toward him, Cenn was terrified to realize he didn’t recognize them. This wasn’t Kaladin’s squad, but a small group of unfamiliar soldiers holding an uneven, broken line. Wounded and terrified, they scattered as soon as an enemy squad got close.

Cenn froze, holding his spear in a sweaty hand. The enemy soldiers charged right for him. His instincts urged him to flee, yet he had seen so many men picked off one at a time. He had to stand! He had to face them! He couldn’t run, he couldn’t—

He yelled, stabbing his spear at the lead soldier. The man casually knocked the weapon aside with his shield, then drove his shortspear into Cenn’s thigh. The pain was hot, so hot that the blood squirting out on his leg felt cold by comparison. Cenn gasped.

The soldier yanked the weapon free. Cenn stumbled backward, dropping his spear and shield. He fell to the rocky ground, splashing in someone else’s blood. His foe raised a spear high, a looming silhouette against the stark blue sky, ready to ram it into Cenn’s heart.

And then he was there.

Squadleader. Stormblessed. Kaladin’s spear came as if out of nowhere, narrowly deflecting the blow that was to have killed Cenn. Kaladin set himself in front of Cenn, alone, facing down six spearmen. He didn’t flinch. He charged.

It happened so quickly. Kaladin swept the feet from beneath the man who had stabbed Cenn. Even as that man fell, Kaladin reached up and flipped a knife from one of the sheaths tied about his spear. His hand snapped, knife flashing and hitting the thigh of a second foe. That man fell to one knee, screaming.

A third man froze, looking at his fallen allies. Kaladin shoved past a wounded enemy and slammed his spear into the gut of the third man. A fourth man fell with a knife to the eye. When had Kaladin grabbed that knife? He spun between the last two, his spear a blur, wielding it like a quarterstaff. For a moment, Cenn thought he could see something surrounding the squadleader. A warping of the air, like the wind itself become visible.

I’ve lost a lot of blood. It’s flowing out so quickly. …

Kaladin spun, knocking aside attacks, and the last two spearmen fell with gurgles that Cenn thought sounded surprised. Foes all down, Kaladin turned and knelt beside Cenn. The squadleader set aside his spear and whipped a white strip of cloth from his pocket, then efficiently wrapped it tight around Cenn’s leg. Kaladin worked with the ease of one who had bound wounds dozens of times before.

“Kaladin, sir!” Cenn said, pointing at one of the soldiers Kaladin had wounded. The enemy man held his leg as he stumbled to his feet. In a second, however, mountainous Dallet was there, shoving the foe with his shield. Dallet didn’t kill the wounded man, but let him stumble away, unarmed.

The rest of the squad arrived and formed a ring around Kaladin, Dallet, and Cenn. Kaladin stood up, raising his spear to his shoulder; Dallet handed him back his knives, retrieved from the fallen foes.

“Had me worried there, sir,” Dallet said. “Running off like that.”

“I knew you’d follow,” Kaladin said. “Raise the red banner. Cyn, Korater, you’re going back with the boy. Dallet, hold here. Amaram’s line is bulging in this direction. We should be safe soon.”

“And you, sir?” Dallet asked.

Kaladin looked across the field. A pocket had opened in the enemy forces, and a man rode there on a white horse, swinging about him with a wicked mace. He wore full plate armor, polished and gleaming silver.

“A Shardbearer,” Cenn said.

Dallet snorted. “No, thank the Stormfather. Just a lighteyed officer. Shardbearers are far too valuable to waste on a minor border dispute.”

Kaladin watched the lighteyes with a seething hatred. It was the same hatred Cenn’s father had shown when he’d spoken of chull rustlers, or the hatred Cenn’s mother would display when someone mentioned Kusiri, who had run off with the cobbler’s son.

“Sir?” Dallet said hesitantly.

“Subsquads Two and Three, pincer pattern,” Kaladin said, his voice hard. “We’re taking a brightlord off his throne.”

“You sure that’s wise, sir? We’ve got wounded.”

Kaladin turned toward Dallet. “That’s one of Hallaw’s officers. He might be the one.”

“You don’t know that, sir.”

“Regardless, he’s a battalionlord. If we kill an officer that high, we’re all but guaranteed to be in the next group sent to the Shattered Plains. We’re taking him.” His eyes grew distant. “Imagine it, Dallet. Real soldiers. A warcamp with discipline and lighteyes with integrity. A place where our fighting will mean something.”

Dallet sighed, but nodded. Kaladin waved to a group of his soldiers; then they raced across the field. A smaller group of soldiers, including Dallet, waited behind with the wounded. One of those—a thin man with black Alethi hair speckled with a handful of blond hairs, marking some foreign blood—pulled a long red ribbon from his pocket and attached it to his spear. He held the spear aloft, letting the ribbon flap in the wind.

“It’s a call for runners to carry our wounded off the field,” Dallet said to Cenn. “We’ll have you out of here soon. You were brave, standing against those six.”

“Fleeing seemed stupid,” Cenn said, trying to take his mind off his throbbing leg. “With so many wounded on the field, how can we think that the runners’ll come for us?”

“Squadleader Kaladin bribes them,” Dallet said. “They usually only carry off lighteyes, but there are more runners than there are wounded lighteyes. The squadleader puts most of his pay into the bribes.”

“This squad is different,” Cenn said, feeling light-headed.

“Told you.”

“Not because of luck. Because of training.”

“That’s part of it. Part of it is because we know if we get hurt, Kaladin will get us off the battlefield.” He paused, looking over his shoulder. As Kaladin had predicted, Amaram’s line was surging back, recovering.

The mounted enemy lighteyes from before was energetically laying about with his mace. A group of his honor guard moved to one side, engaging Kaladin’s subsquads. The lighteyes turned his horse. He wore an open-fronted helm that had sloping sides and a large set of plumes on the top. Cenn couldn’t make out his eye color, but he knew it would be blue or green, maybe yellow or light grey. He was a brightlord, chosen at birth by the Heralds, marked for rule.

He impassively regarded those who fought nearby. Then one of Kaladin’s knives took him in the right eye.

The brightlord screamed, falling back off the saddle as Kaladin somehow slipped through the lines and leaped upon him, spear raised.

“Aye, it’s part training,” Dallet said, shaking his head. “But it’s mostly him. He fights like a storm, that one, and thinks twice as fast as other men. The way he moves sometimes …”

“He bound my leg,” Cenn said, realizing he was beginning to speak nonsense due to the blood loss. Why point out the bound leg? It was a simple thing.

Dallet just nodded. “He knows a lot about wounds. He can read glyphs too. He’s a strange man, for a lowly darkeyed spearman, our squadleader is.” He turned to Cenn. “But you should save your strength, son. The squadleader won’t be pleased if we lose you, not after what he paid to get you.”

“Why?” Cenn asked. The battlefield was growing quieter, as if many of the dying men had already yelled themselves hoarse. Almost everyone around them was an ally, but Dallet still watched to make sure no enemy soldiers tried to strike at Kaladin’s wounded.

“Why, Dallet?” Cenn repeated, feeling urgent. “Why bring me into his squad? Why me?”

Dallet shook his head. “It’s just how he is. Hates the thought of young kids like you, barely trained, going to battle. Every now and again, he grabs one and brings him into his squad. A good half dozen of our men were once like you.” Dallet’s eyes got a far-off look. “I think you all remind him of someone.”

Cenn glanced at his leg. Painspren—like small orange hands with overly long fingers—were crawling around him, reacting to his agony. They began turning away, scurrying in other directions, seeking other wounded. His pain was fading, his leg—his whole body—feeling numb.

He leaned back, staring up at the sky. He could hear faint thunder. That was odd. The sky was cloudless.

Dallet cursed.

Cenn turned, shocked out of his stupor. Galloping directly toward them was a massive black horse bearing a rider in gleaming armor that seemed to radiate light. That armor was seamless—no chain underneath, just smaller plates, incredibly intricate. The figure wore an unornamented full helm, and the plate was gilded. He carried a massive sword in one hand, fully as long as a man was tall. It wasn’t a simple, straight sword—it was curved, and the side that wasn’t sharp was ridged, like flowing waves. Etchings covered its length.

It was beautiful. Like a work of art. Cenn had never seen a Shardbearer, but he knew immediately what this was. How could he ever have mistaken a simple armored lighteyes for one of these majestic creatures?

Hadn’t Dallet claimed there would be no Shardbearers on this battlefield? Dallet scrambled to his feet, calling for the subsquad to form up. Cenn just sat where he was. He couldn’t have stood, not with that leg wound.

He felt so light-headed. How much blood had he lost? He could barely think.

Either way, he couldn’t fight. You didn’t fight something like this. Sun gleamed against that plate armor. And that gorgeous, intricate, sinuous sword. It was like … like the Almighty himself had taken form to walk the battlefield.

And why would you want to fight the Almighty?

Cenn closed his eyes.

“Ten orders. We were loved, once. Why have you forsaken us, Almighty! Shard of my soul, where have you gone?”

Collected on the second day of Kakash, year 1171, five seconds before death. Subject was a lighteyed woman in her third decade.

EIGHT MONTHS LATER

Kaladin’s stomach growled as he reached through the bars and accepted the bowl of slop. He pulled the small bowl—more a cup—between the bars, sniffed it, then grimaced as the caged wagon began to roll again. The sludgy grey slop was made from overcooked tallow grain, and this batch was flecked with crusted bits of yesterday’s meal.

Revolting though it was, it was all he would get. He began to eat, legs hanging out between the bars, watching the scenery pass. The other slaves in his cage clutched their bowls protectively, afraid that someone might steal from them. One of them tried to steal Kaladin’s food on the first day. He’d nearly broken the man’s arm. Now everyone left him alone.

Suited him just fine.

He ate with his fingers, careless of the dirt. He’d stopped noticing dirt months ago. He hated that he felt some of that same paranoia that the others showed. How could he not, after eight months of beatings, deprivation, and brutality?

He fought down the paranoia. He wouldn’t become like them. Even if he’d given up everything else—even if all had been taken from him, even if there was no longer hope of escape. This one thing he would retain. He was a slave. But he didn’t need to think like one.

He finished the slop quickly. Nearby, one of the other slaves began to cough weakly. There were ten slaves in the wagon, all men, scraggly-bearded and dirty. It was one of three wagons in their caravan through the Unclaimed Hills.

The sun blazed reddish white on the horizon, like the hottest part of a smith’s fire. It lit the framing clouds with a spray of color, paint thrown carelessly on a canvas. Covered in tall, monotonously green grass, the hills seemed endless. On a nearby mound, a small figure flitted around the plants, dancing like a fluttering insect. The figure was amorphous, vaguely translucent. Windspren were devious spirits who had a penchant for staying where they weren’t wanted. He’d hoped that this one had gotten bored and left, but as Kaladin tried to toss his wooden bowl aside, he found that it stuck to his fingers.

The windspren laughed, zipping by, nothing more than a ribbon of light without form. He cursed, tugging on the bowl. Windspren often played pranks like that. He pried at the bowl, and it eventually came free. Grumbling, he tossed it to one of the other slaves. The man quickly began to lick at the remnants of the slop.

“Hey,” a voice whispered.

Kaladin looked to the side. A slave with dark skin and matted hair was crawling up to him, timid, as if expecting Kaladin to be angry. “You’re not like the others.” The slave’s black eyes glanced upward, toward Kaladin’s forehead, which bore three brands. The first two made a glyphpair, given to him eight months ago, on his last day in Amaram’s army. The third was fresh, given to him by his most recent master. Shash, the last glyph read. Dangerous.

The slave had his hand hidden behind his rags. A knife? No, that was ridiculous. None of these slaves could have hidden a weapon; the leaves hidden in Kaladin’s belt were as close as one could get. But old instincts could not be banished easily, so Kaladin watched that hand.

“I heard the guards talking,” the slave continued, shuffling a little closer. He had a twitch that made him blink too frequently. “You’ve tried to escape before, they said. You have escaped before.”

Kaladin made no reply.

“Look,” the slave said, moving his hand out from behind his rags and revealing his bowl of slop. It was half full. “Take me with you next time,” he whispered. “I’ll give you this. Half my food from now until we get away. Please.” As he spoke, he attracted a few hungerspren. They looked like brown flies that flitted around the man’s head, almost too small to see.

Kaladin turned away, looking out at the endless hills and their shifting, moving grasses. He rested one arm across the bars and placed his head against it, legs still hanging out.

“Well?” the slave asked.

“You’re an idiot. If you gave me half your food, you’d be too weak to escape if I were to flee. Which I won’t. It doesn’t work.”

“But—”

“Ten times,” Kaladin whispered. “Ten escape attempts in eight months, fleeing from five different masters. And how many of them worked?”

“Well … I mean … you’re still here. …”

Eight months. Eight months as a slave, eight months of slop and beatings. It might as well have been an eternity. He barely remembered the army anymore. “You can’t hide as a slave,” Kaladin said. “Not with that brand on your forehead. Oh, I got away a few times. But they always found me. And then back I went.”

Once, men had called him lucky. Stormblessed. Those had been lies—if anything, Kaladin had bad luck. Soldiers were a superstitious sort, and though he’d initially resisted that way of thinking, it was growing harder and harder. Every person he had ever tried to protect had ended up dead. Time and time again. And now, here he was, in an even worse situation than where he’d begun. It was better not to resist. This was his lot, and he was resigned to it.

There was a certain power in that, a freedom. The freedom of not having to care.

The slave eventually realized Kaladin wasn’t going to say anything further, and so he retreated, eating his slop. The wagons continued to roll, fields of green extending in all directions. The area around the rattling wagons was bare, however. When they approached, the grass pulled away, each individual stalk withdrawing into a pinprick hole in the stone. After the wagons moved on, the grass timidly poked back out and stretched its blades toward the air. And so, the cages moved along what appeared to be an open rock highway, cleared just for them.

This far into the Unclaimed Hills, the highstorms were incredibly powerful. The plants had learned to survive. That’s what you had to do, learn to survive. Brace yourself, weather the storm.

Kaladin caught a whiff of another sweaty, unwashed body and heard the sound of shuffling feet. He looked suspiciously to the side, expecting that same slave to be back.

It was a different man this time, though. He had a long black beard stuck with bits of food and snarled with dirt. Kaladin kept his own beard shorter, allowing Tvlakv’s mercenaries to hack it down periodically. Like Kaladin, the slave wore the remains of a brown sack tied with a rag, and he was dark-eyed, of course—perhaps a deep dark green, though with darkeyes it was hard to tell. They all looked brown or black unless you caught them in the right light.

The newcomer cringed away, raising his hands. He had a rash on one hand, the skin just faintly discolored. He’d likely approached because he’d seen Kaladin respond to that other man. The slaves had been frightened of him since the first day, but they were also obviously curious.

Kaladin sighed and turned away. The slave hesitantly sat down. “Mind if I ask how you became a slave, friend? Can’t help wondering. We’re all wondering.”

Judging by the accent and the dark hair, the man was Alethi, like Kaladin. Most of the slaves were. Kaladin didn’t reply to the question.

“Me, I stole a herd of chull,” the man said. He had a raspy voice, like sheets of paper rubbing together. “If I’d taken one chull, they might have just beaten me. But a whole herd. Seventeen head …” He chuckled to himself, admiring his own audacity.

In the far corner of the wagon, someone coughed again. They were a sorry lot, even for slaves. Weak, sickly, underfed. Some, like Kaladin, were repeat runaways—though Kaladin was the only one with a shash brand. They were the most worthless of a worthless caste, purchased at a steep discount. They were probably being taken for resale in a remote place where men were desperate for labor. There were plenty of small, independent cities along the coast of the Unclaimed Hills, places where Vorin rules governing the use of slaves were just a distant rumor.

Coming this way was dangerous. These lands were ruled by nobody, and by cutting across open land and staying away from established trade routes, Tvlakv could easily run afoul of unemployed mercenaries. Men who had no honor and no fear of slaughtering a slavemaster and his slaves in order to steal a few chulls and wagons.

Men who had no honor. Were there men who had honor?

No, Kaladin thought. Honor died eight months ago.

“So?” asked the scraggly-bearded man. “What did you do to get made a slave?”

Kaladin raised his arm against the bars again. “How did you get caught?”

“Odd thing, that,” the man said. Kaladin hadn’t answered his question, but he had replied. That seemed enough. “It was a woman, of course. Should have known she’d sell me.”

“Shouldn’t have stolen chulls. Too slow. Horses would have been better.”

The man laughed riotously. “Horses? What do you think me, a madman? If I’d been caught stealing those, I’d have been hanged. Chulls, at least, only earned me a slave’s brand.”

Kaladin glanced to the side. This man’s forehead brand was older than Kaladin’s, the skin around the scar faded to white. What was that glyphpair? “Sas morom,” Kaladin said. It was the highlord’s district where the man had originally been branded.

The man looked up with shock. “Hey! You know glyphs?” Several of the slaves nearby stirred at this oddity. “You must have an even better story than I thought, friend.”

Kaladin stared out over those grasses blowing in the mild breeze. Whenever the wind picked up, the more sensitive of the grass stalks shrank down into their burrows, leaving the landscape patchy, like the coat of a sickly horse. That windspren was still there, moving between patches of grass. How long had it been following him? At least a couple of months now. That was downright odd. Maybe it wasn’t the same one. They were impossible to tell apart.

“Well?” the man prodded. “Why are you here?”

“There are many reasons why I’m here,” Kaladin said. “Failures. Crimes. Betrayals. Probably the same for most every one of us.”

Around him, several of the men grunted in agreement; one of those grunts then degenerated into a hacking cough. Persistent coughing, a part of Kaladin’s mind thought, accompanied by an excess of phlegm and fevered mumbling at night. Sounds like the grindings.

“Well,” the talkative man said, “perhaps I should ask a different question. Be more specific, that’s what my mother always said. Say what you mean and ask for what you want. What’s the story of you getting that first brand of yours?”

Kaladin sat, feeling the wagon thump and roll beneath him. “I killed a lighteyes.”

His unnamed companion whistled again, this time even more appreciative than before. “I’m surprised they let you live.”

“Killing the lighteyes isn’t why I was made a slave,” Kaladin said. “It’s the one I didn’t kill that’s the problem.”

“How’s that?”

Kaladin shook his head, then stopped answering the talkative man’s questions. The man eventually wandered to the front of the wagon’s cage and sat down, staring at his bare feet.

##

Hours later, Kaladin still sat in his place, idly fingering the glyphs on his forehead. This was his life, day in and day out, riding in these cursed wagons.

His first brands had healed long ago, but the skin around the shash brand was red, irritated, and crusted with scabs. It throbbed, almost like a second heart. It hurt even worse than the burn had when he grabbed the heated handle of a cooking pot as a child.

Lessons drilled into Kaladin by his father whispered in the back of his brain, giving the proper way to care for a burn. Apply a salve to prevent infection, wash once daily. Those memories weren’t a comfort; they were an annoyance. He didn’t have fourleaf sap or lister’s oil; he didn’t even have water for the washing.

The parts of the wound that had scabbed over pulled at his skin, making his forehead feel tight. He could barely pass a few minutes without scrunching up his brow and irritating the wound. He’d grown accustomed to reaching up and wiping away the streaks of blood that trickled from the cracks; his right forearm was smeared with it. If he’d had a mirror, he could probably have spotted tiny red rotspren gathering around the wound.

The sun set in the west, but the wagons kept rolling. Violet Salas peeked over the horizon to the east, seeming hesitant at first, as if making sure the sun had vanished. It was a clear night, and the stars shivered high above. Taln’s Scar—a swath of deep red stars that stood out vibrantly from the twinkling white ones—was high in the sky this season.

That slave who’d been coughing earlier was at it again. A ragged, wet cough. Once, Kaladin would have been quick to go help, but something within him had changed. So many people he’d tried to help were now dead. It seemed to him—irrationally—that the man would be better off without his interference. After failing Tien, then Dallet and his team, then ten successive groups of slaves, it was hard to find the will to try again.

Two hours past First Moon, Tvlakv finally called a halt. His two brutish mercenaries climbed from their places atop their wagons, then moved to build a small fire. Lanky Taran—the serving boy—tended the chulls. The large crustaceans were nearly as big as wagons themselves. They settled down, pulling into their shells for the night with clawfuls of grain. Soon they were nothing more than three lumps in the darkness, barely distinguishable from boulders. Finally, Tvlakv began checking on the slaves one at a time, giving each a ladle of water, making certain his investments were healthy. Or, at least, as healthy as could be expected for this poor lot.

Tvlakv started with the first wagon, and Kaladin—still sitting—pushed his fingers into his makeshift belt, checking on the leaves he’d hidden there. They crackled satisfactorily, the stiff, dried husks rough against his skin. He still wasn’t certain what he was going to do with them. He’d grabbed them on a whim during one of the sessions when he’d been allowed out of the wagon to stretch his legs. He doubted anyone else in the caravan knew how to recognize blackbane—narrow leaves on a trefoil prong—so it hadn’t been too much of a risk.

Absently, he took the leaves out and rubbed them between forefinger and palm. They had to dry before reaching their potency. Why did he carry them? Did he mean to give them to Tvlakv and get revenge? Or were they a contingency, to be retained in case things got too bad, too unbearable?

Surely I haven’t fallen that far, he thought. It was just more likely his instinct of securing a weapon when he saw one, no matter how unusual. The landscape was dark. Salas was the smallest and dimmest of the moons, and while her violet coloring had inspired countless poets, she didn’t do much to help you see your hand in front of your face.

“Oh!” a soft, feminine voice said. “What’s that?”

A translucent figure—just a handspan tall—peeked up from over the edge of the floor near Kaladin. She climbed up and into the wagon, as if scaling some high plateau. The windspren had taken the shape of a young woman—larger spren could change shapes and sizes—with an angular face and long, flowing hair that faded into mist behind her head. She—Kaladin couldn’t help but think of the windspren as a she—was formed of pale blues and whites and wore a simple, flowing white dress of a girlish cut that came down to midcalf. Like the hair, it faded to mist at the very bottom. Her feet, hands, and face were crisply distinct, and she had the hips and bust of a slender woman.

Kaladin frowned at the spirit. Spren were all around; you just ignored them most of the time. But this one was an oddity. The windspren walked upward, as if climbing an invisible staircase. She reached a height where she could stare at Kaladin’s hand, so he closed his fingers around the black leaves. She walked around his fist in a circle. Although she glowed like an afterimage from looking at the sun, her form provided no real illumination.

She bent down, looking at his hand from different angles, like a child expecting to find a hidden piece of candy. “What is it?” Her voice was like a whisper. “You can show me. I won’t tell anyone. Is it a treasure? Have you cut off a piece of the night’s cloak and tucked it away? Is it the heart of a beetle, so tiny yet powerful?”

He said nothing, causing the spren to pout. She floated up, hovering though she had no wings, and looked him in the eyes. “Kaladin, why must you ignore me?”

Kaladin started. “What did you say?”

She smiled mischievously, then sprang away, her figure blurring into a long white ribbon of blue-white light. She shot between the bars—twisting and warping in the air, like a strip of cloth caught in the wind—and darted beneath the wagon.

“Storm you!” Kaladin said, leaping to his feet. “Spirit! What did you say? Repeat that!” Spren didn’t use people’s names. Spren weren’t intelligent. The larger ones—like windspren or riverspren—could mimic voices and expressions, but they didn’t actually think. They didn’t …

“Did any of you hear that?” Kaladin asked, turning to the cage’s other occupants. The roof was just high enough to let Kaladin stand. The others were lying back, waiting to get their ladle of water. He got no response beyond a few mutters to be quiet and some coughs from the sick man in the corner. Even Kaladin’s “friend” from earlier ignored him. The man had fallen into a stupor, staring at his feet, wiggling his toes periodically.

Maybe they hadn’t seen the spren. Many of the larger ones were invisible except to the person they were tormenting. Kaladin sat back down on the floor of the wagon, hanging his legs outside. The windspren had said his name, but undoubtedly she’d just repeated what she’d heard before. But … none of the men in the cage knew his name.

Maybe I’m going mad, Kaladin thought. Seeing things that aren’t there. Hearing voices.

He took a deep breath, then opened his hand. His grip had cracked and broken the leaves. He’d need to tuck them away to prevent further—

“Those leaves look interesting,” said that same feminine voice. “You like them a lot, don’t you?”

Kaladin jumped, twisting to the side. The windspren stood in the air just beside his head, white dress rippling in a wind Kaladin couldn’t feel.

“How do you know my name?” he demanded.

The windspren didn’t answer. She walked on air over to the bars, then poked her head out, watching Tvlakv the slaver administer drinks to the last few slaves in the first wagon. She looked back at Kaladin. “Why don’t you fight? You did before. Now you’ve stopped.”

“Why do you care, spirit?”

She cocked her head. “I don’t know,” she said, as if surprised at herself. “But I do. Isn’t that odd?”

It was more than odd. What did he make of a spren that not only used his name, but seemed to remember things he had done weeks ago?

“People don’t eat leaves, you know, Kaladin,” she said, folding translucent arms. Then she cocked her head. “Or do you? I can’t remember. You’re so strange, stuffing some things into your mouths, leaking out other things when you don’t think anyone is looking.”

“How do you know my name?” he whispered.

“How do you know it?”

“I know it because … because it’s mine. My parents told it to me. I don’t know.”

“Well I don’t either,” she said, nodding as if she’d just won some grand argument.

“Fine,” he said. “But why are you using my name?”

“Because it’s polite. And you are impolite.”

“Spren don’t know what that means!”

“See, there,” she said, pointing at him. “Impolite.”

Kaladin blinked. Well, he was far from where he’d grown up, walking foreign stone and eating foreign food. Perhaps the spren who lived here were different from those back home.

“So why don’t you fight?” she asked, flitting down to rest on his legs, looking up at his face. She had no weight that he could feel.

“I can’t fight,” he said softly.

“You did before.”

He closed his eyes and rested his head forward against the bars. “I’m so tired.” He didn’t mean the physical fatigue, though eight months eating leftovers had stolen much of the lean strength he’d cultivated while at war. He felt tired. Even when he got enough sleep. Even on those rare days when he wasn’t hungry, cold, or stiff from a beating. So tired …

“You have been tired before.”

“I’ve failed, spirit,” he replied, squeezing his eyes shut. “Must you torment me so?”

They were all dead. Cenn and Dallet, and before that Tukks and the Takers. Before that, Tien. Before that, blood on his hands and the corpse of a young girl with pale skin.

Some of the slaves nearby muttered, likely thinking he was mad. Anyone could end up drawing a spren, but you learned early that talking to one was pointless. Was he mad? Perhaps he should wish for that—madness was an escape from the pain. Instead, it terrified him.

He opened his eyes. Tvlakv was finally waddling up to Kaladin’s wagon with his bucket of water. The portly, brown-eyed man walked with a very faint limp; the result of a broken leg, perhaps. He was Thaylen, and all Thaylen men had the same stark white beards—regardless of their age or the color of the hair on their heads—and white eyebrows. Those eyebrows grew very long, and the Thaylen wore them pushed back over the ears. That made him appear to have two white streaks in his otherwise black hair.

His clothing—striped trousers of black and red with a dark blue sweater that matched the color of his knit cap—had once been fine, but it was now growing ragged. Had he once been something other than a slaver? This life—the casual buying and selling of human flesh—seemed to have an effect on men. It wearied the soul, even if it did fill one’s money pouch.

Tvlakv kept his distance from Kaladin, carrying his oil lantern over to inspect the coughing slave at the front of the cage. Tvlakv called to his mercenaries. Bluth—Kaladin didn’t know why he’d bothered to learn their names—wandered over. Tvlakv spoke quietly, pointing at the slave. Bluth nodded, slab-like face shadowed in the lanternlight, and pulled the cudgel free from his belt.

The windspren took the form of a white ribbon, then zipped over toward the sick man. She spun and twisted a few times before landing on the floor, becoming a girl again. She leaned in to inspect the man. Like a curious child.

Kaladin turned away and closed his eyes, but he could still hear the coughing. Inside his mind, his father’s voice responded. To cure the grinding coughs, said the careful, precise tone, administer two handfuls of bloodivy, crushed to a powder, each day. If you don’t have that, be certain to give the patient plenty of liquids, preferably with sugar stirred in. As long as the patient stays hydrated, he will most likely survive. The disease sounds far worse than it is.

Most likely survive …

Those coughs continued. Someone unlatched the cage door. Would they know how to help the man? Such an easy solution. Give him water, and he would live.

It didn’t matter. Best not to get involved.

Men dying on the battlefield. A youthful face, so familiar and dear, looking to Kaladin for salvation. A sword wound slicing open the side of a neck. A Shardbearer charging through Amaram’s ranks.

Blood. Death. Failure. Pain.

And his father’s voice. Can you really leave him, son? Let him die when you could have helped?

Storm it!

“Stop!” Kaladin yelled, standing.

The other slaves scrambled back. Bluth jumped up, slamming the cage door closed and holding up his cudgel. Tvlakv shied behind the mercenary, using him as cover.

Kaladin took a deep breath, closing his hand around the leaves and then raising the other to his head, wiping away a smear of blood. He crossed the small cage, bare feet thumping on the wood. Bluth glared as Kaladin knelt beside the sick man. The flickering light illuminated a long, drawn face and nearly bloodless lips. The man had coughed up phlegm; it was greenish and solid. Kaladin felt the man’s neck for swelling, then checked his dark brown eyes.

“It’s called the grinding coughs,” Kaladin said. “He will live, if you give him an extra ladle of water every two hours for five days or so. You’ll have to force it down his throat. Mix in sugar, if you have any.”

Bluth scratched at his ample chin, then glanced at the shorter slaver.

“Pull him out,” Tvlakv said.

The wounded slave awoke as Bluth unlocked the cage. The mercenary waved Kaladin back with his cudgel, and Kaladin reluctantly withdrew. After putting away his cudgel, Bluth grabbed the slave under the arms and dragged him out, all the while trying to keep a nervous eye on Kaladin. Kaladin’s last failed escape attempt had involved twenty armed slaves. His master should have executed him for that, but he had claimed Kaladin was “intriguing” and branded him with shash, then sold him for a pittance.

There always seemed to be a reason Kaladin survived when those he’d tried to help died. Some men might have seen that as a blessing, but he saw it as an ironic kind of torment. He’d spent some time under his previous master speaking with a slave from the West, a Selay man who had spoken of the Old Magic from their legends and its ability to curse people. Could that be what was happening to Kaladin?

Don’t be foolish, he told himself.

The cage door snapped back in place, locking. The cages were necessary—Tvlakv had to protect his fragile investment from the highstorms. The cages had wooden sides that could be pulled up and locked into place during the furious gales.

Bluth dragged the slave over to the fire, beside the unpacked water barrel. Kaladin felt himself relax. There, he told himself. Perhaps you can still help. Perhaps there’s a reason to care.

Kaladin opened his hand and looked down at the crumbled black leaves in his palm. He didn’t need these. Sneaking them into Tvlakv’s drink would not only be difficult, but pointless. Did he really want the slaver dead? What would that accomplish?

A low crack rang in the air, followed by a second one, duller, like someone dropping a bag of grain. Kaladin snapped his head up, looking to where Bluth had deposited the sick slave. The mercenary raised his cudgel one more time, then snapped it down, the weapon making a cracking sound as it hit the slave’s skull.

The slave hadn’t uttered a cry of pain or protest. His corpse slumped over in the darkness; Bluth casually picked it up and slung it over his shoulder.

“No!” Kaladin yelled, leaping across the cage and slamming his hands against the bars.

Tvlakv stood warming himself by the fire.

“Storm you!” Kaladin screamed. “He could have lived, you bastard!”

Tvlakv glanced at him. Then, leisurely, the slaver walked over, straightening his deep blue knit cap. “He would have gotten you all sick, you see.” His voice was lightly accented, smashing words together, not giving the proper syllables emphasis. Thaylens always sounded to Kaladin like they were mumbling. “I would not lose an entire wagon for one man.”

“He’s past the spreading stage!” Kaladin said, slamming his hands against the bars again. “If any of us were going to catch it, we’d have done so by now.”

“Hope that you don’t. I think he was past saving.”

“I told you otherwise!”

“And I should believe you, deserter?” Tvlakv said, amused. “A man with eyes that smolder and hate? You would kill me.” He shrugged. “I care not. So long as you are strong when it is time for sales. You should bless me for saving you from that man’s sickness.”

“I’ll bless your cairn when I pile it up myself,” Kaladin replied.

Tvlakv smiled, walking back toward the fire. “Keep that fury, deserter, and that strength. It will pay me well on our arrival.”

Not if you don’t live that long, Kaladin thought. Tvlakv always warmed the last of the water from the bucket he used for the slaves. He’d make himself tea from it, hanging it over the fire. If Kaladin made sure he was watered last, then powdered the leaves and dropped them into the—

Kaladin froze, then looked down at his hands. In his haste, he’d forgotten that he’d been holding the blackbane. He’d dropped the flakes as he slammed his hands against the bars. Only a few bits stuck to his palms, not enough to be potent.

He spun to look backward; the floor of the cage was dirty and covered with grime. If the flakes had fallen there, there was no way to collect them. The wind gathered suddenly, blowing dust, crumbs, and dirt out of the wagon and into the night.

Even in this, Kaladin failed.

He sank down, his back to the bars, and bowed his head. Defeated. That cursed windspren kept darting around him, looking confused.

“A man stood on a cliffside and watched his homeland fall into dust. The waters surged beneath, so far beneath. And he heard a child crying. They were his own tears.”

Collected on the 4th of Tanates, year 1171, thirty seconds before death. Subject was a cobbler of some renown.

Kharbranth, City of Bells, was not a place that Shallan had ever imagined she would visit. Though she’d often dreamed of traveling, she’d expected to spend her early life sequestered in her family’s manor, only escaping through the books of her father’s library. She’d expected to marry one of her father’s allies, then spend the rest of her life sequestered in his manor.

But expectations were like fine pottery. The harder you held them, the more likely they were to crack.

She found herself breathless, clutching her leather-bound drawing pad to her chest as longshoremen pulled the ship into the dock. Kharbranth was enormous. Built up the side of a steep incline, the city was wedge-shaped, as if it were built into a wide crack, with the open side toward the ocean. The buildings were blocky, with square windows, and appeared to have been constructed of some kind of mud or daub. Crem, perhaps? They were painted bright colors, reds and oranges most often, but occasional blues and yellows too.

She could hear the bells already, tinkling in the wind, ringing with pure voices. She had to strain her neck to look up toward the city’s loftiest rim; Kharbranth was like a mountain towering over her. How many people lived in a place like this? Thousands? Tens of thousands? She shivered again—daunted yet excited—then blinked pointedly, fixing the image of the city in her memory.

Sailors rushed about. The Wind’s Pleasure was a narrow, single-masted vessel, barely large enough for her, the captain, his wife, and the half-dozen crew. It had seemed so small at first, but Captain Tozbek was a calm and cautious man, an excellent sailor, even if he was a pagan. He’d guided the ship with care along the coast, always finding a sheltered cove to ride out highstorms.

The captain oversaw the work as the men secured the mooring. Tozbek was a short man, even-shouldered with Shallan, and he wore his long white Thaylen eyebrows up in a curious spiked pattern. It was like he had two waving fans above his eyes, a foot long each. He wore a simple knit cap and a silver-buttoned black coat. She’d imagined him getting that scar on his jaw in a furious sea battle with pirates. The day before, she’d been disappointed to hear it had been caused by loose tackle during rough weather.

His wife, Ashlv, was already walking down the gangplank to register their vessel. The captain saw Shallan inspecting him, and so walked over. He was a business connection of her family’s, long trusted by her father. That was good, since the plan she and her brothers had concocted had contained no place for her bringing along a lady-in-waiting or nurse.

That plan made Shallan nervous. Very, very nervous. She hated being duplicitous. But the financial state of her house … They either needed a spectacular infusion of wealth or some other edge in local Veden house politics. Otherwise, they wouldn’t last the year.

First things first, Shallan thought, forcing herself to be calm. Find Jasnah Kholin. Assuming she hasn’t moved off without you again.

“I’ve sent a lad on your behalf, Brightness,” Tozbek said. “If the princess is still here, we shall soon know.”

Shallan nodded gratefully, still clutching her drawing pad. Out in the city, there were people everywhere. Some wore familiar clothing—trousers and shirts that laced up the front for the men, skirts and colorful blouses for the women. Those could have been from her homeland, Jah Keved. But Kharbranth was a free city. A small, politically fragile city-state, it held little territory but had docks open to all ships that passed, and it asked no questions about nationality or status. People flowed to it.

That meant many of the people she saw were exotic. Those single-sheet wraps would mark a man or woman from Tashikk, far to the west. The long coats, enveloping down to the ankles, but open in the front like cloaks … where were those from? She’d rarely seen so many parshmen as she noted working the docks, carrying cargo on their backs. Like the parshmen her father had owned, these were stout and thick of limb, with their odd marbled skin—some parts pale or black, others a deep crimson. The mottled pattern was unique to each individual.

After chasing Jasnah Kholin from town to town for the better part of six months, Shallan was beginning to think she’d never catch the woman. Was the princess avoiding her? No, that didn’t seem likely—Shallan just wasn’t important enough to wait for. Brightness Jasnah Kholin was one of the most powerful women in the world. And one of the most infamous. She was the only member of a faithful royal house who was a professed heretic.

Shallan tried not to grow anxious. Most likely, they’d discover that Jasnah had moved on again. The Wind’s Pleasure would dock for the night, and Shallan would negotiate a price with the captain—steeply discounted, because of her family’s investments in Tozbek’s shipping business—to take her to the next port.

Already, they were months past the time when Tozbek had expected to be rid of her. She’d never sensed resentment from him; his honor and loyalty kept him agreeing to her requests. However, his patience wouldn’t last forever, and neither would her money. She’d already used over half the spheres she’d brought with her. He wouldn’t abandon her in an unfamiliar city, of course, but he might regretfully insist on taking her back to Vedenar.

“Captain!” a sailor said, rushing up the gangplank. He wore only a vest and loose, baggy trousers, and had the darkly tanned skin of one who worked in the sun. “No message, sir. Dock registrar says that Jasnah hasn’t left yet.”

“Ha!” the captain said, turning to Shallan. “The hunt is over!”

“Bless the Heralds,” Shallan said softly.

The captain smiled, flamboyant eyebrows looking like streaks of light coming from his eyes. “It must be your beautiful face that brought us this favorable wind! The windspren themselves were entranced by you, Brightness Shallan, and led us here!”

Shallan blushed, considering a response that wasn’t particularly proper.

“Ah!” the captain said, pointing at her. “I can see you have a reply—I see it in your eyes, young miss! Spit it out. Words aren’t meant to be kept inside, you see. They are free creatures, and if locked away will unsettle the stomach.”

“It’s not polite,” Shallan protested.

Tozbek bellowed a laugh. “Months of travel, and still you claim that! I keep telling you that we’re sailors! We forgot how to be polite the moment we set first foot on a ship; we’re far beyond redemption now.”

She smiled. She’d been trained by stern nurses and tutors to hold her tongue—unfortunately, her brothers had been even more determined in encouraging her to do the opposite. She’d made a habit of entertaining them with witty comments when nobody else was near. She thought fondly of hours spent by the crackling great-room hearth, the younger three of her four brothers huddled around her, listening as she made sport of their father’s newest sycophant or a traveling ardent. She’d often fabricated silly versions of conversations to fill the mouths of people they could see, but not hear.

That had established in her what her nurses had referred to as an “insolent streak.” And the sailors were even more appreciative of a witty comment than her brothers had been.

“Well,” Shallan said to the captain, blushing but still eager to speak, “I was just thinking this: You say that my beauty coaxed the winds to deliver us to Kharbranth with haste. But wouldn’t that imply that on other trips, my lack of beauty was to blame for us arriving late?”

“Well … er …”

“So in reality,” Shallan said, “you’re telling me I’m beautiful precisely one-sixth of the time.”

“Nonsense! Young miss, you’re like a morning sunrise, you are!”

“Like a sunrise? By that you mean entirely too crimson”—she pulled at her long red hair—”and prone to making men grouchy when they see me?”

He laughed, and several of the sailors nearby joined in. “All right then,” Captain Tozbek said, “you’re like a flower.”

She grimaced. “I’m allergic to flowers.”

He raised an eyebrow.

“No, really,” she admitted. “I think they’re quite captivating. But if you were to give me a bouquet, you’d soon find me in a fit so energetic that it would have you searching the walls for stray freckles I might have blown free with the force of my sneezes.”

“Well, be that true, I still say you’re as pretty as a flower.”

“If I am, then young men my age must be afflicted with the same allergy—for they keep their distance from me noticeably.” She winced. “Now, see, I told you this wasn’t polite. Young women should not act in such an irritable way.”

“Ah, young miss,” the captain said, tipping his knit cap toward her. “The lads and I will miss your clever tongue. I’m not sure what we’ll do without you.”

“Sail, likely,” she said. “And eat, and sing, and watch the waves. All the things you do now, only you shall have rather more time to accomplish all of it, as you won’t be stumbling across a youthful girl as she sits on your deck sketching and mumbling to herself. But you have my thanks, Captain, for a trip that was wonderful—if somewhat exaggerated in length.”

He tipped his cap to her in acknowledgment.

Shallan grinned—she hadn’t expected being out on her own to be so liberating. Her brothers had worried that she’d be frightened. They saw her as timid because she didn’t like to argue and remained quiet when large groups were talking. And perhaps she was timid—being away from Jah Keved was daunting. But it was also wonderful. She’d filled three sketchbooks with pictures of the creatures and people she’d seen, and while her worry over her house’s finances was a perpetual cloud, it was balanced by the sheer delight of experience.

Tozbek began making dock arrangements for his ship. He was a good man. As for his praise of her supposed beauty, she took that for what it was. A kind, if overstated, mark of affection. She was pale-skinned in an era when Alethi tan was seen as the mark of true beauty, and though she had light blue eyes, her impure family line was manifest in her auburn-red hair. Not a single lock of proper black. Her freckles had faded as she reached young womanhood—Heralds be blessed—but there were still some visible, dusting her cheeks and nose.

“Young miss,” the captain said to her after conferring with his men, “Your Brightness Jasnah, she’ll undoubtedly be at the Conclave, you see.”

“Oh, where the Palanaeum is?”

“Yes, yes. And the king lives there too. It’s the center of the city, so to speak. Except it’s on the top.” He scratched his chin. “Well, anyway, Brightness Jasnah Kholin is sister to a king; she will stay nowhere else, not in Kharbranth. Yalb here will show you the way. We can deliver your trunk later.”

“Many thanks, Captain,” she said. “Shaylor mkabat nour.” The winds have brought us safely. A phrase of thanks in the Thaylen language.

The captain smiled broadly. “Mkai bade fortenthis!”

She had no idea what that meant. Her Thaylen was quite good when she was reading, but hearing it spoken was something else entirely. She smiled at him, which seemed the proper response, for he laughed, gesturing to one of his sailors.

“We’ll wait here in this dock for two days,” he told her. “There is a highstorm coming tomorrow, you see, so we cannot leave. If the situation with the Brightness Jasnah does not proceed as hoped, we’ll take you back to Jah Keved.”

“Thank you again.”

“ ‘Tis nothing, young miss,” he said. “Nothing but what we’d be doing anyway. We can take on goods here and all. Besides, that’s a right nice likeness of my wife you gave me for my cabin. Right nice.”

He strode over to Yalb, giving him instructions. Shallan waited, putting her drawing pad back into her leather portfolio. Yalb. The name was difficult for her Veden tongue to pronounce. Why were the Thaylens so fond of mashing letters together, without proper vowels?

Yalb waved for her. She moved to follow.

“Be careful with yourself, lass,” the captain warned as she passed. “Even a safe city like Kharbranth hides dangers. Keep your wits about you.”

“I should think I’d prefer my wits inside my skull, Captain,” she replied, carefully stepping onto the gangplank. “If I keep them ‘about me’ instead, then someone has gotten entirely too close to my head with a cudgel.”

The captain laughed, waving her farewell as she made her way down the gangplank, holding the railing with her freehand. Like all Vorin women, she kept her left hand—her safehand—covered, exposing only her freehand. Common darkeyed women would wear a glove, but a woman of her rank was expected to show more modesty than that. In her case, she kept her safehand covered by the oversized cuff of her left sleeve, which was buttoned closed.

The dress was of a traditional Vorin cut, formfitting through the bust, shoulders, and waist, with a flowing skirt below. It was blue silk with chull-shell buttons up the sides, and she carried her satchel by pressing it to her chest with her safehand while holding the railing with her freehand.

She stepped off the gangplank into the furious activity of the docks, messengers running this way and that, women in red coats tracking cargos on ledgers. Kharbranth was a Vorin kingdom, like Alethkar and like Shallan’s own Jah Keved. They weren’t pagans here, and writing was a feminine art; men learned only glyphs, leaving letters and reading to their wives and sisters.

She hadn’t asked, but she was certain Captain Tozbek could read. She’d seen him holding books; it had made her uncomfortable. Reading was an unseemly trait in a man. At least, men who weren’t ardents.

“You wanna ride?” Yalb asked her, his rural Thaylen dialect so thick she could barely make out the words.

“Yes, please.”

He nodded and rushed off, leaving her on the docks, surrounded by a group of parshmen who were laboriously moving wooden crates from one pier to another. Parshmen were thick-witted, but they made excellent workers. Never complaining, always doing as they were told. Her father had preferred them to ordinary slaves.

Were the Alethi really fighting parshmen out on the Shattered Plains? That seemed so odd to Shallan. Parshmen didn’t fight. They were docile and practically mute. Of course, from what she’d heard, the ones out on the Shattered Plains—the Parshendi, they were called—were physically different from normal parshmen. Stronger, taller, keener of mind. Perhaps they weren’t really parshmen at all, but distant relatives of some kind.

To her surprise, she could see signs of animal life all around the docks. A few skyeels undulated through the air, searching for rats or fish. Tiny crabs hid between cracks in the dock’s boards, and a cluster of haspers clung to the dock’s thick logs. In a street inland of the docks, a prowling mink skulked in the shadows, watching for morsels that might be dropped.

She couldn’t resist pulling open her portfolio and beginning a sketch of a pouncing skyeel. Wasn’t it afraid of all the people? She held her sketchpad with her safehand, hidden fingers wrapping around the top as she used a charcoal pencil to draw. Before she was finished, her guide returned with a man pulling a curious contraption with two large wheels and a canopy-covered seat. She hesitantly lowered her sketchpad. She’d expected a palanquin.

The man pulling the machine was short and dark-skinned, with a wide smile and full lips. He gestured for Shallan to sit, and she did so with the modest grace her nurses had drilled into her. The driver asked her a question in a clipped, terse-sounding language she didn’t recognize.

“What was that?” she asked Yalb.

“He wants to know if you’d like to be pulled the long way or the short way.” Yalb scratched his head. “I’m not right sure what the difference is.”

“I suspect one takes longer,” Shallan said.

“Oh, you are a clever one.” Yalb said something to the porter in that same clipped language, and the man responded.

“The long way gives a good view of the city,” Yalb said. “The short way goes straight up to the Conclave. Not many good views, he says. I guess he noticed you were new to the city.”

“Do I stand out that much?” Shallan asked, flushing.

“Eh, no, of course not, Brightness.”

“And by that you mean that I’m as obvious as a wart on a queen’s nose.”

Yalb laughed. “Afraid so. But you can’t go someplace a second time until you been there a first time, I reckon. Everyone has to stand out sometime, so you might as well do it in a pretty way like yourself!”

She’d had to get used to gentle flirtation from the sailors. They were never too forward, and she suspected the captain’s wife had spoken to them sternly when she’d noticed how it made Shallan blush. Back at her father’s manor, servants—even those who had been full citizens—had been afraid to step out of their places.

The porter was still waiting for an answer. “The short way, please,” she told Yalb, though she longed to take the scenic path. She was finally in a real city and she took the direct route? But Brightness Jasnah had proven to be as elusive as a wild songling. Best to be quick.

The main roadway cut up the hillside in switchbacks, and so even the short way gave her time to see much of the city. It proved intoxicatingly rich with strange people, sights, and ringing bells. Shallan sat back and took it all in. Buildings were grouped by color, and that color seemed to indicate purpose. Shops selling the same items would be painted the same shades—violet for clothing, green for foods. Homes had their own pattern, though Shallan couldn’t interpret it. The colors were soft, with a washed-out, subdued tonality.

Yalb walked alongside her cart, and the porter began to talk back toward her. Yalb translated, hands in the pockets of his vest. “He says that the city is special because of the lait here.”

Shallan nodded. Many cities were built in laits—areas protected from the highstorms by nearby rock formations.

“Kharbranth is one of the most sheltered major cities in the world,” Yalb continued, translating, “and the bells are a symbol of that. It’s said they were first erected to warn that a highstorm was blowing, since the winds were so soft that people didn’t always notice.” Yalb hesitated. “He’s just saying things because he wants a big tip, Brightness. I’ve heard that story, but I think it’s blustering ridiculous. If the winds blew strong enough to move bells, then people’d notice. Besides, people didn’t notice it was raining on their blustering heads?”

Shallan smiled. “It’s all right. He can continue.”

The porter chatted on in his clipped voice—what language was that, anyway? Shallan listened to Yalb’s translation, drinking in the sights, sounds, and—unfortunately—scents. She’d grown up accustomed to the crisp smell of freshly dusted furniture and flatbread baking in the kitchens. Her ocean journey had taught her new scents, of brine and clean sea air.

There was nothing clean in what she smelled here. Each passing alleyway had its own unique array of revolting stenches. These alternated with the spicy scents of street vendors and their foods, and the juxtaposition was even more nauseating. Fortunately, her porter moved into the central part of the roadway, and the stenches abated, though it did slow them as they had to contend with thicker traffic. She gawked at those they passed. Those men with gloved hands and faintly bluish skin were from Natanatan. But who were those tall, stately people dressed in robes of black? And the men with their beards bound in cords, making them rodlike?

The sounds put Shallan in mind of the competing choruses of wild songlings near her home, only multiplied in variety and volume. A hundred voices called to one another, mingling with doors slamming, wheels rolling on stone, occasional skyeels crying. The ever-present bells tinkled in the background, louder when the wind blew. They were displayed in the windows of shops, hung from rafters. Each lantern pole along the street had a bell hung under the lamp, and her cart had a small silvery one at the very tip of its canopy. When she was about halfway up the hillside, a rolling wave of loud clock bells rang the hour. The varied, unsynchronized chimes made a clangorous din.