Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from Lamentation by Ken Scholes, beginning an epic series about a clash of nations on a distant future Earth. The saga of the Named Lands concludes in Hymn, available December 5th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from Lamentation by Ken Scholes, beginning an epic series about a clash of nations on a distant future Earth. The saga of the Named Lands concludes in Hymn, available December 5th.

This remarkable first novel from award-winning short fiction writer Ken Scholes will take readers away to a new world—an Earth so far in the distant future that our time is not even a memory; a world where magick is commonplace and great areas of the planet are impassable wastes. But human nature hasn’t changed through the ages: War and faith and love still move princes and nations.

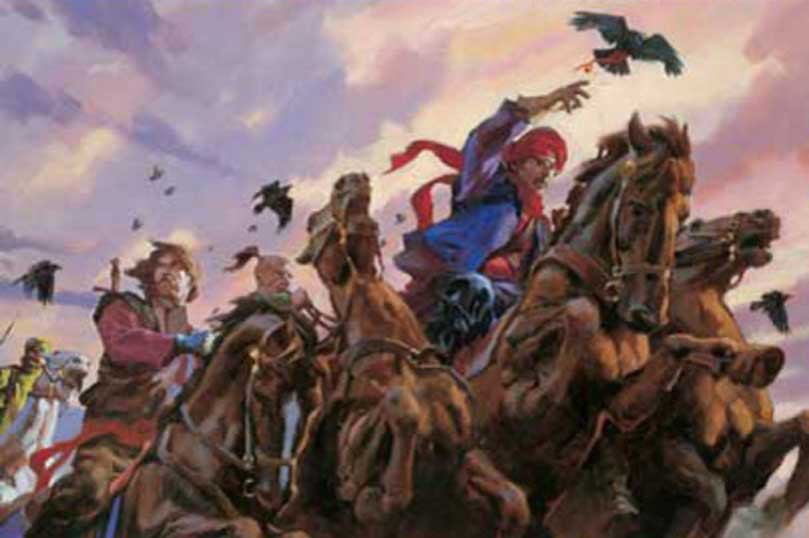

An ancient weapon has completely destroyed the city of Windwir. From many miles away, Rudolfo, Lord of the Nine Forest Houses, sees the horrifying column of smoke rising. He knows that war is coming to the Named Lands.

Nearer to the Devastation, a young apprentice is the only survivor of the city—he sat waiting for his father outside the walls, and was transformed as he watched everyone he knew die in an instant.

Soon all the Kingdoms of the Named Lands will be at each others’ throats, as alliances are challenged and hidden plots are uncovered.

Prelude

Windwir is a city of paper and robes and stone.

It crouches near a wide and slow-moving river at the edge of the Named Lands. Named for a poet turned Pope—the first Pope in the New World. A village in the forest that became the center of the world. Home of the Androfrancine Order and their Great Library. Home of many wonders both scientific and magickal.

One such wonder watches from high above.

It is a bird made of metal, a gold spark against the blue expanse that catches the afternoon sun. The bird circles and waits.

When the song begins below, the golden bird watches the melody unfold. A shadow falls across the city and the air becomes still. Tiny figures stop moving and look up. A flock of birds lifts and scatters. The sky is torn and fire rains down until only utter darkness remains. Darkness and heat.

The heat catches the bird and tosses it farther into the sky. A gear slips; the bird’s wings compensate, but a billowing, black cloud takes an eye as it passes.

The city screams and then sighs seven times, and after the seventh sigh, sunlight returns briefly to the scorched land. The plain is blackened, the spires and walls and towers all brought down into craters where basements collapsed beneath the footprint of Desolation. A forest of bones, left whole by ancient blood magick, stands on the smoking, pockmarked plain.

Darkness swallows the light again as a pillar of smoke and ash blots out the sun. Finally, the golden bird flees southwest.

It easily overtakes the other birds, their wings smoking and beating furiously against the hot winds, messages tied to their feet with threads of white or red or black.

Sparking and popping, the golden bird speeds low across the landscape and dreams of its waiting cage.

Chapter 1

Rudolfo

Wind swept the Prairie Sea and Rudolfo chased after it, laughing and riding low in the saddle as he raced his Gypsy Scouts. The afternoon sun glinted gold on the bending grass and the horses pounded out their song.

Rudolfo savored the wide yellow ocean of grass that separated the Ninefold Forest Houses from one another and from the rest of the Named Lands—it was his freedom in the midst of duty, much as the oceans must have been for the seagoing lords of the Elder Days. He smiled and spurred his stallion.

It had been a fine time in Glimmerglam, his first Forest House. Rudolfo had arrived before dawn. He’d taken his breakfast of goat cheese, whole grain bread and chilled pear wine beneath a purple canopy that signified justice. While he ate, he heard petitions quietly as Glimmerglam’s steward brought the month’s criminals forward. Because he felt particularly benevolent, he sent two thieves into a year’s servitude to the shopkeepers they’d defiled, while sending the single murderer to his Physicians of Penitent Torture on Tormentor’s Row. He dismissed three cases of prostitution and then afterward, hired two of them onto his monthly rotation.

By lunchtime, Rudolfo had proven Aetero’s Theory of Compensatory Seduction decidedly false and he celebrated with creamed pheasant served over brown rice and wild mushrooms.

Then with his belly full, he’d ridden out with a shout, his Gypsy Scouts racing to keep up with him.

A good day indeed.

“What now,” the Captain of his Gypsy Scouts asked him, shouting above the pounding hooves.

Rudolfo grinned. “What say you, Gregoric?”

Gregoric returned the smile and it made his scar all the more ruthless. His black scarf of rank trailed out behind him, ribboning on the wind. “We’ve seen to Glimmerglam, Rudoheim and Friendslip. I think Paramo is the closest.”

“Then Paramo it is.” That would be fitting, Rudolfo thought. It couldn’t come close to Glimmerglam’s delights, but it had held on to its quaint, logging village atmosphere for at least a thousand years and that was an accomplishment. They floated their timber down the Rajblood River just as they had in the first days, retaining what they needed to build some of the world’s most intricately crafted woodwork. The lumber for Rudolfo’s manors came from the trees of Paramo. The furniture they made rolled out by the wagonload and the very best found its way into the homes of kings and priests and nobility from all over the Named Lands.

He would dine on roast boar tonight, listen to the boasting and flatulence of his best men, and sleep on the ground with a saddle beneath his head—the life of a Gypsy King. And tomorrow, he’d sip chilled wine from the navel of a log camp dancer, listen to the frogs in the river shallows mingled with her sighs, and then sleep in the softest of beds on the summer balcony of his third forest manor.

Rudolfo smiled.

But as he rounded to the south, his smile faded. He reined in and squinted against the sunlight. The Gypsy Scouts followed his lead, whistling to their horses as they slowed, stopped and then pranced.

“Gods,” Gregoric said. “What could cause such a thing?”

Southwest of them, billowing up above the horizon of forest-line that marked Rudolfo’s farthest border, a distant pillar of black smoke rose like a fist in the sky.

Rudolfo stared and his stomach lurched. The size of the smoke cloud daunted him; it was impossible. He blinked as his mind unlocked enough for him to do the math, quickly calculating the distance and direction based on the sun and the few stars strong enough to shine by day.

“Windwir,” he said, not even aware that he was speaking.

Gregoric nodded. “Aye, General. But what could do such a thing?”

Rudolfo looked away from the cloud to study his captain. He’d known Gregoric since they were boys, and had made him the youngest captain of the Gypsy Scouts at fifteen when Rudolfo himself was just twelve. They’d seen a lot together, but Rudolfo had never seen him pale before now.

“We’ll know soon enough,” Rudolfo said. Then he whistled his men in closer. “I want riders back to each of the houses to gather the Wandering Army. We have kin-clave with Windwir; their birds will be flying. We’ll meet on the Western Steppes in one day; we’ll be to Windwir’s aid in three.”

“Are we to magick the scouts, General?”

Rudolfo stroked his beard. “I think not.” He thought for a moment. “But we should be ready,” he added.

Gregoric nodded and barked out the orders.

As the nine Gypsy Scouts rode off, Rudolfo slipped from the saddle, watching the dark pillar. The column of smoke, as wide as a city, disappeared into the sky.

Rudolfo, Lord of the Ninefold Forest Houses, General of the Wandering Army, felt curiosity and fear dance a shiver along his spine.

“What if it’s not there when we arrive?” he asked himself.

And he knew—but did not want to—that it wouldn’t be, and that because of this, the world had changed.

Petronus

Petronus mended the last of the net and tucked it away in the prow of his boat. Another quiet day on the water, another day of little to show for it, but he was happy with that.

Tonight, he’d dine at the inn with the others, eating and drinking too much and finally breaking down into the raunchy limericks that made him famous up and down the coast of Caldus Bay. Petronus didn’t mind being famous for that at all. Outside of his small village, most had no idea that more fame than that lay just beneath the surface.

Petronus the Fisherman had lived another life before returning to his nets and his boat. Prior to the day he chose to end that life, Petronus had lived a lie that, at times, felt more true than a child’s love. Nonetheless, it was a lie that ate away at him until he stood up to it and laid it out thirty-three years ago.

Next week, he realized with a smile. He could go months without thinking about it now. When he was younger, it wasn’t so. But each year, about a month before the anniversary of his rather sudden and creative departure, memories of Windwir, of its Great Library, of its robed Order, flooded him and he found himself tangled up in his past like a gull in a net.

The sun danced on the water, and he watched the silver waves flash against the hulls of ships both small and large. Overhead, a clear blue sky stretched as far as he could see and seabirds darted, shrieking their hunger as they dove for the small fish that dared swim near the surface.

One particular bird—a kingfisher—caught his eye and he followed it as it dipped and weaved. He turned with it, watching as it flexed its wings and glided, pushed back by a high wind that Petronus couldn’t see or feel.

I’ve been pushed by such a wind, he thought, and with that thought, the bird suddenly shuddered in the air as the wind overcame it and pushed it farther back.

Then Petronus saw the cloud piling up on the horizon to the northwest.

He needed no mathematics to calculate the distance. He needed no time at all to know exactly what it was and what it meant.

Windwir.

Stunned, he slid to his knees, his eyes never leaving the tower of smoke that rose westward and north of Caldus Bay. It was close enough that he could see the flecks of fire in it as it roiled and twisted its way into the sky.

“ ‘Oh my children,’ ” Petronus whispered, quoting the First Gospel of P’Andro Whym, “‘what have you done to earn the wrath of heaven?’”

Jin Li Tam

Jin Li Tam bit back her laughter and let the fat Overseer try to reason with her.

“It’s not seemly,” Sethbert said, “for the consort of a king to ride sidesaddle.”

She did not bother to remind him of the subtle differences between an Overseer and a king. Instead, she stayed with her point. “I do not intend to ride sidesaddle, either, my lord.”

Jin Li Tam had spent most of the day cramped into the back of a carriage with the Overseer’s entourage and she’d had enough of it. There was an army of horses to be had—saddles, too—and she meant to feel the wind on her face. Besides, she could see little from the inside of a carriage and she knew her father would want a full report.

A captain interrupted, pulling Sethbert aside and whispering urgently. Jin Li Tam took it as her cue to slip away in search of just the right horse—and to get a better idea of what was afoot.

She’d seen the signs for over a week. Messenger birds coming and going, cloaked couriers galloping to and fro at all hours of the night. Long meetings between old men in uniforms, hushed voices and then loud voices, and hushed voices again. And the army had come together quickly, brigades from each of the City States united under a common flag. Now, they stretched ahead and behind on the Whymer Highway, overflowing the narrow road to trample the fields and forests in their forced march north.

Try as she might, she had no idea why. But she knew the scouts were magicked, and according to the Rites of Kin-Clave, that meant Sethbert and the Entrolusian City States were marching to war. And she also knew that very little lay north apart from Windwir—the great seat of the Androfrancine Order—and farther north and east, Rudolfo’s Ninefold Forest Houses. But both of those neighbors were Kin-Clave with the Entrolusians, and she’d not heard of any trouble they might be in that merited Entrolusian intervention.

Of course, Sethbert had not been altogether rational of late.

Though she cringed at the thought of it, she’d shared his bed enough to know that he was talking in his sleep and restless, unable to rise to the challenge of his young redheaded consort. He was also smoking more of the dried kallaberries, intermittently raging and rambling with his officers. Yet they followed him, so there had to be something. He didn’t possess the charm or charisma to move an army on his own and he was too lazy to move them by ruthlessness, while lacking in the more favorable motivational skills.

“What are you up to?” she wondered out loud.

“Milady?” A young cavalry lieutenant towered over her on a white mare. He had another horse in tow behind him.

She smiled, careful to turn in such a way that he could see down her top just far enough to be rewarded, but not so far as to be improper. “Yes, Lieutenant?”

“Overseer Sethbert sends his compliments and requests that you join him forward.” The young man pulled the horse around, offering her the reins.

She accepted and nodded. “I trust you will ride with me?”

He nodded. “He asked me to do so.”

Climbing into the saddle, she adjusted her riding skirts and stretched up in the stirrups. Twisting, she could make out the end of the long line of soldiers behind and before her. She nudged the horse forward. “Then let’s not keep the Overseer waiting.”

Sethbert waited at a place where the highway crested a rise. She saw the servants setting up his scarlet canopy at the road’s highest point and wondered why they were stopping here, in the middle of nowhere.

He waved to her as she rode up. He looked flushed, even excited. His jowls shook and sweat beaded on his forehead. “It’s nearly time,” he said. “Nearly time.”

Jin looked at the sky. The sun was at least four hours from setting. She looked back at him, then slid from the saddle. “Nearly time for what, my lord?”

They were setting up chairs now for them, pouring wine, preparing platters. “Oh you’ll see,” Sethbert said, placing his fat behind into a chair that groaned beneath him.

Jin Li Tam sat, accepted wine and sipped.

“This,” Sethbert said, “is my finest hour.” He looked over to her and winked. His eyes had that glazed over, faraway look they sometimes had during their more intimate moments. A look she wished she could afford the luxury of having during those moments as well and still be her father’s spy.

“What—” But she stopped herself. Far off, beyond the forests and past the glint of the Third River as it wound its way northward, light flashed in the sky and a small crest of smoke began to lift itself on the horizon. The small crest expanded upward and outward, a column of black against the blue sky that kept growing and growing.

Sethbert chuckled and reached over to squeeze her knee. “Oh. It’s better than I thought.” She forced her eyes away for long enough to see his wide smile. “Look at that.”

And now, there were gasps and whispers that grew to a buzz around them. There were arms lifted, fingers pointing north. Jin Li Tam looked away again to take in the pale faces of Sethbert’s generals and captains and lieutenants, and she knew that if she could see all the way back to the line upon line of soldiers and scouts behind her, she’d see the same fear and awe upon their faces, too. Perhaps, she thought, turning her eyes back onto that awful cloud as it lifted higher and higher into the sky, that fear and awe painted every face that could see it for miles and miles around. Perhaps everyone knew what it meant.

“Behold,” Sethbert said in a quiet voice, “the end of the Androfrancine tyranny. Windwir is fallen.” He chuckled. “Tell that to your father.”

And when his chuckle turned into a laugh, Jin Li Tam heard the madness in him for the first time.

Neb

Neb stood in the wagon and watched Windwir stretch out before him. It had taken them five hours to climb the low hills that hemmed the great city in, and now that he could see it he wanted to take it all in, to somehow imprint it on his brain. He was leaving that city for the first time and it would be months before he saw it again.

His father, Brother Hebda, stood as well, stretching in the morning sun. “And you have the bishop’s letters of introduction and credit?” Brother Hebda asked.

Neb wasn’t paying attention. Instead, the massive city filled his view—the cathedrals, the towers, the shops and houses pressed in close against the walls. The colors of kin-clave flew over her, mingled with the royal blue colors of the Androfrancine Order, and even from this vantage, he could see the robed figures bustling about.

His father spoke again and Neb started. “Brother Hebda?”

“I asked after the letters of introduction and credit. You were reading them this morning before we left and I told you to make sure you put them back in their pouch.”

Neb tried to remember. He remembered seeing them on his father’s desk and asking if he could look at them. He remembered reading them, being fascinated with the font and script of them. But he couldn’t remember putting them back. “I think I did,” he said.

They climbed into the back of the wagon and went through each pouch, pack and sack. When they didn’t find them, his father sighed.

“I’ll have to go back for them,” he said.

Neb looked away. “I’ll come with you, Brother Hebda.”

His father shook his head. “No. Wait here for me.”

Neb felt his face burn hot, felt a lump in his throat. The bulky scholar reached out and squeezed Neb’s shoulder. “Don’t fret over it. I should’ve checked it myself.” He squinted, looking for the right words. “I’m just . . . not used to having anyone else about.”

Neb nodded. “Can I do anything while you’re gone?”

Brother Hebda had smiled. “Read. Meditate. Watch the cart. I’ll be back soon.”

![]()

Neb drew Whymer Mazes in the dirt and tried to concentrate on his meditation. But everything called him away. First the sounds of the birds, the wind, the champing of the horse. And the smell of evergreen and dust and horse-sweat. And his sweat, too, now dried after five long hours in the shade.

He’d waited for years. Every year he’d petitioned the headmaster for a grant, and now, just one year shy of manhood and the ability to captain his own destiny without the approval of the Franci Orphanage, he’d finally been released to study with his father. The Androfrancines could not prove their vow of chastity if they had children on their arms, so the Franci Orphanage looked after them all. None knew their birth-mothers and only a few knew their fathers.

Neb’s father had actually come to see him at least twice a year and had sent him gifts and books from far off places while he dug in Churning Wastes, studying times before the Age of Laughing Madness. And one time, years ago, he’d even told Neb that someday he’d bring the boy along so that he could see what the love of P’Andro Whym was truly about, a love so strong that it would cause a man to sacrifice his only begotten son.

Finally, Neb received his grant.

And here at the beginning of his trip to the Wastes, he’d already disappointed the man he most wanted to make proud.

![]()

Five hours had passed, and even though there was no way to pick him out from such a distance, Neb stood every so often and looked down toward the city, watching the gate near the river docks.

He’d just sat down from checking yet again when the hair on his arms stood up and the world went completely silent but for a solitary, tinny voice far away. He leaped to his feet. Then, a heavy buzzing grew in his ears and his skin tingled from a sudden wind that seemed to bend the sky. The buzzing grew to a shriek and his eyes went wide as they filled with both light and darkness, and he stood transfixed, arms stretched wide, standing at his full height, mouth hanging open.

The ground shook and he watched the city wobble as the shrieking grew. Birds scattered out from the city, specks of brown and white and black that he could barely see in the ash and debris that the sudden, hot wind stirred.

Spires tumbled and rooftops collapsed. The walls trembled and gave up, breaking apart as they fell inward. Fires sprang up—a rainbow kaleidoscope of colors—licking at first and then devouring. Neb watched the tiny robed forms of bustling life burst into flame. He watched lumbering dark shadows move through the roiling ash, laying waste to anything that dared to stand. He watched flaming sailors leap from burning bows as the ships cast off and begged the current save them. But ships and sailors alike kept burning, green and white, as they sank beneath the waters. There was the sound of cracking stone and boiling water, the smell of heated rock and charred meat. And the pain of the Desolation of Windwir racked his own body. Neb shrieked when he felt this heart burst or that body bloat and explode.

The world roared at him, fire and lightning leaping up and down the sky as the city of Windwir screamed and burned. All the while, an invisible force held Neb in place and he screamed with his city, eyes wide open, mouth wide open, lungs pumping furiously against the burning air.

A single bird flew out from the dark cloud, hurtling past Neb’s head and into the forest behind him. For the briefest moment he thought it was made of gold.

Hours later, when nothing was left but the raging fire, Neb fell to his knees and sobbed into the dirt. The tower of ash and smoke blotted out the sun. The smell of death choked his nostrils. He sobbed there until he had no more tears and then he lay shaking and twitching, his eyes opening and closing on the desolation below.

Finally, Neb sat up and closed his eyes. Mouthing the Gospel Precepts of P’Andro Whym, Founder of the Androfrancines, he meditated upon the folly in his heart.

The folly that had caused his father’s death.

Chapter 2

Jin Li Tam

Jin Li Tam watched the grass and ferns bend as Sethbert’s magicked scouts slipped to and from their hidden camp. Because her father had trained her well, she could just make out the outline of them when they passed beneath the rays of sunlight that pierced the canopy of forest. But in shadows, they were ghosts—silent and transparent. She waited to the side of the trail just outside of camp, watching.

Sethbert had pulled them up short, several leagues outside of Windwir. He’d ridden ahead with his scouts and generals, twitching and short-tempered upon leaving but grinning and chortling upon his return. Jin Li Tam noted that he was the only one who looked pleased. The others looked pale, shaken, perhaps even mortified. Then she caught a bit of their conversation.

“I’d have never agreed to this if I’d known it could do that,” one of the generals was saying.

Sethbert shrugged. “You knew it was a possibility. You’ve sucked the same tit the rest of us have—P’Andro Whym and Xhum Y’Zir and the Age of the Laughing Madness and all that other sour Androfrancine milk. You know the stories, Wardyn. It was always a possibility.”

“The library is gone, Sethbert.”

“Not necessarily,” another voice piped up. This was the Androfrancine that had met them on the road the day before—an apprentice to someone who worked in the library. Of course, Jin Li Tam had also seen him around the palace; he had brought Sethbert the metal man last year and had visited from time to time in order to teach it new tricks. He continued speaking. “The mechoservitors have long memories. Once we’ve gathered them up, they could help restore some of the library.”

“Possibly,” Sethbert said in an uninterested voice. “Though I think ultimately they may have more strategic purposes.”

The general gasped. “You can’t mean—”

Sethbert raised a hand as he caught sight of Jin Li Tam to the side of the trail. “Ah, my lovely consort awaiting my return, all aflutter, no doubt.”

She slipped from the shadows and curtsied. “My lord.”

“You should’ve seen it, love,” Sethbert said, his eyes wide like a child’s. “It was simply stunning.”

She felt her stomach lurch. “I’m sure it was a sight to behold.”

Sethbert smiled. “It was everything I hoped for. And more.” He looked around, as if suddenly remembering his men. “We’ll talk later,” he told them. He watched them ride on, then turned back to Jin. “We’re expecting a state banquet tomorrow,” he told her in a low voice. “I’m told Rudolfo and his Wandering Army will be arriving sometime before noon.” His eyes narrowed. “I will expect you to shine for me.”

She’d not met the Gypsy King before, though her father had and had spoken of him as formidable and ruthless, if slightly foppish. The Ninefold Forest Houses kept largely to themselves, far out on the edge of the New World away from the sleeping cities of the Three Rivers Delta and the Emerald Coasts.

Jin Li Tam bowed. “Don’t I always shine for you, my lord?”

Sethbert laughed. “I think you only shine for your father, Jin Li Tam. I think I’m just a whore’s tired work.” He leaned in and grinned. “But Windwir changes that, doesn’t it?”

Sethbert calling her a whore did not surprise her, and it did not bristle her, either. Sethbert truly was her tired work. But the fact that he’d openly spoken of her father twice now in so many days gave Jin pause. She wondered how long he’d known. Not too long, she hoped.

Jin swallowed. “What do you mean?”

His face went dark. “We both know that your father has also played the whore, dancing for coins in the lap of the Androfrancines, whispering tidbits of street gossip into their hairy ears. His time is past. You and your brothers and sisters will soon be orphans. You should start to think about what might be best for you before you run out of choices.” Then the light returned to him and his voice became almost cheerful. “Dine with me tonight,” he said, before standing up on his tiptoes to kiss her cheek. “We’ll celebrate the beginning of new things.”

Jin shuddered and hoped he didn’t notice.

She was still standing in the same place, shaking with rage and fear, long after Sethbert had returned whistling to camp.

Petronus

Petronus couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t fish or eat, either. For two days, he sat on his porch and watched the smoke of Windwir gradually dissipate to the northwest. Few birds came to Caldus Bay, but ships passed through daily on their way to the Emerald Coasts. Still, he knew it was too early for any word. And he knew from the smoke that there could be no good news, regardless.

Hyram, the old Mayor and Petronus’s closest friend from boyhood, stopped by each afternoon to check on him. “Still no word,” he told Petronus on the third afternoon. “A few City Staters said Sethbert marched north with his army to honor Entrolusia’s kin-clave. Though some are saying he started riding a full day before the cloud appeared. And the Gypsy King rallied his Wandering Army on the Western Steppes. Their quartermasters were in town buying up foodstuffs.”

Petronus nodded, eyes never leaving the sky. “They’re the closest of Windwir’s kin-clave. They’re probably there now.”

“Aye.” Hyram shifted uncomfortably on the bench. “So what will you do?”

“Do?” Petronus blinked. “I won’t do anything. It’s not my place.”

Hyram snorted. “It’s more your place than anyone else’s.”

Petronus looked away from the sky now, his eyes narrowing as he took in his friend. “Not anymore,” he said. “I left that life.” He swallowed. “Besides, we don’t know how bad things are.”

“Two days of smoke,” Hyram said. “We know how bad things are. And how many Androfrancines would be outside the city during the Week of Knowledgeable Conference?”

Petronus thought for a moment. “A thousand, maybe two.”

“Out of a hundred thousand?” Hyram asked.

Petronus nodded. “And that’s just the Order. Windwir was twice that easily.” Then he repeated himself. “But we don’t know how bad things are.”

“You could send a bird,” Hyram offered.

Petronus shook his head. “It’s not my place. I left the Order behind. You of all people know why.”

Hyram and Petronus had both left for Windwir together when they were young men. Tired of the smell of fish on their hands, eager for knowledge and adventure, they’d both become acolytes. A few years later, Hyram had returned home for a simpler life while Petronus had gone on to climb the ecclesiastical ranks and make his mark upon that world.

Hyram nodded. “I do know why. I don’t know how you stomached it for as long as you did. But you loved it at one point.”

“I still love it,” Petronus said. “I just love what it was . . . love how it started and what it stood for. Not what it became. P’Andro Whym would weep to see what we’ve done with it. He never meant for us to grow rich upon the spoils of knowledge, for us to make or break kings with a word.” Petronus’s words became heavy with feeling as he quoted a man whose every written word he had at one point memorized: “Behold, I set you as a tower of reason against this Age of Laughing Madness, and knowledge shall be thy light and the darkness shall flee from it.”

Hyram was quiet for a minute. Then he repeated his question. “So what will you do?”

Petronus rubbed his face. “If they ask me, I will help. But I won’t give them the help they want. I’ll give them the help they need.”

“And until then?”

“I’ll try to sleep. I’ll go back to fishing.”

Hyram nodded and stood. “So you’re not curious at all?”

But Petronus didn’t answer. He was back to watching the northwestern sky and didn’t even notice when his friend quietly slipped away.

Eventually, when the light gave out, he went inside and tried to take some soup. His stomach resisted it, and he lay in bed for hours while images of his past rode parade before his closed eyes. He remembered the heaviness of the ring on his finger, the crown on his brow, the purple robes and royal blue scarves. He remembered the books and the magicks and the machines. He remembered the statues and the tombs, the cathedrals and the catacombs.

He remembered a life that seemed simpler now because in those days he’d loved the answers more than the questions.

After another night of tossing and sweating in his sheets, Petronus rose before the earliest fishermen, packed lightly, and slipped into the crisp morning. He left a note for Hyram on the door, saying he would be back when he’d seen it for himself.

By the time the sun rose, he was six leagues closer to knowing what had happened to the city and way of life that had once been his first love, his most beautiful, backward dream.

Neb

Neb couldn’t remember most of the last two days. He knew he’d spent it meditating and poring over his tattered copy of the Whymer Bible and its companion, the Compendium of Historic Remembrance. His father had given them to him.

Of course, he knew there were other books in the cart. There was also food there and clothing and new tools wrapped in oilcloth. But he couldn’t bring himself to touch it. He couldn’t bring himself to move much at all.

So instead, he sat in the dry heat of the day and the crisp chill of the night, rocking himself and muttering the words of his reflection, the lines of his gospel, the quatrains of his lament.

Movement in the river valley below brought him out of it. Men on horseback rode to the blackened edge of the smoldering city, disappearing into smoke that twisted and hung like souls of the damned. Neb lay flat on his stomach and crept to the edge of the ridge. A bird whistled, low and behind him.

No, he thought, not a bird. He pushed himself up to all fours and slowly turned.

There was no wind. Yet he felt it brushing him as ghosts slipped in from the forest to surround him.

Standing quickly, Neb staggered into a run.

An invisible arm grabbed him and held him fast. “Hold, boy.” The whispered voice sounded like it was spoken into a room lined with cotton bales.

There, up close, he could see the dark silk sleeve, the braided beard and broad shoulder of a man. He struggled and more arms appeared, holding him and forcing him to the ground.

“We’ll not harm you,” the voice said again. “We’re Scouts of the Delta.” The scout paused to let the words take root. “Are you from Windwir?”

Neb nodded.

“If I let you go, will you stay put? It’s been a long day in the woods and I’m not wanting to chase you.”

Neb nodded again.

The scout released him and backed away. Neb sat up slowly and studied the clearing around him. Crouched around him, barely shimmering in the late morning light, were at least a half dozen men.

“Do you have a name?”

He opened his mouth to speak, but the only words that came out were a rush of scripture, bits of the Gospels of P’Andro Whym all jumbled together into run-on sentences that were nonsensical. He closed his mouth and shook his head.

“Bring me a bird,” the scout captain said. A small bird appeared, cupped in transparent hands. The scout captain pulled a thread from his scarf and tied a knot-message into it, looping it around the bird’s foot. He hefted the bird into the sky.

They sat in silence for an hour, waiting for the bird to return. Once it was folded safely back into its pouch cage, the scout captain pulled Neb to his feet. “I am to inform you that you are to be the guest of Lord Sethbert, Overseer of the Entrolusian City States and the Delta of the Three Rivers. He is having quarters erected for you in his camp. He eagerly awaits your arrival and wishes to know in great detail all you know of the Fall of Windwir.”

When they nudged him toward the forest, he resisted and turned toward the cart.

“We’ll send men back for it,” the scout captain said. “The Overseer is anxious to meet you.”

Neb wanted to open his mouth and protest, but he didn’t. Something told him that even if he could, these men were not going to let him come between them and their orders.

Instead, he followed them in silence. They followed no trails, left no trace and made very little sound, yet he knew they were all around him. And whenever he strayed, they nudged him back on course. They walked for two hours before breaking into a concealed camp. A short, obese man in bright colors stood next to a tall, redheaded woman with a strange look on her face.

The obese man smiled broadly, stretching out his arms, and Neb thought that he seemed like that kindly father in the Tale of the Runaway Prince, running toward his long lost son with open arms.

But the look on the woman’s face told Neb that it was not so.

Rudolfo

Rudolfo let his Wandering Army choose their campsite because he knew they would fight harder to keep what they had chosen themselves. They set up their tents and kitchens upwind of the smoldering ruins in the low hills just west, while Rudolfo’s Gypsy Scouts searched the outlying areas cool enough for them to walk. So far, they’d found no survivors.

Rudolfo ventured close enough to see the charred bones and smell the marrow cooking on the hot wind. From there, he directed his men.

“Search in shifts as it cools,” Rudolfo said. “Send a bird if you find anything.”

Gregoric nodded. “I will, General.”

Rudolfo shook his head. When he’d first crested the rise and seen the Desolation of Windwir, he ripped his scarf and cried loudly so his men could see his grief. Now, he cried openly and so did Gregoric. The tears cut through the grime on his face. “I don’t think you’ll find anyone,” Rudolfo said.

“I know, General.”

While they searched, Rudolfo reclined in his silk tent and sipped plum wine and nibbled at fresh cantaloupe and sharp cheddar cheese. Memories of the world’s greatest city flashed across his mind, juxtaposing themselves against images of it now, burning outside. “Gods,” he whispered.

His first memory was the Pope’s funeral. The one who had been poisoned. Rudolfo’s father, Jakob, had brought him to the City for the Funereal Honors of Kin-Clave. Rudolfo had even ridden with his father, hanging tightly to his father’s back as they rode beside the Papal casket down the crowded street. Even though the Great Library was closed for the week of mourning, Jakob had arranged a brief visit with a bishop his Gypsy Scouts had once saved from a bandit attack on their way to the Churning Wastes.

The books—Gods, the books, he thought. Since the Age of Laughing Madness, P’Andro Whym’s followers had gathered what knowledge they could of the Before Times. The magicks, the sciences, the arts and histories, maps and songs. They’d collected them in the library of Windwir, and the sleeping mountain village grew over time into the most powerful city in the New World.

He’d been six. He and his father had walked into the first chamber, and Rudolfo watched the books spread out as far as he could see above and beyond him. It was the first time he experienced wonder, and it frightened him.

Now the idea of that lost knowledge frightened him even more. This was a kind of wonder no one should ever feel, and he tossed back the last of the wine and clapped for more.

“What could do such a thing?” he asked quietly.

A captain coughed politely at the flap of the tent.

Rudolfo looked up. “Yes?”

“The camp is set, General.”

“Excellent news, Captain. I will walk it with you momentarily.” Rudolfo trusted his men implicitly, but also knew that all men rose or fell to the expectations of their leader. And a good leader made those expectations clear.

As the captain waited outside, Rudolfo stood and strapped on his sword. He used a small mirror to adjust his turban and his sash before slipping out into the late morning sun.

![]()

After walking the camp, encouraging his men and listening to them speculate on the demise of Windwir, Rudolfo tried to nap in his tent. He’d not slept for any measurable amount of time in nearly three days now but even with exhaustion riding him, he couldn’t turn his mind away from the ruined city.

It had been magick of some kind, he knew. Certainly the Order had its share of enemies—but none with the kind of power to lay waste so utterly, so completely. An accident, then, he thought. Possibly something the Androfrancines had found in their digging about, something from the Age of Laughing Madness.

That made sense to him. An entire civilization burned out by magick in an age of Wizard Kings and war machines. The Churning Wastes were all the evidence one could need, and for thousands of years, the Androfrancines had mined those Elder Lands, bringing the magicks and machines into their walled city for examination. The harmless tidbits were sold or traded to keep Windwir the wealthiest city in the world. The others were studied to keep it the most powerful.

The bird arrived as the afternoon wore down. Rudolfo read the note and pondered. We’ve found a talking metal man, in Gregoric’s small, pinched script.

Bring him to me, Rudolfo replied and tossed the bird back into the sky.

Then he waited in his tents to see what his Gypsy Scouts had found.

Chapter 3

Jin Li Tam

Jin Li Tam watched the commotion and wondered about the boy. He’d opened his mouth to speak after Sethbert’s embrace, but all that had come out of him was a rush of words. Muttered lines of what sounded like Whymer text. And though he couldn’t have been older than fifteen or sixteen, his tangled hair was white and his eyes were wide and wild. Of course, when Sethbert realized he couldn’t speak, he’d dismissed him to the care of one of his servants. His only interest in the boy was to hear something firsthand of his handiwork.

It turned Jin’s stomach.

Now, as the day wound down, Jin stood in the shadows and watched the scouts return dragging their nets behind them like proud fishermen. The magicks had burned out and she could see them clearly now, their dark silk clothing gray with ash, their faces and hands covered in soot. Metal twitched and gleamed in the nets they dragged.

She counted thirteen metal men in all, and the Androfrancine apprentice was with them, crouching next to them, poking and prodding them through the mesh of the nets. “We’re missing one,” he said.

“He’s down there babbling,” the scout said. “He won’t get far; I took his leg off. We’ll go back for him as soon as we’ve dropped this lot off.”

“If the Gypsies don’t get him first,” their captain said as he approached from the direction of Sethbert’s tent, his eyebrows furrowed. “They’re in the city now. Re-magick and shadow them.”

“And if they see us?”

“We’re not at war with them.” He paused and shot a worried glance back in the direction he’d come from. “Not yet anyway.”

The apprentice was untangling one of the metal men from the net. The mechoservitor clicked and shot steam out of its exhaust grate, its glassy eyes fluttering open and then closing. “Are you functional?” the apprentice asked.

“I am functional,” the metal man said.

The apprentice pointed to a nearby tent. “Go into the tent and wait there. Do not speak to anyone but me. Do you understand?”

“I understand.” The mechoservitor, tall and slender, shining in the afternoon sun despite the coating of grime and the dents and scratches along its chassis, walked to the tent.

The apprentice turned to the next, and Jin Li Tam slipped away.

![]()

She found the boy in the servants’ tents. He sat silently at a table, a plate of food growing cold in front of him. He was still dressed in the filthy robes they’d found him in, still covered with dirt and ash.

She sat across from him, and he glanced up at her.

“You should eat,” she told him. “How long has it been since you’ve eaten?”

He opened his mouth to speak, but then closed it. He shook his head, his eyes filling with tears.

She leaned in. “Can you understand me?”

He nodded.

“I can’t imagine what you’ve seen,” she said. Of course, she could imagine it. Last night, it had filled her dreams, just that briefest look at the wasted remains of Windwir. In those nightmares, Sethbert laughed with glee while dead wizards wandered the streets of that teeming city, calling down death by fire, death by lightning, death by plague. A dozen deaths or more, raining down on a city of screaming innocents until she woke up, covered in sweat.

She remembered the stories about the Age of Laughing Madness, a time of such devastation that those few who survived were driven insane. Now, Jin Li Tam wondered if perhaps this boy had met a similar fate.

But he didn’t have the eyes of a madman. Full of sorrow and despair, yes. But not madness. She knew that look all too well these days.

Jin Li Tam looked around the tent to be sure no one listened. “Sethbert wants you to tell him what you saw,” she said in a low voice. “He wants to hear how Windwir fell, but not for any noble purpose. Do you understand?”

The boy’s face said he didn’t, but he nodded.

“Your story is what you are worth to him. As long as he thinks you are willing to tell it, he will keep you alive and well cared for.” Jin Li Tam reached a hand across the table to cover the boy’s hand. “If he thinks you cannot or will not tell it, he will discard you. Living or dead, I do not know, but he is not a kind man.” She squeezed his hand. “He is a dangerous man.”

She stood up and whistled for a servant.

A heavyset woman appeared in the doorway of the tent. “Yes, Lady?”

“A guest should not be sat to table in his own filth. Clean this boy up and find him fresh clothing.”

“I offered him bathing water, Lady, but he declined.”

Jin Li Tam let the anger edge her voice. “Surely you have children?”

“Yes, Lady. Three.”

She willed her words to soften. “Then you know how to bathe a child.”

“I do, Lady.”

Jin Li Tam nodded once, curtly. “This boy has seen more darkness and despair than any have seen since the Age of Laughing Madness. Be kind to him, and pray that you never see what he has seen.”

Then Jin Li Tam left the tent, knowing she could wait no longer. She’d put it off the last two days, uncertain of the best route. But now she knew there was no chance of her staying. There were coops of message birds scattered throughout the camp. She would find a bird that would not be missed for at least another day. She would fling it at the sky with her simple message, tied with the black thread of danger:

Windwir lies in ruin. Sethbert has betrayed us all.

And after, she would sleep with a pouch of magicks beneath her pillow, ready to flee at a word.

Rudolfo

Rudolfo’s Gypsy Scouts found the metal man sobbing in an impact crater deep in the roiling smoke and glowing ruins of Windwir. He crouched over a pile of blackened bones, his shoulders chugging and his bellows wheezing, his helmetlike head shaking in his large metal hands. They approached him silently, ghosts in a city of ghosts, but the metal man still heard and looked up.

Gouts of steam shot from his exhaust grate. Boiling water leaked from his glassy jeweled eyes. Nearby lay a mangled metal leg.

“Lla meht dellik ev’I,” the metal man said.

The Gypsies dragged him to Rudolfo because he could not stand on his own and refused to be supported. Rudolfo, from his tents outside the ruins, watched them return just like the message bird had promised.

They dragged the metal man into the clearing and released him, dropping the leg as well. Their bright colored tunics, cloaks and breeches were gray with ash and black from charcoal. The metal man gleamed in the afternoon sun.

They bowed and waited for Rudolfo to speak. “So this is all that’s left of the Great City of Windwir?”

To a man, they nodded. Slow, deliberate nods.

“And the Androfrancine Library?”

One of the Gypsy Scouts stepped forward. “Ashes, Lord.” The scout stepped back quickly, head bowed.

Rudolfo turned to the metal man. “And what do we have here?” He’d seen mechanicals before. Small ones, though, nothing quite so elaborate as a man. “Can you speak?”

“Llew etiuq kaeps nac I,” the metal man said.

Rudolfo looked again to his Gypsy Scouts. The same scout who’d spoken earlier looked up. “He’s been talking since we found him, Lord. It’s no language we’ve ever heard.”

Rudolfo smiled. “Actually, it is.” He turned back to the metal man. “Sdrawkcab kaeps,” he told him.

A pop, a clunk, a gout of steam. The metal man looked up at Rudolfo, at the smoke-filled sky and the blackened horizon that was once the world’s largest city. He shook and shuddered. When he spoke, his voice carried a depth of lament that Rudolfo had only heard twice before. “What have I done?” the metal man asked, his breast ringing as he beat it with his metal fist. “Oh, what have I done?”

![]()

Rudolfo reclined on silk cushions and drank sweet pear wine, watching the sunset wash the metal man red. His own personal armorer bent over the mechanical in the fading light, wiping sweat from his brow while working to reattach the mangled leg.

“It’s no use, Lord,” the metal man said.

The armorer grunted. “It’s nowhere close to good but it will serve.” He pushed himself back, glancing up at Rudolfo.

Rudolfo nodded. “Stand on it, metal man.”

The metal man used his hands to push himself up. The mangled leg would not bend. It sparked and popped but held as he stood.

Rudolfo waved. “Walk about.”

The metal man did, jerking and twitching, using the leg more as a prop.

Rudolfo sipped his wine and waved the armorer away. “I suppose now I should worry about escape?”

The metal man kept walking, each step becoming more steady. “You wish to escape, Lord? You have aided me. Perhaps I may aid you?”

Rudolfo chuckled. “I meant you, metal man.”

“I will not escape.” The metal man hung his head. “I intend to pay fully for my crimes.”

Rudolfo raised his eyebrows. “What crimes are those, exactly?” Then, remembering his manners but not sure if they extended to mechanicals, he pointed to a nearby stool. “Sit down. Please.”

The metal man sat. “I am responsible for the razing of Windwir and the genocide of the Androfrancines, Lord. I do not expect a trial. I do not expect mercy. I expect justice.”

“What is your name?”

The metal man’s golden lids flickered over his jeweled eyes in surprise. “Lord?”

“Your name. What is your name?”

“I am Mechoservitor Number Three, catalog and translations section.”

“That’s no name. I am Rudolfo. Lord Rudolfo of the Ninefold Forest Houses to some. General Rudolfo of the Wandering Army to others. That Damned Rudolfo to those I’ve bested in battle or in bed.”

The metal man stared at him. His mouth-shutters clicked open and closed.

“Very well,” Rudolfo finally said. “I will call you Isaak.” He thought about it for a moment, nodded, sipped more wine. “Isaak. Tell me how exactly you managed to raze the Knowledgeable City of Windwir and single-handedly wipe out the Androfrancine Order?”

“By careless words, Lord, I committed these crimes.”

Rudolfo refilled his glass. “Go on.”

“Are you familiar, Lord, with the Wizard Xhum Y’Zir?”

Rudolfo nodded.

“The Androfrancines found a cache of parchments in the Eastern Rises. They bore a striking resemblance to Y’Zir’s later work including his particular blend of Middle Landlish and Upper V’Ral. Even the handwriting matched.”

Rudolfo leaned forward, one hand stroking his long mustache. “These weren’t copies?”

The metal man shook his head. “Originals, Lord. Naturally, they were brought back to the library. They assigned the translation and cataloging to me.”

Rudolfo picked a honeyed date out of a silver bowl and popped it into his mouth. He chewed around the pit, spitting it into a silk napkin. “You worked in the library.”

“Yes, Lord.”

“Continue.”

“One of the parchments contained the missing text for Xhum Y’Zir’s Seven Cacophonic Deaths—”

Here Rudolfo’s breath rushed out. He felt the blood flee so quickly from his face that he tingled. He raised his hand and fell back into the cushions. “Gods, a moment.”

The metal man, Isaak, waited.

Rudolfo sat back up, drained off the last of his wine in one swallow and refilled the glass. “The Seven Cacophonic Deaths? You’re sure?”

The metal man shook in one great sob. “I am now, Lord.”

A hundred questions flooded Rudolfo. Each shouted to be asked. He opened his mouth to ask the first but closed it when Gregoric, the First Captain of his Gypsy Scouts, slipped into the tent with a worried expression on his face.

“Yes?” he asked.

“General Rudolfo, we’ve just received word that Overseer Sethbert of the Entrolusian City States approaches.”

Rudolfo felt anger rise. “Just?”

Gregoric paled. “Their scouts are magicked, Lord.”

Rudolfo leaped to his feet, reaching for his thin, long sword. “Bring the camp to Third Alarm,” he shouted. He turned on the metal man. “Isaak, you will wait here.”

Isaak nodded.

Then General Rudolfo of the Wandering Army, Lord of the Ninefold Forest Houses, raced from the tent bellowing for his armor and horse.

Petronus

Petronus sat before his small fire and listened to the night around him. He’d ridden the day at a measured pace, not pushing his old horse faster or farther than it needed. He’d finally stopped and made camp when the sky purpled.

Not far off, a coyote bayed and another joined in. Petronus sipped bitterroot tea with a generous pinch of Holga the Bay Woman’s herbal bone-ache remedy boiled into it. It washed the old man in warmth deeper than the dancing flames could touch.

He watched the northwest. The smoke had largely dissipated throughout the day. By now, he thought, Rudolfo and Sethbert would both be there with their armies, ready to assist if there was anyone or anything left to help.

Of course, he doubted they would find anything and he suspected he knew why. The longer he thought about it, the more sure the old man became. And each league that carried him closer to Windwir paralleled an inner journey across the landscape of his memory.

![]()

“We’ve found another Y’Zir fragment, Father,” Arch-Scholar Ryhan had said during the private portion of the Expeditionary Debriefing.

Petronus was forty years younger then, more of an idealist, but even then he’d known the risk. “You’re certain?”

The arch-scholar sipped his wine, careful not to spill it on the white carpets of Petronus’s office. “Yes. It is a nearly perfect fragment, with overlap between the Straupheim parchment and the Harston letter. It’s only a matter of time before we have the entire text.”

Petronus felt his jaw clench. “What precautions are you taking?”

“We’re keeping all of the parchments separate. Under lock and guard.”

Petronus nodded. “Good. They’re not safe even for cataloging and translation.”

“For now, yes,” Ryhan said. “But young Charles, that new Acolyte of Mechanics from the Emerald Coasts, thinks he’s found a way to power the mechoservitor he’s reconstructed using firestones. He says according to Rufello’s Notes and Specifications, these mechanicals can be erased after a day’s work, told in advance what to do and what to say, and given even the most complex instructions.”

Petronus had seen the demonstration. They’d needed a massive furnace to generate the power, but for three minutes, Charles had asked the blocky, sharp-cornered metal man he’d built to move his hands, to recite scripture and to answer complex mathematical equations for the Pope and his closest advisors. Another secret they had mined from the days before that they would keep close to their hearts, releasing it to the world when they felt it was ready for the knowledge.

“They could read it,” the arch-scholar said. “Under careful instruction. If Charles is right, a mechoservitor could even be instructed to summarize the text without out reproducing it verbatim.”

“If all of the parchments were ever found . . .” Petronus let the words trail off. He shook his head. “We’d do better to just destroy what we’ve found,” Petronus said. “Even a metal puppet dances on a human string.”

The look on the arch-scholar’s face when he said that was the beginning of Petronus’s self-inflicted slide away from Androfrancine grace.

![]()

Coyote song brought Petronus back from the past. The fire was burning down now and he pushed more wood onto it. His fists went white as he clenched them and looked to the northwest again.

They had found the fragments of Xhum Y’Zir’s spell.

They had not been careful.

They had unleashed Death upon themselves.

And if Petronus was right about the power of those words, there was nothing left of all their labor. The Androfrancines had spent two thousand years grave-robbing from the Former World and there would be precious little now to show for it.

The rage of P’Andro Whym fell upon him and Petronus bellowed at the sky.

Neb

Your story is what you are worth to him.

The redheaded woman’s words stayed with Neb long after she said them.

He’d bathed himself, waiting until the serving woman who brought the water saw him tugging at his filthy robes. The ash and dirt from his body turned the water a deep brown as soon as he settled into it. When he dried himself with the rough army towels, he saw even more ash had turned the white cotton a light gray. Still, he was cleaner than he’d been.

The robes they’d brought him were too large, but he cinched the rope belt tighter and then dumped his own wash water into the patch of ferns behind the tent.

After, he’d tried to nibble at a bit of bread, but his stomach soured after a few bites. Clutching his two books, Neb curled himself onto the cot. He thought about the redheaded woman’s words and wondered what made his story so valuable to the Overseer. And why had he seemed so flustered when he learned that Neb couldn’t speak? Worse, why had he seemed so excited to hear it in the first place? He knew the lady might tell him if he could ask her, but he also wasn’t sure he wanted to know.

Eventually, he rolled over and tried to sleep. But when he closed his eyes, there was no dark, never any dark. It was fire—green fire—falling like a giant fist onto the city of Windwir, and lightning—white and sharp—slicing upward at the sky. Buildings fell. The smell of burning meat—cattle and people alike—filled his nose. And there, in the gate down by the river docks, a lone figure rushing out, ablaze and screaming.

Of course, Neb knew his own mind was drawing that part of the picture in. But in his mind, he could see right to the melting whites of his father’s eyes, could see the blame and disappointment there.

Eventually, he gave up on the cot. Instead, he slipped out into the night and went to the cart that, true to their words, the Delta Scouts had brought back. Crawling into the back of it, nestled down among the sacks of mail and books and clothing, Neb fell into sleep.

But his dreams were full of fire.

Chapter 4

Rudolfo

Battlefields, Rudolfo thought, should not require etiquette, nor be considered affairs of state.

He remained mounted at the head of his army while his captains parleyed with the Overseer’s captains in a moonlit field between the two camps. On the horizon, Windwir smoldered and stank. At last, they broke from parley and his captains returned.

“Well?” he asked.

“They also received the birds and came to offer assistance.”

He sneered. “Came to peck the corpses clean more likely.” Rudolfo had no love for the City States, hunkered like obese carrion birds at the delta of the Three Rivers, imposing their tariffs and taxes as if they owned those broad, flat waters and the sea they spilled into. He looked at Gregoric. “And did they share with you why they broke treaty and magicked their scouts at time of peace?”

Gregoric cleared his throat. “They thought that perhaps we had ridden against Windwir and were honoring their kin-clave. I took the liberty of reminding them of our own kin-clave with the Androfrancines.”

Rudolfo nodded. “So when do I meet with the tremendous sack of moist runt droppings?”

His other captains laughed quietly behind their hands. Gregoric scowled at them. “They will send a bird requesting that you dine with the Overseer and his lady.”

Rudolfo’s eyebrows rose. “His lady?”

Perhaps, he thought, it would not be so ponderous after all.

![]()

He dressed in rainbow colors, each hue declaring one of his houses. He did it himself, waving away assistance but motioning for wine. Isaak sat, unspeaking and unmoving, while Rudolfo wrapped himself in silk robes and scarves and sashes and turban.

“I have a few moments,” he told the metal man. “Tell more of your story.”

Light deep in those jeweled eyes sparked and caught. “Very well, Lord.” A click, a clack, a whir. “The parchment containing the missing text of Xhum Y’Zir’s Seven Cacophonic Deaths came to me for cataloging and translation, naturally.”

“Naturally,” Rudolfo said.

“I worked under the most careful of circumstances, Lord Rudolfo. We kept the new text isolated in a secure location with no danger of the missing words being added to complete the incantation. I was the only mechoservitor to work with the parchment and all knowledge of my previous work with prior fragments was carefully removed.”

Rudolfo nodded. “Removed how?”

The metal man tapped his head. “It’s . . . complex, Lord. I do not fully understand it myself. But the Androfrancines write metal scrolls and those metal scrolls determine our capacity, our actions, our inactions, our memories.” Isaak shrugged.

Rudolfo studied three different pairs of soft slipper. “Go on.”

The metal man sighed. “There is not much more to tell. I cataloged, translated and copied the missing text. I spent three days and three nights with it, calculating and recalculating my work. In the end, I returned to Brother Charles to have the memory of my work expunged.”

A sudden thought struck him, and Rudolfo raised a hand, unsure why he was so polite with the mechanical. “Is memory of your work always removed?”

“Seldom, actually. Only when the work is of a sensitive or dangerous nature, Lord.”

“Remind me to come back to this question later,” Rudolfo said. “Meanwhile, continue. I must leave soon.”

“I put the parchment in its safe, left the catalog room and watched the Androfrancine Gray Guard lock it behind me. I returned to Brother Charles, but his study was locked. I waited.” The metal man whirred and clicked.

Rudolfo selected a sword in an intricate scabbard, thrusting it through his sash. “And?”

The metal man began to shake. Steam poured out of his exhaust grate. His eyes rolled and a high pitched whine emanated from somewhere deep inside.

“And?” Rudolfo said, sharpness creeping into his voice.

“And all went blank for a moment, Lord. My next memory was standing in the city square, shouting the words of the Seven Cacophonic Deaths—all of the words—into the sky. I tried to stop the utterance.” He sobbed again, his metal body shuddering and groaning. “I could not stop. I tried but could not stop.”

Rudolfo felt the mechanical’s grief, sharp and twisting, in his stomach. He stood at the flap of his tent, needing to leave and not knowing what to say.

The metal man continued. “Finally, I reversed my language scroll. But it was too late. The Death Golems came. The Plague Spiders scuttled. Fire fell from sulfur clouds. All seven deaths.” He sobbed again.

Rudolfo stroked his beard. “And why do you think this happened?”

The metal man looked up, shaking his head. “I don’t know, Lord. Malfunction, perhaps.”

“Or malfeasance,” Rudolfo said. He clapped and Gregoric appeared, slipping out of the night to stand by his side. “I want Isaak here under guard at all times. No one talks to him but me. Do you understand?”

Gregoric nodded. “I understand, General.”

Rudolfo turned to the metal man. “Do you understand as well?”

“Yes, Lord.”

Rudolfo leaned over the metal man to speak quietly in his ear. “Take courage,” he said. “It is possible that you were but the tool of someone else’s ill will.”

Isaak’s words, quoted from the Whymer Bible, surprised him. “Even the plow holds love for splitting the ground; and the sword grief for spilling the blood.”

Rudolfo’s fingers lightly brushed a polished shoulder. “We’ll talk more when I return.”

Outside, the sky grayed in readiness for morning. Rudolfo felt weariness creeping behind his eyes and in the tips of his fingers. He had stolen naps here and there, but hadn’t slept a full night since the message bird’s arrival four days before, calling him and his Wandering Army south and west. After the meal, he told himself. He would sleep then.

His eyes lingered on the ruined city painted purple in the predawn light.

“Gods,” he whispered. “What an unexpected weapon.”

Jin Li Tam

Jin Li Tam hid the stolen magicks pouch in her tent. As she straightened, she heard a polite cough behind her. She spun.

The young lieutenant—the one that had brought her the horse while they were on the road—stood in the opening.

She pulled herself to full height. “Yes?”

“Lord Sethbert informs you that Rudolfo and his entourage will be arriving within the hour. The Overseer is expecting you at the banquet table.”

Jin Li Tam nodded. “Thank you. I will be there.”

The lieutenant shuffled uncomfortably, and she could tell that he wanted to say something but was unsure. “Come in from the night, Lieutenant.” She studied him. He couldn’t have been much past twenty and had the solid look of some minor Delta noble’s son, eager to make his mark in the world. She took a step closer to him, but no more because she knew her height might intimidate him, and in this case, for this moment, she wanted his trust. “You wish to say something?”

His eyes moved around the room and he twisted his cap in his hands. “I wish to ask a question.” The words came out slowly, then sped up. “But I’m not sure I want to know.”

“I may not want to tell you,” she said. “But you may ask.”

“Some of the men have heard the Overseer talking to his generals over the last two days. Others have overheard the scouts. They say there’s nothing left of Windwir but for those metal men and that boy.”

“That seems to be true enough,” Jin Li Tam said. “Though I hope it will be proven false.”

He’s not come to it yet, she thought. There’s more he wants to ask, but he’s not sure he can trust me. She took a risk and used the subverbal finger language of the Delta Houses.

You can trust me, she signed.

He blinked. You know our signing?

She nodded. “I do.” Even as her mouth formed the words, her hands kept moving. Ask what you will, Lieutenant.

His hands fumbled with the hat and he pulled it back onto his head. “It wouldn’t be proper for me to question.” But his hands now moved too. They tell us that the Overseer had advance knowledge of Windwir’s doom from spies in the city; that we rode out to her aid by way of kin-clave. His hands went limp and she understood. This young man was on the edge of the blade now.

“You’re right,” she said. “It would not be proper. He is the Overseer. You are his lieutenant. I am his consort.” The Overseer did have advance knowledge, she signed back.

“I’m sorry to have bothered you, Lady.” And his hands again: The men have heard him boasting. They say he claims he brought down the Androfrancine city.

“Please let the Overseer know that I will join him for dinner shortly.” Jin Li Tam hesitated. Confirming his fears could lead him down a dangerous path. It was easier to be uncertain than it was to pretend a noble cause or to bury his uniform and flee. The Overseer’s boasting is true, she finally signed. She watched the color leave his face.

The lieutenant swayed and he dropped his hands. “He must have had good reason,” he whispered.

Jin Li Tam stepped closer, now revealing her height as she put her hand on the young man’s shoulder. “Once you see the Desolation of Windwir,” she said in a low voice, “you’ll know there could be no good reason for what the Overseer has done.”

The lieutenant swallowed. “Thank you, Lady.”

She nodded once, then turned away and waited for him to leave. Once he was gone, she closed the flap to her tent, hid the magick pouch in a different location, and laid out her clothing for the night’s event.

As she brushed her hair, she wondered if her father were right about Lord Rudolfo. It was clear now that she must leave sooner rather than later. Sethbert rode a slippery slope on a blind stallion, and no good could come of it. She wondered what her father would say, and she thought perhaps he would tell her to go to Rudolfo. A strategic alliance with the Ninefold Forest Houses—at least until she could return safely to the Emerald Coasts—could keep her about her father’s business a while longer.

![]()

Sethbert no longer stood when she entered a room. In the early days he had, of course, and certainly during formal occasions he followed the proper courtesies. But he was alone now with his metal man and he was chuckling as it hopped on one foot and juggled plates for him.

“Lord Overseer,” she said in the doorway, curtsying.

He looked her over, licking his lips. “Lady Jin Li Tam. You look lovely as always.”

As she walked into the room and took her seat, he waved off the metal man. “Wait in the kitchen,” he told it.

It nodded and shambled off, clicking and hissing.

“The newer ones are much better,” he said. “I think I’ll replace him.”

Jin smiled and nodded politely.

“And how are you this evening? Have you kept busy?” Sethbert seemed jovial now.

“I have, Lord. I checked on the boy and made sure he was well cared for.” When Sethbert frowned, she continued. “I’m sure he’ll be talking in no time.”

The momentary storm passed from his face. “Good, good. I will want to hear his story.”

Jin placed her hands in her lap. “Should I be aware of anything this evening, Lord?”

Sethbert smiled. “You’ve not met Rudolfo before.”

She shook her head. “I’ve not.”

“He’s a fop. A dandy of sorts.” Sethbert leaned in. “He has no children. He has no wife nor consort. I think he’s—” He waved his fingers in a feminine way. “But he’s a great pretender. If he asks you to dance—and I suspect he will—dance with him no matter how distasteful it may be.”

“If my lord wishes.”

“I do wish it.” He leaned in. “It goes without saying that the time is not right for him to know of my role in Windwir’s fall. He’ll know soon enough, but when he does it will be too late for him.”

Jin Li Tam nodded. It was sound strategy. The attack on Windwir had knocked a crutch out from under the Entrolusian economy—Sethbert might be mad, but not so mad as to be foolish. For whatever reason he’d destroyed this city, he intended to supplement the Delta’s losses by annexation, and the Ninefold Forest Houses were ripe fruit, albeit high on the tree and a bit out of the way. A small kingdom of forest towns surrounded by vast resources. The army, she realized, had never been for Windwir. “I understand.”

There was a commotion outside. The tent flaps fluttered and her young lieutenant stood in the doorway. Their eyes met briefly before he looked away.

“Lord Rudolfo rides for the camp. He’s bringing his Gypsy Scouts. They are unmagicked.”

Sethbert smiled. “Thank you, Lieutenant. Make sure he is announced appropriately.”

Jin Li Tam straightened her skirt, pulled at her top and wondered how this last meal as Sethbert’s consort would go.

Chapter 5

Rudolfo

Sethbert did not meet him at the edge of his army; instead, Rudolfo rode in escort to the massive round tent. He snapped and waved and flashed hand-signs to his Gypsy Scouts, who slipped off to take up positions around the pavilion.

Sethbert rose when he entered, a tired smile pulling at his long mustache and pockmarked jowls. His lady rose, too, tall and slim, draped in green riding silks. Her red hair shone like the sunrise. Her blue eyes flashed an amused challenge and she smiled.

“Lord Rudolfo of the Ninefold Forest Houses,” the aide at the door announced. “General of the Wandering Army.”

He entered, handing his long sword to the aide. “I come in peace to break bread,” he said.

“We receive you in peace and offer the wine of gladness to be so well met,” Sethbert replied.

Rudolfo nodded and approached the table.

Sethbert clapped him on the back. “Rudolfo, it is good to see you. How long has it been?”

Not long enough, he thought. “Too long,” he said. “How are the cities?”

Sethbert shrugged. “The same. We’ve had a bit of trouble with smugglers but it seems to have sorted itself out.”

Rudolfo turned to the lady. She stood a few inches taller than him.

“Yes. My consort, the Lady Jin Li Tam of House Li Tam.” Sethbert stressed the word “consort” and Rudolfo watched her eyes narrow slightly when he said it.

“Lady Tam,” Rudolfo said. He took her offered hand and kissed it, his eyes not leaving hers.

She smiled. “Lord Rudolfo.”

They all sat and Sethbert clapped three times. Rudolfo heard a clunk and a whir from behind a hanging tapestry. A metal man walked out, carrying a tray with glasses and a carafe of wine. This one was older than Isaak, his edges more boxlike and his coloring more copper.

“Fascinating, isn’t he?” Sethbert said while the metal man poured wine. He clapped again. “Servitor, I wish the chilled peach wine tonight.”

The machine gave a high-pitched whistle. “Deepest apologies, Lord Sethbert, but we have no chilled peach wine.”

Sethbert grinned, then raised his voice in false anger. “What! No peach wine? That is inexcusable, servitor.”

More whistling and a series of clicks. A gout of steam shot out of the exhaust grate. “Deepest apologies, Lord Sethbert—”

Sethbert clapped again. “Your answer is unacceptable. You will find me chilled peach wine even if you must walk all the way to Sadryl and back with it. Do you understand?”

Rudolfo watched. The Lady Jin Li Tam did not. She fidgeted and worked hard to hide the embarrassment in the redness of her cheeks, the spark of anger in her eyes.

The servitor set down the tray and carafe. “Yes, Lord Sethbert.” It moved toward the tent flap.

Sethbert chuckled and nudged the lady with his elbow. “You could take lessons there,” he said. She offered a weak smile as false as his earlier anger.

Then Sethbert clapped and whistled. “Servitor, I’ve changed my mind. The cherry wine will suffice.”

The metal man poured the wine and left for the kitchen tent to check on the first course.

“What a fabulous device,” Rudolfo said.

Sethbert beamed. “Splendid, isn’t it?”

“However did you come by it?”

“It was . . . a gift,” Sethbert said. “From the Androfrancines.”

The look on Jin Li Tam’s face said otherwise.

“I thought they were highly guarded regarding their magicks and machines.” Rudolfo said, raising his glass.

Sethbert raised his own. “Perhaps they are,” he said, “with some.”

Rudolfo ignored the unsubtle insult. The metal man returned with a tray of soup bowls full of steaming crab stew. He positioned the bowls in front of each of them. Rudolfo watched the careful precision. “Truly fabulous,” he said.

“And you can get them to do most anything . . . if you know how,” Sethbert said.

“Really?”

The Overseer clapped. “Servitor, run scroll seven three five.”

Something clicked and clanked. Suddenly, the metal man spread his arms and broke into song, his feet moving lightly in a bawdy dance step while he sang, “My father and my mother were both Androfrancine brothers or so my aunty Abbot likes to say. . . .” The song went from raunchy to worse. When it finished, the metal man bowed deeply.

The Lady Jin Li Tam blushed. “Given the circumstances of our meeting,” she said, “I think that was in poor taste.”

Sethbert shot her a withering glare, then smiled at Rudolfo. “Forgive my consort. She lacks any appreciation for humor.”

Rudolfo watched her hands white-knuckling a napkin, his brain suddenly playing out potentials that were coming together. “It does seem odd that the Androfrancines would teach their servitors a song of such . . . color.”

She looked up at him. Her eyes held a plea for rescue. Her mouth drew tight.

“Oh, they didn’t teach it that song. I did. Well, my man did.”

“Your man can create scripts for this magnificent metal man?”

Sethbert spooned stew into his mouth, spilling it onto his shirt. He spoke with his mouth full. “Certainly. We’ve torn this toy of mine apart a dozen times over. We know it inside and out.”

Rudolfo took a bite of his own stew, nearly gagging on the strong sea flavor that flooded his mouth, and pushed the bowl aside. “Perhaps,” he said, “you’ll loan your man to me for a bit.”

Sethbert’s eyes narrowed. “Whatever for, Rudolfo?”

Rudolfo drained his wineglass, trying to rid his mouth of the briny taste. “Well, I seem to have inherited a metal man of my own. I should like to teach him new tricks.”

Sethbert’s face paled slightly, then went red. “Really? A metal man of your own?”

“Absolutely. The sole survivor of Windwir, I’m told.” Rudolfo clapped his hands and leaped to his feet. “But enough talk of toys. There is a beautiful woman here in need of a dance. And Rudolfo shall offer her such if you’ll be so kind as to have your metal man sing something more apropos.”

She stood despite Sethbert’s glare. “In the interest of state relations,” she said, “I would be honored.”

They swirled and leaped around the tent as the metal man sang an upbeat number, banging on his metal chest like a drum. Rudolfo’s eyes carefully traveled his partner, stealing glances where he could. She had a slim neck and slim ankles. Her high breasts pushed against her silk shirt, jiggling just ever so slightly as she moved with practiced grace and utter confidence. She was living art and he knew he must have her.

As the song drew to a close, Rudolfo seized her wrist and tapped a quick message into it. A sunrise such as you belongs in the East with me; and I would never call you consort.

She blushed, cast down her eyes, and tapped back a response that did not surprise him at all. Sethbert destroyed the Androfrancines; he means you harm as well.

He nodded, smiled a tight smile, and released her. “Thank you, Lady.”

Sethbert looked at Rudolfo through narrow eyes, but Rudolfo made a point from that moment forward of looking at the Overseer’s Lady rather than his host. Dinner passed with excruciating slowness while banter fell like a city-dweller’s footfall on the hunt. Rudolfo noticed that at no point did Sethbert bring up the destruction of Windwir or the metal man his Gypsy Scouts had found.

Sethbert’s lack of words spoke loudest of all.

Rudolfo wondered if his own did the same.

Neb

Quiet voices woke Neb from his light sleep. He lay still in the wagon, trying hard not to even breathe. The night air was heavy with the smell of smoke mingled with Evergreen.

“I heard General O’Sirus say the Overseer is mad,” one voice said.

A snort. “As if that’s anything new.”

“Do you think it’s true?”

“Do I think what’s true?”

A pause. “Do you think he destroyed Windwir?”

Neb heard the sound of cloth rustling. “More likely they destroyed themselves. You know what they say about Androfrancine curiosity. Gods only know what they found digging about in the Churning Wastes.” Neb heard the soldier draw phlegm down and spit. “Probably Old Magick . . . Blood Magick.”

For all their obstinacy toward unsanctified children, the Androfrancines did one thing for them very well. One thing that—apart from the wealthiest of the landed and lords—no one else did for their children: They gave them the best education the world could offer.