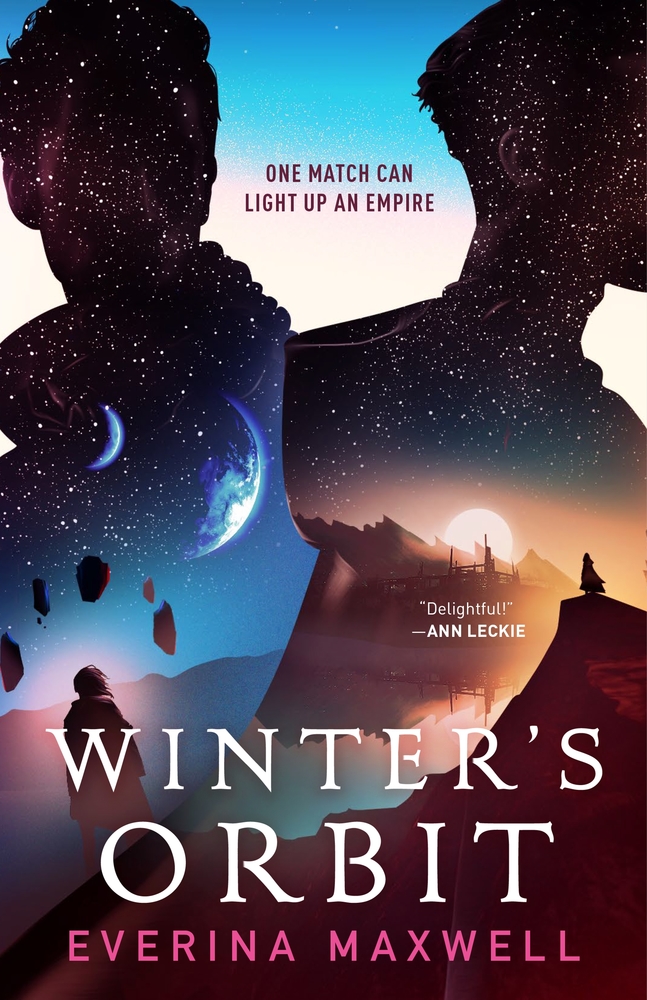

Ancillary Justice meets Red, White & Royal Blue in Winter’s Orbit, Everina Maxwell’s gut-wrenching and romantic debut.

Ancillary Justice meets Red, White & Royal Blue in Winter’s Orbit, Everina Maxwell’s gut-wrenching and romantic debut.

A famously disappointing minor royal and the Emperor’s least favorite grandchild, Prince Kiem is summoned before the Emperor and commanded to renew the empire’s bonds with its newest vassal planet. The prince must marry Count Jainan, the recent widower of another royal prince of the empire.

But Jainan suspects his late husband’s death was no accident. And Prince Kiem discovers Jainan is a suspect himself. But broken bonds between the Empire and its vassal planets leaves the entire empire vulnerable, so together they must prove that their union is strong while uncovering a possible conspiracy.

Their successful marriage will align conflicting worlds.

Their failure will be the end of the empire.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of Winter’s Orbit, on sale 02/02/2021.

Chapter 1

“Well, someone has to marry the man,” the Emperor said.

She sat, severe and forbidding in a high-collared tunic, in her reception room at the heart of the warren-like sprawl of the Imperial Palace. The arching windows of the tower were heavily optimized to amplify the weak autumn sunlight from Iskan V; the warm rays that lit the wrinkled Imperial countenance should have softened it, but even the sunlight had given that up as a bad job.

Across from her, in a formal uniform that was only slightly crumpled, Kiem—Prince Royal of Iskat and the Emperor’s least favorite grandchild—had been stunned into silence. He was rarely summoned to an Imperial audience unless he’d done something spectacularly lacking in common sense, so when the Emperor’s aide had called him, he’d racked his brain for a cause but he’d come up empty-handed. He’d half wondered if it was about the Galactic delegation that had arrived yesterday and stirred up the palace. Kiem wasn’t a natural when it came to politics; maybe the Emperor wanted to warn him to stay out of the way.

This was the opposite of staying out of the way. Kiem had braced for a dressing-down, not to walk out of the room engaged to a vassal diplomat he’d never even met.

He opened his mouth to say, I don’t see why anyone has to marry him, then thought better of contradicting the Emperor and shut it again. This was how he got himself in trouble. He rephrased. “Your Majesty, Prince Taam has only been dead a month.”

It sounded awful the moment it left his mouth. Taam had been Kiem’s cousin, after all, and the Imperial family was technically still in mourning. Kiem had naturally been shocked when he heard of the flybug accident, but at the last count he’d had just over forty relatives ahead of him in the succession, mostly cousins, and he hadn’t known Taam particularly well.

The Emperor gave him a withering look. “Do you think I am unaware?” She tapped her fingertips on the lacquered surface of the low table beside her, probably giving him a second chance to remember his manners. Kiem was too disturbed to really appreciate it. “The Thean treaty must be pinned down,” she said. “We are under significant time pressure.”

“But—” Kiem said. He scrabbled for an argument as his gaze followed the movement of her fingers. The low table was crowded with official gifts, mainly from vassal planets: crystal plates, a bowl of significant mosses, a horrible gold clock from Iskat’s Parliament. Among them, under a bell jar, a small Galactic remnant glowed softly. It was a color Kiem’s eyes couldn’t process, like a shard of glass that had been spat out of another dimension. Even its presence in the room made Kiem’s brain uncomfortable. He made himself look away from it, but unfortunately that meant looking at the Emperor.

He tried again. “But, Your Majesty—marrying Taam’s partner—” He was vaguely aware of who it was. Prince Taam and Count Jainan, the Thean representative, had been one of the royal family’s more intimidatingly polished couples, like the Emperor had ordered them built in a synthesizer. Iskat bound treaties with marriages—always had, right from when the first colonists settled on the planet—and one of the unspoken reasons that Iskat had so many minor royals was to have representatives on hand when they were needed. Kiem had nothing to disqualify him: he wasn’t a parent, overly religious, opposed to monogamy, gender-exclusive, or embarrassingly hung up on someone else. That didn’t mean he could stand in for Taam, Jainan’s partner of five years. “Ma’am, surely you need someone more”—dignified—“suitable. Prince Vaile, maybe. Or no one? Forgive me, but I don’t see why we have to find him another partner.”

The Emperor regarded Kiem as if painfully reminded of the differences between him and Prince Taam. “You have not paid any attention to the political situation, then.”

Kiem rubbed a hand across his forehead unconsciously. The air in the Emperor’s rooms always felt dry and slightly too hot. “Sorry.”

“Of course not. I see you were drinking last night. At the carnival?”

“No, I—” Kiem heard himself sound defensive and stopped. He hadn’t been falling-down drunk for a long time now, but the script between him and the Emperor was apparently carved in stone from back in his student days, when every summons turned out to be an Imperial reprimand for his latest minor scandal. “I only went for the afternoon.”

The Emperor glanced at the shifting pictures in the press folder on the table. “Press Office inform me that you put on a troll costume, joined a carnival procession group, and fell in a canal in the middle of the parade.”

“It was a kids’ group,” Kiem said. He would have panicked about trying to explain the newslog photos, but he didn’t have any panic left over from being summarily engaged to a stranger. “Their troll dropped out at the last minute. The canal was an accident. Your Majesty, I—I’m”—he cast about desperately—“too young to get married.”

“You are in your mid-twenties,” the Emperor said. “Do not be ridiculous.” She rose from her seat with the careful smoothness of someone who received regular longevity treatments and crossed to the tower window. Kiem rose automatically when she did but had nothing to do, so he clasped his hands behind his back. “What do you know about Thea?”

Kiem’s spinning brain tried desperately to remember some relevant facts. Iskat ruled seven planets. It was a loose, federated empire; Iskat didn’t intervene in the internal affairs of its vassals, and the vassals in return kept their trade routes running smoothly and paid taxes. Thea was the newest and smallest member. It had been assimilated peacefully—the same couldn’t be said of all the Empire’s planets—but that had been a generation ago. It didn’t usually make the headlines, and Kiem didn’t pay much attention to politics.

“It has . . . some nice coastland?” Kiem said. All his brain could come up with were some tourist shots of green and sunny hills falling down to a cobalt-blue ocean, dredged up from some long-forgotten documentary, and a catchy snippet from a Thean music group. “I, uh, know some of its”—the Emperor didn’t listen to music groups—“popular culture?” Even he winced at hearing how that sounded. That wasn’t a basis for a relationship.

The Emperor examined him like she was trying to figure out how his parents’ genes had produced something so much less than the sum of their parts. She looked away, back to the view outside. “Come here.”

Kiem obediently crossed to the window. Below, the city of Arlusk sprawled under a snow-heavy sky, pale even through the light-optimizing glass. The grand state buildings jutted up through the city like veins of marble emerging from rock, two hundred years older than anything else in the sector, with a jumble of newer housing blocks nestled around them. The first real snow of the long winter had fallen yesterday. It was already turning to slush in the streets.

The Emperor ignored all of that. Her gaze was fixed on the far side of the city, where the spaceport spilled down the side of a mountain like an anthill. Silver flashes of shuttles came and went above it, while berthed ships were nestled in huge bays dug into the mountainside. Kiem had known the bustle of local space traffic all his life. Like most Iskaners, he’d never made the year-long journey to the far-off galactic link—the gateway to the wider galaxy—but the Empire’s vassal planets were much closer, and ships hopped between them and Iskat all the time.

One ship, hovering unsupported next to a servicing tower, gave Kiem an immediate headache. Its matte-black surface sucked in all reflection and gave off rippling shimmers that had nothing to do with the angle of the sunlight. Kiem squinted at the size of it. Nothing that big should be able to float in planetary gravity. It was nothing like the shard on the Emperor’s display table, but it was definitely weird shit that didn’t come under the normal rules of physics. He took a stab. “The Galactics?”

“Do you read nothing but tabloid logs?” the Emperor said. It seemed to be rhetorical. “That ship belongs to the Resolution. Despite its frankly absurd size, it contains one Auditor and three administration staff. It can apparently jump through links under its own power and is impervious to mass scanners. The Auditor—whom I will admit to finding deeply unsettling on a personal level—is here to legally renew the treaty between the Empire and the Resolution. Even you cannot have missed this. Tell me you know what the Resolution is.”

Kiem stopped himself from saying he didn’t actually live under a rock, even if Iskat was a year’s travel from any other sector. “Yes, ma’am. It runs the rest of the galaxies.”

“It does not,” the Emperor said sharply. “The Resolution is just that: an agreement between ruling powers. It runs the link network. Iskat and our vassals have signed our own set of Resolution terms, as have other empires and Galactic powers. As long as those are in place, we can trade through our link, keep our internal affairs to ourselves, and be certain no invading force will use the link to attack us. We are due to sign the treaty on Unification Day in just over a month. The Auditor, if all goes well, will look through our paperwork, sweep up those remnants the Resolution is so obsessed with, witness the treaty, and leave.”

Kiem blinked away from the eye-watering Resolution ship and looked at her instead. Her gnarled hand briefly touched the flint pendant at her throat in a gesture that might have been stress. Kiem couldn’t remember a time when her hair hadn’t been pure white, but she never seemed to age. She only got thinner and tougher. She was afraid, Kiem realized. He felt a sudden chill; he’d never seen her afraid.

“Got it,” he said. “Play nice with the Resolution. Give the Auditor the VIP treatment, show him what he wants, send him away again.” He made a last-ditch attempt. “But what’s that got to do with me and the Theans? Surely marriages are the last thing you want to worry about now.”

That was the wrong thing to say. The Emperor gave him a sharp, unsparing look, turned away from the window and made her way stiffly back to her chair. She smoothed out her old-fashioned tunic as she sat. “It is inevitable,” she said, “that in a family as large as ours, there are some who are more capable of handling their responsibilities than others. Given your mother’s achievements, I had higher hopes for you.”

Kiem winced. He recognized this lecture; he’d last heard it after his incident at university, just before he’d been exiled to a monastery for a month. “I apologize, ma’am.” He managed to keep quiet for all of a split second before he said, “But I still don’t understand. I know the treaties are important. But the man Thea sent—Jainan—already married Prince Taam. Just because Taam’s dead doesn’t mean the marriage didn’t happen.”

“Our vassal treaties underpin our treaty with the Resolution,” the Emperor said. “They formalize our right to speak for the Empire. The Auditor will check that all the legalities are in order. If he finds out one of our marriage links is broken, he will decree there is no treaty.”

Kiem had been too young to remember the last Galactic treaty renewal and had never bothered to learn much about the Resolution, but even he felt a vague sense of horror at the prospect of an Auditor scrutinizing something he was responsible for. The Auditors were supposed to be meticulous at finding mistakes and unnervingly detached from human concerns. He swallowed. “Yes, ma’am.”

“You do not need to be astute or political,” the Emperor said, her tone returning to normal. “You merely need to stand in the right place, mouth some words, and not offend the entire Thean press corps. Thea has recently had some internal difficulties with protests and student radicals; our political links are not as strong as we would like. A new marriage will help smooth matters over.”

“What does that mean?” Kiem said.

The Emperor’s lips thinned. “The Theans are dragging their feet on everything we ask. Our mining operation in Thean space provides valuable minerals; the Theans keep finding new ways to complain about it. At the moment I have one councilor advising me to give up and make Thea a special territory.”

“You wouldn’t,” Kiem said, shocked. Iskat only installed a special governing body if the planet was too lawless to have one of its own. Sefala was the sole special territory in the Empire, and only because it was controlled by raider gangs. “Thea has its own government.”

“I have no desire to,” the Emperor said testily. “I have very little appetite for another war, and this would be the worst possible time. Hence you will be signing a marriage contract with Count Jainan tomorrow.”

For the first time he could remember, Kiem was utterly lost for words.

“There are no legal complications,” the Emperor continued. “You are of age and acceptably close to the throne. He will—”

“Tomorrow?” Kiem blurted out. He sat down hard on the uncomfortable gilded chair. “I thought you meant in a few months! The man lost his life partner!”

“Don’t be absurd,” the Emperor said. “We have precious little time before the treaty is signed on Unification Day. Everything must be watertight by then. On top of everything else, we agreed to rotate the planet that hosts the ceremony, and twenty years ago we held it on Eisafan, so this time it will be Thea’s turn. The Thean radicals have no concept of stability. If they perceive any weakness, we can expect them to use the occasion as a focal point for discontent. The Auditor may conclude Iskat does not have sufficient control over the rest of the Empire to keep our Resolution treaty valid. There must be a representative couple in place to disprove this, with no visible concerns, smiling at the cameras. You are good at appearing confident in pictures. This should not strain your capabilities.”

Kiem clenched his fists, looking down at the floor. “Surely in a couple of months,” he said. The creases around the Emperor’s eyes started to deepen; she never reacted well to pleading. However much effort Kiem had put into sobering up, he’d never been able to hold his ground against her. He tried one last time. “Tell the Auditor we’re engaged. We can’t just force Count Jainan into this.”

“You will cease this quibbling,” the Emperor said. She came back to her desk, propped her hands on it, and leaned across. She might be elderly and slow but her gaze reached into the squishy parts of Kiem’s fear receptors like a fishhook. “You would have me break the treaty,” she said. “You would destroy our tie to the Resolution and leave us cut off from the rest of the universe. Because you do not care for duty.”

“No,” Kiem said, but the Emperor hadn’t finished.

“Jainan has already agreed. That I will say for Thea: their nobles know how to do their duty. Will you dishonor us in front of them?”

Kiem didn’t even try to hold her gaze. If she chose to make it an Imperial command, he could be imprisoned for disobeying. “Of course not,” he said. “Very happy to—to—” He stuttered to a halt. To forcibly marry someone whose life partner just died. What a great idea. Long live the Empire.

The Emperor was watching him closely. “To ensure Thea knows it is still tied to us,” she said.

“Of course,” Kiem said.

Copyright © Everina Maxwell 2021

Pre-order Winter’s Orbit Here:

I see what the publishers wanted with this rewrite, and I think we lose out. They make everything evident instead of trusting the reader to get the context by inference. The text is blunt, info-dumping, less elegant than Course of Honour, leaving too little to the imagination. Your editors are idiots.

(Shall still buy it, though, and any sequels you plan to write — that’s how much I love the world you created.)