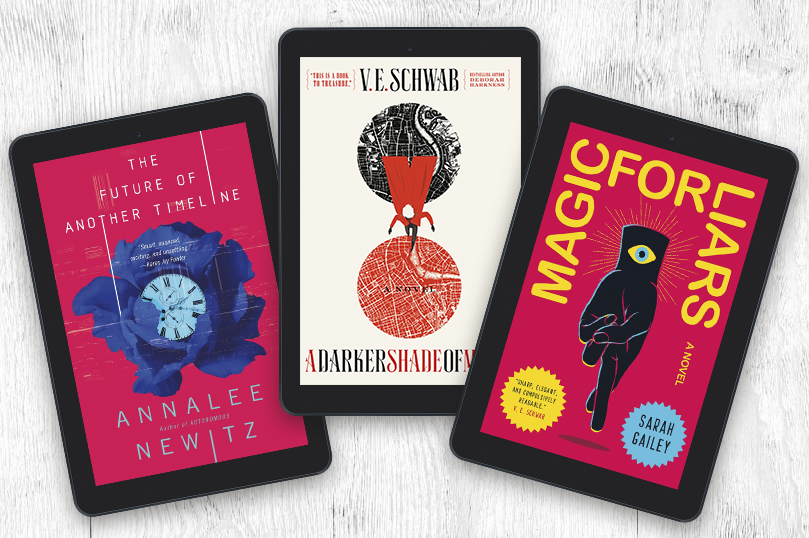

$2.99 ebook Sale: June 22-28

Happy Tuesday, everyone! We have a VERY exciting ebook sale this week for some of our bestselling titles—are you ready? Check out what books you can snag for only $2.99 here.

Happy Tuesday, everyone! We have a VERY exciting ebook sale this week for some of our bestselling titles—are you ready? Check out what books you can snag for only $2.99 here.

Here’s our list of recommendations for last minute gifts to give the fantasy fan in your life!

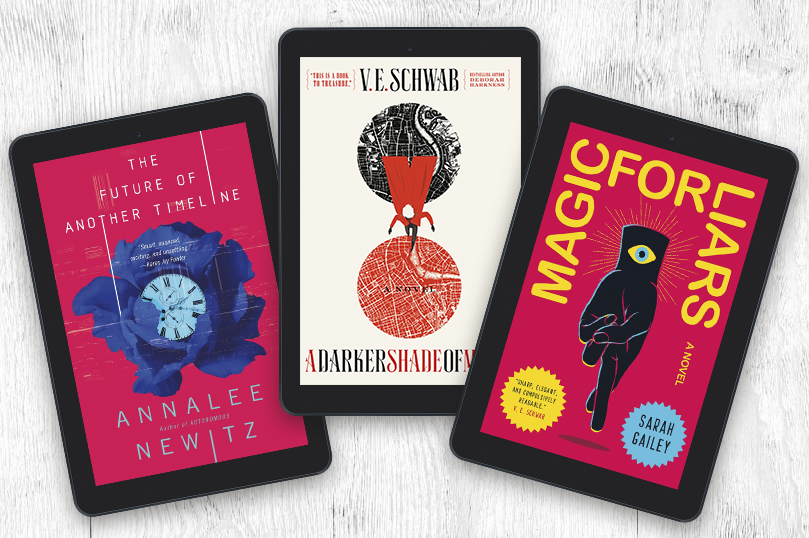

The ebook editions of Necroscope and The Burrowers Beneath by Brian Lumley are now on sale for only $2.99, perfect for some chilling Halloween reading!

Ebook editions of Tor Books finalists for the Hugo Awards are temporarily on sale for $2.99. This offer ends August 4th.

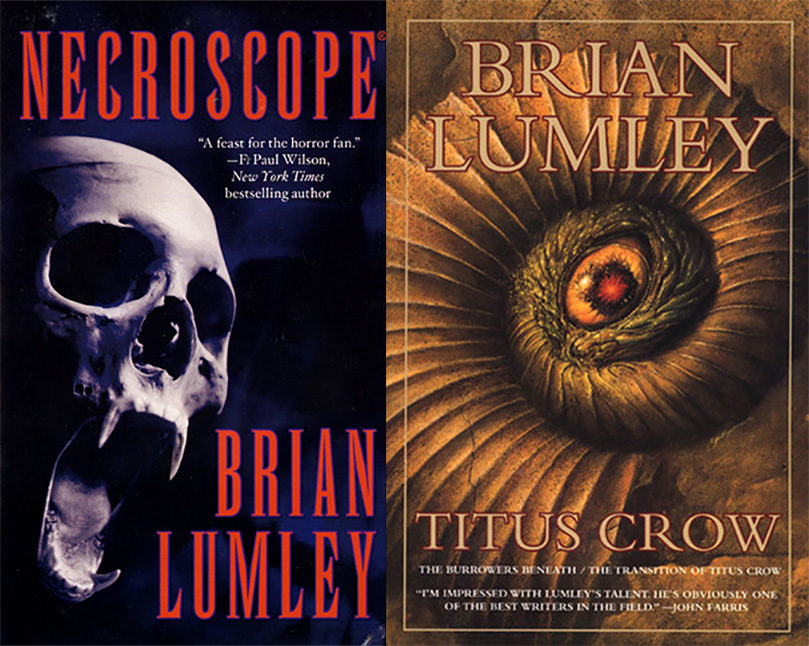

New from Allen Steele, Charlie Jane Anders, Renee Patrick, and more!

In honor of the paperback release of the Nebula Award-nominated All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders, we’re releasing a special extended excerpt.

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in April! Here is the info on all of our upcoming author events. See who is coming to a city near you! Charlie Jane Anders, All the Birds in the Sky Wednesday, April 13 The Delancey – Writers With Drinks NYC New York, NY 7:00 PM Friday, April 22…

Tor is at WonderCon in LA this weekend! See the schedule below to find out where you can find your favorite Tor authors. Friday, March 25, 2016 Getting to the Point 12:00p.m. – 1:00p.m. Room: 151 SF/F authors discuss the pointy strategic bits of weapons and battle tactics as their characters battle for causes from…

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in March! Here is the info on all of our upcoming author events. See who is coming to a city near you! Charlie Jane Anders, All the Birds in the Sky Tuesday, March 1 Google Mountain View, CA 2:30 PM R.S. Belcher, The Brotherhood of the Wheel Thursday, March…

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in February! Here is the info on all of our upcoming author events. See who is coming to a city near you! Charlie Jane Anders, All the Birds in the Sky Thursday, February 4 Skylight Books Los Angeles, CA 7:30 PM Tuesday, February 23 Green Apple Books San Francisco,…