How many syllables was that again, or, “Can I buy a vowel?”

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues with a guest post on the difficulty of names (and names, and names) in a fantasy novel like Crown of Vengeance.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues with a guest post on the difficulty of names (and names, and names) in a fantasy novel like Crown of Vengeance.

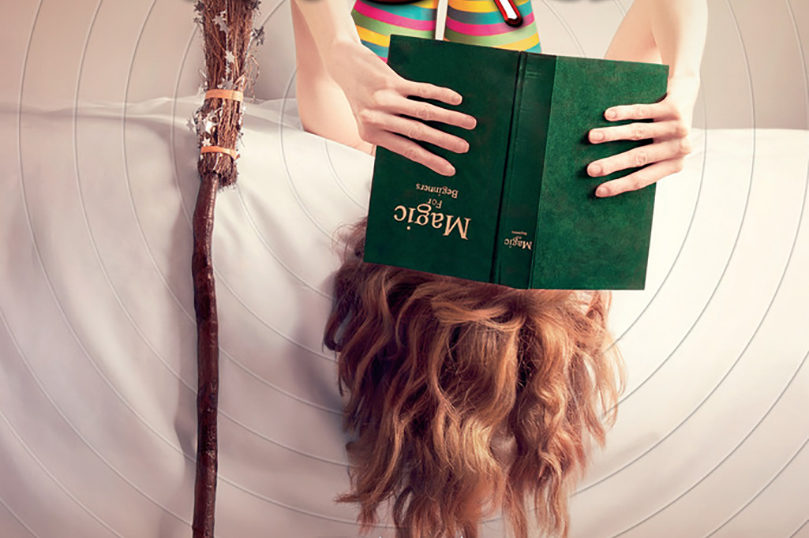

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from Seriously Wicked by Tina Connolly, about a reluctant young witch named Camellia whose mother is – well – seriously wicked.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Way of Kings, the first book in Brandon Sanderson’s sweeping epic fantasy series The Stormlight Archive.

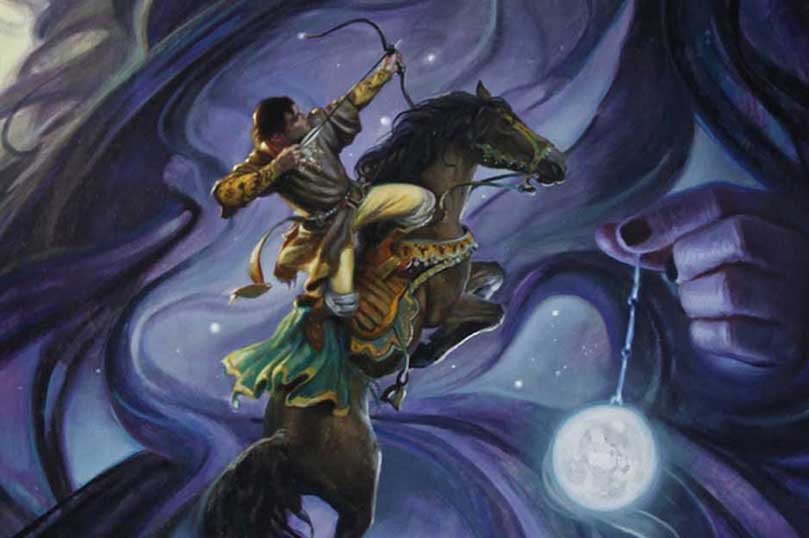

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues with a guest post from Elizabeth Bear, author of the Eternal Sky series beginning with Range of Ghosts (and many other works of fantasy and science fiction), about the esoteric practices that make a successful writer.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Eterna Files, a gaslamp fantasy about the quest to find the secret to immortality.

Start reading a new fantasy series! This month we’re offering a chance to win five series starters on Goodreads.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an excerpt from The Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston, a historical fantasy set at the birth of the Roman Empire. Civil war rages in Rome, but it is a secret war for the lost treasures of the gods that will shape the first century BC.

Our Fantasy Firsts program continues today with an ebook sale of Crown of Vengeance by Mercedes Lackey and James Mallory, on sale now for only $2.99!* A darkness is rising – and the daughter of disgraced royalty may be the land’s salvation – or its ruin.

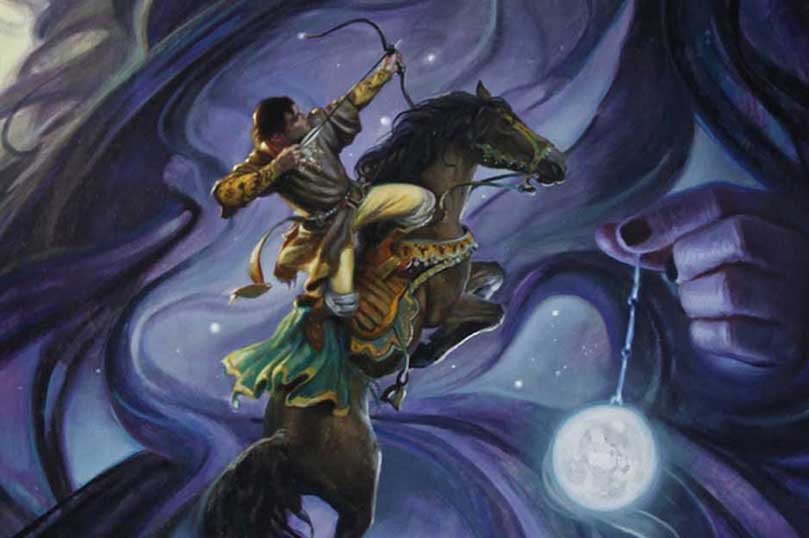

Our Fantasy Firsts program continues today with an ebook sale of Range of Ghosts by Elizabeth Bear, on sale now for only $2.99!* The Eternal Sky series follows an exiled warrior and a princess-turned-sorceress, standing against a mysterious cult pulling the strings of empires.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues with a guest post from Tom Doyle about the crypto-historical past behind the heroes of American Craftsmen.