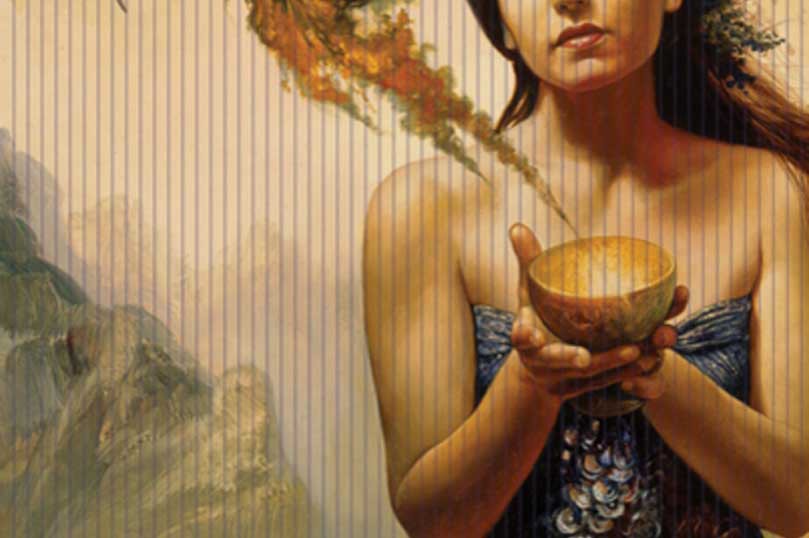

Throwback Thursdays: “Magic Calls to Magic”

Welcome to Throwback Thursdays on the Tor/Forge blog! Every other week, we’re delving into our newsletter archives and sharing some of our favorite posts. Back in November of 2010, author A.M. Dellamonica explained the rules of magic in the world she created for her story “Nevada” and novel Indigo Springs. She brings the same skills…