Digital Minds! 6 Inventive Spins on Artificial Intelligence

The fog of the future is familiar territory for writers of science fiction, so we’ve gathered five titles to provide a window into the potential futures of artificial intelligence.

The fog of the future is familiar territory for writers of science fiction, so we’ve gathered five titles to provide a window into the potential futures of artificial intelligence.

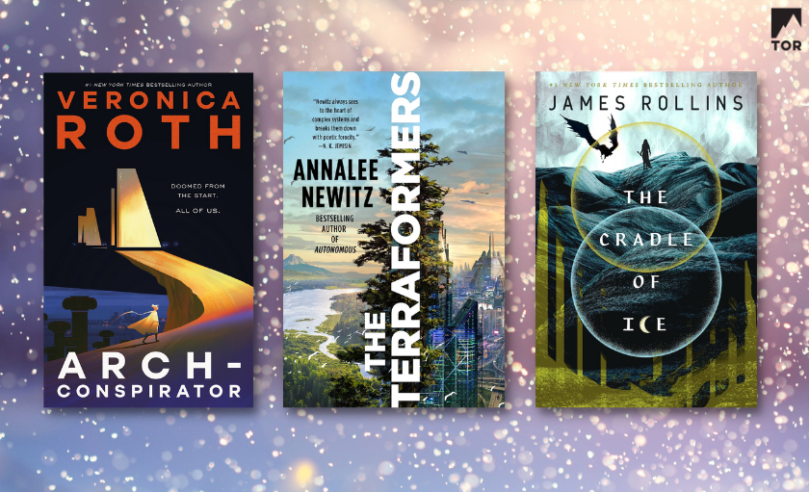

2024 is a big year with a lot of big books! Here’s all of our series that are getting a new entry this year, right here.

It’s November! As the year draws to a close in two short months, our eBook sales are just getting started. Check it out here!

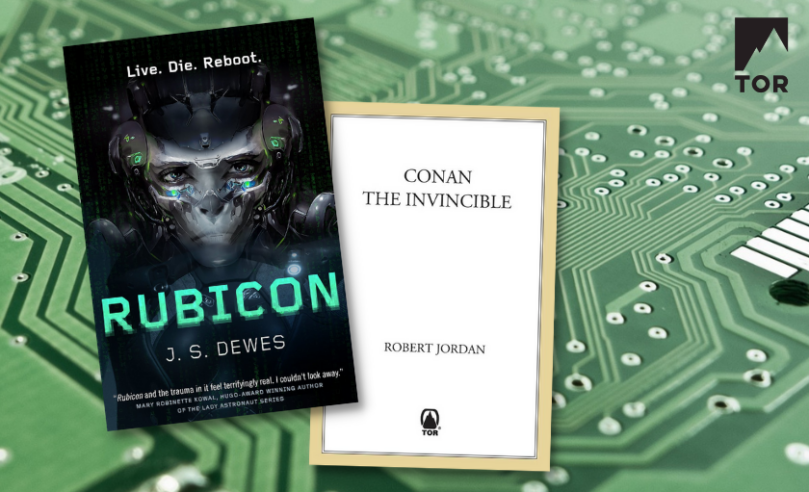

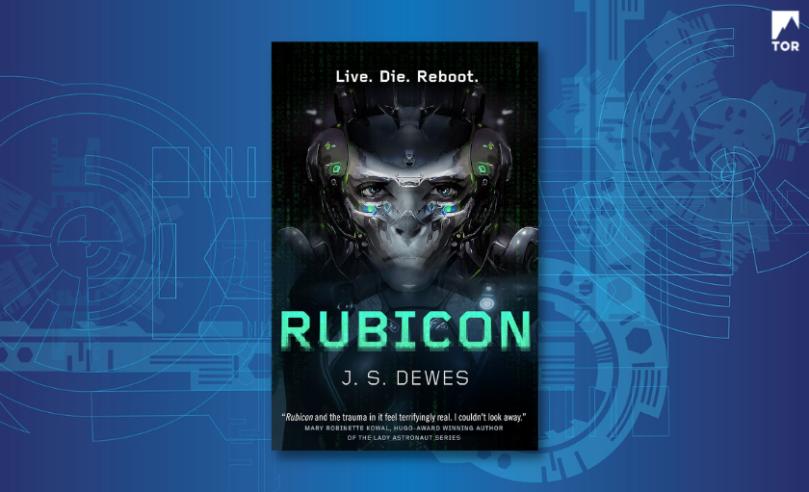

Does every book or movie HAVE to feature The Ultimate Big Bad (TM) to make it a good, entertaining piece of fiction? J. S. Dewes, author of Rubicon, joins us today to talk about some of her favorite examples of media with less tradition villains. Check it out here!

It’s a new year and that means new books to keep you warm and cozy this winter! Check out everything coming from Tor Books in Winter 2023.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of Rubicon by J. S. Dewes, on sale 3/28/23

Happy Saturday, everyone! For one day only, snag the following ebooks for only $2.99. What are you waiting for?!

Here I am, defiantly stating that coming-of-age is no longer just for kids & teens! Let’s discuss.

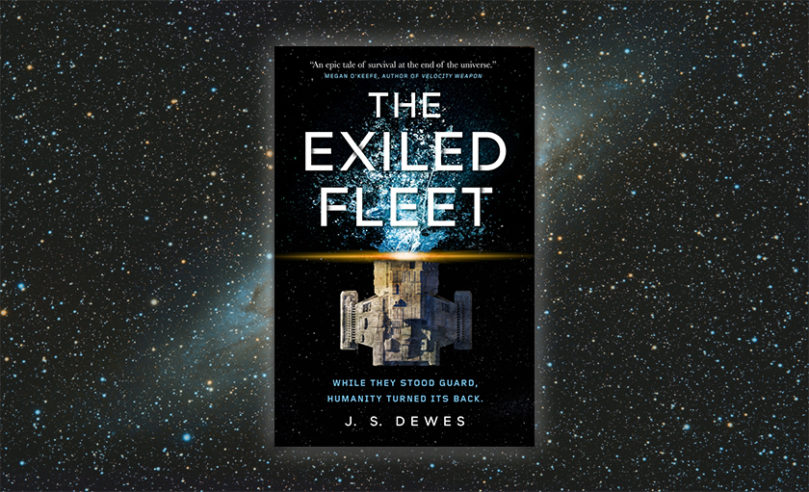

Please enjoy this free preview of The Exiled Fleet, on sale 08/17/2021.

A big THANK YOU to all our amazing friends and fans who joined us for TorCon 2021. We hope you had an amazing time and hope to see you again for our next virtual event! If you’re bummed you couldn’t make it to all of the activities, don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. You can see the recordings of almost all of TorCon PLUS some short recaps here!