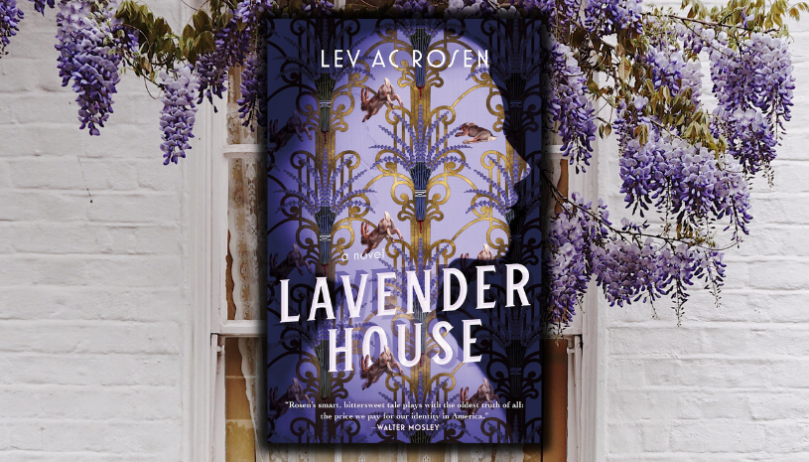

Forge Your Own Book Club: Lavender House by Lev AC Rosen

By Ariana Carpentieri: With Halloween right around the corner, ‘tis the season for murders and mysteries! We may not have a haunted house for you, but we have the next best thing: Lavender House by Lev AC Rosen, coming your way on October 18th! This deliciously intense suspense will keep you on the edge of…