opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

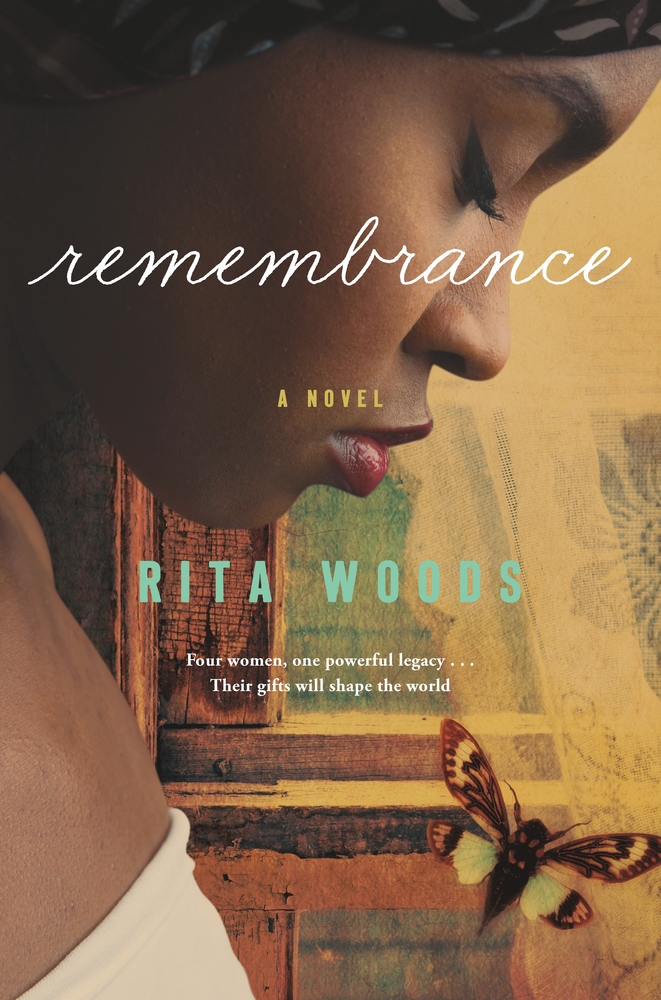

opens in a new window Remembrance…It’s a rumor, a whisper passed in the fields and veiled behind sheets of laundry. A hidden stop on the underground road to freedom, a safe haven protected by more than secrecy…if you can make it there.

Remembrance…It’s a rumor, a whisper passed in the fields and veiled behind sheets of laundry. A hidden stop on the underground road to freedom, a safe haven protected by more than secrecy…if you can make it there.

Ohio, present day. An elderly woman who is more than she seems warns against rising racism as a young woman grapples with her life.

Haiti, 1791, on the brink of revolution. When the slave Abigail is forced from her children to take her mistress to safety, she discovers New Orleans has its own powers.

1857 New Orleans—a city of unrest: Following tragedy, house girl Margot is sold just before her 18th birthday and her promised freedom. Desperate, she escapes and chases a whisper…. Remembrance.

opens in a new windowRemembrance by Rita Woods will be available on January 21. Please enjoy the following excerpt and read excerpts from Gaelle, Margot, and Abigal opens in a new windowhere, opens in a new windowhere, and opens in a new windowhere!

Winter

1852

Winter woke with a start, heart tripping wildly in her chest. The night had been filled with vaguely remembered nightmares: snarling dogs, screaming children, fire. It clung to her still, mixing with the sweat on her skin, chilling her. She kicked free of her blankets and sat up, feeling jittery and out of sorts.

Crawling from her bedding, she splashed cold water from the basin on her face, in her armpits, pausing for a moment to stare at the reflection that rippled on the water’s surface. Broad face, the color of a pine cone, hair tangled wildly about her head. She tugged at it, trying to separate the matted strands, but it was useless. With a sigh, she pushed one finger into the bowl of soda powder and quickly brushed her teeth, then pulled the cloak from the peg near the door. Wrapping it around her shoulders, she stepped into the cold fall morning.

It was barely an hour past dawn and Remembrance was already buzzing with activity. From the highlands far up in the hills that ringed the settlement, the mournful lowing of cows drifted down to her through the trees, punctuated by the high pitched ringing of Thomas’s hammer as he worked the metal in his smithy.

Remembrance.

To Winter, it was simply the place she’d grown up, the only home she’d ever known. But to everyone else who lived here, down to the last man, woman, and child, it was a place of sanctuary. A place where people like her—colored people—could live in peace and safety.

Remembrance.

A place within a place.

Spoken of with a pride mixed with disbelief. A place that should not exist, yet did. A place created by some sort of poorly understood magic. Created by Mother Abigail. Priestess. Practitioner of vodun.

Instinctively, Winter turned to look up the wide, worn trail that led to the highlands. Mother Abigail’s cabin lay nearly at the summit of one of the highest hills, just below the wide, flat clearing where the men worked a few acres of crops and their small herd of sheep and cattle grazed. The priestess’s cabin was no different than all the others in Remembrance, a simple structure of rough wood planks and river stone.

Something’s coming—something big. Something terrible.

The thought came out of nowhere, like a slap in the face, and Winter inhaled sharply as a shiver snaked up her spine. The nightmares seemed to have followed her into the daylight. Clutching her cloak, she sniffed at the air. There was an uncomfortable sensation in the center of her gut, as if the settlement was just the smallest bit off-balance.

With a soft grunt, Winter stepped onto the path, following it as it sloped gently downhill, away from Mother Abigail’s cabin. The air was clean, crisp, the trees glowing scarlet and gold in the muted sunlight. The damp earth felt wonderfully cold beneath her bare feet. She waded into a mound of leaves, inhaling the scent of forest and earth, just as Will, the blacksmith’s younger son, passed her, heading toward the highlands. The boy grinned, shaking his head at the sight of her standing shin-deep in wet leaves. By the time she reached the trailhead and entered the clearing for the Central Fire, the feeling of foreboding was fading.

A handful of women still hovered near the fire circle. They nodded but didn’t speak as they quickly rearranged the firewood near the canning shed before disappearing, laughing, down a narrow path through the woods. It was washday, and most of the women of Remembrance would spend it down at the creek washing the bed linens and clothes.

It was peculiar to be alone at the Central Fire, the massive fire circle that marked the very core of Remembrance. It was where the settlers gathered for meals and fellowship, for announcements and celebrations, but the effort it took to keep Remembrance running smoothly, the urgency of chores to be done, especially now, in preparation against the coming winter, had scattered the settlers to their tasks. Everyone had their job to do in Remembrance. Everyone except her.

Despite the fact that she had been in Remembrance longer than anyone aside from Mother Abigail, despite the fact that Remembrance was her only home, somehow she drifted just outside the beating heart of the settlement, circling round and round but never quite absorbed into its soul.

The ex-slaves, the men and women who had managed to find their way to the safety of Remembrance, were polite, but distant. Because she belonged to Mother Abigail? Because she was not one of them?

She had not been born here, in this place that should not even exist. She had been born out there, in the world, like them. Mother Abigail told her the story every day on the anniversary of her finding.

Her mother, her real mother—a woman whose name she would never know—had placed her in a basket and covered her with a woolen shawl, and then she had run. Run from one of those bad places Winter only knew as names in other people’s stories. Her nameless mother had looked not much older than Winter was now. Had she run from Kentucky? From Alabama? Perhaps one of those island plantations that grew rice off the coast of South Carolina. All Mother Abigail could tell her was that her mother had run, made it all the way to Remembrance, made it almost to freedom.

Except . . .

Except a freak late-spring storm had roared in off the lake. Birds froze solid to tree limbs. The sky filled with snow thunder. Mother Abigail had found them there, on the other side of the Edge, that thin boundary separating Remembrance from the outside world. Her mother was wrapped around the basket, giving her baby the last, the only thing, she had to offer—her body’s dying warmth.

“Named you Winter,” said Mother Abigail every time she told the story. “And you been mine ever since.”

Winter glanced up at the lightening sky. She was one of them. Even if she couldn’t remember the horror, the fear. The Outside had taken something from her, too.

Winter’s stomach rumbled and she moved inside the ring of logs surrounding the massive Central Fire. There, at the fire’s edge, she found a skillet of fried apples and potatoes, still warm. She fixed herself a plate and plopped down on the log nearest the fire.

Something’s coming.

She jerked and shoved the thought away, leaning closer to the fire. The sharp October wind cooled her back, while the fire toasted her face. At a sharp noise, her head shot up, but it was only Belle, gathering ash into a pail on the far side of the fire circle. The woman glanced at Winter, her face expressionless, before picking up the battered pail and heading back down the path that led to the wash hut at the creek’s edge, leaving her alone once again.

Winter gulped down the rest of her breakfast and stood. The heat from the fire had become almost uncomfortable. She took a step back and stared into the flames. Unease settled around her again. After washing her plate, she turned and wandered aimlessly toward one of the paths leading away from the circle. Briefly, she considered joining the other women at the creek but quickly dismissed that idea. Whenever she was around, they were tense, laughing awkwardly, shooting her looks from the side of their eyes.

And their scrutiny made her clumsy, inattentive. The clothes she was washing drifted downstream. The biscuits she was baking would refuse to rise. Once, while stirring lye for soap, she’d even managed to catch the hem of her shift on fire. No. She didn’t want to be around them any more than they wanted her around.

She found herself at the clearing, a flat open space filled with knee-high grass, turning from green to yellow in the deepening fall. Sinking down, she lay on her back and stared up at the sky. Clouds moved overhead and the sun disappeared behind them for a moment, taking the illusion of heat with them. Winter shivered. This was considered the boundary to Remembrance and almost no one came out this far. But she knew this was an illusion, knew that you could walk for days and days and never leave Remembrance, never see a soul who had not been allowed in, never be Outside. Only when Mother Abigail willed it, only when she dropped the Edge, would they become one with the rest of the world.

Winter had asked Mother Abigail to explain it to her once, how it was possible, and the old priestess had laid a faded handkerchief on her lap.

“See,” she said, smoothing it flat, “this is the world for everybody else.”

Then carefully, she had folded it, pleating it so that it had folded on itself like an accordion.

“But this how the world really is.” She ran a wrinkled finger inside one of the pleats. “I just bent space a tiny bit and made us this place here. Inside a’ one a’ these folds.”

“World there. And another world. And another yet.” She stroked the parallel folds. “Us? We here. And folks only see what they expectin’ to see. So they don’t really see.”

“But how, Mother Abigail?” she’d asked. “How do you fold up space like that?”

The old woman frowned and then she laughed. “How does that ol’man Willie wiggle his ears? Just something I can do.”

But there was more to it than that. Even as a little girl Winter had known that. She lay in the grass, watching the clouds slowly move across the sky. The cold seeped through her cloak and then her cotton shift, but still she lay there. A flock of geese cut across the sky, their discordant honking drifting down to her.

Mother Abigail would surely be looking for her, but for now she felt calm and at peace.

The grass rustled in the wind. And something else. She felt it. A slight crackling on her skin: sharp, unpleasant. She sat up. A dozen yards away, the clearing disappeared in a line of thick trees. A tall mulberry, its branches already bare after the first frost, marked the beginning of the forest. She was alone, and yet . . .

Something had changed, she could feel it. The skin on the back of her neck, between her shoulder blades, felt hot, as if she were standing directly in front of the Central Fire once again. The ground beneath her feet seemed to sag, as if some great weight were settling there beside her. There was no one in the clearing with her that she could see, but all her senses sounded an alarm. Something was wrong. She didn’t know what, but she knew she needed to leave. She needed to get back to the settlement. She stood just as the mulberry began to shake violently. A man burst from the forest into the clearing, and Winter cried out, stumbling backward. He fell once, then fell again. Rising to one knee, he stared at her, his eyes wild, terrified.

“Help me!” he croaked.

She stood, frozen, horrified, and then Mother Abigail was there. And Josiah, her constant companion, as always, never far behind. They went to the man, the priestess wrapping one strong arm around his waist lest he fall again. Together, Josiah and Mother Abigail half dragged, half carried the man back across the grass to where Winter still stood, too shocked to move.

The man looked to be in his early twenties, five or six years older than she was. He had skin the color of a hickory nut, and curly black hair that hung past his shoulders. His bottom lip was swollen and there was blood caked near his left temple.

Winter understood immediately that he was a runaway. But how was that possible? No one just appeared in Remembrance. Mother Abigail had to lower the Edge, to flatten out the folds that separated the spaces between worlds. She was about to ask, when she felt the clearing shift again, felt the painful crackling down her back. Her hair stood on end, sparking with energy, and she knew without touching it that it would be hot to the touch.

“Hey there, Zeus.”

They all spun toward the voice. From the corner of her eye she saw Mother Abigail stagger and nearly drop the runaway, who moaned softly. She gawked as a white man emerged from the trees. Though she had never seen one before, either a white man or a slave tracker, she knew him instantly for what he was. And in spite of her fear, she was curious.

The man wasn’t in fact, white at all, but a sort of grayish pink. His black hair looked greasy and hung limply in his eyes. The tip of his thin nose was red and pockmarked. Except for the gun that he carried loosely in his arms, there was nothing scary about him, and yet, she sensed the runaway’s terror. And Mother Abigail’s tension.

“How you holdin’ up there, Zeus?” asked the white man. His tone was calm, friendly.

“Kinda poorly, Master Clay,” said the runaway through his swollen lips.

“Zeus, you got to come on with me now, you hear?” The rifle rested in the crook of the slaver’s arm, the barrel pointed toward the ground. “You got the Gilliams all in a lather, boy. And frankly, I think you rather hurt their feelin’s runnin’ off like that. Come on back with me now. I hear tell they hardly ever beat their niggers. You might even get away with just a good, stern talking to.”

He smiled, but his eyes were hard beneath the lank hair.

Mother Abigail shifted the weight of the slave against Josiah and took a step toward the slaver.

“Get yourself away from here, you white Satan,” she snapped. “You’ll not be takin’ anyone from here. Not for no beatin’, not for no talkin’ to. This man has his freedom on him now. He belongs only to his own self. You can take that back to the Gilliams.”

The white man stiffened and his mouth dropped open as he glanced at the other three Negroes in the clearing. He shifted his gun, and Winter could see the muscles working in his jaw. He turned his attention back to Mother Abigail, his pale eyes narrowed, flashing rage.

“Look, Auntie . . . ,” he began.

“I ain’t your auntie,” snarled the old woman. “My name is Mother Abigail. You’ll need to be rememberin’ that.”

Clay shook his head and brought the barrel of the gun up slightly. “Ma’am—” He stopped short.

The air around them had begun to warm, and from the corner of her eye Winter could see the far end of the clearing warp slightly, lose its shape. She looked from Mother Abigail to the white man and back again. The slaver could feel the shifting around them, too. She could see it in his eyes. He didn’t know what it was yet, but if he didn’t leave soon, he would. And it would be bad for him.

“Ma’am,” Clay began again, “ain’t got no truck with y’all. I just come for Zeus. He ain’t got no right to steal hisself, and I been paid to bring him back.”

He glanced at Winter and she saw him hesitate. She saw something else as well, the dawning of fear, the look of a man beginning to realize that he doesn’t know quite what he’s walked into.

It was hot in the clearing now and Winter was sweating under her wool cloak. A searing wind had begun to blow across the yellowed grass, bending the blades. The runaway had recovered himself a bit and looked around in confusion. The slaver cleared his throat, a soft sound that Winter seemed to hear more in her brain than in her ears.

“Zeus, you come along peaceful,” he said, his voice just the tiniest bit higher than before. “You know the law says I can drag your friends along, too, if they cause a ruckus, but they really ain’t none a’ my business.”

Zeus took a hesitant step forward, but Josiah seized hold of his tattered shirt, holding him back. The slaver grunted his displeasure, and the thin veneer of civility evaporated.

“Enough of this now,” he snapped, and moved to reach for Zeus, but Mother Abigail stepped in front of him, blocking his way.

“Heed me,” said the priestess. “You can leave this place a whole man or broken, but you will leave.”

Winter bit her lip. Go. Just go, she silently pleaded. Go now, before it’s too late. The priestess could bring up the Edge if she wanted, there was no reason to keep talking to this slaver man. He had to realize that he was no real threat to them. He had to feel that. Maybe Mother Abigail would just let him go.

But she wouldn’t. Not now. Rage had hold of her. Winter felt it, they could all feel it, pulsing off the priestess in waves as Mother Abigail’s fury, her hatred of this slave catcher, twisted and warped, transforming from emotion into pure energy. If the slaver didn’t run, run now, then the Gilliams and Zeus would be the last thing on his mind.

The heat in the clearing had become nearly unbearable. Sweat rolled between Winter’s shoulder blades, pasting her cloak against her back. The air stung her throat, her nose. The slaver’s eyes swung between Mother Abigail and Josiah, then back again, sweat beading on his lip. He took a step back and Winter saw him raise his gun.

Beside her, Zeus was trembling, and Winter grabbed his hand before he could bolt. She could sense his heart racing and held on tight.

When Mother Abigail’s powers were unleashed like this, it was best to stand very still. It was better to be nowhere near her, but there was no hope for that now. All they could do was hold still and hold on. Overhead came a crash, like thunder. The sky had turned flat and gray as a dinner plate. Hot, superheated air whipped the gentle wind into a swirling gale. It lashed the high grass, and a cloud of Ohio dirt rose up and engulfed the slaver in a tornado of rich black soil, scouring his skin. He cried out, dropping his gun as he fell back. For a moment he seemed to disappear and the world spun around them. Winter gritted her teeth, fought for balance.

The slaver was there, farther into the trees, then gone. For a split second she saw him again, standing in a bright clearing, the winds calm, the sun shining. His mouth was open in a silent scream and he seemed not to see them from where he stood, trapped in the folds of time and space. Lost.

Mother Abigail raised her hands.

“No, Abigail!” cried Josiah. He lunged for the priestess and there was another clap of thunder. The ground pitched, throwing them all to the ground.

And then . . . silence.

Mother Abigail whirled toward Josiah, eyes blazing.

“You let him make you lose the thread like that, Abigail?” he asked, calmly returning her gaze. “You one of one. He just one of many.”

The old woman was breathing hard. Winter got slowly to her knees. It was cooling off again. The wind a normal wind now. She tasted grit in her mouth. She glanced at the slaver. He sat, legs akimbo, in the dirt. His face was bloodied and scraped, his dark hair gray now, coated with dirt. He stared at them, unseeing.

“One less,” said Mother Abigail, her voice hard, staring with disgust at the white man at her feet. “Don’t need to kill him. Just need to lose him. Remembrance not the only world I know how to make.”

She laughed grimly, and the sound made the hairs stand up on the back of Winter’s neck. Josiah pulled his pipe from his shirt pocket.

“You lose him, another one just take his place,” he said, tapping tobacco into his palm.

Mother Abigail said nothing for a long moment, then she grunted and bent over the prostrate slaver. Winter tensed.

But the old priestess peered into Clay’s blank face. “Ou se kaka, blanc,” she whispered. “Remember this place and never come here again. Remember my name.”

The slaver flinched and tried to scrabble away. Mother Abigail straightened.

“Get the boy,” said Mother Abigail, pointing at Zeus, who still lay trembling on the ground.

She raised her arms, seemed to falter for a moment, then suddenly the air was fresh and cool. The slaver was gone, as if he had never existed. Once again, Winter felt the familiar hum against her skin. The Edge had been restored. They were back in Remembrance: safe, separate.

Without a word, Mother Abigail turned to follow the trail that would lead them to the center of the settlement, as Josiah helped Zeus to his feet. Winter, her heart still beating wildly, turned to follow. At the trailhead she turned to look back at the clearing. From somewhere deep in her head, she thought she heard the slaver scream.

Copyright © 2020 by Rita Woods

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window