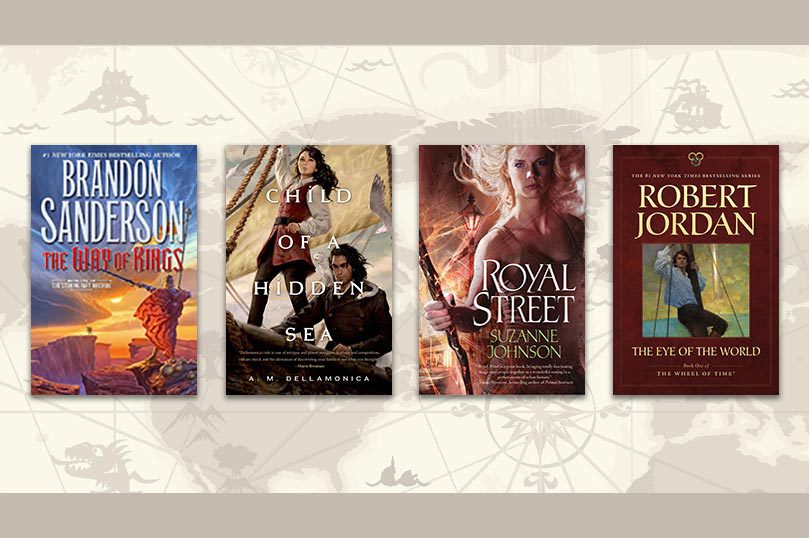

Fantasy Firsts Sweepstakes

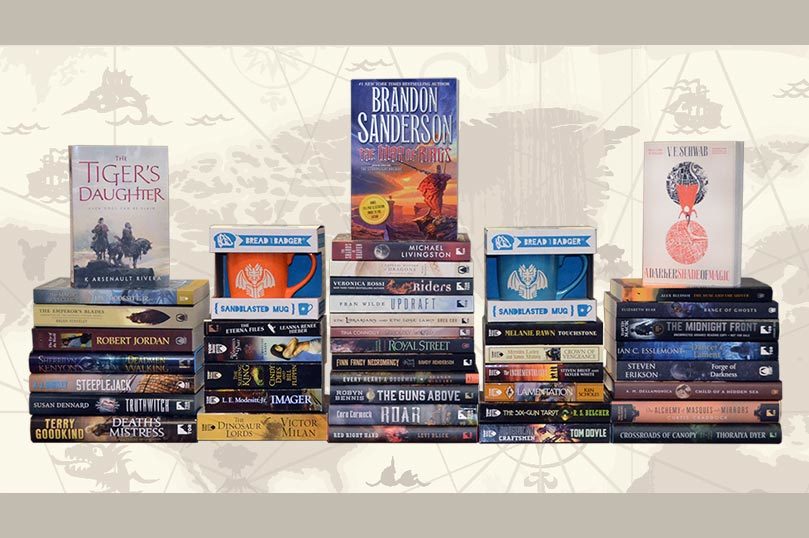

It’s November, which means we are entering the last month of our Fantasy Firsts program. We wanted to say thank you with a special sweepstakes, featuring ALL the titles we highlighted this past year. That’s 40 fantastic reads from 40 different series to add to your TBR stack! Plus, we’re including an added bonus: two sandblasted book dragon mugs, so you can enjoy your coffee or tea in style while you read.