New Series from Seasoned Fantasy Authors Coming in 2022!

Check out this list to see some upcoming new series from seasoned authors that deserve a space at the top of your TBR.

Check out this list to see some upcoming new series from seasoned authors that deserve a space at the top of your TBR.

Nothing heralds in the fall season better than seeing Halloween candy displayed front and center in stores. This spooky holiday season, trick or treat yourself to a good book and matching candy. Take a bite out of entries in beloved franchises, thrilling conclusions to series or start a new series, because nothing screams scary season more than candy, thrills, and a good book.

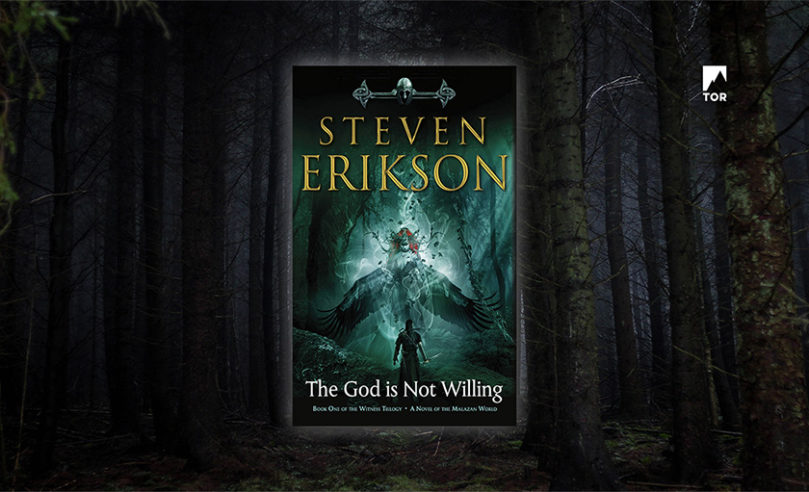

Please enjoy this free excerpt of The God is Not Willing by Steven Erikson, on sale 11/09/2021.

What is that in the air? Freshly fallen leaves? The smell of pumpkin spice? Oh wait, it’s the sound of brand new books dropping! Check out every book coming from Tor Books this fall here.