Writing Out of Order

Author Susan Dennard describes how she learned that writing chronologically isn’t always the answer, and you don’t need to begin at the beginning.

Author Susan Dennard describes how she learned that writing chronologically isn’t always the answer, and you don’t need to begin at the beginning.

Gruesome rituals, a mysterious death, and a town full of secrets…what fun! We were delighted to get a chance to chat with Kim Liggett, author of The Last Harvest.

Author Gregg Hurwitz explains how Halloween and things that go bump in the night prepared him for his writing career.

Vassa in the Night author Sarah Porter creeps us out by explaining how changelings worked.

Vicarious author Paula Stokes talks about writing what you feel.

The Glass Arrow author Kristen Simmons talks about the state of dystopia.

Carrie Jones tells you why you would want a cheerleader to be there to fight aliens with you. Push aside the cheerleader stereotypes and enjoy!

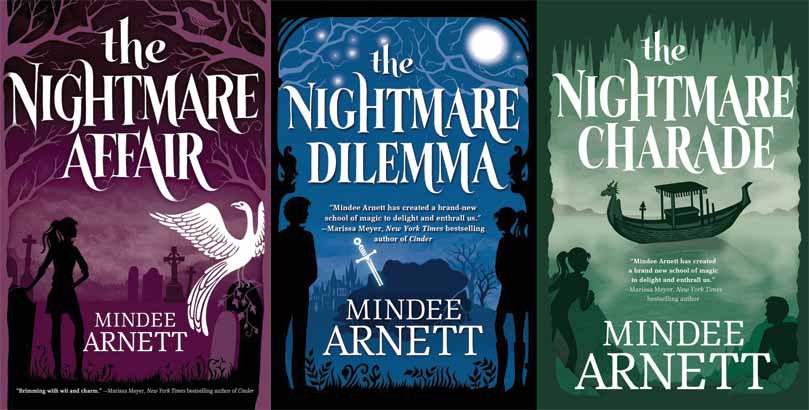

Author Mindee Arnett talks about building her Arkwell Academy series.

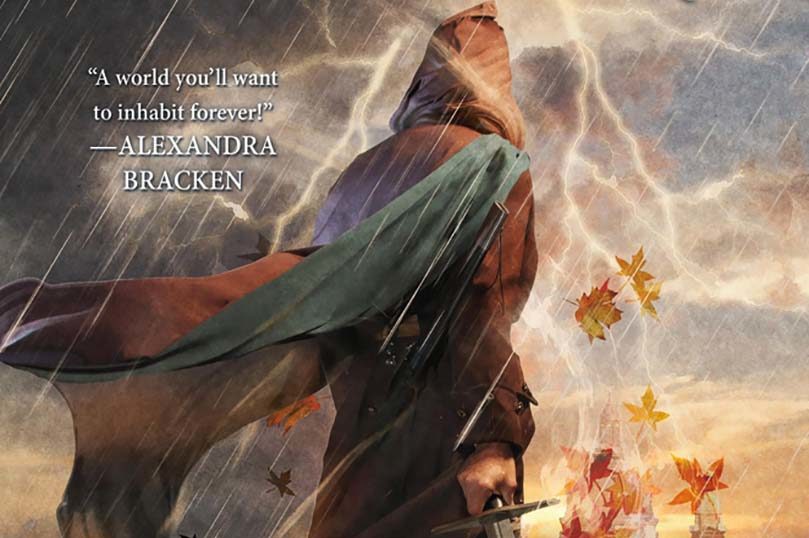

Steeplejack author A.J. Harltey talks about “the Jurassic Park conundrum,” writing people of color while white, and more in the Tor Newsletter.

A guest post from Exile for Dreamers author Kathleen Baldwin.