Tor’s Whimsically Energizing Spring Quiz

Can you hear the sound of many birds calling? Their song heralds the arrival of Spring.

Can you hear the sound of many birds calling? Their song heralds the arrival of Spring.

We’ve got something to put a spring in your step this season! Check out this rundown of every new title from Tor over the next few months!

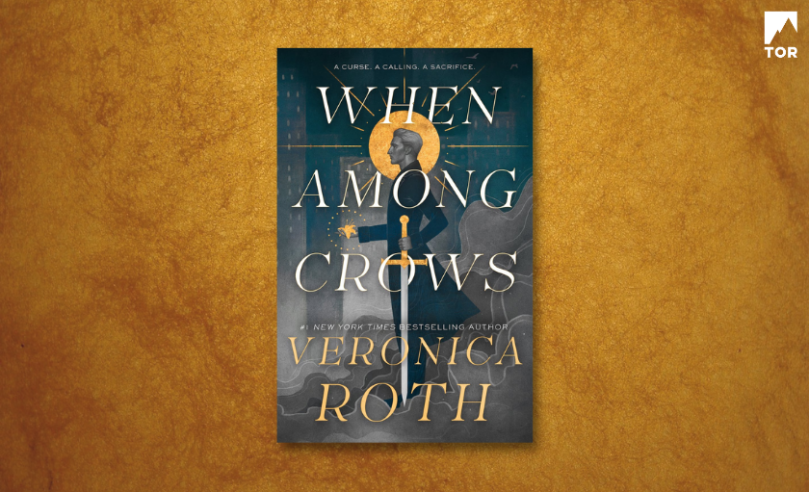

Please enjoy this free excerpt of When Among Crows by Veronica Roth, on sale 5/14/24

We’ve got the comfortable amenities and coldness of modernity mingling with the evocative mystique of legend, right here!