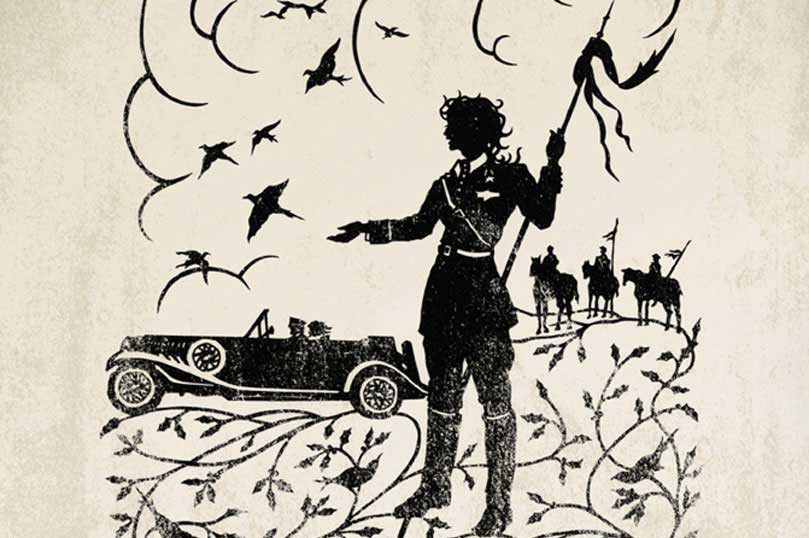

Fairy tales have always been about getting through the worst of everything, the darkest and the deepest and the bloodiest of events. They are about surviving, and what you look like when you emerge from the trial. The reason we keep telling fairy tales over and over, that we need to keep telling them, is that the trials change. So the stories change too, and the heroines and villains and magical objects, to keep them true. Fairy tales are the closets where the world keeps its skeletons.

Deathless is that kind of fairy tale.

In Russian fairy tales, the narrative flows a little differently. In those stories, you won’t find a tale for Cinderella, one for Snow White, one for Rapunzel. Instead, a peculiar cast of characters recurs over and over, in nearly every story, performing different acts and suffering different sorrows, but remaining the same. Ivan the Fool. Yelena the Bright. Baba Yaga. Vasilisa the Brave. Koschei the Deathless.

Ivan is always the youngest of three sons. Baba Yaga sometimes helps and sometimes harms, but her house on chicken legs always makes a grand entrance. Koschei always hides his death in the eye of a needle, inside an egg, inside a chicken, inside a cat, inside a hound, inside a horse, and so on. Like a soap opera, these characters play out a hundred different dramas. Some of them are known in the West—for instance, Baba Yaga made the transition to popular mythology. Some, like Koschei, are almost completely unknown—though I note with a little smile how infatuated our culture seems to be with a certain twilit archetype, the kind of man who steals young girls away, who drinks blood but can still come out in the daylight, deathless and dangerous but still oh so seduced by human women.

And then there’s Marya Morevna, who appears just once, in one grand story, and no more. She is a warrior, the queen from beyond the sea, not just beautiful or clever like the princesses of the other tales, but a queen, with terrible power–power enough to keep Koschei the Deathless chained up in her basement for the always-unfortunate Ivan to find. The sly tale offers no explanation for the contents of Marya’s cellar. She opens the story by killing a vast field of soldiers, and the reason for that is also left mysterious. She is a female Bluebeard, with a moral standing somewhere between Snow White and Snow White’s stepmother.

Deathless is her book.

This is a story that lives in the gaps of the original–why does Marya Morevna kill, what does she want, how did the very devil come to be chained against her basement wall? Alongside these answers lies the long dark fairy tale of the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the siege of Leningrad. Magic and politics have been bedfellows for a long time, you see. Once, it was the only way to write about oppression without incurring official wrath. Stalin didn’t do that terrible thing–Baba Yaga did. It’s just a story, you know. Russia has a long tradition of tucking true stories of blood and pain into fairy tales, closing them away for safekeeping in the eye of a needle, in the center of an egg. Though I will not suffer for the tales I tell as some brave authors did, Deathless is part of that tradition, and I have tried to give it all the respect and love I have.

The trials change.

The tale stays the same.

Deathless (978-0-7653-2630-0 / $24.99) by Catherynne M. Valente became available from Tor Books in March.

…………………………

From the Tor/Forge April newsletter. Sign up to receive our newsletter via email.