Written by Ilana C. Myer

Recently at Bookcon I participated in a panel about villains in science fiction and fantasy, and it got me thinking. I have some pretty strong ideas about villains in fiction, which panel moderator Charlie Jane Anders’ incisive questions forced me to re-examine. And having these ideas clarified in one’s mind is invaluable for a writer’s toolbox.

I thought about how dissatisfied I often am with commentary on Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. One of the most common criticisms of Tolkien is that his characterization is “Manichean” (the critics’ word, not mine)—the good guys are very good, the bad guys very bad, and there’s no nuance. I’m done wondering if we read the same book. I’ll just lay out what I think, in the context of what it means to create an effective villain.

It’s true Sauron is not a multi-dimensional villain (despite Elrond’s assertion that he was once good, that “nothing is evil in the beginning”). If you want a complex villain in Tolkien you have to look to Gollum, Saruman, or even Denethor. A villain like Sauron is more of a dark force than a character. He has a different narrative purpose—to galvanize the protagonists, though not just to action. Sauron forces the heroes of Lord of the Rings onto the battleground of the psyche.

Through the Ring—an extension of Sauron—the protagonists contend with their own temptations, weaknesses, and most denied impulses. We see this most clearly in Gollum, who is corrupted by the Ring and presented as a mirror image of Frodo—the person Frodo is in danger of becoming. But we see it with other characters, too, such as Galadriel, whose secret desire for power is laid bare by the Ring. Far from consisting of bland, benign, cloyingly nice good guys, Lord of the Rings depicts characters struggling with what is most alluringly dark within themselves. Each character’s internal battle is unique, depending on the temptation that lies nearest his or her heart.

In my view, a good epic fantasy will usually have more than one kind of villain, or flawed hero. In George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire we have outright monsters like Gregor Clegane and Joffrey Baratheon, but also Jaime Lannister whom you might actually want to have a beer with. And then there are the White Walkers, unambiguously evil, the threat everyone will be forced to stand against. The complexity introduced by a variety of antagonists enriches the story.

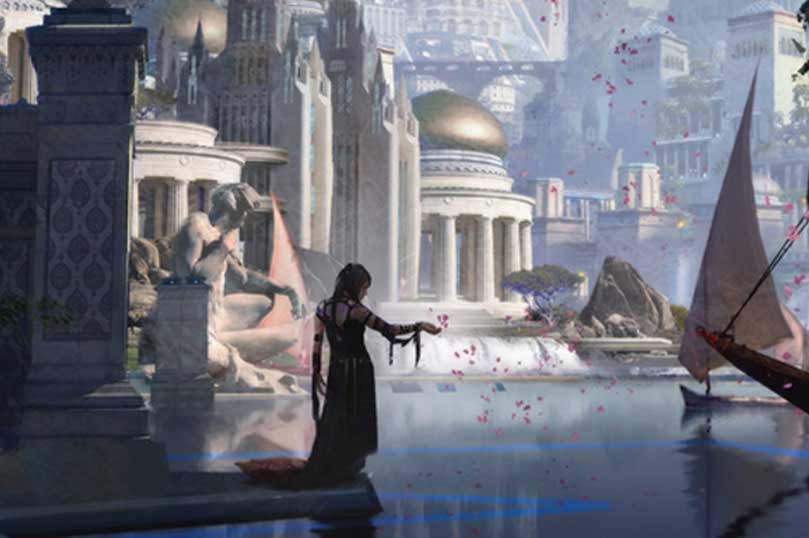

My debut novel about poetry and enchantments, Last Song Before Night, is layered around several antagonists. One of these is a Court Poet who becomes twisted by dark magic. Others act from impulses painfully human, or as a result of irreparable hurt. Along the way they hold a dark mirror to the protagonists, revealing who they might become as a consequence of even one misstep—a wrong turn in the road.

The humanizing of an antagonist hinges on what they want—what we desire is where we are most vulnerable. A sympathetic antagonist challenges the reader, makes the reader conflicted about the outcome of the story. I’m of the mind that a conflicted reader is generally a good thing. So perhaps the compassionate author, who secretly loves all the characters, even the bad ones, is in truth the cruelest villain of all.

Buy Last Song Before Night today:

Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Books-a-Million | iBooks | Indiebound | Powell’s

Follow Ilana C. Myer on Twitter at @IlanaCT and on her website.

Ilana, that is an amazingly gorgeous cover! And then I read about court poets and corrupting dark magic? Sounds great!!!

No, I don’t want to have a beer with Jaime Lannister. But I would pay for his therapy, if I had the $. And as a teenage girl, I might have had a crush on him.

Good essay, thanks.

You’re right about sympathetic antagonists — but I think you’re trying too hard to re-set Tolkien. Heroes can have weaknesses instead of being cardboard superpeople; Tolkien shows this well. (But he’s not the only writer of that time who does; see, e.g., _The Blue Star_.) But do you see any dark-side character in Tolkien that you’d want to have a beer with, or even have the slightest sympathy for? I don’t think we’re supposed to have sympathy even for Saruman — he’s everything that Tolkien (in his deluded pastoralism) opposed; Denethor could be charged with the sin of despair in some theologies, but I wouldn’t consider him a villain. (Tolkien’s work was shadowed by World War I; he would have had many models of parents undone by the death of a son.)

I hear you, but I actually have a lot of sympathy for Gollum, much as I wouldn’t want to hang out with him! And I think there is a tragic grandeur to the downfall of Saruman.

In general, Tolkien’s are not the kind of characters you go to a bar with–except the hobbits, of course.