Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from the first book in the Golgotha series. The Six-Gun Tarot by R.S. Belcher dives into a weird Wild West world where Buffy the Vampire Slayer meets Deadwood. The next book in the series, The Queen of Swords, will be available on June 27th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from the first book in the Golgotha series. The Six-Gun Tarot by R.S. Belcher dives into a weird Wild West world where Buffy the Vampire Slayer meets Deadwood. The next book in the series, The Queen of Swords, will be available on June 27th.

Nevada, 1869: Beyond the pitiless 40-Mile Desert lies Golgotha, a cattle town that hides more than its share of unnatural secrets. The sheriff bears the mark of the noose around his neck; some say he is a dead man whose time has not yet come. His half-human deputy is kin to coyotes. The mayor guards a hoard of mythical treasures. A banker’s wife belongs to a secret order of assassins. And a shady saloon owner, whose fingers are in everyone’s business, may know more about the town’s true origins than he’s letting on.

A haven for the blessed and the damned, Golgotha has known many strange events, but nothing like the primordial darkness stirring in the abandoned silver mine overlooking the town. Bleeding midnight, an ancient evil is spilling into the world, and unless the sheriff and his posse can saddle up in time, Golgotha will have seen its last dawn…and so will all of Creation.

The Page of Wands

The Nevada sun bit into Jim Negrey like a rattlesnake. It was noon. He shuffled forward, fighting gravity and exhaustion, his will keeping him upright and moving. His mouth was full of the rusty taste of old fear; his stomach had given up complaining about the absence of food days ago. His hands wrapped around the leather reins, using them to lead Promise ever forward. They were a lifeline, helping him to keep standing, keep walking.

Promise was in bad shape. A hard tumble down one of the dunes in the 40-Mile Desert was forcing her to keep weight off her left hind leg. She was staggering along as best she could, just like Jim. He hadn’t ridden her since the fall yesterday, but he knew that if he didn’t try to get up on her and get moving, they were both as good as buzzard food soon. At their present pace, they still had a good three or four days of traveling through this wasteland before they would reach Virginia City and the mythical job with the railroad.

Right now, he didn’t care that he had no money in his pockets. He didn’t care that he only had a few tepid swallows of water left in his canteen or that if he managed to make it to Virginia City he might be recognized from a wanted poster and sent back to Albright for a proper hanging. Right now, all he was worried about was saving his horse, the brown mustang that had been his companion since he was a child.

Promise snorted dust out of her dark nostrils. She shook her head and slowed.

“Come on, girl,” he croaked through a throat that felt like it was filled with broken shale. “Just a little ways longer. Come on.”

The mare reluctantly heeded Jim’s insistent tugging on the reins and lurched forward again. Jim rubbed her neck.

“Good girl, Promise. Good girl.”

The horse’s eyes were wide with crazy fear, but she listened to Jim’s voice and trusted in it.

“I’ll get us out of here, girl. I swear I will.” But he knew that was a lie. He was as frightened as Promise. He was fifteen years old and he was going to die out here, thousands of miles from his home and family.

They continued on, heading west, always west. Jim knew far ahead of them lay the Carson River, but it might as well be on the moon. They were following the ruts of old wagon train paths, years old. If they had more water and some shelter, they might make it, but they didn’t. The brackish salt ponds they passed spoke to the infernal nature of this place. For days now, they had stumbled over the bleached bones of horses, and worse. Other lost souls, consigned to the waste of the 40-Mile.

During the seemingly endless walk, Jim had found artifacts, partially eaten by the sand and clay—the cracked porcelain face of a little girl’s doll. It made him think of Lottie. She’d be seven now. A broken pocket watch held a sun-faded photograph of a stern-looking man dressed in a Union uniform. It reminded him of Pa. Jim wondered if some unfortunate wandering this path in the future would find a token of his and Promise’s passing, the only record of his exodus through this godforsaken land, the only proof that he had ever existed at all.

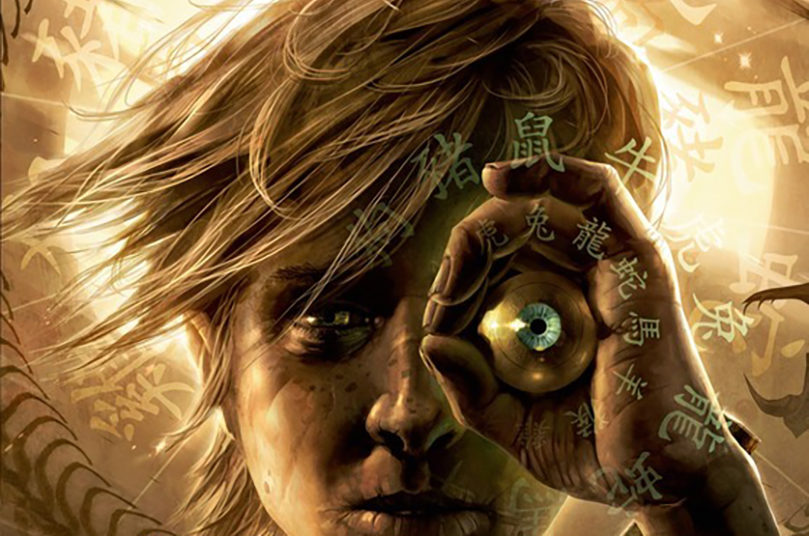

He fished the eye out of his trouser pocket and examined it in the unforgiving sunlight. It was a perfect orb of milky glass. Inlaid in the orb was a dark circle and, within it, a perfect ring of frosted jade. At the center of the jade ring was an oval of night. When the light struck the jade at just the right angle, tiny unreadable characters could be seen engraved in the stone. It was his father’s eye, and it was the reason for the beginning and the end of his journey. He put it back in a handkerchief and stuffed it in his pocket, filled with an angry desire to deny it to the desert. He pressed onward and Promise reluctantly followed.

He had long ago lost track of concepts like time. Days were starting to bleed into one another as the buzzing in his head, like angry hornets, grew stronger and more insistent with each passing step. But he knew the sun was more before him now than behind him. He stopped again. When had he stopped to look at the eye? Minutes ago, years? The wagon trails, fossilized and twisting through the baked landscape, had brought him to a crossroads in the wasteland. Two rutted paths crossed near a pile of skulls. Most of the skulls belonged to cattle and coyotes, but the number that belonged to animals of the two-legged variety unnerved Jim. Atop the pile was a piece of slate, a child’s broken and discarded chalkboard, faded by sand, salt and sun. On it, in red paint, written in a crude, looping scrawl were the words: Golgotha: 18 mi. Redemption: 32 mi. Salvation: 50 mi.

During Jim’s few furtive days in Panacea, after crossing over from Utah, he had been surprised by the number of Mormons in Nevada and how much influence they had already accumulated in this young state. There were numerous small towns and outposts dotting the landscape with the most peculiar religious names, marking the Mormon emigration west. He had never heard of any of these towns, but if there were people there would be fresh water and shelter from the sun.

“See, Promise, only eighteen more miles to go and we’re home free, girl.” He pulled the reins, and they were off again. He didn’t much care for staying in a place named Golgotha, but he was more than willing to visit a spell.

The trail continued, the distance measured by the increasing ache in Jim’s dried-out muscles, the growing hum in his head that was obscuring thought. The sun was retreating behind distant, shadowy hills. The relief from the sun was a fleeting victory. Already a chill was settling over his red, swollen skin as the desert’s temperature began to plunge. Promise shivered too and snorted in discomfort. There was only so much farther she could go without rest. He knew it would be better to travel at night and take advantage of the reprieve from the sun, but he was simply too tired and too cold to go on, and he feared wandering off the wagon trail in the darkness and becoming lost.

He was looking for a place to hole up for the night when Promise suddenly gave a violent whinny and reared up on her hind legs. Jim, still holding the reins, felt himself jerked violently off the ground. Promise’s injured hind leg gave way and both boy and horse tumbled down a rocky shelf off to the left of the rutted path. There was confusion, and falling and then a sudden, brutal stop. Jim was prone with his back against Promise’s flank. After a few feeble attempts to rise, the horse whimpered and stopped trying.

Jim stood, beating the dust off his clothes. Other than a wicked burn on his wrist where the leather reins had torn away the skin, he was unharmed. The small gully they were in had walls of crumbling clay and was sparsely dotted with sickly sage plants. Jim knelt near Promise’s head and stroked the shaking mare.

“It’s okay, girl. We both need a rest. You just close your eyes, now. I’ve got you. You’re safe with me.”

A coyote howled in the distance, and his brethren picked up the cry. The sky was darkening from indigo to black. Jim fumbled in his saddlebags and removed Pa’s pistol, the one he had used in the war. He checked the cylinder of the .44 Colt and snapped the breech closed, satisfied that it was ready to fire.

“Don’t worry, girl; ain’t nobody gitting you tonight. I promised you I’d get us out of here, and I’m going to keep my word. A man ain’t no good for nothing if he don’t keep his word.”

Jim slid the coarse army blanket and bedroll off the saddle. He draped the blanket over Promise as best he could, and wrapped himself in the thin bedding. The wind picked up a few feet above their heads, whistling and shrieking. A river of swirling dust flowed over them, carried by the terrible sound. When he had been a boy, Jim had been afraid of the wind moaning, like a restless haint, around the rafters where his bed was nestled. Even though he knew he was a man now and men didn’t cotton to such fears, this place made him feel small and alone.

After an hour, he checked Promise’s leg. It was bad, but not so bad yet that it couldn’t heal. He wished he had a warm stable and some oats and water to give her, a clean brush for her hide. He’d settle for the water, though. She was strong, her heart was strong, but it had been days since she had taken in water. Strength and heart only went so far in the desert. From her labored breathing, that wasn’t going to be enough to reach Golgotha.

The frost settled into his bones sometime in the endless night. Even fear and the cold weren’t enough to keep him anchored to this world. He slipped into the warm, narcotic arms of sleep.

His eyes snapped open. The coyote was less than three feet from his face. Its breath swirled, a mask of silver mist in the space between them. Its eyes were embers in a fireplace. There was intelligence behind the red eyes, worming itself into Jim’s innards. In his mind, he heard chanting, drums. He saw himself as a rabbit—weak, scared, prey.

Jim remembered the gun. His frozen fingers fumbled numbly for it on the ground.

The coyote narrowed its gaze and showed yellowed teeth. Some were crooked, snagged, but the canines were sharp and straight.

You think you can kill me with slow, spiritless lead, little rabbit? Its eyes spoke to Jim. I am the fire giver, the trickster spirit. I am faster than Old Man Rattler, quieter than the Moon Woman’s light. See, go on, see! Shoot me with your dead, empty gun.

Jim glanced down at the gun, slid his palm around the butt and brought it up quickly. The coyote was gone; only the fog of its breath remained. Jim heard the coyote yipping in the distance. It sounded like laughter at his expense.

His eyes drooped, and closed.

He awoke with a start. It was still dark, but dawn was a threat on the horizon. The gun was in his hand. He saw the coyote’s tracks and wondered again if perhaps he had already died out here and was now wandering Hell’s foyer, being taunted by demon dogs and cursed with eternal thirst as penance for the crimes he had committed back home.

Promise stirred, fitfully, made a few pitiful sounds and then was still. Jim rested his head on her side. Her heart still beat; her lungs struggled to draw air.

If he was in Hell, he deserved it, alone. He stroked her mane, and waited for the Devil to rise up, bloated and scarlet in the east. He dozed again.

He remembered how strong his father’s hands were, but how soft his voice was too. Pa seldom shouted ’less he had been drinking on account of the headaches.

It was a cold West Virginia spring. The frost still clung to the delicate, blooming blue sailors and the cemetery plants early in the morning, but, by noon, the sky was clear and bright and the blustery wind blowing through the mountains was more warm than chill.

Pa and Jim were mending some of Old Man Wimmer’s fences alongside their own property. Pa had done odd jobs for folk all over Preston County since he had come back from the war. He had even helped build onto the Cheat River Saloon over in Albright, the closest town to the Negrey homestead.

Lottie had brought a lunch pail over to them: corn muffins, a little butter and some apples as well as a bucket of fresh water. Lottie was five then, and her hair was the same straw color as Jim’s, only lighter, more golden in the sunlight. It fell almost to her waist, and Momma brushed it with her fine silver combs in the firelight at night before bedtime. The memory made Jim’s heart ache. It was what he thought of whenever he thought of home.

“Is it good, Daddy?” Lottie asked Pa. He was leaning against the fence post, eagerly finishing off his apple.

“M’hm.” He nodded. “Tell your ma, these doings are a powerful sight better than those sheet iron crackers and skillygallee old General Pope used to feed us, darling.”

Jim took a long, cool draw off the water ladle and looked at Pa, sitting there, laughing with Lottie. Jim thought he would never be able to be as tall or proud or heroic as Billy Negrey was to him. The day Pa had returned from the war, when President Lincoln said it was over and all the soldiers could go home, was the happiest day of Jim’s young life. Even though Pa came back thin, and Momma fussed over him to eat more, and even though he had the eye patch and the headaches that came with it, that only made him seem more mysterious, more powerful, to Jim.

Lottie watched her father’s face intently while he finished off the apple, nibbling all around the core

“Was it Gen’ral Pope that took away your eye?” she asked.

Pa laughed. “I reckon in a matter of speaking he did, my girl. Your old daddy didn’t duck fast enough, and he took a bullet right in the eye. Don’t complain, though. Other boys, they got it hundred times worse.”

“Pa, why does Mr. Campbell in town say you got a Chinaman’s eye?” Jim asked, with a sheepish smile.

“Now James Matherson Negrey, you know good and well why.” He looked from one eager face to the other and shook his head. “Don’t you two ever get tired of hearing this story?”

They both shook their heads, and Billy laughed again.

“Okay, okay. When I was serving with General Pope, my unit—the First Infantry out of West Virginia—we were in the middle of this big ol’ fight, y’see.—”

“Bull Run? Right, Pa?” Jim asked. He already knew the answer, and Billy knew he knew.

“Yessir,” Billy said. “Second scrap we had on the same piece of land. Anyways, old General Pope, he made some pretty bad calculations and—”

“How bad, Pa?” Lottie asked.

“Darling, we were getting catawamptiously chawed up.”

The children laughed, like they always did.

Billy continued. “So the call comes for us to fall back, and that was when I … when I got a Gardner right square in the eye. I was turning my head to see if old Luther Potts was falling back when it hit me. Turning my head probably saved my life.”

Billy rubbed the bridge of his nose with his thumb and forefinger.

“You all right, Pa?” Jim asked.

“Fine, Jim. Fetch me some water, will you? So, Lottie, where was I?”

“You got shot in the eye.”

“Right. So I don’t recall much specific after that. I was in a lot of pain. I heard … well, I could hear some of what was going on all around me.”

“Like what, Pa?” she asked.

“Never you mind. Anyways, someone grabbed me up, and dragged me for a spell, and finally I heard the sawbones telling someone to hold me still, and they did and I went to sleep for a long time. I dreamed about you and Jim and your mother. The stuff they give you to sleep makes you have funny dreams. I remember seeing someone all dressed up fancy in green silk, some kind of old man, but his hair was long like a woman’s, and he was jawing at me, but I couldn’t understand him.”

“When did you wake up, Pa?” Jim asked. Even though he knew the story by heart, he always tried to flesh it out with any new details that he could glean from the retelling.

“Few days later in a hospital tent. My head hurt bad and it was kind of hard to think or hear.” Billy paused and seemed to wince. Jim handed him the wooden ladle full of cool water. He gulped it down and blinked a few times with his good eye. “They told me we had fallen back and were on our way to Washington for garrison duty. General Pope was in a powerful lot of trouble too.

“They told me I had lost the eye, but was mighty lucky to be alive. I didn’t feel too lucky right that minute, but compared to all the lads who didn’t come home at all, I figure I did have an angel on my shoulder.”

“So tell us about the Chinaman, Pa!” Lottie practically squealed.

Billy winced but went on, with a forced smile. “Well, when my unit got to Washington, a bunch of us fellas who were pretty banged up, we all went to stay at a hospital. One night in the hospital, this strange little Johnny, all dressed up in his black pajamas, and his little hat, he came sneaking into the ward and he crept up beside my bed.”

“Were you scared, Pa?” Jim asked.

Billy shook his head. “Not really, Jim. That hospital was so strange. The medicine they gave us, called it morphine, it made you feel all flushed and crazy. I honestly didn’t think the Chinaman was real. He spoke to me and his voice was like a song, but soft, like I was the only one in the world who could hear him. He said, ‘You will do.’ I don’t to this day know what the blazes he was going on about, but he said something about the moon and me hiding or some-such. Then he touched me right here, on the forehead, and I fell asleep.

“Well, when I woke up I wasn’t in the hospital anymore; I was in some den of Chinamen. They were all mumbling something or other over top of me, and they were pulling these great big knitting needles outta my skin, but I didn’t feel any pain at all. The one who came into the hospital and fetched me, he said that they were healers and that they had come to give me a gift. He held up a mirror and I saw the eye for the first time. He told me it was an old keepsake from his kin back in China.”

“Did you believe him, Pa?” Jim asked.

Billy rubbed his temples and blinked at the afternoon sunlight again. “Well, I was a mite suspicious of him and his buddies, Jim. He told me the eye was real valuable, and that I should probably hide it under a patch, ’less crooks might try to steal it. That seemed a bit odd to me. He and the other Johnnies, they all chattered like parrots in that singsong talking those folks do. I couldn’t understand any of it, but they all seemed powerful interested in me and the eye. Then they thanked me and told me good luck. Another Chinaman blew smoke in my face from one of those long pipes of theirs, and I got sleepy and kind of dizzy and sick, like with the morphine. When I woke up, I was back in the hospital, and it was the next day. I told the doctors and my superior officer what happened, and they just seemed to chalk it up to the medicine they gave me. They had more trouble explaining the eye. The hospital was pretty crazy on account of all the hurt soldiers. They didn’t have much time to puzzle over my story—I was alive and was going to keep on living. They had to move on the next poor fella. Couple of them offered to buy the eye right out of my head, but it didn’t seem proper to give away such a fine gift. And it gave me a great story to tell my kids for the rest of my life.”

Billy grunted, and pulled himself to his feet. “A while later, the war was over and I got to come home. I never saw the Chinaman again. The end.”

“Let me see it, Pa!” Lottie said eagerly, practically humming with anticipation. “Please!”

Billy smiled and nodded. He lifted the plain black eye patch that covered his left socket. Lottie laughed and clapped. Jim crowded forward too to get a better glimpse of the seldom-seen artifact.

“It’s like you got a green-colored eye,” Lottie said softly. “It’s so pretty, Pa.”

“That green color in it, that’s jade,” Billy said. “Lots of jade in China.”

“Tea too,” Jim added.

Lottie stuck out her tongue at him. “You’re just trying to be all highfalutin and smart seeming,” she said.

“All right, you two, that’s enough,” Billy said, lowering the patch. “Let’s get back to work, Jim. Lottie, you run on home to your momma, y’hear?”

Jim watched Lottie dance through the tall, dry grass, empty pail in her small hand, the sun glistening off her golden curls. She was singing a made-up song about China and jade. She pronounced “jade” “jay.”

Jim glanced to his father, and he could tell that one of the headaches was coming on him hard. But he was smiling through it, watching Lottie too. He turned to regard his thirteen-year-old son with a look that made the sun shine inside the boy’s chest.

“Let’s get back to it, Son.”

He awoke, and it was the desert again. The green and the mountain breeze were gone. The sun was coiled in the east, ready to rise up into the air and strike. It was still cool, but not cold anymore. He remembered the coyote and spun around, gun in hand. Everything was still and unchanged in the gathering light.

Promise’s breathing was labored and soft. The sound of it scared Jim, bad. He tried to get her to rise, but the horse shuddered and refused to stir.

“Come on, girl, we got to get moving, ’fore that sun gets any higher.”

Promise tried to rise, coaxed by the sound of his voice. She failed. He looked at her on the ground, her dark eyes filled with pain, and fear, and then looked to the gun in his hand.

“I’m sorry I brought you out here, girl. I’m so sorry.”

He raised Pa’s pistol, cocked it and aimed it at the mare’s skull.

“I’m sorry.” His finger tightened on the trigger. His hands shook. They hadn’t done that when he shot Charlie. Charlie had deserved it; Promise didn’t.

He eased the hammer down and dropped the gun into the dust. He stood there for a long time. His shadow lengthened.

“We’re both getting out of here, girl,” he said, finally.

Jim rummaged through the saddlebags and removed his canteen. He took a final, all-too-brief, sip of the last of the water, and then poured the rest onto Promise’s mouth and over her swollen tongue. The horse eagerly struggled to take the water in. After a few moments, she rose to her feet, shakily.

Jim stroked her mane. “Good girl, good girl. We’ll make it together, or not at all. Come on.” They began to trudge, once again, toward Golgotha.

The Moon

The darkness filled with a terrible pressure behind his eyes. The pain was thick and settled over his skull like lead syrup. Jim opened his eyes and knives of sunlight stabbed into them. A groan escaped his cracked lips.

“It’s all right,” a voice said over the clatter of wagon wheels. “We got you, young fella. You’re going to be right as rain.”

Jim felt cool, spidery hands slide under his back and prop him up. He was under a wool horse blanket. It was scratchy against his red skin, but its shade was keeping the blazing sun off his head. A pale, cadaverous hand held a canteen before his mouth. There was a sour odor coming off the hand and for a moment he thought he was being ministered to by one of the dead pilgrims lost to the 40-Mile.

“Drink,” the voice said, and he did, in greedy, silvery, cold gulps.

“Not too fast,” a second voice said. “You’ll get sick.”

Jim’s vision was blurry and his eyes felt sticky. He turned his head enough to see the man who was holding the canteen. His face was thin; his sparse gray hair was swept back from his high forehead. His features reminded Jim of a vulture. He looked concerned for the boy’s condition, but he also seemed kind of fascinated by it too. Lottie had once looked at an ant she trapped under a Mason jar the same way.

“How is he?” the driver asked.

“Sick,” the vulture-man said. “He’s redder than a preacher in a whorehouse.”

“Promise,” Jim croaked. “My horse, is she okay?”

The cold hands turned Jim’s head toward the back of the wagon. Promise was shuffling behind the moving wagon, her reins looped around the stakes that ran along the sides of the wagon. She looked tired, but she was moving and she snorted when she saw Jim.

The boy managed a weak smile. “See, girl, I told you we would—”

He fell into buzzing darkness again.

It was a hot July evening. The lightning bugs were drifting across the front acre like sparks from a bonfire. Jim was sitting out on the porch of the homestead, trying to find Sagittarius in the night sky. Lottie was already asleep in the loft, but Jim was allowed to stay up later to play fiddle with Pa on the front porch. Momma would sing as the lightning bugs danced.

But tonight there wasn’t going to be any singing or playing. Jim could hear Ma and Pa fussing, inside the house, their voices gaining in speed and volume.

“Hush up now, William; the children will hear,” Momma said.

“Hell with ’em!” Pa bellowed. “Maybe they’d like to hear what a man’s gotta put up with just to have something to soothe his burning head.”

“You’re drunk,” she hissed. “Please, William, if it’s the headaches, we can go see Doc Winslow—”

“Doc Winslow can go straight to Hell, too!” Pa roared. “He ain’t got nothing in his little bag that’s gonna stop a Johnnyman’s curse. This damn eye … like ants made outta ice crawling in my skull.”

“Let me help you, darling, please.”

There were loud crashing sounds—pots and chairs knocked about, Momma crying out in terror. Pa threw open the door and staggered out into the warm, sticky night. He froze when he saw Jim standing there wide-eyed and silent.

“Pa,” Jim said. “Momma all right in there?”

Billy Negrey nodded slowly. Inside, Lottie was crying and Momma was calling out to her.

“Jim, you know I love your mother, don’t you?”

“Yes, sir,” Jim said.

“Sometimes this, this thing … in my head. I say things, I drink, ’cause it hurts so damn bad.”

“I know, Pa. Ma knows too. She knows.”

Billy staggered off the porch and toward the barn. He turned to regard his son. Billy’s skin was dream-spun silver in the bright moonlight. The eye patch was hidden in shadow. Jim was taken by how old he looked—not the years but the awful toll this life had exacted on him. His God-given eye fixed on Jim’s own.

“Take care of your mother and Lottie, Jim,” he said. “I’m going into town.”

A few minutes later he rode out of the barn on his horse and disappeared down the dirt road toward Albright. After a time, Lottie stopped crying. A little while after that, Jim heard the porch door close behind him and felt Momma’s small, strong hands rest on his shoulders.

“It’s all right, Jim,” she said softly. “Your poor father just needs to find himself some peace, that’s all.”

She wrapped her arms around him and began to sing “Barb’ra Allen,” her favorite song, low and sweet. It was old, like the mountains it came from, another place, another time. It was sad, but there was a beauty in the sadness that Jim didn’t fully understand but that soothed him nevertheless; it was Momma’s song. He picked up the fiddle and played it the way Pa had taught him.

The stars blazed and the lightning bugs drifted. The moon painted the world in smoky silver and endless ink. He felt her love, for him, for Pa, and all was right in the world then. It was all going to be just fine.

He never saw his father alive again.

Jim opened his eyes to a vast canopy of black velvet, sprinkled with silvery sand. He was on his back looking up. It was cold—a deep desert night. He struggled to sit up and blinked. He was under the warm horse blanket beside a crackling cook fire. About twenty yards to his left was the wagon he had been in earlier. To his right he could see Promise tethered to an emaciated excuse for a tree beside a pair of short paint horses. The mare seemed stronger, more alive than he had seen her since they had entered the arid hell of the 40-Mile Desert.

“She’s a good horse,” a man’s voice said from across the fire. “Strong heart, strong spirit.”

The man leaned closer toward the flames and Jim could make out his features in the frantic, shuddering firelight.

He was Indian, the first real one Jim had ever seen. His hair fell down to his shoulders in black, oily strands. His nose was crooked and seemed too thin and too pointy. His eyes reflected the firelight like spit on slate. His face was a grizzled topography of pockmarks and scars that made it hard to figure his age. His eyebrows grew together, colliding over the crook of his nose. He smirked when he saw the reaction his appearance created in the boy. The gesture revealed a mouthful of yellowed, snagged teeth and two very sharp, very straight incisors. The image triggered a memory in Jim that darted in his groggy brain, like fish in a pond, and then was gone.

“We’re keeping the horses over there so they can stay upwind of me,” the Indian said. “Horses don’t like me.”

“I thought horses liked Indians,” Jim muttered.

“Well, they don’t care much for me,” he said.

“Thank you,” Jim said, “for saving us. I’m obliged.”

The Indian shrugged and stood. He was short and thin, but there was a languid strength in him. Jim noticed the six-gun strapped to his left thigh and the huge hunting knife tied to his right.

“Mutt,” the Indian said, handing the boy a plate of cold beans and hunk of gray bread.

“Jim,” the boy managed to get out before his face dived into the plate. Mutt chuckled; it was a dry sound like sandstone underfoot.

“Figured you’d be hungry,” Mutt said. “How long you out there alone, Jim?”

“I kind of lost count. Days, I reckon. Promise, she got hurt on the … second day? That slowed us down a bit. We were trying to make it to Virginia City. I was looking for work.”

“On the railroad?”

“M’hm,” Jim murmured around a mouthful of beans and bread.

“Slow up there,” Mutt said, handing him a metal cup full of water. “Your belly’s ’bout the size of a hooter right now—you eat all that too quick, you’ll end up sicker’n a dog.”

Jim wiped his mouth on his sleeve and took a deep swallow of the water.

“How old are you, boy?’

“Turned fifteen, last October.”

“Where you from?”

Jim froze up a little. He tried to be as blasé as he normally was when it came to lying about his past, but it wasn’t easy when you were tired and sunburnt and groggy, and it seemed awful disrespectful to lie to the man who saved your life.

“Kansas,” he said after a beat.

Mutt looked at him for about the same amount of time, then nodded. “Kansas it is then. Well, you didn’t make it to Virginia City, but I’m sure you can scare up some work in Golgotha.”

“That where you from?”

The Indian nodded. “Presently.”

“I thought there was another fella with you,” Jim said. “I woke up and he was leaning over me, I think he gave me water.”

“Yup. That’s Clay. It’s his wagon.”

Mutt jerked his thumb in the direction of the buckboard.

“He’s asleep up in it. Afraid of waking up with the snakes.”

“Well, we sure were lucky you-all were passing through.”

Mutt frowned and refilled Jim’s cup from a canteen. “We weren’t exactly passing through, Jim. You’ve got some medicine about you.”

Jim laughed. It hurt, so he stopped as soon as he could. “Shoot, I ain’t no doctor. I’d feel sorry for anyone who I tried to fix up.”

“No, I’m talking about the old medicine, the first powers. The things that move like crazy smoke and fever dream through the worlds. White men call it magic—a little word to hide all the world’s truth behind. White men like to try to laugh at the things that scare the hell out of them. So, do you know any magic, Jim?”

Jim paused. He remembered what happened in the graveyard outside Albright—the unmarked grave and the eye. If he told anyone, even this crazy-sounding Indian, they would surely think he was insane. He shook his head and looked into the fire.

“No sir. I ain’t no wisdom, if that’s what you mean. I’m a God-fearing servant of Christ, and I don’t truck with no haints or boogeymen, or none of that, no sir. Devil’s business, it is.”

“Uh-huh,” Mutt said, but the yellowed grin was back. “Right. So why do you smell of power, power that I could track across the desert?”

“I … I don’t understand. You were out here looking for us?”

“I came across you out here the other night. I didn’t want to frighten you, so I went back to town and talked Clay into bringing his wagon out here to fetch you and Promise.”

Jim felt his memory grope around to fill in some detail, some impression that what Mutt was saying was solid. There was nothing. Had he been so tired he hadn’t seen or heard the Indian? Or was Mutt like the Indians in the dime novels he read, the ones with the orange covers and the stories of the wilderness? Those Indians were invisible, like smoke, or haints.

“I rightly don’t know,” Jim said, covering the pocket of his pants with his hand. “I ain’t got no power, Mutt. If I did, you think I’d be stuck out here?”

“Your folks know you out here?”

“Not much work back home,” Jim said, the lie sliding smoothly from his lips this time; he had plenty of practice telling this one and he had his footing about him again. “I told Ma and Pa I’d come out here and get a good-paying railroad job, send some money home.”

“Back to Kansas, right?”

“Yup.”

The cold air around them suddenly filled with howls and yips. Mutt stood again and his hand fell to his gun.

“Coyotes?” Jim said as he moved closer to the fire.

Mutt nodded. “They can see it too,” he said.

“What?”

There was movement in darkness, a swarm of dark motes hurtling forward across the plain toward the fire. Separating, accelerating. Hot breath, bloody eyes.

“Whatever that power is you don’t have,” he said as he pulled a burning branch out of the fire.

Jim rose, shakily, and grabbed a torch as well. He dug into his pant pocket frantically. “Is this it?” he said, and held up his father’s jade eye.

A snarling furry shape lunged out of the darkness toward Jim’s hand. Mutt was suddenly there; his firebrand smashed into the coyote’s flank with a whoosh and a wild shower of sparks. The animal yelped and crashed to the ground. It scampered to its feet and disappeared into the darkness. Another member of the pack snapped at Mutt’s vulnerable side, but Jim was there with his own torch. The animal howled in pain and retreated. The boy and the Indian stood back-to-back as the night encircled them and showed its sharp teeth.

“There’s got to be a dozen of them,” Jim said between ragged, frightened breaths.

Mutt grunted and brandished the torch. “Sorry to say, I’ve got a big family.”

“What?”

“They’re my kin.”

“Your kin?”

“My dad sent them,” Mutt said. “He loves shiny things. No chance you want to give that up, is there?”

“It was my pa’s,” Jim said. “I’m not giving it up to a bunch of smelly curs … no offense.”

“None taken. They’re the bad side of the family, and they really do smell.”

A gravel-edged growl called out from the darkness. A large, grizzled coyote padded into the circle of firelight. Its one good eye glared at the Indian.

“Squint,” Mutt said. “Didn’t know you were still prowling around doing Dad’s dirty work for him. Still haven’t learned you can’t suck up to the old man, eh?”

Squint snarled and froth exploded from his mouth. In the firelight’s trembling shadows Jim swore the animal looked like the Devil himself.

“Can’t do that, Squint,” Mutt said to the animal as he slid the knife free of its sheath. “It’s the boy’s birthright. Wouldn’t be proper to steal it. Besides, now that I know it’s you Dad sent out, I just want to mess with you.”

He grinned and showed the coyote his crooked teeth as he crouched close to the earth, ready to strike. Squint growled out a command to the others and they began to howl. The one-eyed coyote hunched, ready to pounce.

“What do think they’ll call you when you ain’t got no eyes left?” Mutt whispered.

The thunder of a shotgun blast rolled across the plain. One of the coyotes to the left of Squint was lifted up in the air, twisted in a cloud of bloody mist and fell, twitching, to the earth. The howling stopped.

Jim saw the vulture-man, the one Mutt had called Clay, standing in the back of the wagon, one of his shotgun’s barrels trailing silvery smoke up into the starlight. Clay’s hair was a ragged halo around his liver-spotted pate and he was wearing a pair of filthy long johns. It would have been comical if Jim hadn’t been so scared.

“Now, git!” Clay shouted. He leveled the shotgun at another of Squint’s pack and fired. The coyote’s whimper of pain was lost in the bellow of the blast. It fell as silent as its brother, unmoving on the ground. Clay frantically scrambled for more shells at his feet as he popped the still-smoking breech open.

Squint glared at Mutt, who met the gaze with hatred in kind. The big coyote sniffed, and then turned and ran, barking a long string of yips. The pack joined in as they, too, turned to flee. The desert grew quiet again except for an occasional howl.

“Well, don’t that beat the Dutch?” Clay said, hopping down off the wagon and hobbling, barefoot, toward the others. “Never seen coyotes act like that before. You, Mutt?”

The Indian shrugged. “Clay, this is Jim.”

“Jim Ne … Nelson, sir,” Jim said, pumping the old man’s hand when it was offered. “That was some good shooting up there.”

“Clay Turlough,” the old man replied. “Thank you, son. I’m a mite ornery when I get woke up ’fore I’m ready to.”

Clay looked out into the darkness. He seemed suddenly distracted. He handed Jim the open shotgun and then trotted into the shadows at the terminator of the fire’s light. He returned cradling one of the wounded, bloody coyotes in his arms.

“Well, Mutt, don’t seem the trip was a complete loss. This one’s not too torn up and look, he’s still huffing a little air. Let me get him over to the wagon and have a look-see.”

Jim looked at the Indian.

Mutt took the shotgun out of his hands and reloaded it. “Clay owns the only stable in Golgotha. He’s the closest thing we got to a horse doctor in these parts. Went to medical school for a few years. Didn’t work out too well from what I heard. He makes a decent living doing taxidermy for folks as far away as Carson City, though. He … collects … dead things.”

Jim approached the wagon while Mutt tended the fire. Clay had lit an oil lantern and set it next to the dying coyote on the back of the wagon. The old man had put on his boots and a trail coat over his long johns. His hands were black with blood, but he didn’t seem to mind. He was hunched near the animal’s face. Jim thought he heard him whispering to the animal, but Clay stopped when the boy approached.

“Ah, Mr. Nelson. Come see, young man; this is a unique educational opportunity for a lad of your age. See, see. He’s just at the threshold now.”

The animal’s eyes were wide. The pupils greedily drinking in every last flicker of light, scrapping for every final detail. Fear clouded the eyes like a cataract, but as the old man and boy watched the fear slid away from the eyes. A dumb peace settled over them, as if the animal was no longer looking at the same world any longer. Then the light flickered, and was gone. Clay audibly gasped.

“‘Man,’” he muttered, “‘how ignorant art thou in thy pride of wisdom.’”

Jim stared at him oddly.

“Shelley,” he said. It’s from Lady Shelley’s marvelous scientific fiction. We understand so little about life or its sister, death. Look at this animal. Why was it, a moment ago, alive and feeling and thinking and now it is changed, dead? Why?”

“’Cause you shot it,” Jim said.

Clay looked at him oddly, like he wasn’t standing in front of the old man or he hadn’t heard what Jim said. He blinked and the jovial old man was back, but the sour smell Jim had first caught off of him was there as well—a cross between formaldehyde and lilac water trying to hide it.

“You’ve had a busy day and a busier night, m’boy,” Clay said with a razor cut of a smile. He placed a bloody hand on the dead coyote’s flank.

“Get some rest.”

The two men took turns keeping watch. The coyotes didn’t return. Just before sunup, the men broke camp and doused the cook fire. They set off at dawn for Golgotha. Jim sat on the buckboard with Mutt while Promise trotted along behind the wagon. Clay and his dead coyote rode in the back.

As the day wore on, Mutt asked to see the eye. Jim reluctantly agreed. The Indian admired it, rolled it over in his callused, dirty hands. Jim noticed even his knuckles were hairy. Mutt tried to make out the tiny chains of inscriptions that ringed the iris.

“It’s Johnnyman talk, “Jim said. “Chinese, I reckon.”

“It’s not any kind of medicine I understand,” Mutt said finally. The two were talking softly. They need not be concerned, however; Clay was quite content to mutter to himself and the coyote. “Still, it’s powerful; I can feel it humming across the worlds.”

Jim nervously held out his hand, and after too long a pause Mutt dropped the eye back into the boy’s palm.

“You’d do well to not lose that,” Mutt said.

“It’s all I got left of my pa, and I don’t intend to ever part with it,” Jim said as he stuffed it back in his pocket.

They rode along in silence for hours. The desert was beginning to give way grudgingly to some greenery. Blackbrush, shadscale and an occasional yucca plant softened the unforgiving sameness of the plains. They began to spiral downward through small demi-canyons richer in low, hardy plants. Once, Jim felt a cool breeze off of some body of water caress his face for a moment. It was growing noticeably cooler as the greenery began to embrace them.

“So,” Jim finally said. “Your brother is a coyote?”

“Whereabouts in Kansas did you say your family was from … Mr. Nelson?” Mutt asked with a jagged smile.

Jim shut up.

A few miles later Mutt leaned forward on the seat and turned to look at the boy.

“Jim, I know you’re set on heading to Virginia City and that railroad job, but I’m here to tell you, I’ve traveled my whole life one step ahead of what was trying to bite me on the hindquarters. People with secrets, people running, need to keep to the shadows, out-of-the-way places where the world just passes on by.”

“Like Golgotha?” Jim said.

Mutt nodded. “Small towns, hell, just about everybody in ’em got some kind of secret. Everyone minds their own business, holds their peace. Place like Virginia City, you’d be stumbling over marshals and sheriffs, bounty hunters and Pinkerton men. All the latest wanted posters are up and everybody is nosy as hell, up in your business.”

“Why are you telling me all of this?” Jim said.

“Guess I like a man who keeps his horse alive in the desert, who grabs a torch and helps a fella out of a jam, even if the fella is half-breed Injun he don’t know from Adam.”

They passed a simple farmhouse with a corral pen full of placid cattle.

“You and Clay saved us,” Jim said. “Didn’t have to, didn’t need to, but you did anyway. My pa always said a man was what he did, not where he came from or what people thought about him. You did right by me and Promise.”

They passed old decrepit buildings made of dried mud set into the side of a mountain wall, a shrine of simple stones and a weathered Roman cross; the items seemed to be from vastly different times.

Mutt smiled and nodded. “Fair enough. More fair than most. Your secrets are safe with me, Jim Nelson from Kansas.”

They passed a cool stand of cottonwood trees on the left and a crumbling stone well on the right. The sky was bright and blue, shimmering with heat. The air smelled of sawdust and horse manure. The wagon slowed as they approached Main Street.

“Welcome to Golgotha,” Mutt said.

The Star

Golgotha opened her arms to him.

Jim had seen his fair share of towns in his travels toward the near-mythical railroad job in Virginia City. Golgotha seemed an odd mixture of old ruin and new paint, boom and bust—like an old lady all gussied up and powdered to meet her suitor, wearing too much makeup and gaudy schoolgirl ribbons in her hair, not caring about the incongruity of it, just happy to be alive and in love.

Golgotha was old, but she was still kicking.

They had passed the rotted wood skeletons of old dwellings and tattered tarp doorways to the cave homes—gouged into the cool blue rock of the mountain slumbering off to their left. It all whispered of age—lives long ago lived and put aside, memories that refused to be wholly eaten by the dust.

The first building that grabbed Jim was the theatre. It was a garish two-story affair off to his right, painted up in gray and mauve. The marquee stretched across the face of the building like a wide grin. It boldly proclaimed Professor Mephisto’s Playhouse and Showcase and further announced a production of Little Brown Jug currently ongoing.

Next door to the playhouse was Shultz’s General Store and Butcher Shop, according to a large sign in fat Slab Serif print. A heavyset man with a thick rust-colored handlebar mustache was sweeping up the wooden planks of the sidewalk in front of the store. He reminded Jim of the drawing of a walrus he had seen in a book once. The man wore a crisp, white apron, a fringe of red and smoke-colored hair encircling his sun-freckled pate and a warm smile he shared as the wagon passed.

“That’s Auggie,” Mutt said. “It’s his store. Well, it was his and Gert’s store. She passed a while back. Just about anything you need, Auggie’s got it, or can order it. Post office is in there too.”

The street was a wide moat of wet and dried mud, dust and manure. People made their way between the buildings, many sticking as close to the wooden sidewalks as their business would allow them. Others braved the street, trudging between the trotting horses, clattering wagons and the muck. Men tipped their hats to the ladies, interposing themselves between the dirty streets and the women. Most of the folk looked like regular people to Jim, but a few were dressed all fancy, like they were headed to church, even though it wasn’t Sunday.

Across the street from Shultz’s was the Paradise Falls Saloon, the largest building on the street. The Paradise had three stories, a wide covered porch on the ground level and a railed balcony wrapping around the second floor. Smaller balconies outside shuttered doors and parapets that were home to brooding angels or leering gargoyles adorned the third floor

A group of well-dressed men, awash in the smoke of their huge cigars, congregated in front of the Paradise. They guffawed over some unseemly joke and slapped each other on the back, nodding.

On the opposite side of the street from the Paradise Falls and next door to Auggie’s store resided the Golgotha Bank and Trust, a sturdy-looking building with iron bars over the windows.

Mutt couldn’t help but give a sly grin when he saw Jim’s expression as they passed the bank. The boy had caught sight of the Johnnies, headed up Main toward Auggie’s.

Jim gasped. Chinamen, real Chinamen. Not in a book or one of Pa’s stories of Washington. It was the first time in Jim’s life he had seen anyone so different in every way. They wore black tunics and loose pants, like pajamas, and wide cone-shaped straw hats that hid much of their faces in shadows. Sandals covered their feet and some were barefoot. He did a double take when he realized that some of them were women and were dressed the same as the men. No one tipped their hat to them, or shielded them from the street. They kept their heads down under their basket-hats. His hand slid into his pocket and cupped the jade eye.

“Chinese, mostly,” Mutt said. “A few from other places I can’t pronounce none too good. They’re out here looking for work on the railroads. Like you. Most of them live over in Johnny Town, off of North Bick Street. Got their own saloons, businesses, everything over there. I wouldn’t recommend wandering there alone, Jim.”

They passed a fancy-looking hotel, the Elysium, next to the saloon. Jim saw a barbershop that proudly advertised the dental services and curatives offered therein. Old men whittled on a bench next to the shop’s striped pole. An elderly Indian paused in his carving and nodded to Mutt. Mutt returned the gesture with the slightest of motions.

Across from the barber was the Corinthian-columned façade of Golgotha’s town hall.

Clay turned the wagon right onto a street named Prosperity. They passed a small cabin and a neatly whitewashed church on the opposite side of the road. The mountain was behind them now and when Jim looked back he saw that Prosperity Street snaked its way up the slope. There were tents, shacks and shanties, dozens of them farther up the mountain, a whole other small, ramshackle town, looking down on Golgotha.

“Argent Mountain,” Clay said as he noticed the boy’s gaze. “Ole Moneybags Bick’s hole in the ground. There were some good veins down in there. The silver brought people here from all over. Then it went bust a few years back.”

“Now you got lots of folks who live up there in the squatter camps, came here chasing a dream and ended up broke and lost in the desert,” Mutt said. “Figure Golgotha is as good a place as any to sit around and wait for your luck to change, or to die.”

“Hell,” Clay added, “damn sight better than some places.”

Ahead of them was another rise with a gentler slope. This hill boasted several homes residing on it of an obviously higher quality than the rest of the town, or the squalid shacks on Argent Mountain. Near the hill’s base was a beautiful building of dark wood and blued stone. Two steeples rose up out of its roof, both adorned with crosses. A literal wall of arched windows covered one side of the structure and reflected the brilliant sun in silvered mercury glass.

“What is that?” Jim asked.

“Rose Hill,” Clay said. “Where all the fancy folk live. Most of ’em is Mormons and that there is their temple.”

“That’s their church?” Jim leaned forward in the wagon, squinting against the light. “Looks like a king’s castle or palace or something.”

“They only use it for special ceremonies,” Mutt said. “They got a little meetinghouse off of Absalom Road they use most of the time. Not so off-puttin’.”

“I heard some strange stuff about them Mormons,” Jim said.

“They’re all right,” Mutt said blandly. “Bet you heard some strange stuff about Chinamen and Injuns too, huh?”

Jim said nothing. Mutt’s chuckle was a dry grunt.

Clay nodded toward a wide, rutted road off to the left, just past the whitewashed church.

Mutt brought the wagon to a halt. “This is where we get off, Jim,” he said. “Much obliged to you, Clay. Sorry about the horse.”

“Well, better luck next time,” the old man said with a shrug. He took the reins from the Indian. “Always glad to help out the law.”

Jim climbed down. He stroked Promise’s bony flank as he hefted the saddlebags awkwardly over his shoulders.

“See, girl, I told you we’d make it,” Jim whispered to the horse.

“Now don’t you fret, young fella,” Clay said with a wink. “I’ll stable her over at my place. It’s a long bit a week; you think you can afford that? You come by when you can even up. We square?”

“Uh, sure? Your place?”

“Straight down Pratt Road here,” Clay said, gesturing to the wide track. “Can’t miss it.”

“Thanks,” Jim said. “For everything.”

Clay smiled and shook the reins. The wagon clattered along with Promise following behind. They turned up the road and slowly disappeared into the curtain of heat and dust.

Mutt turned right onto a dirty little street just behind the cabin they had passed. The simple wooden sign announced it was called Dry Well Road. Jim hurried to catch up to the Indian. He noticed a lot of folks seemed to give Mutt a wide berth, moving to the other side of the narrow street and avoiding his unblinking gaze. Mutt didn’t seem to mind; if anything, Jim got the impression he enjoyed making the townsfolk feel uncomfortable.

“Why did you tell Clay ‘sorry’?” Jim said as they walked past a seedy boardinghouse and a livery and tack store.

“Huh?”

“‘Sorry,’” Jim repeated. “You told Clay ‘sorry’ and he said, ‘Better luck next time.’ Why?”

“Oh.” The Indian smiled, all yellow and jagged. “That. Well, the only way I could get him out there to the Forty-Mile was I told him your horse was pert near dead and if he would drive me out, he could have the carcass if she died.”

The blood ran out of Jim’s face. His tongue seized up. “Oh,” was all he could muster.

Mutt laughed again, shaking his head. “Now, Jim, he ain’t going to do nothin’ to Promise, ’cept feed her, brush her down and keep her safe. Clay is kind of odd about his little … hobby with dead things. But he won’t hurt her. She belongs to you, and he seems to have taken a shine to you.”

“Why is he such an odd stick about dying, though?”

“Everybody’s got something that puts wind in their lungs, Jim. Most folks it’s money or a fancy house. Some it’s another person. For Clay it’s figuring out how things tick and why they stop ticking.”

They continued down Dry Well. They passed a blacksmith’s shop. The rhythm of hammer and muscle against hot iron filled the space of their silence.

“Why did Clay say he was glad to help the law?” Jim asked finally.

Mutt buried his hand in the pocket of his dungarees. He pulled out a badge—a star of silver within a circle of the same. He showed it to Jim and then pinned it on his jacket lapel.

“You the sheriff here, Mutt?” Jim said, trying to keep the fear out of his voice. After the desert, it was easier.

The gaunt man laughed. “Hell, no! You’d have to be nine parts crazy to one part stupid to be sheriff in this town. Sounds like a job for a white man, you ask me. Nope, I’m just hired help.”

“Why did you take a job like that?”

“Got my reasons.”

They were approaching a squat cube of red brick. The bars on the windows and the heavy iron door, dented and scarred, a monument to old violence, told you what it was even before you read the sign hanging off the awning by two chains. A wooden board with public announcements was mounted next to the iron door. Wanted posters struggled in the stale, feeble wind to be free of the tacks pinning them to the board.

Jim’s stomach was full of black ice. “You taking me to jail now, Mutt?”

“Why would I be doing that?” he said. “Just checking in.”

He stepped onto the shade of the porch and tried the door. It was locked.

“Wonder where he’s got to?” Mutt said.

“Who?” Jim asked. He edged onto the porch, one step closer to the end of his life.

“The sheriff,” Mutt said. He fished out an iron key from his pocket and unlocked the door with a grunt and an audible clank. It swung inward on groaning hinges and cast bright sunlight into the inner darkness.

“Jon, you in there?” he called. No answer, just cool shadows. Mutt pulled the door shut and locked it.

“Must have had to head out for a spell,” he said. “His rifle and saddlebags are gone.”

“Deputy! Deputy!”

A man ran down the street from the opposite direction that Jim and Mutt had come. He was long legged and handsome, with a mane of hair, a handlebar mustache and muttonchops, all the color of rust. His eyes were as blue as the heart of a lit match. A brocade waistcoat of emerald and gold flashed under his jacket. He was red faced and sweating.

“What is it, Harry?” Mutt said.

The man paused and fished a handkerchief out of his pocket to mop his face. “It’s Earl Gibson. He’s making a ruckus fit to wake snakes. Busted into Auggie’s store, waving a gun around. Where the hell have you been?”

“Out,” Mutt said, reopening the jail’s door and disappearing inside. “I’m back now. Where’s Jon?”

“In Carson City, testifying at a trial,” Harry said. “He left a few days ago, after he got tired of waiting for you to decide to show back up, Deputy.” He then added, “Who the hell is the kid?”

Mutt reemerged from the darkness of the jail. He had a Winchester rifle in his hand. He looked at Jim and then crossed over to the public board. He ripped a wanted poster off the board, crumpled it into a wad and jammed it in his pocket.

“What the hell is that old thing still doing up there? Oh, him? He’s my sister’s boy: Jim. Jim, say hello to Harry Pratt. He thinks he’s a huckleberry above a persimmon.”

Pratt looked at Jim like he had the plague, then snapped his gaze back to Mutt. “I told Jon it was damn foolishness to put his faith in a drunken half-breed like you. You don’t have a sister; you don’t have anything, Mutt, including a job, once the town fathers hear how you’ve handled this situation.”

Mutt came off the porch toward Pratt. He cocked the Winchester’s lever and let it fall to his side. He seemed taller than the white man, even though he wasn’t. He stopped a few inches from Harry’s face.

“Let’s acknowledge the damn corn, Mr. Mayor,” Mutt growled. “I don’t work for you; I don’t work for the damn town fathers. I work for Jon and if you’ll excuse me I’ve got some work to do right now.”

He strode down the street in the direction Harry had appeared from.

Jim nodded to the red-faced mayor. “Uh, pleased to meet you, sir,” he stammered, and then sprinted off to catch up with the deputy. When he did, Mutt was turning the corner at Sprang’s Rooms for Rent, a rather questionable-looking boardinghouse, given the drunken and disheveled group of men gathered on its porch. Jim saw the crumbling stone well they had passed coming into town out past where the street ended. It seemed lonely, like a solitary, forgotten watchman welcoming newcomers to the town.

“What was that all about?” Jim asked when he finally caught his breath.

“That’s the mayor. Thinks his shi— Thinks he don’t make a mess when he goes to the outhouse. Just ’cause his family rolled out of the Forty-Mile twenty years ago and decided this was the Promised Land or some-such thinks he can do or say whatever he wants to whoever he wants. Pretty standard for white folk round these parts, really.”

“If you hate white people so much, why do you live with them?”

Mutt started to answer, then frowned.

“I may be killing a pretty decent fella in a few minutes, or getting a pretty decent fella killed. I don’t have time to babysit anymore. Get your ass back to the jail and wait for me, boy.”

“What if you get killed? And I ain’t no boy!” Jim said with heat blooming in his eyes.

Mutt grinned at the reaction. Mutt seemed to grin at most things that bothered other folk.

“Didn’t think about that. You better tag along. Can’t have you out on that porch like a stray. But I mean it, Jim; this ain’t no game. You hang back and keep quiet or I’ll do to you what I’d do to any other damn fool who was getting in my way—we square?”

Jim nodded. He fell into step beside the Indian. They slipped down an alleyway between the theatre and the general store.

“Who’d you kill in West Virginia that they want to string you up for?”

Jim stopped.

Mutt turned to the boy. “Your poster got here about three months before you did. Who did you kill?”

“A sonofabitch,” Jim said, walking again.

Mutt fell into step beside the boy. “Plenty of those still walking around,” the deputy said as they stepped out onto Main Street. A crowd was gathered in front of the general store. “Why’d you kill this particular one?’

“Got my reasons,” Jim said, happy to be on the other side of the sardonic grin for a change.

The Hanged Man

“All right, folks, everyone get back a ways!” Mutt shouted to the crowd. He gestured to a couple of the men who were in with the throng of onlookers. “Louis, Larry, you get these people back for me. Other side of the street, everybody!”

Jim moved behind the water trough and hitching post to the left of the general store. He watched as Mutt gestured to a woman and a girl in bonnets clutching heavy wicker baskets. Mutt knew Maude Stapleton, the bank president’s wife, and her thirteen-year-old daughter, Constance.

“You ladies were shopping in Auggie’s, right?”

The women obviously seemed uncomfortable in such close proximity to the half-breed. They nodded to the affirmative.

“Tell me what happened in there.”

Maude Stapleton cleared her throat and addressed him behind startling eyes of honeyed brown, almost gold. Mutt had never actually been this close to her before. Her hair was auburn, shot with hints of red-gold and silver, pulled from her face in a severe bun and held under her bonnet. Her skin was alabaster, like fancy china; her wrists and hands were pale too and fragile and perfect. Her features were strong; some men would have called her mannish in her demeanor. Those men would be fools, Mutt concluded. She was beautiful, strikingly beautiful, just not in the same old way. It took more than a lazy glance to see it in her. Her frame and figure were slight as well, but there was a wiry strength to her and she carried herself with a grace and an almost shrouded power that was very feminine to him right this moment. It was like standing next to a mountain lion pretending to be a desert hare. He shifted a little uncomfortably.

“Constance and I were just settling our account with Mr. Shultz when a ghastly spectacle of a man barged in.” She had a faint southern accent.

“Earl? Was it old Earl Gibson from up on Argent Ridge?” he asked.

“I have no idea who that is, Deputy, I’m sorry. He had a pistol in his hand and was shouting out absolute nonsense peppered with obscenity. He pointed the gun at us and I nearly fainted. He told us to get out and we did. He told poor Mr. Shultz to stay and to bring him … What was it he wanted, Constance?”

“Paraffin,” the girl said. She was her mother’s daughter, same eyes, wisps of lighter hair falling out of her bonnet. “Paraffin wax, all Mr. Shultz had. He said something about stopping something up.”

“It didn’t make much sense,” Mrs. Stapleton said. “The man was a mad as a hatter.”

“Could you tell if he had been drinking?” Mutt asked while he kept glancing at the store’s front door.

“Well, obviously he must have,” Mrs. Stapleton said. “How else would you explain such horrid behavior?”

“I mean, Mrs. Stapleton, did you smell it on him?”

She wrinkled up her face as if Mutt had just propositioned her daughter.

“I certainly would never approach a man like that and get close enough to actually smell—”

She was drowned out by the thunder of gunfire. Screams erupted from the crowd as onlookers scattered like roaches caught in a light. Mutt spun and shoved both women onto the ground, diving on top of them to cover them from the fire. Mrs. Stapleton’s bonnet was lost in the fall; her hair tumbled out everywhere in a tangled mess. She gasped when she realized she was only inches from Mutt’s face. Their eyes met and held. Her eyes reminded him of a deer for a second, moist, dark and wide; then something passed through her and suddenly he was looking into a mirror, at a hunter’s eyes, a predator’s eyes. It was his turn to suddenly draw breath. Her body shifted slightly beneath him, but their eyes remained locked. He raised himself up out of the muck and off Mrs. Stapleton. He crouched, covering them with the rifle.

“Thank you for your civic support, ladies,” Mutt said after a space of awkward seconds. “You just hurry on over to the over side of the street now, and I’ll go have a word with old Earl. Stay low. Oh, and Mrs. Stapleton…”

“Y-yes,” she said, turning her head back to look at the deputy as she was crawling away. The timid hare again, the banker’s wife.

“Sorry about the smell.”

The faintest ghost of a smile crossed her eyes. She took her daughter’s hand and they hurried out of harm’s way.

Mutt crouched as he moved out of the middle of the street and took up a position next to Jim’s water trough.

“That,” he said to the hiding boy, “was a shotgun. Auggie’s got one under the counter. I guess old Earl’s got it now. I hate shotguns.”

“What you planning to do?” Jim asked.

“Something stupid, I reckon.”

He wiped some of the street’s dirt off the Winchester, looked around to see if any townsfolk had moved up to help. They hadn’t. No one was going to stick their neck out for him.

“Let me help, Mutt,” Jim said.

The Indian smiled. Not funny, not cruel mixed with funny. Warm and full of surprise and appreciation. “What do you know about that?” the deputy muttered.

He passed Jim his pistol. The six-gun was heavy in the boy’s hand, but he’d handled the weight well enough before.

“Don’t move from this spot,” Mutt said. “Don’t shoot unless you got to. Earl’s a good man, just down on his luck. And for God’s sake, don’t shoot me. Ready?”

Jim nodded and steadied the gun on the post. Mutt cradled the rifle close to his chest and prepared to charge through the front door of the store.

It was silent all along Main Street. The thunder of the gun blasts had faded into the dry wind. The townsfolk watched mutely from the safety of cover, hidden behind rain barrels and wagons. Most expected the Indian to burst through the door and be knocked back out onto the street in a cloud of gun smoke and blood. Truth be told, so did Mutt. The town held its breath.

There was a sound, like a heartbeat, drumming fast and growing louder. It came from out past the edge of town, past the dry well, out by the cattle ranch. It echoed along the street, becoming more distinct as it rapidly grew closer and closer. Galloping, a horse’s hooves clattering in a wild, powerful run.

The horse appeared at the edge of Main Street in a cloud of desert dust. He was a bay stallion. The rider was crouched low, his gray, wide-brimmed Stetson held tight on his head by the stampede string under his chin. The rider’s face was half-covered by a tied kerchief to keep the dust and sand out of his nose and mouth. His gray barn coat fluttered like a moth’s wings as he spurred his mount on; faster, faster.

A shout went up from the crowd and then a cheer.

“It’s the sheriff! The sheriff is here!”

“About damn time,” Mutt said to Jim.

The rider reined his mount up beside the hitching post next to Jim and Mutt. Jim took the reins when they were tossed to him and looped them about the post. The rider climbed off the saddle with the smooth grace of someone who had lived most of his life on horseback. He pulled the bandana down around his neck and pushed the hat back off his forehead, shaking the trail dust off him as best he could.

He was a tall man, a good half foot taller than Mutt, and he had hair the color of desert sand. It was longish, slicked back from his face. He was handsome, in a simple kind of way—nothing fancy like the mayor. He had a week’s trail beard shadowing his jaw and it made him seem older than he really was. A gleaming silver star hung on the lapel of his dusty barn coat and a .44 was strapped to his right hip. He wiped his face with a gloved hand and looked around. Gray eyes flashed silver in the late morning sun.

“Jon,” Mutt said with a nod. “Nice entrance.”

“Thanks, Mutt. What is it this time? I heard the shots riding in.”

“Somebody’s in the general store, shooting off Auggie’s shotgun,” Mutt said. “Harry seems to think it’s Earl Gibson.”

“That don’t sound like Earl, even on a tear; that don’t sound like Earl at all.”

“I know. I was just about to go in there and have a discussion with him about that.”

“All by yourself?”

“Well, not too much help was forthcoming from our fellow citizens—”

“It’s a comfort to know some things never change. Who’s this?”

Jim turned to regard the sheriff. “I’m Jim. I’m a friend of Mutt’s.”

The sheriff frowned and turned to Mutt, who said nothing, only shrugged, then back to Jim. He pulled off a glove and extended a dirty, calloused hand to the boy.

“Jon Highfather. I’m sheriff in these parts. Not too many claim Mutt as a friend and he don’t cotton to most that do. So, it’s always nice to meet someone who makes the cut.”

Jim shook hands. Highfather looked at the pistol in Jim’s other hand, then to Mutt.

“He’s my deputy,” Mutt said. “I found him out in the desert.”

“Your what?” Highfather said.

“Well, I needed someone watching my back and I couldn’t wait around anymore for you to come riding in making fancy entrances.”

“Picking up strays again, Mutt?”

“Look who’s talking.”

Highfather untied the leather thong around his leg and then unbuckled his gun belt. He turned back to his horse and rummaged in his saddlebags. He took out a large metal key ring with dozens of keys. He selected one and offered it to Mutt, keeping his back to the store’s windows.

“This is the key to Auggie’s back door. I want you to wait until I get inside and then get back there and open it as quiet as you can. It sticks a bit.”

“Will do, boss. What if Earl is crazy as a jumping bean and just blasts you?”

Highfather stared at his deputy incredulously.

“Oh yeah, right. ‘Not your time.’ … I forgot.… Sorry.”

“Just give me a minute to get the medicine show rolling, okay? And you, Deputy Jim, I want you to stay right there and cover us, okay?”

Jim nodded, knelt and adjusted the gun against the post again. Highfather laid his gun belt over the hitching post and walked up onto the sidewalk. He rapped loudly on the store’s door.

“Earl? Earl, you in there? It’s Jon Highfather. I need to talk to you.”

“You go on now, Jon!” a shaky voice called out from inside. “You don’t know what they been pourin’ in my ears, down my throat, Jon! You ain’t seen—”

A disheveled old man with wild gray hair and whiskers, dressed in filthy clothes, appeared in the window. He was holding a squat sawed-off double-barreled scattergun to the chest of the portly walrus-looking man Jim had seen sweeping up when they had entered town. The old man’s eyes were glazed over with fear.

“Go on now, Jon! I don’t want to hurt anyone, but I got to plug up my ears, sew up my mouth. I can’t stand it anymore!”

“Now Earl, you know I can’t just walk away here. Why don’t you put the gun down?”

Auggie Shultz, the walrus shopkeeper, looked scared too, but was doing a good job of controlling it.

“Jon,” Auggie said through a thick accent. “He’s shot up the store, but no one is hurt. I think he’s sick—”

Earl thumbed back the hammers on the shotgun. Sweat crept down his face.

“Shut up! Shut up! They did this to me; they did it! The singing thing in the mountain!”

Highfather raised his arms above his head. “Earl, I don’t have any guns, see? I’m going to come in there and we can talk, okay, Earl? Just talk.”

The old man and his hostage disappeared from in front of the large window. Highfather looked back at Mutt and Jim, opened the door and stepped inside.

Shultz’s General Store usually smelled of talcum, sawdust and sausages. Today it was gunpowder and the sour smell of vinegar. The pickle barrel was dead, a massive hole blasted in it, and green juice and dills covered the floor. Several of the shelves behind the counter that contained Auggie’s pharmacopeia canisters were torn apart, their contents scattered across the store. Bins of chemicals and compounds were strewn everywhere.

“Shut the door; they can hear us when the door is open,” Earl whispered from the shadows near the counter.

“‘They’ who, Earl?” Highfather asked as he closed the door. The small bell on the jamb jingled.

The old man jumped, his eyes wide in fear, and he pressed the gun into Auggie’s chest hard enough to make the shopkeeper grunt in pain. “Bells, they talk in silver bells! They’re eating my memories; I can’t remember Daisy’s face no more, Jon; they done gone and ate Daisy’s face from me!”

Highfather swallowed hard and stepped closer to the old man. “I understand Daisy was a fine woman, Earl. We’re all powerful sorry she’s gone, but that isn’t Auggie’s fault, now is it?”

Earl sobbed; he loosened his grip on the gun.

Auggie turned so he could see his captor’s face. “You know I understand how it is to lose someone, Earl, yes? When Gertie passed, I thought I had died along with her. I still wish I had most days.”

“But … but isn’t that her singing, upstairs? Singing along with the music box?” Earl groaned. Auggie’s face paled, his mouth opened, but nothing came out.

“There … there’s no one singing, Earl,” Highfather said softly. “Gert’s passed. Daisy is gone too. I’m sorry, but that is the way of it. People die. It’s sad but—”

“Shut up!” Earl screamed. “You dumb sumbitch! You don’t know what they do up there on that mountain, do you, Sheriff? It’s tossing and turning! It eats the heart of the world, like a worm burrowing an apple! Maybe the preacher’s right and my faith is just shivering, weak—is it wrong for me to try to keep them from hollowing me out from inside? I should just blow all of you stupid bastards back to Kingdom Come, while it’s still there! Before they burn down Heaven and feast on the corpse. Maybe we should all die now, better that way!”

Highfather edged closer. He managed to maneuver the old man so his back was to the counter.

“People die, Earl, up on the mountain, down in the valley; everyone dies.”

“Everyone but you, Jon,” the old man muttered.

Everyone but me,” Highfather said. “You’ve heard the stories, haven’t you, Earl? The stories about me?”

“They say you sold your soul to the Devil, Jon; that’s what they say.”

Highfather moved closer to Earl. He held the old man’s gaze with his voice, his shimmering gray eyes. Behind them was a faint click. Earl didn’t notice it.

“I’ve heard that one too, Earl, heard all of them. They tried to kill me back in the war, Earl. Strung me up on the end of a hangman’s rope. Three times, want to see?”

Highfather pulled back the bandana and tugged down the collar of his shirt. Three lines of ugly, striated scars crisscrossed each other around the sheriff’s neck. Their gruesome orbits intersected and blurred into pale raised scar tissue at different points all around his throat.

“See, Earl. That shotgun can’t kill me. Nothing on this earth can kill me. Now you give it to me right now, or I swear on the gallows tree, I’m going to take it away from you.”

Earl froze, his eyes locked on the scars. “Dead man, they say you’re a walking dead man.… Not your time—”

Highfather grabbed the shotgun by the smooth, oily barrel. Earl yanked, screamed and pulled the triggers. Highfather’s thumb jammed one of the hammers, even as he twisted to avoid the blast directly in front of him. The shotgun’s roar filled the universe, filled everything, with heat and light and acrid smoke. Highfather could barely perceive anything. He felt the pain in his hand and a burning, then numbness in his side. The shotgun clattered to the floor and Auggie was diving for it. Earl was in Highfather’s face, pale, with tears running down his rheumy eyes.

“See,” Highfather croaked, “told you.”

Mutt was over the counter, spinning Earl around and pinning his arms. The boy, Jim, came crashing through the front door, the Colt steady in his hands as he swept the place left to right.

The Indian looked at Highfather. “You okay? You hit?”

Highfather could barely make out the words over the pain and ringing in his ears, like a water glass vibrating, humming. He looked down to see a smoking hole in his barn coat. It went in about six inches above his belt and exited in the back. His shirt was blackened on that side and the flesh underneath was blistered and sore, but the slug had passed by, missing cutting him in half by inches. If the other barrel had fired, it would have ripped right through him.

“I’m okay. Good thing he wasn’t firing shot, and I managed to block the right hammer, huh?”

“Luck still holding,” Mutt said. “You count on her being there too damn much.”

“Not my time yet,” Highfather said.

“Thanks, Jon,” Auggie said, eagerly pumping the sheriff’s hand while Highfather pulled up his collar and once again hid his neck. “The poor old fella is balled up something terrible, yes?”

Highfather winced, but tried to ignore the pain that was beginning to filter into his nerves from the powder burns on his flank. He shook Auggie’s hand and steadied himself on the counter.

“We’ll be pressing charges for the firearms discharge in the town limits and the assault, Auggie. Do you want to file any charges for the destruction of property?”

“I know I should, but Gert always says to turn the other cheek. So, no, I will not press the charges.”

“I’m sorry we had to bring Gertie up, Auggie. He was just so … well, I hope you understand it weren’t anything speaking to her character at all. I was just trying to spook him.”

“No, Jon, no. You are good man. Gert, she always like you.”

Mutt led Earl outside. The old man was still raving, but when he looked out onto the street amidst the whoops and cheers of the townsfolk he seemed to pause, as if he was seeing something, hearing something, fitting the pieces in his head.…

“Jon, you’ve got to stop them! Stop them, I tell you! They sing terrible songs, Jon, horrible songs! The worms! They’re coming, Jon. Worms, eating to the core of us. They eat life, they will eat up time and reason and then they will eat the light! They’ll eat the light, Jon! Please, Jon, you’ve got to stop them, stop me, stop him!”

Mutt pulled Earl aside, wrestled his arms behind him, again, and applied a pair of iron cuffs to his wrists.

Highfather placed a hand on Mutt’s shoulder. “This is the third person off the ridge to go bughouse crazy in the last few weeks.”

The Indian nodded as he struggled to keep Earl from twisting loose of his grasp. “You think someone is running bad hooch up there again?”

“Don’t know. Earl’s breath don’t smell like whiskey; neither does his clothes. I want you to head up there to the ridge tomorrow. See if anyone is brewing up anything they shouldn’t be.”

“Get right on it, boss,” Mutt said, then,“What about the kid?”