Written by Ada Palmer

Written by Ada Palmer

The more I talk to other authors about craft the clearer it is that novelists use a huge range of different planning styles. People talk about “Planners” vs. “Pantsers,” i.e., people who plan books and series in advance vs. people who plunge in and write by the seat of their pants. Each category contains a spectrum, for instance people who plan just the major plot points vs. people who plan every chapter. But even then, authors who are improvisational about some parts of storymaking can be very much plotters when it comes to others.

Characters, plot, and setting, or—for genre fiction—world building are very visible. They tend to be what we talk about most when geeking out about a favorite book: a plot twist, a favorite character’s death, the awesome magic system or interstellar travel system. Sometimes an author will develop a world or characters in detail before writing but not outline the chapters or think through a plot. I develop the world first, then develop characters within the world, and then make my chapter-by-chapter outline. But even those stages of world building and character aren’t the first stage of my process. I want to talk about some of the less-conspicuous, less-discussed elements of a novel which, I think, a lot of writers—pantsers or plotters—begin with.

“Too like the lightning which doth cease to be/ Ere one can say ‘It lightens’.”

The Terra Ignota series was born when I first heard these lines while sitting through a friend’s rehearsal of Romeo and Juliet after school. The speech didn’t give me plot, characters, world, or setting—it gave me structure. In a flash, I had the idea for a narrative which would revolve around something incredibly precious, and beautiful, and wonderful, something whose presence lit up the world like lightning in the night, that would be lost at the midpoint of the story. The whole second half would be about the loss of that thing; the world and all the characters would be restructured and reshaped because of that one, all-transforming loss. All at once I could feel the shape of it, like the central chords that structure the beginning, middle, and end of a melody, and I could feel the emotions I wanted the reader to experience in the brightly-lit first part, at that all-important central moment of loss, and in the second half. It was so intense I teared up.

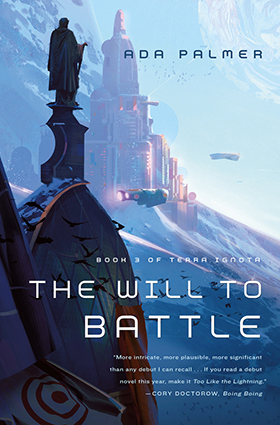

I had no idea at the time whether this series would be science fiction or fantasy, Earth or another world, past or future, but every time I re-read or re-thought that line, I felt the structure vividly, and the power it contained. Over the following years I developed the world and characters—what could be so precious, and what kind of world could be ripe to be transformed by its loss. At last I sat down to outline, working out, chapter by chapter, the approach to that central moment, and its consequences. Now that The Will to Battle is coming out, and I’m working on the fourth and last book of the series, I’m sticking to that outline, but even more I’m sticking to that structure, and feeling that emotional finale that came in the flash so long ago finally taking on a form that will let other people feel it too.

I’ve heard a lot of authors use different words to discuss this sense of structure: knowing the beats of a story, knowing where it’s going, knowing the general shape, knowing the emotional arc. Some sit down to write with a very solid sense of structure but no chapter-by-chapter plan. Some—like me—use this sense of structure, not only to write an outline, but to shape the world and characters. And some writers plunge into chapter one without a sense of structure, working out the emotional beats as the character actions flow. And I think this difference—when, during the process, different authors develop the structure of a book or series—is just as important as the difference between outlining vs. not outlining, or world building in advance vs. world building as you write.

You can design a world and characters and then think about whether a tragic or triumphant ending would be best for them, or you can have a tragedy in mind and then design the characters to give maximum power to that tragedy, with very different results. But since we rarely discuss structure as a separate planning step, I think many developing writers don’t consciously think about structure as separate from plot, and don’t think about when the structure develops relative to other ingredients. After all, you can sit down to outline—or even to write—and only discover at the end that the story works well with a tragic ending, or you can feel tragedy coming from the beginning, and plan the chapters as steps toward that inexorable end.

Of course, sometimes genre brings some elements of structure with it. Think of Shakespeare sitting down to write a tragedy vs. a comedy—some of the beats of these structures are pre-set, but Shakespeare varies them by deciding how early or late to resolve the main romantic tension, or whether the most emotionally-powerful character death will come at the very end or at the two-thirds point so the last third can focus on mourning and aftermath. Shakespeare thinks a lot about structure, which is how he can get you with structural tricks, like how Love’s Labour’s Lost seems to resolve the romantic tension about half-way through and then disrupts it at the end, or how King Lear has so many tragic elements that you start to feel there has been enough tragedy already and there may not be more coming, a hope Shakespeare then uses to powerful effect.

Modern genres too contain these sorts of unspoken structural promises, such as disaster movies, which promise that the plucky central characters will make it through, or classic survival horror, which used to promise that the “good” characters would live while the “flawed” characters would be the ones to die. One of the major reasons that the first Japanese live action horror series that saw U.S. releases—like The Ring—seemed so stunning and powerful to horror fans was that their unspoken contract about who would live and who would die was different, so the deaths were extremely shocking, violating traditional unspoken structures and thus increasing the shock-power of the whole. Varying the expected structural promises of genres like epic fantasy, particularly regarding when in the narrative major characters die, has similar power.

Another major ingredient which different authors plan out to different degrees and at different stages is voice. Is the prose sparse (a sunny day) or lush (fleecy cloud flocks flecked the ice-blue sky)? Are the descriptions neutral and sensory (a bright, deep forest) or emotional and judgmental (a welcoming, unviolated forest)? Is there a narrator? One? Multiple? How much does the narrator know? Are we watching through the narrator’s eyes as through a camera, or is the narrator writing this as a diary years later? I’ve spoken with people who have started or even completed drafts of a first novel without ever actively thinking about voice, or about the fact that even very default choices (third person limited, past tense but movie camera type POV, medium-lushness prose) are active choices, as important as the difference between an ancient empire and a futuristic space republic in terms of their impact on reader experience. We’re all familiar with how retelling a fairytale from the villain’s point of view or retelling a children’s story with a serious adult tone can be immensely powerful, but any story, even a totally new one, can be transformed by a change in voice. Often the stories I enjoy most are the ones where the author has put a lot of thought into choosing just the right voice.

Terra Ignota’s primary narrator, Mycroft Canner, has a very complicated personality and idiosyncratic narrative style, so central to the book that I don’t exaggerate when I say that switching it to being fantasy instead of science fiction would probably make less difference than changing the narrator. But while many people ask me about how I developed this narrative voice, few ask about when I developed it: before or after world building, before or after plot. Mycroft Canner developed long after the structure, and after the other most central characters, but well before the plot; at about the midpoint of developing the world. Mycroft’s voice had a huge impact on how world and plot went on to develop, because (among other things) Mycroft’s long historical and philosophical asides mean that I can convey a lot of depth of the world and its history without actually showing all the places and times that things took place. This allows a very complicated world to be portrayed through a comparatively limited number of actual events—a high ratio of setting to plot. With a more clinical narrator I would probably have had to have more (shorter) chapters, and portrayed more actual events.

Mycroft’s very emotional language acts as a lens to magnify emotional intensity, so when a scientific probe skims the surface of Jupiter I can use Mycroft’s emotional reaction to make it feel like an epic and awe-inspiring achievement. If I had a less lush, more neutral style, I would have to do a lot more event-based setup to achieve the same kind of emotional peak, probably by having a character we actually know be involved in creating the probe. Movies use soundtracks to achieve the same thing, making an event feel more intense by matching it with the emotional swellings of the music, and movies with a grand musical score create very different experiences from movies with minimalist soundtracks that have to gain their intensity from words, events, or acting.

Voice—in Terra Ignota at least—also helped me a lot with the last story ingredient I want to talk about here: themes. Stories have themes, and these can be totally independent of plot, characters, all the other ingredients. Let’s imagine a novel series. We’ll set it on a generation starship (setting). Let’s give it two main narrators, the A.I. computer and the ghost of the original engineer (voice), who will be our windows on a cast that otherwise changes completely with each book (characters). Let’s say that there will be three books showing us the second, the fifth, and the last of the ten generations that have to live on the ship during its star-to-star voyage, and each book will be a personal tragedy for those characters—the first with thwarted love, the second with some people who dream of launching off on their own to explore but have to give it up to continue the voyage, and the third with the loss of someone precious just before the landing (plot)—but that the whole voyage will be a success, juxtaposing the large-scale triumph with the personal-scale tragedies (structure). Even with so many things decided, this story could be completely different if it had different themes. Imagine it focusing on motherhood. Now imagine it focusing heroic self-sacrifice. Try techno-utopianism. The will to survive. Plucky kid detectives. The tendency of tyranny to reassert itself in new forms whenever it’s thwarted. Art and food. The tendency of each generation to repeat the mistakes of its past. The hope that each generation will not repeat the mistakes of its past. Try picking three of these themes and combining them. Each one, and each combination, completely reframes the story, the characters, and how you can envision the events of the plot unfolding.

So, returning to plotter versus pantser, when in planning a story do you choose the themes? For some writers, the themes come very early, before the plot, possibly before the genre. For others the themes develop along with the characters, or with the voice. Some don’t have a clear sense of themes until they come to the fore at the very end. Some genres tend to bring particular themes with them (the potential of science in classic SF, for example, or the limits of the human in cyberpunk). And voice can make some themes stronger or weaker, easier or more possible.

In Terra Ignota a number of the major themes come from Enlightenment literature: whether humans have the ability to rationally remake their world for the better, whether gender and morality are artificial or innate, whether Providence is a useful way to understand the world and if so what ethics we can develop to go with it. Mycroft Canner’s Enlightenment-style voice makes it much easier to bring these themes to the fore. Other themes—exploration, the struggle for the stars, how identity intersects with citizenship, how the myth of Rome shapes our ideas of power, whether to destroy a good world to save a better one—I bring out in other ways. Some of these themes I had in mind well before the world and characters, so I shaped the world and characters to support them. Others emerged from the world and characters as they developed. A couple developed during the outlining stage, or turned from minor to major themes during the writing. In that sense even I—someone almost as far as you can get on the plotter end of the plotter-pantser scale—can still be surprised when I discover that a theme I expected to come to the fore in chapter 17 comes out vividly in chapter 8. Knowing the themes helped me in a hundred different ways: Where should this character go next? If she goes here, it will address theme A, if she goes there theme B… right now theme B has had less development, so B it is!

All three of these ingredients—structure, voice, and themes—could be the subject of a whole book (or many books) on the craft of writing. For me, this brief dip is the best way I can think of to express how I feel about the release of The Will to Battle. Yes it’s my third novel, but it’s also the first part of this second section of Terra Ignota, the pivot moment of the structure, when we’ve lost that precious thing that was “Too like the lightning” and have to face a world without it. It’s the moment when other people can finally experience that sequence feeling that I felt years ago, so intense and complicated that I couldn’t communicate it to another human being without years of planning and three whole books to begin it, four to see it to its end. It feels, to me, completely different from when people read just book one, or one and two. And that’s a big part of why I think, when we try to sort writers into plotter or pantser, the question “Do you outline in advance?” is only one small part of a much more complicated process question: Setting, plot, characters, structure, voice, themes: which of these key ingredients come before you sit down to write the first chapter, and which come after?

Order Your Copy

Order Your Copy

Follow Ada Palmer on Twitter, Facebook and on her website.