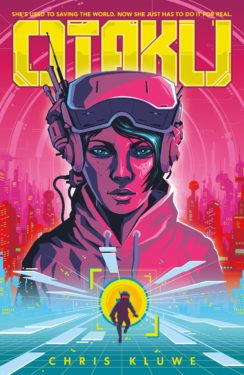

Struggling with all this down time? A lot of us are using our extra free time to refine and explore the literary worlds we have created for ourselves. Otaku author Chris Kluwe swung by the blog with some tips to help make sure your novel doesn’t get bogged down in the too many details.

Struggling with all this down time? A lot of us are using our extra free time to refine and explore the literary worlds we have created for ourselves. Otaku author Chris Kluwe swung by the blog with some tips to help make sure your novel doesn’t get bogged down in the too many details.

By Chris Kluwe

One of the most difficult things about creating a fictional story, especially a science fiction or fantasy story, is coming up with a believable world for the characters to inhabit that is also uniquely separate from our own. Too fantastical and the reader might be left struggling to catch up, too realistic and the element of wonder is lost; too much detail can cause infodumps to drown the plot, too little and confusion obscures what’s important. Threading that fine line is a tough skill to develop, and while I don’t claim to be a master at it, I feel there are several foundations that if kept in mind can really help bring your world to life.

- Your World Has To Make Sense

Now, when I say “your world has to make sense”, it doesn’t mean that it has to be ultra-realistic with every electron orbiting exactly as physics requires. No, what this means is that when you’re building a world, no matter how strange your rules for that world are, those rules should be internally consistent with each other.

If a reader witnesses the result of one interaction (a dragon breathes fire, incinerating some poor chapter one redshirt, but has to take a moment to recharge afterward), they should feel confident that will remain true for further interactions (the next time a dragon appears, the reader knows that the dragon will breathe fire, but there’s an opening the protagonist can exploit to slay the dragon/stay alive/run home wondering why they didn’t just take up a masonry apprenticeship like their mother wanted).

One of the first steps in building a world is trust. The reader must be able to trust that the information you’re presenting will remain consistent throughout the length of the tale, allowing them to establish a coherent frame of reference.

If your dragon suddenly shows up in a spaceship blasting dubstep while raining nano-missiles on some hapless knight, unless you can really sell surreality, most readers are going to check out.

2. Your Primary Interactions Don’t Inhabit The World

Primary interactions are the easy part of writing a story. What’s a primary interaction? To continue our example from earlier, a fire-breathing dragon with a convenient recharge window appears! The hero must defeat it by constructing ever more elaborate architectural traps after rediscovering their passion for masonry! Baddabing, baddaboom, the reader knows exactly what’s in store (exotic buildings collapsing on oversized winged newts), but this doesn’t make your world feel inhabited.

What makes your world feel alive is the secondary, tertiary, and if you want to get really frisky, quaternary interactions going on beneath the surface.

In a world where fire-breathing dragons exist, what does that mean for building construction? (lots more demand for masons!) Is there a thriving trade for juvenile dragons to use as firestarters/blacksmith forge replacements/living flamethrowers? (Heya Captain Vimes!) Did human society prioritize different technological advancements to deal with threats from the sky? (Radar installations and ranged weaponry, oh my!) Are there lawyers representing adventurers suffering from the effects of asbestos-lined suits of armor? (You better believe it!)

All of these are things you need to spend hours thinking about, days carefully plotting out the myriad interactions of, and then seconds realizing that ninety-nine percent of the details you’ve painstakingly inserted into a spreadsheet are things the reader never needs to know and can instead be illustrated by something like the following:

“Dozens of cheap broadsheets advertising the services of Parry H. Larker, self-declared ‘equipment tort specialist’ to ailing dragonhunters, blanketed the path Apprentice Jana found herself trudging each day on her way to work. The broadsheets were not quite as annoying as the piles of ill-fitted stonework that always seemed on the verge of collapsing around her, which paled before the piercing wail of the alarm sounding another possible attack from above. Shaking her head, Jana ignored the frenzied calls from a squad of crossbowmen rushing to an anti-air tower and focused on putting one foot in front of the other. Dragons hadn’t taken down TKTKTK (use this when you can’t be bothered to think of a name but need to keep writing) in all the years she’d been alive, and it was highly unlikely today would be the exception.”

Baddabing, baddaboom, now your world feels alive.

3. Your World Serves Your Characters, Not The Other Way Around

So, you came up with an amazing system of magic/technology/column engraving that’s going to blow everyone’s minds.

Congratulations! Here’s a handy flowchart to decide whether or not your reader needs to know all about it.

Does it advance your plot and characters?

- If “no”, focus on your characters.

- If “yes”, find the most unobtrusive way possible to deliver relevant information that doesn’t break the flow of the story, then get back to your characters.

Technology, magic, folklore, fiction – all of these things are ways we try to make sense of the world and our reactions to it, and the key point there is “our.” Every story is a human story (at least until the machines replace us), and if you want your reader to buy into what you’re selling, the human element has to be front and center.

All the best science fiction and fantasy I’ve ever read has been, at its core, a story about what we’ve done, what we’re doing, and what we might do, and if there isn’t something relatable to the reader’s perception of reality they’re going to tune out.

If, in our example, you spend all your time spent figuring out exactly how each stone, carefully fitted to interlock with each of its neighbors in an intricately designed marvel that requires no mortar whatsoever and is a new revolutionary technique that the entire world would benefit from– maybe you should go get your engineering degree (“I KNOW, THANKS MOM”). None of it matters if you can’t get your reader past chapter one, so make sure your characters are what you’re focusing on.

Everyone can tell you how Harry Potter made them feel. No one gives a shit how nonsensical that entire system of magic actually is. (Seriously, a world where people can legit turn themselves into other people and identity theft isn’t a number one priority?!) Your characters make the story. The world is stage setting around them.

4. Break Your World’s Rules If They Need To Be Broken, But You Better Be Really Damn Sure About It

This one’s pretty self-explanatory, really. If your third act is the dragon and the mason/worldsaving aficionado coming together for a Broadway dance routine, it better hit all the high notes or else Kirkus is going to fucking savage you.

Chris Kluwe is the author of Otaku and Beautifully Unique Sparkleponies blah blah blah seriously why are you still reading this part I expected you to tune out after the first pretentious paragraph.

Order Otaku Here: