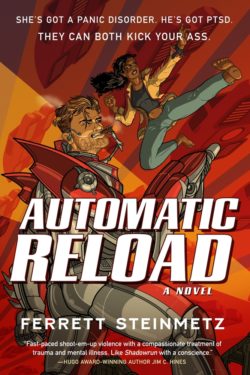

Ferrett Steinmetz’s quirky, genre-mashing cyberpunk romance Automatic Reload: a high-octane adventure about a grizzled mercenary with machine gun arms who unexpectedly falls in love with a bio-engineered assassin.

Ferrett Steinmetz’s quirky, genre-mashing cyberpunk romance Automatic Reload: a high-octane adventure about a grizzled mercenary with machine gun arms who unexpectedly falls in love with a bio-engineered assassin.

In the near-future, automation is king, and Mat is the top mercenary working the black market. He’s your solider’s solider, with military-grade weapons instead of arms…and a haunted past that keeps him awake at night. On a mission that promises the biggest score of his life, he discovers that the top secret shipment he’s been sent to guard is not a package, but a person: Silvia.

Silvia is genetically-altered to be the deadliest woman on the planet—her only weakness is her panic disorder. When Mat decides to free her, both of them become targets of the most powerful shadow organization in the world. They go on the lam, determined to stop a sinister plot to create more super assassins like Silvia. Between bloody gunfights, rampant car chases and drone attacks, Mat and Silvia team up to survive…and unexpectedly realize their messed up brain-chemistry cannot overpower their very real chemistry.

Please enjoy this excerpt of Automatic Reload, available 07/28/20.

Act 1

Reluctantly Crouched at the Starting Line

I’m not a fan of human arms. That quarter-second delay between visual confirmation and trigger finger movement is, quite literally, a killer in a combat situation. Compare your sluggish meatware to the baseline friend-or-foe targeting routines on my Zentrine-Gauss upper-limb armed prosthetics—they have their own sensors, and can put three rounds into an emerging hostile in under .04 seconds. Even if you have your gun aimed at me when I walk into your line of fire, I’ll outdraw you, with computer-targeted accuracy, with .21 seconds to spare. You’ll be dead before either of us realizes what happened.

So to survive, you must realize this: the human body is the least reliable component of your combat equipment. The more you can minimize its influence, the better.

Which leaves good maintenance as the only thing that will protect you.

Yet the sole advantage your organic appendages have over my sweet darlings Scylla and Charybdis—yes, I nickname my limbs—is that your meat-arms are self- lubricating and self-repairing. Your daily maintenance consists of pull-ups and a salad.

Me? I spend hours fieldstripping my arms and legs, clearing out debris that could jam the delicate machinery. I recalibrate my artificial musculature. I optimize the computerized routines that govern Scylla and Charybdis— their baseline friend-or-foe identification routines take .04 seconds to acquire a noncombatant target, but I’ve shaved my capture-to- fire time down to .0125 seconds, and my onboard computers can differentiate between happy children and gun-toting criminals with dwarfism.

It’s the little details that matter.

Yet even if you do proper maintenance, you must do your pre- combat prep then stow your ego away. Too many body-hackers tether their self-worth to their in-combat contribution—if they don’t fire a few bullets manually, they figure they’re not real soldiers. These assholes get themselves killed, relying on their high- latency nervous system.

If you do it right, the fighting’s all but done before you arrive at your drop zone. You tune your reaction packages for the killing ground, you ensure your armed prosthetics are combat-ready, and you let the computers do the work.

Case in point: two men just died while I dictated this sentence.

The kidnappers I’m engaged with now—whoops, there goes a third one—are not, it must be said, particularly bright. The smartest kidnappers in Nigeria stopped when they realized the global fuel shortages were forcing oil companies to cut out unwanted expenses like, say, ransoms paid to kidnappers who targeted petroleum workers. The middling kidnappers gave it up when Aishat Njeze, current managing director of the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, started cracking down on kidnappers with bloody hi-tech reprisals.

These dumb motherfuckers kidnapped Aishat Njeze’s daughter. That poor kid’s eleven years old, the worst age to be kidnapped— old enough to understand what’s going on, young enough for the trauma to kick her right in the formative stages. If I don’t get her out soon, little Onyeka’s in for years of desensitization therapy.

So here I am, a one-man rescue squad sweeping through rusted sheds in the Niger Delta’s ankle-deep silt. Which is a shame, because I love Nigeria—Lagos is a friendly city, almost as nice as my hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, and there are even some really scenic views to be had from the Niger River. But dirt-poor brutes don’t take a kidnapped kid to places the Nigerian tourist board would approve of. I’m watching the numbers tick up on my read- outs as Scylla and Charybdis auto-target and kill five kidnappers in under forty-five seconds.

(I should say “disable,” not “kill”; my sensors have not verified these men’s deaths, only confirmed these former opponents are sufficiently maimed to be combat-irrelevant. Too many body- hackers get off on tracking their exact body counts—but me? As a drone pilot, I not only had to call in air strikes but had to circle the kill zone for hours afterwards, watching dismembered bodies rot in case their terrorist friends showed up to bury the corpses. I am done with watching corpses. So my IFF routines mark anyone unable to fight back as “disabled”—even though, knowing how high I’ve dialed in the mortality factors for Scylla and Charybdis, they’re probably dead.)

We’re now a minute into the kill box. I started the assault just as dawn glimmered over the Niger’s muck-slick waters; the kid- nappers are realizing someone big has come for them. My sensors track movement behind the soft wood and tin walls, assign high probabilities to which folks are going for their guns and which ones are diving for cover.

Less ethical hackers have their IFF routines set to fire through cover. But I won’t take any chances harming innocents in their houses. If these bozos emerge to snap off a shot at me, they’ll find a bullet smashing through their brain long before their slow, slow nervous system pulls the trigger.

As my ground routines scan for little Onyeka’s biosignatures, I have time to compile a partial list of items I personally would have gotten around to before kidnapping a politician’s daughter:

- a drone net to warn me of incoming hostiles, as opposed to the two guys chugging banana beer outside the perimeter

- automated turrets keyed to exclude white-listed biosignatures, ready to fire on any hostile

- networked subvocal implants among my commanders on a tight-beam, encrypted frequency, instead of crappy text- message codes that got cracked by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation

- mines, or at the very least buried grenades, to stop me from sauntering through their compound (Would it kill them to at least try digging a good old-fashioned punji stake pit?)

- a bucket of fine (I’m not saying it’s a great plan, but it’s at least possible some errant dust might work its way past my environmental seals to clog a vital servo and throw off my targeting systems.)

But I suppose if these guys had the money for non-sand-buckety tech, they wouldn’t have gone for the Hail Mary pass of kidnapping Aishat Njeze’s daughter. Nigeria as a whole is thriving in the new world economy, but this is the starving part.

I don’t like people living in poverty. These thugs are skeletal, scabbed, overwhelmed. I feel sorry for them—

until I remember there’s a crying girl sobbing into duct tape, wearing the most adorable bow tie and blue vest jacket, held hostage somewhere in these shoddy huts. I’d seen the footage of her kidnappers pulling up in a rusty van to yank her off the street on her way to school.

She’d had two human guards—antiquated meat-technology. Njeze’s daughter Onyeka had watched these assholes murder her protectors; that’s not something any kid should have to experience. Each passing minute scrapes deeper scars into her psyche.

Scylla kicks off another three rounds. An eighth person gets sorted into the “disabled” column. And as Scylla and Charybdis clear the path, I fine-tune their scanners, adjusting for the unexpectedly damp morning fog, homing in on poor Onyeka—

A ragged kid in a tattered Cleveland Cavaliers T-shirt emerges, hands up. My IFF routines switch to manual intervention, identifying the object in his hand as a harmless Apple cell phone, asking if I wish to disable.

Kid’s lucky I’ve configured my software to accept surrenders. “Speak your piece.”

The kid trembles. He’s emaciated, his dark skin prickling with fear-sweat. He turns the phone towards me to show it’s on speakerphone—

But the button is green underneath his thumb, as opposed to the red “disconnect” icon.

It’s an inverted speakerphone. A dead-man’s call.

“If you do not leave,” he says in a quavering adolescent voice, “we will shoot the girl in the head. If this call disconnects”—he mimes dropping it—“we will shoot the girl in the head. Your only hope to keep her alive is to leave.”

I smile.

That’s the first smart thing they’ve done.

Copyright © Ferrett Steinmetz 2020

Pre-Order Your Copy

Ooooooh I want to read MORE!!!