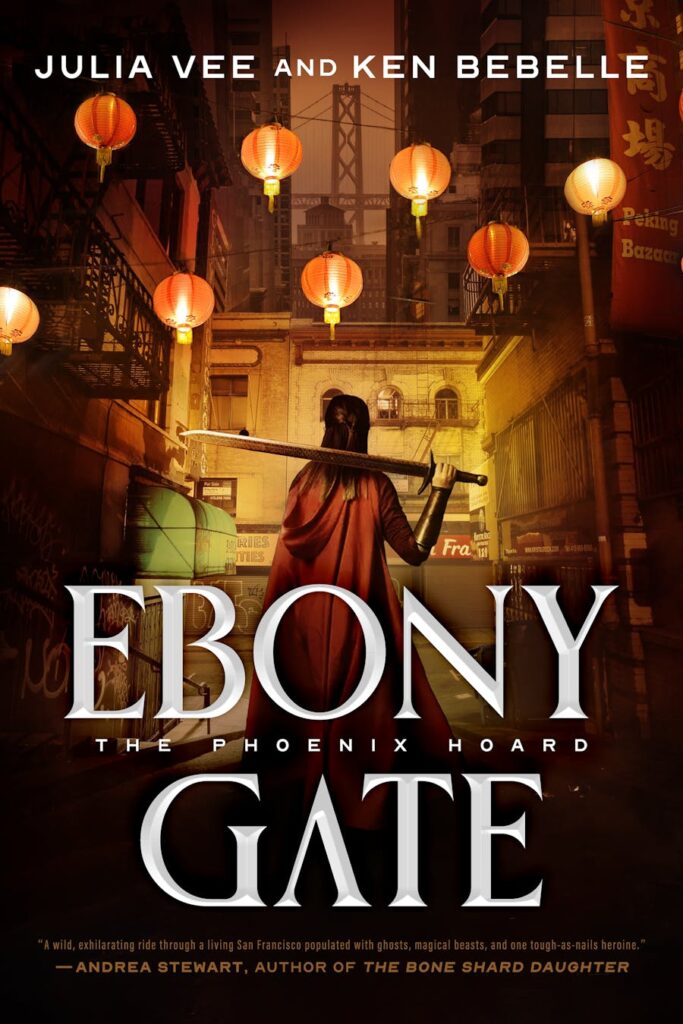

Julia Vee & Ken Bebelle wrote a book that’s like female John Wick with dragon magic and it’s called Ebony Gate and guess what! It’s out TODAY. We actually have Julia & Ken with us as special guests for Dragon Week, so check out their scholarly article on rituals of dragon worship, and then check out their high octane urban fantasy full of magic and assassins!

Julia Vee & Ken Bebelle wrote a book that’s like female John Wick with dragon magic and it’s called Ebony Gate and guess what! It’s out TODAY. We actually have Julia & Ken with us as special guests for Dragon Week, so check out their scholarly article on rituals of dragon worship, and then check out their high octane urban fantasy full of magic and assassins!

Check it out!

A Brief Description of Rituals to Worship Chinese Dragons by Julia Vee & Ken Bebelle

Make Your Annual Pilgrimage to a Local Dragon King and Dragon Mother Temple For Blessings

Dragon King and Dragon Mother temples dot the Asian countryside. If you are in the northern reaches of China, get yourself to the Heilongdawang Temple (literally “Black Dragon Great King”) located in Longwanggou (“Dragon King Valley”) in Shaanxi province where you can njoy six days of festivities.

Modern Chinese scholars note that folkloric traditions and religions are having a revival.1 And why not? Festivities for the Great Black Dragon King include opera, dancers, circus performers, games, fireworks, and of course, gambling. This particular dragon king is more highly regarded than other local dragon kings because of his imperially conferred official title–the Marquis of Efficacious Response (Lingyinghou, 灵应侯).2

The Heilongdawang festival draws hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, all ready to donate generously to the temple coffers, burn incense, and otherwise eat copious quantities at the food stalls.

Or you can participate in a rain-summoning ceremony. In the drought-prone north, one ritual to summon rain included “casting tiger bones into a pool of water in order to scare dragons into flight, thereby creating rainclouds.”3

If you are in southern China, on the eighth day of the fifth month on the lunar calendar, you can join in with over a hundred thousand pilgrims to visit the Dragon Mother Temple in Guangdong. This temple sits along the Xijiang River and leans against Wulong (Five Dragons) Mountain. The area is known as the Pearl River Delta, and Dragon Mother devotees are spread widely across the West river and into Hong Kong and Macau. The Lung Mo temple on Pengchau island (Hong Kong) is situated on the beach.

The origins of the Dragon Mother reach back longer than the established official story, which goes something like this:

There was a young woman named Wen from Wuzhou. One day while washing clothes in the West River, she found a giant stone. From the stone sprung five lizards, who grew into dragons. She raised them tenderly and when her village had drought, the dragons brought rain. When the river threatened to flood, the dragons were there to divert the floodwaters. When she was quite elderly, the Emperor summoned her to the capital. Her dragon sons prevented the arduous journey (which was by river of course). When she passed away in 211 B.C. her dragon sons were devastated and transformed into five human scholars who held her funeral rites and buried her in Jiangwan.

Later, she was elevated in status to a deity, rising to the heavens as an immortal.

Pilgrims consider this eighth day of the fifth lunar month the Dragon Mother’s birthday and observe time-honored rituals. First, they wash their hands in the Dragon Spring to clean off the worldly dirt. The pilgrims then burn incense and present gifts at the temple. They bow, then kneel on the floor, and pray to the goddess. After this devotion, they light off firecrackers to respectfully invite the Dragon Mother to receive their gifts and fulfill their wishes.4

As one scholar notes, “It is not a coincidence that the pilgrimage to the Dragon Mother Temple falls on the eighth day of the fifth lunar month, as the fifth lunar month was the time when the danger of seasonal flooding of the West River (which is commonly known as “xiliao 西 潦,” literally “west flood”) was the most imminent. The West River therefore was both a lifeline and a constant threat to the local people, who felt a real need to appease the river as well as to express their gratitude to the river goddess on this annual festive occasion.”5

The Dragon Mother and other water goddess (“Shuimu”) traditions go back millennia and it’s not hard to see why. The specter of drought, famine, or flooding was constant. Seafaring populations too, had multiple goddesses they sought blessings from for their safe voyage (Dragon Mother, Sea Goddess Mazu, and the shuimu (“Water Goddess”).

In 1861, John Henry Gray observed a ceremony to the Dragon Mother:

“…On a small temporary altar, which had been erected for the occasion, stood three cups containing Chinese wine. Taking in his hands a live fowl, which he continued to hold until he killed it as a sacrifice, the master proceeded in the first place to perform the Kowtow. He then took the cups from the table, one at a time, and, raising each above his head, poured its contents on the deck as a libation. He next cut the throat of the fowl with a sharp knife, taking care to sprinkle that portion of the deck on which he was standing with the blood of the sacrifice. At this stage of the ceremony several pieces of silver paper were presented to him by one of the crew. These were sprinkled with the blood, and then fastened to the door-posts and lintels of the cabin.”6

It wasn’t just sailors and locals to the West river who observed such pilgrimages and prayer rituals. When there was a drought, even government officials were tasked with conducting prayers to the Dragon King.

Failure to Worship the Dragon King, or Worse, Destruction of a Dragon King Temple, Can Lead to Heaven-Sent Disaster!

During the Great Flood of 1931 in Wuhan, one official lamented that the people blamed the flood on the destruction of a Dragon King Temple.7 The Dragon King Temple in Hankou had been demolished in 1930 to make way for a new road, so the timing of the flood was uncanny.

This flood affected 53 million people. The officials of Wuhan had to repent. Several prominent officials of Wuhan participated in rituals designed to placate the Dragon King, including the mayor. They kowtowed to the Dragon King altar, beseeching the deity to spare Wuhan from the flood.

Citizens of the region also blamed officials for outlawing the singing of “spirit operas” traditionally performed to assuage flood dragons.8

To those who worshiped the Dragon King, destroying his temple that sat atop the dyke was clearly a bad idea.

Maybe a River Near You Has a Dragon Deity.

Even if a Dragon King or Dragon Mother temple isn’t available, you can still make a pilgrimage to the rivers. At least forty rivers in China are named for dragons including these rivers in Shanghai: Shanghai: Longquangang He 龍泉港河 (Dragon Spring Port River), Bailonggang He 白龍港河 (White Dragon Port River).9

Just be sure to be properly deferential, and perhaps offer a song to the river dragon.

Julia Vee & Ken Bebelle

We would like to thank Dr. Yasmin Koppen of University Leipzig for her friendship, and generously sharing her expertise and scholarship in East Asian dragons.

Order Ebony Gate Here:

- Chau, Adam Yuet “Mysterious Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China” (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006) 88.

- Fan Lizhu and Chen Na “Resurgence of Indigenous Religion in China” (2013) 11.

- Courtney, Chris “The Dragon King and the 1931 Wuhan Flood: Religious Rumors and Environmental Disasters in Republican China” (University of Cambridge, Twentieth-Century China 40.2, May 2015) p. 88.

- Tan, Weiyun “Dragon mother temple keeps legend alive for 2 millennia” Shine, Nov. 12, 2021 https://www.shine.cn/feature/art-culture/2111128066/

- Poon, Shuk-Wah. "Thriving Under an Anti-Superstition Regime: The Dragon Mother Cult in Yuecheng, Guangdong, During the 1930s." Journal of Chinese Religions 43, no. 1 (2015): 34-58. muse.jhu.edu/article/708611.

- Poon, pg 41.

- Courtney at p. 83.

- Courtney at p. 100.

- Zhao, Qiguang Chinese Mythology in the Context of Hydraulic Society Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 48, No. 2 (1989), pp. 231-246.

- cindyxiong. “Ancient Bronze Dragons Carving in the Ancient Dragon King Temple along Yangtze River,China. Foreign Text Means King. Stock Photo.” Adobe Stock, stock.adobe.com/images/ancient-bronze-dragons-carving-in-the-ancient-dragon-king-temple-along-yangtze-river-china-foreign-text-means-king/100861913?prev_url=detail. Accessed 6 July 2023.