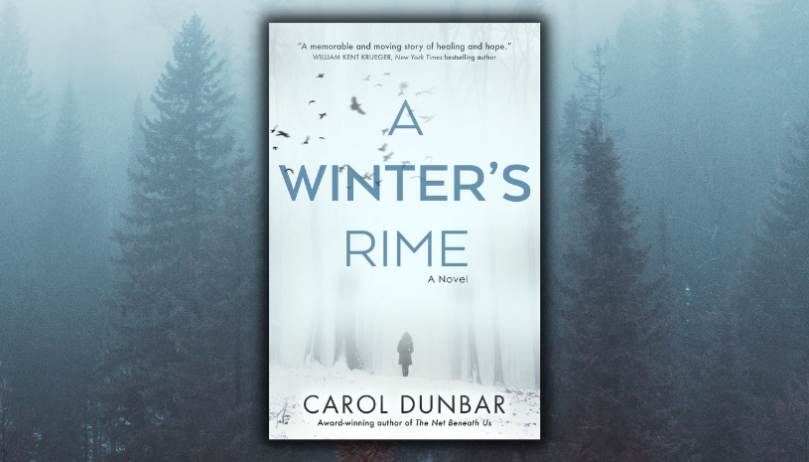

A harrowing and emotional novel set in rural Wisconsin—A Winter’s Rime explores the impact of generational trauma, and one woman’s journey to find peace and healing from the violence of her past.

A harrowing and emotional novel set in rural Wisconsin—A Winter’s Rime explores the impact of generational trauma, and one woman’s journey to find peace and healing from the violence of her past.

Mallory Moe is a twenty-five-year-old veteran Army mechanic, living with her girlfriend, Andrea, and working overnights at a gas station store while figuring out what’s next. Andrea’s off-grid cabin provides a perfect sanctuary for Mallory, a synesthete with a hypersensitivity to sound that can trigger flashbacks from her childhood.

The getaway that’s largely abandoned during the off season starts out idyllic, until Andrea’s once-loving behavior turns controlling and abusive, and Mallory once again finds herself not wanting to go home. After a particularly disturbing altercation, Mallory escapes into the subzero night and stumbles into Shay, a teenage girl, injured and asking for help. But it isn’t long before she realizes that Shay isn’t the only one who needs saving.

A story about sisterhood and second chances, A Winter’s Rime looks to nature to find what it can teach us about bearing hardship and expanding our capacity to forgive—not just others, but ourselves.

Carol Dunbar is the author of the critically acclaimed novels, The Net Beneath Us—winner of the Wisconsin Writers: Edna Ferber Fiction Book Award, and A Winter’s Rime. Read below to see the inspiration behind her upcoming book, finding the voice of her main character, and how she discovered the best way to tell her story!

By Carol Dunbar:

The idea for my second novel dropped into my head whole and perfect like an egg; at its center glowed the yolk of my personal experience with trauma and what I was still trying to understand.

Most of that first draft I wrote by hand in journals: the process felt intimate, confessional, and propulsive. My main character Mallory came through very strong for me. She was ready to tell her story; as a writer, I felt ready to receive it. It was a magical partnership.

Then, we got into an argument about the right way to tell her story.

In her book about the creative process, Big Magic, author Elizabeth Gilbert writes about how ideas swirl around us begging for attention until we agree to take them on and make them manifest. I totally truck with that. I was 30,000 words into an entirely different novel when this story took hold. I knew I had to write it, and I knew I had to write it now.

The plot centers around Mallory Moe, an army veteran returning home after serving overseas, who is going through a quarter-life crisis. She can’t sleep, she’s in a bad relationship, and she hasn’t talked to anyone in her family in four years. To avoid being home she goes on long walks after working overnight shifts at a gas station store. One night, she runs into Shay, a teenage girl who is injured and asking for help. Shay is in even worse shape than Mallory, and in trying to help her, Mallory is finally motivated to confront the violence of her past.

For guidance on how to tell this story, I looked to Elizabeth Strout’s My Name is Lucy Barton. I thought her fiction-as-memoir style would work well for Mallory’s story of healing, and I studied the opening chapters of Lucy Barton, breaking them down beat by beat. I typed out the entire first draft of A Winter’s Rime in first person, using Mallory’s voice. I printed out that draft and put it away for six weeks.

When I went back and read, it didn’t work.

First person was the wrong voice for the story because it was Mallory who was undergoing the transformation. She didn’t yet have the self-awareness for those moments of self-discovery. I needed third person for its distance and ability to navigate and weave the past and present narratives.

My next draft I wrote in third person, and everyone in my writing group was like, “Woah, what did you do? This is so much better.” It worked, but I kept getting these strong nudges from Mallory. Sometimes when writing I would slip into first person, and this was very confusing to me. I thought I had the voice wrong, so I hit the pause button and started experimenting again.

I tested out second-person, using the epistolary style that Ocean Vuong so artfully employed in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. It has this propulsive quality to it—he’s absolutely driven to understand what happened to him and his mother; Mallory is absolutely trying to understand what happened to her. For several weeks I played around with writing the book as a letter from Mallory to Shay, but that also resulted in another failure.

I went to a three-day workshop taught by Diane Wilson, author of The Seed Keeper. I told her about my struggle with how to tell this story, and she suggested I try using a rotating first-person voice. I had used a rotating third-person voice in my first novel, The Net Beneath Us, and I loved being able to view the same event through the eyes of multiple characters. The next morning, I eagerly dove into the exercise that Wilson had taught us.

Using the full name of another main character in my novel, I closed my eyes and said the words, “Noah Quakenbush, tell me your story.” Then I listened, ready to write. And it was really funny because he would not talk to me. I heard nothing but birds chirping from outside. Everybody clammed up, none of my characters would talk, and I got the sense that they were afraid to talk. This was Mallory’s story, and they knew it.

Okay, fine, I thought. I can get on board with that, but as the writer, I needed to find a voice structure that worked for the book.

In No Country for Old Men, Cormac McCarthy used both first and third-person voices. I studied that, then did an entirely new treatment of the novel, using the third-person voice for the main driving action of the story, with italicized first-person passages where the healed Mallory got to talk, sharing her insights. When my agent read it, she didn’t like those italicized passages. None of my readers did—they got in the way of the plot’s momentum, and messy Mallory was way more interesting.

It felt to me like I was in a wrestling match with my main character and I didn’t know how to make both of us happy.

At an author event with Elizabeth Strout, I asked her how she knew that first-person was the right voice for her Lucy Barton novels. She told me, “Voice is the golden thread that I follow when writing. I trust it implicitly.” Those words gave me the balls to press on and trust my crazy process.

What I found was the monologue. Instead of recounting what happened to Mallory as a backstory scene, I used first-person monologues in present-action scenes, where Mallory is finally able to tell her story for the first time. She can only do this once she meets Shay, and that makes their scenes so much more powerful. It was very moving to me, to hear a survivor talk after years of not being able to talk.

Finally, Mallory and I were in agreement.

I’m really glad I trusted my instincts and kept searching for the right way to tell this story. I do believe there is something to Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic, that as writers we are “neither slave to inspiration nor its masters, but something far more interesting—its partner.”

Click below to pre-order A Winter’s Rime, available 9.12.23!