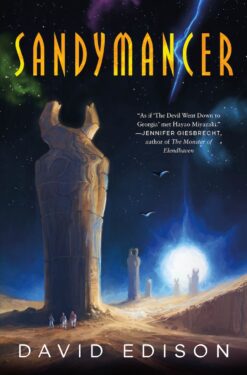

Writers spend a lot of time alone in their own heads. David Edison is here to talk about the sometimes loneliness of writing, finding his community, and his new book, Sandymancer.

Check it out!

There’s a true myth that writers are solitary animals, and that our work takes place in some holy half-light of focus and flow. That’s bupkis.

Pick a writer—any writer! Now imagine them working. Is the scene cozy, or is it a busy one? Is there a cat on a shoulder, a dog in a lap? Tea, coffee, Mommy’s perfume scotch? Is there smoke from cigarettes, incense, or a fireplace? Are they in a room of their own?

Are they alone in that room?

Writing and dreaming can both be lonely work. But unlike writing, there’s no workshop I know of that teaches you how to curate your dreams, or warns of the hungry quicksand that may swallow you whole if, by chance against chance, your dream comes true and you find yourself without a new dream to chase. That’s a lesson I learned after the fact, almost backward.

But almost everything that’s happened to me has happened backward, starting with gastrulation, when I was a 21 day-old embryo, and the cells that would become my organs failed to properly rotate, leaving me with mirror-imaged, inverted organs. The inversion is imperfect—when I was ten, they disemboweled me to find my appendix.

I felt very alone in that cold, yellow-white room with its one blue blanket. Was I?

When, by hook and by crook, I hustled my way into an informational interview with the legendary editor-cum-agent Loretta Barrett, I had no idea that my career would begin as backward as my zygote did. This woman had hired Jackie Onassis to work at Doubleday, and now she wanted to read “the longest thing I had.” That was the first three chapters of The Waking Engine, which I had shelved in 2003 because I thought it too baroque and unwieldy.

“Finish the book and I’ll sell it.” Loretta disagreed, and who was I to argue? So I did, and she sold it to my dream publisher, the one whose craggy mount I had looked for on book spines since I was eight.

Hoo doggies, did I feel alone. Electric! Alive! Alone.

I never expected I’d need a new dream. Finishing a book, finding an agent, and selling that book to Tor seemed like a reasonably unattainable dream—I don’t fault myself for failing to plan ahead. I learned abruptly that whether our dream comes true or if it crashes like one of those scary race cars, what follows is exactly the same: something new that’s up to you.

My advice? Don’t just dream big—dream thoroughly. Dream with multiplicity. They’re dreams, so there’s no sense in limiting them. If I had allowed myself to look farther down that dream-road, I might have saved myself many headaches and at least one existential crisis.

More backwardness: It was only after Waking Engine was in revisions that I began to find a community of writers. I feared mere contact with other writers would destroy my confidence. Backward! With community came mentorship, and at the sage advice of Delia Sherman, I applied for the Clarion West Writers’ Workshop. Delia aptly pointed out that in my backwardness, I had skipped some basic “boot camp” elements of my writer’s education. I’d been in workshops since I was 15, but never at a professional level. My concept of POV, for instance, was woefully underdeveloped, and it’s only because of Delia’s one-on-one instruction that Waking’s sprawling, multiple POV characters weave together with any sense at all.

For the first time in my writing life, I didn’t feel quite so alone.

Clarion West changed me on a mitochondrial level.I don’t mean that it changed what I write, or even how I write—it’s hard to convey how intense those six weeks can be. It scraped out much stagnant bullshit and poured in distilled, peer-reviewed craftsmanship. I needed a few years afterward, to let that ultra-concentrated experience percolate through my subconscious.

I came out knowing what I needed to learn next. I was proud of Waking‘s complexity, but if I needed to learn anything, it was simplicity. So I set out to write a more simply-plotted story with a single POV character and a single narrative arc. (There is a minor second POV character, because I am a recovering abuser of embedded texts.)

I was not alone. Loretta passed away too early, my editor left Tor, and time passed as I wrestled with the choice to reboot my career—but for the first time, I had found My People.

That first day at Clarion West revealed the true treasure I would find there: community. Here were 18 people who had been the rockstar of every workshop they’d ever taken, and we instantly realized that we were in the company of…ourselves. We were the same Cylon model, under the skin, each of us nervously and beautifully embodying the writer’s core programming, which Octavia E. Butler so perfectly summarized: “an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive.”

Suddenly I could share in Usman T. Malik’s passion, which would win him well-earned awards. I could share in E. Lily Yu’s switchblade-sharp deconstructions, in Neon Yang’s joy and off-the-cuff, from-memory piano recitals. Jen Geisbrecht’s punchy snark and absurdly brilliant sentence structure. Malcom Devlin’s one-liners and haunting horror stories. Alix Solano’s laughter and siblingship. Helena Bell’s three-theme theory of storytelling, and her encyclopedic knowledge of where to submit your stories. Kelly Sandoval’s beautifully sweet soul that she reflects so perfectly in her writing. I’ll stop there, but you get the picture: it was a good time, and I’ve felt like a proud brother, watching my cohort earn and receive their accolades.

The lesson of community reverberates. During the final work on Sandymancer, I reveled in the collaboration between my editor, the cover and map artists, design, marketing: Claire Eddy; Sanaa Ali-Virani; Andreas Rocha, Rhys Davies; Julia Bergen; my local photographer, Blanca Parsiak, and more—all of these people and more were right there with me. They’ve told the story of Sandymancer with their insight, expertise, and artistry.

As for me? My crisis came and went. I wrote the novel that I needed to write, Sandymancer, and I learned the lessons that I set out to learn. Not one to repeat mistakes, I wrote the sequel with new lessons in mind. Will the risk be worth it? Will readers find it?

I’ll find out. When I do, I may be isolated in a room of my own, but I will not be—and never was—alone.

by David Edison

David Edison was born in Saint Louis, Missouri. He currently divides his time between New York City and San Francisco. In other lives, he has worked in many flavors of journalism and is editor of the LGBTQ video game news site GayGamer.net.

…And he sleeps in unicorn corpses, tauntaun style.

Order Sandymancer Here!