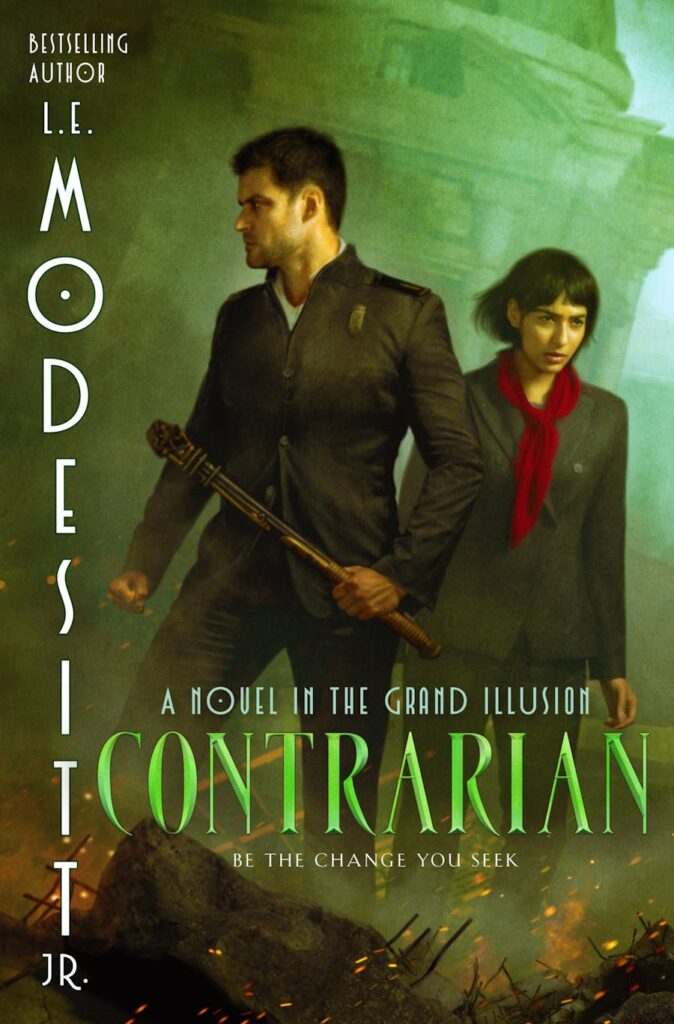

L. E. Modesitt, Jr., bestselling author of Saga of Recluce and the Imager Portfolio, continues his gaslamp political fantasy series which began with Isolate and Councilor. Welcome to the Grand Illusion

In Contrarian, protests against unemployment and poor harvests have become armed riots as the people sink deeper into poverty. They look to a government struggling to emerge from corruption and conspiracy.

Recently elected to the Council of Sixty-Six, Steffan Dekkard is the first Councilor who is an Isolate, a man invulnerable to the emotional manipulations and emotional surveillance of empaths—but not the recent bombing of the Council Office Building by insurrectionists.

His patron, the Premier of the Council, has been assassinated, leaving Dekkard with little first-hand political experience and few political allies.

Not only must Dekkard handle political infighting, and continued assassination attempts, but it appears that someone high up in the government and corporations has supplied arms and explosives to insurrectionists.

Insurrectionists who have succeeded in taking over a naval cruiser that no one can seem to find.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of Contrarian by L. E. Modesitt, Jr., on sale 8/15/23

Chapter 1

Duadi

32 Winterfirst 1267

Dekkard glanced out the carriage window at the ironway station platform, the predawn darkness only dimly lit by the tall gas lamps, then back toward the slender but trimly muscular black-haired woman sitting beside him on the dark blue velvet seat. “Well, Ritten Ysella-Dekkard, how does it feel to embark on the next major event of our life?”

“We’ve had enough major events already, dear,” she replied in the slightly sweet tone that suggested he was edging toward a spoutstorm.

“Buying a house together in Gaarlak will be a major domestic event,” he replied in a tone he hoped was conciliatory, “not a catastrophic one like the shelling of the Council Office Building.” And the assassination of the Premier. The man who had given him the chance to become a councilor— and to meet Avraal. If only . . . but who could have foreseen the method of the Meritorist attack?

Avraal shook her head. “I’d never thought we’d end up where we are.”

“I certainly never expected to be a councilor, or to be married to an empath who’s descended from ancient royalty,” Dekkard replied wryly.

“Everyone’s forgotten about the kings of Aloor . . . except my father and brother.”

The first-class steward, wearing a deep blue uniform trimmed with silver piping, strode down the center corridor, saying, “The express will be leaving immediately.”

Less than a minute later, a steam whistle sounded, and with a slight jolt, the carriage began to move.

Since there was little to see through the wide window, at least not clearly, Dekkard studied, as best he could in the dim light, the wooden paneling, a dark stained cherry, rather than the yellow cedar, or even the older black walnut. “I think the paneling in this carriage is the new cherry, most likely from dowry lands Jareem Saarh sold to Guldoran Ironway.”

“He’ll end up losing everything in the long run, and I wouldn’t care in the slightest, except that it wouldn’t be fair to Maelle.”

“At the Yearend Ball, he did say that she was likely running the lands better than he could.”

“He believed it. I could sense that,” replied Avraal. “For her sake, I hope he was right . . . but he’s been wrong about more than a few things, like getting together with Palafaux and Schmidtz.”

“Exactly, and I have the feeling that that trio has something else planned.”

“No doubt connected to Ulrich and Siincleer Shipbuilding. Speaking of those two . . . do you think Ulrich might have been the one behind that story in the Tribune?”

“Our most honorable former premier, who likely ordered the assassination of his devoted former aide to keep anyone from tying corporacion aid to the New Meritorists? How could you possibly believe that?” Dekkard’s voice dripped with sardonicism.

“I don’t feel that sorry for Jaime Minz, not after the times he tried to get others to kill you, and his funneling explosives to the New Meritorists. But still . . . he did all of Ulrich’s dirty work, and Ulrich or one of his cronies just disposed of him like that, and no one’s even looking at Ulrich.”

“Guard Captain Trujillo is, but there’s no hard evidence,” Dekkard pointed out. “Just like with Lamarr’s and Decaro’s deaths. I still wonder about how much Jens Seigryn was involved with Decaro’s death.” Thinking of the Craft Party political coordinator for the Gaarlak district, Dekkard couldn’t help but shake his head. “I wasn’t the one who schemed to make me councilor instead of him. That was Gretna Haarl, and I didn’t even know about it. Jens had to know that.”

“I’m not sure that will make him any happier. I don’t like it that you had to use him to organize tomorrow’s breakfast meeting with all the guildmeisters.”

“What else could we do? We don’t have much choice, not with so little time, especially since he’s the Advisory Committee’s representative in Gaarlak, in addition to being the Craft Party coordinator.”

“I still wish there had been another way, without involving him.” Avraal frowned. “I’ll be carrying my knives, and so will you.”

“All the time now. I did bring my personal truncheon, in case it appears necessary.” He smiled wryly. “It may be that the safest place I’ll be is at Plainfields on Findi afternoon.”

“It was kind of Emilio and Patriana to invite us for an early dinner.”

“I suspect he wants to hear about the Landor councilors we both know. Patriana may not miss his being a councilor, but I suspect he does at times.”

After a short silence, Avraal said, “How do you think Nincya and Emrelda will get along?”

“Without us there, you mean? They’ll do fine. Nincya respects your sister, and she’s enough of an empath that she can sense if something’s troubling Emrelda, and Emrelda’s direct without being overbearing. If you want to worry about something, worry about whether we can find a decent house in the right place.” Dekkard shook his head. “I just hope that the property legalist that Namoor Desharra recommended understands our particular situation.”

“Our limitations, you mean?”

“I know your parents gave you that personal bond, but . . .” I don’t want you using it all, even if we do have to buy something in Gaarlak because I’m a councilor.

“Stop feeling guilty. Part of the reason they sent it was because I married a man whom they could brag about, rather than avoid talking about.”

“As in,” Dekkard continued in an archly haughty tone, imitating an arrogant Landor, “‘Avraal did marry a councilor of the Sixty-Six, not quite the same as a Landor heir, but given that she’s an empath, she did quite well’?”

Avraal tried . . . and failed . . . to hide a sardonically amused smile. “You did that rather well . . . almost like Cliven.”

Dekkard winced.

Avraal laughed, then leaned over and kissed his cheek.

━━ ˖°˖ ☾☆☽ ˖°˖ ━━━━━━━

Chapter 2

Just before the first morning bell, Dekkard and Avraal left their second-floor room at the Ritter’s Inn and started down the wide staircase, the heavy maroon carpeting on the steps muffling the sound of their boots.

Dekkard hadn’t slept well after waking up in the middle of the night from another nightmare about the shelling of the Council Office Building. At least the nightmares are getting less frequent. With that thought, he looked out over the lobby, but didn’t yet see Jens Seigryn.

For the coming breakfast meeting, Dekkard wore one of his gray winter suits with the red cravat unofficially suggesting a councilor, while Avraal wore a conservative dark blue suit with trousers and a light blue head-scarf, draped over her shoulders. She also wore a golden lapel pin with a small red stone in the center, a quiet but necessary statement that she was a certified security empath.

Dekkard couldn’t help noticing that the brass lighting fixtures on the wall didn’t seem quite as well-polished as when they had stayed at the inn the previous summer. He also hoped he could put the names he’d studied to the faces of the guildmeisters he and Avraal would shortly encounter, since they’d only met several briefly.

From the staircase, the two walked across the smooth dark gray slate floor, past the small restaurant, already more than half full, toward the private dining room.

Jens Seigryn—short and wiry, with thinning brown hair and a high forehead—waited beside the open door. As he caught sight of the couple, he smiled broadly.

“Steffan, Avraal . . . or should I say Councilor and Ritten?”

“Steffan and Avraal is fine, Jens,” said Dekkard cheerfully. “I appreciate your arranging the breakfast for us, especially on such short notice.”

“That’s what political coordinators do. Everyone wanted to come, and that’s unusual.” Seigryn paused. “Gretna Haarl . . . insisted . . .”

“That she wanted to be seated next to me . . . or Avraal?”

Seigryn looked surprised at Dekkard’s last words. “Avraal . . . you really thought she might want to be next to Avraal?”

“It was a definite possibility. When she wrote to congratulate me, she only had two questions. When was I coming to Gaarlak and was I smart enough to listen to Avraal.” That wasn’t how Haarl had written it, but it was definitely what she’d meant. Then Dekkard looked directly at Seigryn. “I trust you know that I had no idea what Gretna had in mind.”

Seigryn smiled ruefully. “I knew that from the moment she became guildmeister she wouldn’t support anyone either Axel or I proposed. You were the only one of those she proposed that anyone else would accept.” After a moment, he went on, his voice both subdued and slightly cautious.

“Later, when you have a moment, could we talk . . . about Axel?”

“We’d be more than happy to. He always spoke well of you.”

“Thank you.” After a momentary hesitation, Seigryn said, “We’d better go in . . . several of the guildmeisters are already here.”

“Including Gretna?” asked Avraal.

“She was the first.”

Seigryn led the way into the private dining room, just an oblong chamber some eight yards long and six wide. Dark oak paneled the walls below the chair rail, with cream plaster walls above the rail. The maroon carpeting was the same as that on the main stairs, and the crown molding matched the carpet.

Three people stood beside the large round table, set with silver cutlery and a plain white linen cloth. Dekkard immediately picked out the thin, almost frail figure of Gretna Haarl, and the stocky Yorik Haansel of the Stonemasons, but had to mentally struggle a moment to place the other woman before finally coming up with the name of Arleena Desenns, the head of the Weavers Guild.

“Councilor and Ritten Dekkard were a bit early,” announced Seigryn. “We’ll wait a few more minutes before we sit down, but I thought you’d all like a few words.”

Dekkard immediately went to Gretna Haarl, smiled, and said, “I got here at the first opportunity, and, as I wrote you, I’d already taken your counsel in not letting go of Avraal.”

“You’ve been a most pleasant surprise as a councilor, Steffan,” replied Haarl. “You pushed through Security reforms. Myram Plassar tells me you’re pushing reforms for working women.”

“We’re also working on broader pay reform legislation. That might take longer.” Dekkard regretted that Plassar couldn’t have been at the breakfast, but since she was only a regional steward and not a guildmeister, her inclusion would have raised the hackles of the other regional stewards, and including everyone would have made the breakfast too large . . . and too costly for his expense account.

“That’s good to hear.” Haarl looked to Avraal. “How much of that was your idea?”

Avraal smiled. “Steffan came up with it all.”

“Not that she hasn’t been encouraging . . . and kept me from making certain mistakes,” added Dekkard.

“Amazing . . . a man with initiative who also listens.”

“It happens occasionally.” Dekkard gave a slight chuckle, then sobered. “Premier Obreduur did both.”

“Look where it got him,” interjected Yorik Haansel, who then smiled at Dekkard and added, “It’s good to see you here, Councilor.”

“As I said, I came as soon as it was possible.”

“The newssheets said that the Meritorists destroyed your office. How did you escape and Premier Obreduur didn’t?” asked Haansel. “There was some question . . .”

Dekkard managed to maintain a pleasant expression, despite his dismay at the possibility that the Tribune story had reached Gaarlak. “They fired at his office first and at mine last. When I heard and saw the first explosion I got my staff out of the office and into the stone-walled stairwell. The attack didn’t last more than ten minutes.”

“Why did they stop that soon?” asked Haarl.

“Either their makeshift steam cannon or one of their handmade shells exploded as they fired, and that destroyed the cannon, any remaining explosives, and them. Otherwise, it could have been much, much worse.” Dekkard saw two more guildmeisters arrive—Alastan Cleese, of the Farmworkers, and Charlana Boetcher, who had replaced Johan Lamarr as guildmeister of the Crafters.

Jens Seigryn closed the door to the private dining room and walked toward the table. Then he stopped and said, “If you’d find your seats . . . we’ll have the blessing.” Seigryn nodded to Dekkard. “Councilor . . .”

From his time visiting and campaigning with Obreduur, Dekkard knew that the Trinitarian faith was stronger in smaller cities, and that a blessing before a meal was expected. He found the card bearing his name and stood behind the chair while the others sorted themselves out. He did notice that Avraal was across the table from him flanked by Gretna Haarl and Arleena Desenns, while Charlana Boetcher stood on his right and Alastan Cleese on his left.

Dekkard bowed his head slightly, then began. “Almighty and Trinity of Love, Power, and Mercy, in this time of trial and upheaval, we thank you for the solidity you bring to this world. We humbly ask that you grant us the wisdom to see illusions for what they are and to understand that all material goods are fleeting vanities, and that the greatest vanity of all is to seek and hoard power, rather than to share it in doing good. We humbly ask you to bless this gathering and the food we will partake, in the name of the Three in One.”

“The Three in One,” murmured those around the table.

“Good short blessing,” declared Yorik Haansel to no one in particular, as he sat down between Boetcher and Desenns.

Immediately, servers appeared and poured café for everyone, then provided two platters of croissants, and one with ham strips.

“Councilor,” began Cleese, as soon as everyone had served themselves, his tone of voice almost apologetic, “I’m sure you’ve followed the weather . . .”

“It’s been terrible all across Guldor. I’ve been worried about the impact on farmworkers and what will happen to food prices.”

“You say that so easily . . .”

“I’m not casual about it. There have been at least four large disturbances in Machtarn in recent weeks over food prices. One ended in such violence that an entire block burned to the ground, and a score of people died. Girls are selling themselves on the streets in poor neighborhoods to earn marks for food. That doesn’t count events in other cities across Guldor. I imagine similar problems have happened in Gaarlak. That’s one reason we’re here. I need to know what I don’t see and the newssheets don’t cover.”

“You were elected two months ago.”

“Alastan,” said Desenns, “stop being a complete idiot. The councilor is new. Despite that, he did manage to pass reforms to get rid of the Security Ministry. Last year you were complaining about that. Don’t you read the newssheets? He’s been the target of the New Meritorists and the Commercers. His office was destroyed. The Council has been in session the whole time since he was elected. What exactly do you expect?”

“We’ve still got problems here, Arleena. Close to a quarter of my farmworkers don’t have enough marks to feed their families right now.”

“That’s the sort of thing I need to know,” Dekkard said quietly. “I personally read every single letter and petition, but no one has yet written me and told me what you just said. I want to find someone I can put on my staff here in Gaarlak, someone that you can talk to so that I’ll learn about issues sooner.”

“If you do that,” said Desenns, “it’ll be the first time in my life.”

“Sounds like a good idea,” boomed out Haansel. “Why didn’t Raathan do that?”

“I don’t know,” replied Dekkard. “Perhaps he relied on his family.”

“Exactly,” declared Cleese. “All he heard about was Landor problems. Nothing about farmworkers, crafters, millworkers . . . the ones who need to be heard.”

“Don’t forget about the artisans,” said Charlana Boetcher, her voice almost acid.

“You artisans have it easy. You’re not out in the weather all the time.”

“Do we have it easy, Councilor?” asked Boetcher sweetly.

Dekkard was beginning to wish that Jon Eliver, the Farmworkers assistant guildmeister, whom he’d met during his previous visit, had come in place of Cleese, but he replied pleasantly, “The five years I spent as a plasterer’s apprentice were the hardest of my life. Artisans don’t have it easy, but most people who work with their hands and bodies don’t. I’ve never forgotten that.”

“You did that? Nobody told me,” declared Cleese defensively.

Boetcher sighed loudly. “I was there when Jon Eliver told you that. So was Gretna Haarl. That’s why we all wanted Steffan as councilor.”

“I heard it, too,” declared Gretna Haarl loudly.

Cleese looked as if he might dispute it, when Yorik Haansel grinned and said, “Give it up, Alastan. My ears are bad, and I heard it.”

Cleese closed his mouth and shook his head.

For a moment, there was silence, and Dekkard let it draw out for a moment, then said, quietly but firmly, “Both Avraal and I do understand. She understands, partly because she’s an empath and partly because she worked her way up, starting in the prisons as a parole screener.” He paused to let that sink in. “We don’t know all that you and the hardworking people you represent have gone through, and the Council has to do better. I’ll do the best I can. For too long the Council has listened only to corporacion and Landor needs and problems, but the current Council has already made a good start in changing that. To keep that momentum, we need to know specific problems and needs that the Council can address. The Council can’t change the weather, but we can look into and seek change in work practices or freight rates . . . or in safety rules. You know where your problems are. So let me know. But remember, we can’t fix everything at once, just like you can’t craft a desk overnight, or get in a harvest in a few bells.”

“If there even is a harvest,” replied Cleese. “More failed this year than in past years.”

For a moment, Dekkard didn’t know what to say that wouldn’t sound flippant or uncaring, but he finally managed to say, “It’s been a hard year everywhere for growers.”

“The Commercers don’t make it easier,” said Haarl. “Premier Obreduur’s wife won a legal action against Gaarlak Mills. They have to pay women as much as the men for the same jobs, but Lakaan Mills still won’t do it. Their legalists file motion after motion, and each motion costs the guild hundreds of marks.”

Dekkard nodded, then said, “Ritten Obreduur told me that mill owners and others would force legal action for every mill corporacion until and unless the Council made the law specifically adhere to the ruling of the High Justiciary. I’m already working on legislation that will do that, but it’s likely to take a while to get such a law through the Council.”

“There are real problems in the Lakaan Brickworks. Others, too, I’d wager,” declared Haansel. “They’ve got new steam driers, and it’s giving the setters consumption . . . leastwise they call it consumption . . .”

After that, it seemed to Dekkard that every guildmeister had a problem or two, sometimes three, but he listened carefully, then responded, ending with a polite request that they send him a letter with as many details as they could.

By the time Dekkard had heard them all out, it was close to third bell, and he was just grateful that there weren’t any frowns or scowls . . . at least, not that he had seen. He just hoped that Avraal had sensed anyone unhappy so that he could follow up with them, although he also hoped that wouldn’t be necessary.

Dekkard then immediately turned to Alastan Cleese. “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize just how bad . . .”

Cleese shook his head. “Not your fault. You’re a fair-minded young fellow trying to do your best . . . unlike some.”

“I am concerned about farmworkers and those who work with their hands. The rest of the winter is going to be hard. I’ll do what I can to improve working conditions, but, as I said earlier, if you have any other specific ideas about what would help, especially on a permanent basis, I’d like to hear from you.”

“Let me think about it. You’ll hear when I have.” Cleese stood.

So did Dekkard, as he said, “Thank you.” Then he turned to Charlana Boetcher as soon as Cleese moved away.

She rose from the table.

Dekkard inclined his head and said, “I trust you won’t mind if I visit some of the crafters’ shops and businesses over the next week.”

“I’d hoped you would.” She smiled and handed him a card. “Come by if you have any questions.”

“Thank you.” Before slipping the card into his suit pocket, Dekkard took a quick look at the name on the card—Boetcher Silver. “Is there any place or area you’d recommend where I might start . . . in addition to yours, of course?”

“It doesn’t really matter where you start, just so long as it’s not with us and that you visit several areas so that people won’t get the impression that you just made a few token appearances.”

“What you’re suggesting, I think,” Dekkard replied wryly, “is that token appearances might be worse than no appearances.”

“I didn’t say that,” Boetcher replied with an amused smile, “but I didn’t have to.”

After Boetcher stepped away, Gretna Haarl appeared. “I had a very good talk with Avraal. Keep listening to her.”

“I’ve never stopped listening to her, and I don’t intend to now.” Especially now.

“Excellent. I look forward to seeing you on Furdi.” “Avraal has the details?”

“She does.” Haarl smiled. “You do well in difficult situations. Until Furdi.”

Dekkard thought she seemed satisfied as she left, although he wondered just what Avraal had committed them to.

Yorik Haansel was the last to come up to Dekkard. “Glad to see you talked to Alastan before he left. I’ll talk to him, too. He’s a good man. He just doesn’t like to admit that his ears aren’t what they used to be.” He paused, then said, “Guldor lost a great man when those idiots killed Axel.”

Dekkard lowered his voice and said, “They weren’t idiots; they were corporacion tools out to weaken the Council. Part of that was already proved, but there isn’t evidence to go further.”

Haansel nodded slowly. “Doesn’t surprise me. Seemed unlikely that Meritorists would do that by themselves. You just be careful.” He smiled. “It was a good breakfast.” Then he turned and headed for the door.

In moments, Dekkard and Avraal were alone in the room with Jens Seigryn.

“You sounded like Obreduur . . . a younger Obreduur,” said Seigryn.

“Who do you think I learned it from?” Dekkard paused. “They certainly had a lot of pointed questions.”

“This is the first time in more than a century that guildmeisters here in Gaarlak have a chance to question their own councilor in person. The Landor councilors avoided meeting with them like this.”

“Jens,” said Dekkard, “you wanted to talk about Axel . . .”

For just an instant, Seigryn looked surprised, as if he hadn’t expected Dekkard to bring up Obreduur. “How did it really happen? He was always so careful.”

“The New Meritorists had help building a steam cannon and makeshift shells. Then they hid it inside a canvas-topped stake lorry, drove it down the service road behind the Council Office Building, stopped, and targeted his office from about fifty yards. In less than a sixth they took out five offices. The Justiciary Ministry and the head of the Council Guards suspect the help and expertise came from corporacions, but there was no hard evidence. They captured one low-level corporate officer, and he was immediately assassinated. Officially, it was all his doing.”

“The bastards . . . Axel was the best chance they had of a better life.”

“The Meritorist leaders are fanatics, and the corporate types are very good at manipulation,” replied Dekkard. “You’ve seen more than a little of that.”

“Landors . . . Commercers . . . they’ll never change.”

Dekkard smiled. “Then . . . I guess it’s up to us Crafters.” He paused, then said, “Thank you for arranging the breakfast. We appreciate it.”

“You’re welcome. You paid for it,” said Seigryn with a touch of humor. “Now . . . if you need anything else . . .”

“We’ll let you know. This is just a low-key visit. We need to get more familiar with Gaarlak and look into the possibilities of fashioning a ‘permanent tie to the district’ . . . as the Great Charter phrases it.” Dekkard inclined his head. “Thank you, again. We’ll walk out with you.” He gestured toward the door.

“What are your plans?” asked Seigryn as he walked beside Dekkard.

“First, to sign for a steamer, and then we’ll see. We have some exploring to do.” Dekkard turned and looked to Avraal. “Shall we go?”

Once they saw Seigryn off at the inn’s lobby doors, Dekkard looked to Avraal. “How bad was the damage?”

“From what I sensed, you contained it all.”

“With your help.”

“Jens definitely tried to set you up,” said Avraal quietly. “He must have suggested that they all bring their problems . . . saying something like now that they had a Crafter councilor they should let you know what really needed to be done. Gretna also didn’t request to be seated by me.”

“You sorted that out, I take it.”

Avraal smiled. “We sorted it out. She seemed irritated. So I just asked her if she had any questions for me because Jens had indicated that she wanted to be seated near me. She managed not to explode. After a long moment, she asked if he’d really said that. I told her exactly what you said and Jens’s reply.”

“And?”

“She asked that neither of us do anything unless we heard from her. Right now, it’s probably better that she handles it.”

“I don’t think this is going to turn out well for Jens,” said Dekkard.

“He’s having trouble realizing that Guldor’s changing. That’s another reason why he shouldn’t have been councilor. I promised that you’d show up at Gaarlak Mills, outside the larger building, at fourth bell on Furdi, to meet any millworkers who wanted to see you. After that, Arleena Desenns, Gretna, and I decided that you should do the same thing on Unadi afternoon outside the buildings at Lakaan Mills. Arleena said she’d come up with a banner and have it at Gaarlak Mills tomorrow afternoon.”

“That was kind and helpful of her.”

“She knows that you’re the only kind of Crafter who can hold the Gaarlak district, and that otherwise it would go to the Commercers.”

“I can see that. In the last election, the Commercer candidate, Wheiter, had twice the votes of the Landor candidate, and was less than two thousand votes behind Decaro.” Dekkard paused, then said, “I committed to Charlana that we’d visit craft establishments all around the city while we’re here.”

“Good.”

“How was Alastan Cleese feeling when he left? I tried to smooth that over, and Yorik Haansel said he’d talk to Cleese.”

“He was mainly feeling a little embarrassed when he left.”

“We should find him and drop by in a day or so, or maybe on Findi.” “Findi,” said Avraal. “I already got his home address from Arleena.” “Thank you. It’s going to take both of us to do my job . . . but then, you already knew that.”

“I did.” She smiled warmly. “But it’s nice to hear you say it.”

“I’ll finish the paperwork for the steamer, and we need to go see Namoor.”

“I’ll get our overcoats from the room while you’re doing that.” She paused. “Do you have your cards with you, or do I need to get them?”

“I remembered them, but thank you.”

As Avraal headed for the staircase, Dekkard went to the lobby desk, where he signed for the small Gresynt steamer that he had arranged for, knowing that he and Avraal needed to become more familiar with the city, and they couldn’t do that by being driven around. Having a steamer would allow for much more flexibility, given all that they needed to do in the limited time they had.

“The steamer’s out front, sir,” said the concierge as he handed over the keys. “It’s the dark blue one.”

“Thank you.” Then Dekkard turned to join Avraal near the foot of the staircase, where he donned his overcoat and Avraal eased the headscarf over her hair, before the two walked out to the Gresynt. It was much like Emrelda’s model, but the dark blue paint was more subdued than Emrelda’s brilliant teal.

In minutes, Dekkard headed east just past the center square, and its imposing marble statue of Laureous the Great, before turning north through the few blocks containing banques and office buildings. Most of the façades of the three and four-story buildings looked tired, worn, and grimy. Shortly, he turned left, driving through the North Quarter’s grand houses, some of which had definitely seen better days. He tried to remember the route to the more modest dwelling that had been converted to hold the legal offices of Namoor Desharra. Three turns later—one of them wrong, necessitating the other two—Dekkard brought the Gresynt to a stop in front of the three-story, brownish brick dwelling on West Oak Street with the small sign in front reading desharra & associates.

“That wasn’t too bad from memory.” Dekkard grinned ruefully, then got out, closed his door, and walked around to open the steamer door on Avraal’s side.

They walked up three steps and then another five yards to the door. Dekkard was about to try the bellpull when Avraal pointed to a small sign.

IF THE DOOR IS UNLOCKED, PLEASE ENTER.

Dekkard tried the door. It was unlocked. He opened it and motioned for Avraal to precede him.

Before either of them had taken three steps into the foyer, which had a closed door on the right and one on the left that stood open to an empty sitting room, the gray-haired Namoor Desharra appeared and walked through the sitting room toward them.

“Councilor and Ritten Dekkard, you’re a bit earlier than I expected. Jens said it might be after fourth bell.”

Her words reminded Dekkard that part of Desharra’s legal practice was as the legalist for the Craft Party of Gaarlak. He smiled. “Lately, Jens has been a bit confused, at least where we’ve been concerned. I wouldn’t be surprised if that continued.”

“You did know that he wanted to be councilor?”

“Not until after I’d been sworn in. I could tell that Axel was stunned that I’d been recommended by the Gaarlak Craft Party.”

“I understand that acrimonious would not have been an inappropriate description for the selection meeting, although that might even have understated feelings.” Desharra smiled warmly. “It’s good that you’re here.” She motioned to the sitting room. “We have some time before Kelliera Heimdell will be here.”

“She’s the legalist property agent?” asked Dekkard.

“She’s very good . . . and trustworthy.” Desharra settled into the armchair facing the dark blue couch.

Dekkard and Avraal took the couch, and Avraal eased the scarf off her hair.

“Before we get to that,” Dekkard began, “Gretna Haarl mentioned the legal difficulty with getting Lakaan Mills to comply with the terms the High Justiciary imposed on Gaarlak Mills. Ingrella had mentioned that legal action against each mill corporacion might be necessary . . . unless the Council acted to legislate that change.”

“They’ll try to litigate that as well.” Desharra smiled sardonically.

“Sometime during this session of the Council, I’d thought I’d try to introduce legislation to cut any stalling short. Do you have any suggestions that would reduce the scope of litigation?”

“I like the way you said that, Councilor.”

“Steffan . . . please.”

“I could send you the language of our brief and the language of the High Justiciary affirming the lower justiciary ruling.”

“My legalists would find that incredibly useful, especially since much of their earlier work went up in smoke . . . literally.”

“Ingrella wrote me that your office was one of those destroyed. She thinks highly of you, by the way.”

“I think incredibly highly of her.”

“I’m glad you do. You should.”

“I know I’ve imposed on you, but I’d like your thoughts on another matter.” Dekkard leaned forward. “I really need someone here in Gaarlak whom people can contact and who can relay information and concerns to me. Previous councilors relied on family, I suspect.”

“If they even bothered.” Desharra’s lips curled in contempt.

“I don’t have inherited wealth, and neither does Avraal. That means any pay for an assistant, an office, and any expenses have to come out of my office account, and it’s not exactly capacious.”

Desharra frowned for a moment. “We might be able to help. You could sublet from us. There’s a tiny room on the other side of the foyer. We’ve used it as a storage area, but anyone coming would have direct access.”

“So they wouldn’t be going through your space.”

“Exactly. Let me talk to the others, and we’ll see what would cover the expense. Much as I’d like to, under the law we can’t donate it, even for the official business of a councilor.”

“I can see that . . . and if you know of any young legalists who might like a low-paying position . . .”

Desharra laughed. “That will be the least of your problems. Entry-level legalist or legal clerk positions are hard to come by. Some, if it were legal, would pay you.”

“I need someone honest enough to tell me what is actually happening, whether they think I want to hear it or not.”

“I can think of several possibilities, and you can talk to them later this week.”

“Both of us will talk to them,” said Dekkard. “I thought as much,” replied the legalist.

“Do you have an address where I could reach Myram Plassar? Her contact information vanished in the attack on the office.”

“She mentioned you were looking into expanding the rights to a legalist for working women who weren’t eligible to join the guild. She has a small office west of the central square, on Goldenwood Avenue, as I recall. I’ll get the exact address while you talk to Kelliera.”

The three discussed setting up the office for another third, when a red-haired woman in a gray overcoat walked through the front door, wearing a matching gray headscarf.

“Kelliera . . . come meet the Councilor and Ritten Ysella-Dekkard.”

Dekkard immediately stood as the property legalist entered the sitting room, realizing as he did that Kelliera Heimdell was even shorter than Avraal.

At that point Avraal and Desharra stood as well, and the legalist said, “I’ll leave you in Kelli’s very capable hands. I’ll have the documents ready for your office by tomorrow afternoon, and I’m here most of the time if you need anything else.”

Heimdell smiled pleasantly. “I understand you’re looking for a house. What are your requirements and expectations?”

“It’s not so much expectations as limitations.” Dekkard gestured to the armchair. “We might as well sit down.” Once all three were seated, he went on. “We’re not endowed with inherited wealth. So we’re looking for something modest in a decent neighborhood, preferably with three bedrooms, a sitting room, a dining room, a study, and two bathrooms . . . and a garage. What would something like that in good repair run . . . or is there anything?”

“Houses here are cheaper than in Machtarn. I’d say, based on what I’ve reviewed, you could get all of that in a nice neighborhood for around four thousand marks. Five thousand bordering the North Quarter.”

Dekkard looked to Avraal.

“What would another thousand marks possibly gain us?” asked Avraal. “And what would be the additional fees and taxes?”

“You’d have to make a deposit to cover half the house taxes for the year, and the property legalist fees are included in the house price. Usually the additional costs are less than five percent. Another thousand marks would give you more space or more rooms . . . or a slightly better location. It just depends on the property.” Heimdell shrugged and paused. “It might be better if we took a drive, and I show you houses that are possibilities. If any interest you, I can arrange for you to see them.”

Avraal nodded.

“With one condition,” added Dekkard. “One of us drives. We also need to learn to get around Gaarlak.”

Kelliera Heimdell offered an amused smile. “Of course. Now?”

“Now,” said Avraal firmly, rising to her feet.

Before the three left the office Dekkard turned to accept a card from Namoor Desharra, with the address of Myram Plassar, then hurried to catch up to Avraal.

Copyright © 2023 from L. E. Modesitt, Jr.