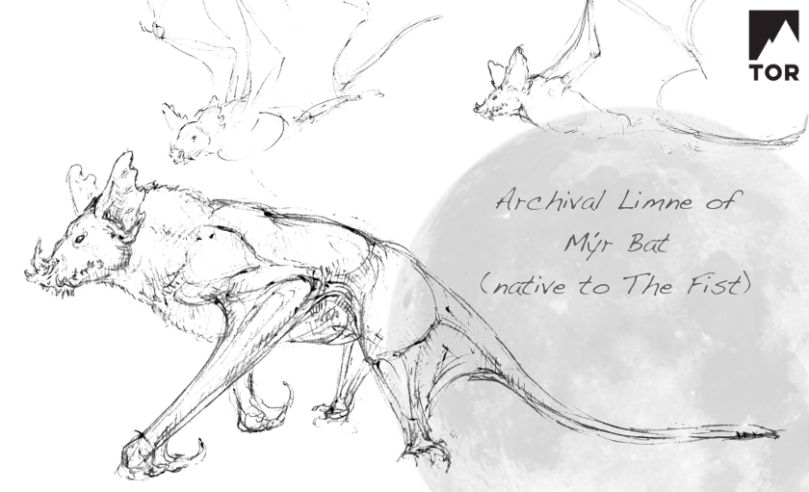

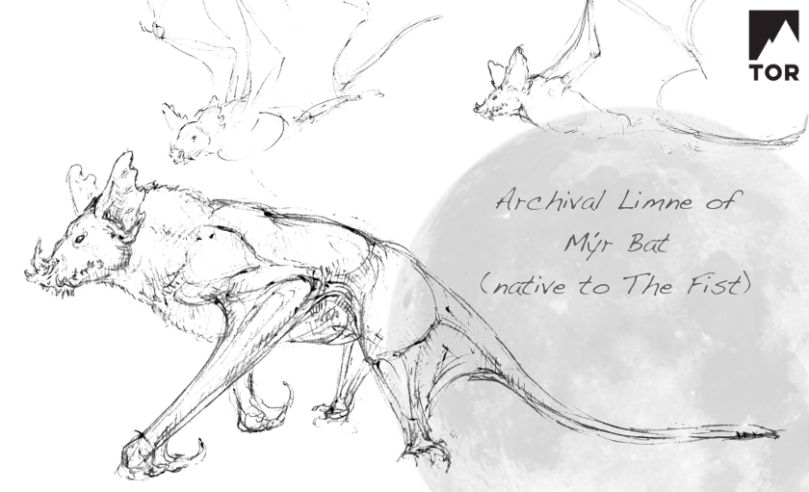

Is a Bat a Dragon? We Asked James Rollins

Visiting Scholar James Rollins provides dragonly analysis on the cryptozoological categorization of bats.

Visiting Scholar James Rollins provides dragonly analysis on the cryptozoological categorization of bats.