The only thing as infinite and expansive as the universe is humanity’s unquestionable ability to make bad decisions.

The only thing as infinite and expansive as the universe is humanity’s unquestionable ability to make bad decisions.

Humankind ventures further into the galaxy than ever before… and immediately causes an intergalactic incident. In their infinite wisdom, the crew of the exploration vessel Magellan, or as she prefers “Maggie,” decides to bring the alienstructure they just found back to Earth. The only problem? The aliens are awfully fond of that structure.

A planet full of bumbling, highly evolved primates has just put itself on a collision course with a far wider, and more hostile, galaxy that is stranger than anyone can possibly imagine.

Gate Crashers will be available on June 26th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Chapter One

It was a cold, dark night in deep space. Of course, that’s the sort of night experienced spacers preferred. A hot, bright night meant you’d flown into an uncharted star. Such nights were known for their brevity.

The American-European Union Starship Magellan streaked through the vacuum at a sliver under half light speed. When christened sixty-two years ago, Magellan was heralded by reporters, tech writers, and industry mouthpieces as a marvel of engineering, which she was.

They also described her using words like graceful, elegant, and sleek, which she most certainly was not. The sight of Magellan brought to mind a seventeen-hundred-meter-long mechanical jellyfish with an inverted bell made of a giant dinner plate, drainage pipes, and an entire box of novelty bendy straws.

Buried beneath a jacket of water built into the ship’s hull to shield them from cosmic radiation eager to redecorate their DNA, the crew chilled through the dull bits of their journey in cryogenic pods set at less than a tenth of a degree above freezing. Hearts beat once every other minute. Blood flowed with the speed of buttercream frosting. Dreams played at a pace that would make a Galápagos tortoise glance at its watch.

The year was 2345, and Magellan’s 157 peoplecicles were just a sliver over thirty light-years from Earth. As they slept, Magellan was hard at work. She balanced the deuterium flow to the beach-ball-sized star in her stern, which was the source of her power, extrapolated the trajectories of thousands of bits of stellar dust no bigger than a flake of crushed pepper, and then used her battery of navigational lasers to vaporize those flakes on intercept courses.

One would usually attribute the quaint human tendency to anthropomorphize machines as the reason the pronoun she was applied to a starship. However, Magellan herself had decided long ago that any entity that selflessly nurtured so many helpless children must be female.

While pondering her myriad duties, one of her ranging lasers blinked, beeped, and generally made a nuisance of itself. Magellan gave it the cold shoulder for several nanoseconds before she caved to its persistence and queried its data packet to see what was so important it couldn’t wait a millisecond.

What she found caused her only the second moment of confusion in her sixty-two years of operation. The first happened many years ago when her chief engineer had tried to explain the appeal of chewing tobacco, with little success.

This time was worse. The laser revealed an object, sixteen meters long, less than two light-hours ahead of her. After a few milliseconds of data streamed in, Magellan determined, while abnormally large for space dust, the object did not pose a direct threat, as it was not on an intercept course. Curiously, it was not on any course at all.

Out of tens of millions of particles Magellan had spotted, projected, and vaporized, she’d never observed one that wasn’t moving. You didn’t end up in the void between stars without inertia; it just wasn’t possible. As an exploration vessel, her software possessed a certain baseline curiosity, and the paradox of the object ate at her processors. However, her ability to make command-level decisions was deliberately limited to the protection of her crew while they were incapacitated. Since the object didn’t pose a danger to crew safety, her programming didn’t permit a course alteration. If she wanted more than the meager data she could acquire in a two-hundred-million-kilometer flyby, she’d need to wake the captain.

Safely waking from cryosleep was a two-hour ordeal. As the body slowly warmed, neurons fired with the vigor of an asthmatic 4×400 relay team. Imagine the pricking-needles sensation felt when an arm falls asleep and map it over one’s entire body. If that weren’t enough, the sluggish metabolism of cryo caused a buildup of the same toxins that result from a three-day bender.

This marked Allison Ridgeway’s sixty-second cycle. As her consciousness stirred, Allison drew on the considerable experience she’d acquired in college to deal with the worst hangover imaginable. She kept her eyes closed until they stopped lying to her, placed one foot on the ground to anchor her sense of balance, then grabbed the pod’s hydration tube and sucked down as much fluid as she could stomach. After an eternity, Allison sat up and pondered how to use her feet.

Something was missing.

“Maggie?”

“Yes, Captain Ridgeway?” answered a soothing voice that sounded suspiciously like her mother.

“Why don’t I have a soul-crushing headache?”

“I don’t know, Captain, but I can probably synthesize a compound to approximate the effects.”

Allison smiled. It was tough knowing if Maggie, as she liked to call the ship, was still naïve or if she had developed a dry sense of humor. She suspected the latter.

“How long have I been out?”

“Three weeks, two days, seven—”

“Three weeks?” she asked. Crews woke for one week per year to keep their minds fresh. They’d gone through the cycle less than a month ago. “We just crossed the thirty. We won’t reach Solonis B for eight months.”

“That’s correct, Captain. However, I require your judgment.”

“You mean you require my authorization to indulge your judgment.”

The Magellan reflected on this for a moment, and decided there was no reason to lie. “Yes, Captain. Please join me on the bridge.”

“I’m not dressed.”

“You’re the only person awake.”

“I’m freezing and covered in cryo snot, Maggie.”

“Yes, of course. I await your arrival on the bridge once you’re more comfortable.”

“It’s all right. You’re in a hurry, I get it.”

Allison staggered along the wall toward the showers. The hot water rinsed away the cold, viscous fluid clinging to her body, which felt and smelled like used fryer oil. She was glad not to wake with the headache for once.

Allison put her hair in a towel and walked to her locker. She retrieved a plush, embarrassingly expensive pink bathrobe with matching kitten slippers. It was a small luxury she afforded herself, and she sank into the depths of its soft warmth.

She moved to the RepliCaterer and finished her waking/hangover routine with an order of hot coffee with double cream, two sugars, and a grape popsicle, which it produced in seconds. The RepliCaterer was an amazing device. Half waste-recycling plant, half food processor. It was best for morale to ignore which half the food came from. Crews had long ago named it the DAQM—Don’t Ask Questions Machine. Feeling vaguely human, the fuzzy pink captain made her way to the transit tube.

The bridge was awash with the gymnastic light of holograms and the dry breeze of air processors. It had the sterile yet lived-in look of a small-town doctor’s lounge. Allison dropped into her chair and spilled the remains of her coffee into her lap.

She grabbed the towel from her head to rescue her bathrobe from the brown stain. “One of those mornings.”

“Actually, Captain, it’s 1537.”

“The worst mornings usually start in the middle of the afternoon, Maggie. So what’s important enough to wake me eight months early?”

A cloud of pitch black expanded in the air in front of Allison’s chair as an intense holographic field persuaded the ambient light to saunter off somewhere else. A faint, blue, 3-D grid materialized. A small icon representing the Magellan appeared at the center, with course and velocity information in red.

There was a green circle far in the simulated distance with nothing but a single pinprick of white at its center. It, too, had course and velocity data displayed in red, but they both read zero.

“Magnify, please.” A small box opened next to the green circle. The image inside was just a larger smudge. Allison grimaced, then glanced at the radar returns and spectrographic data. “Right, then. Our object is sixteen meters long with a high metal content. Great, we’ve discovered an iron meteor.”

“Captain,” Magellan purred, “is there anything else about this object you find interesting?”

Allison knew she was being patronized, but studied the numbers. With a flash of realization, her finger launched toward the ceiling, then pointed at the blurry image. “It’s not moving. How does a rock get into deep space without momentum?”

“I arrived at the same conclusion; hence my decision to wake you.”

“Good work, Maggie. What’s our time to flyby?”

“Forty-seven minutes, six seconds from now.”

“How close will we be able to get if we alter course?”

“At our current velocity, we will pass within ten light-minutes of the object.”

“That’s still more than an AU. If we start a full deceleration right now, how much of that can we cut?”

“Another four and a half million kilometers.”

“Not nearly enough.” Allison churned through a dozen other possibilities, but they were all worse.

Even with Magellan’s powerful eyes and ears, a flyby from such distance wouldn’t improve on the smudge by much.

Allison fixed on her decision. “Well, nothing for it. Maggie, begin a full decel and plot a spiral course toward the object. We should be close enough by the third pass to get decent readings. Once we’ve satisfied your curiosity, we’ll resume previous course and speed.”

“Immediately, Captain.”

“Why do I get the sense of playing a bit part in Kabuki theater?”

“I’m sure I don’t know what you mean, Captain.”

“Uh-huh.” Allison felt a sudden kinship with harps.

Maggie poured a flood of deuterium into the nuclear furnace at her stern. A torrent of enraged electrons charged through the scaffolding of superconducting conduits connecting the reactor to the engines at the bow.

The engines were front-mounted because gravity propelled Magellan, at least that’s what space was led to believe. In fact, protected behind the concave shield that formed her bow, bulky generators created and focused gravitons into a point ahead of the ship, duping the surrounding space-time into perceiving a large mass. Fooled by this theatrical bit of three-card monte, space obligingly curved itself into a well and pulled the ship forward. This was the origin of the slang term yank, as opposed to the more colorful etymologies proposed by several limericks popular among dockyard workers.

Allison felt the almost imperceptible lurch as the internal gravity adjusted to compensate for the appearance of a new gravity well a few degrees off their heading. Turn sharper than that, Magellan’s keel would break under the stress. With little to maneuver around in deep space, this wasn’t usually an issue. Seconds flew by as Allison tried to stay on top of the riot of raw data the various sensors returned.

“Are there any other crew members you’d like me to wake?” Magellan asked.

“So I can get blamed for putting them through two hours of amateur acupuncture and vertigo just to see an asteroid? No, none of them have done anything to deserve that kind of treatment for at least twenty years. Then again, there was that spittoon incident . . .”

“Chief Engineer Billings threw his supply of chew into a waste receptacle after that unfortunate event, Captain,” the ship added in defense of her personal physician.

“Really? He went cold turkey?”

“I don’t believe he switched to turkey, Captain.”

“No, it’s a . . . never mind. So he quit?”

“Yes, for three days. Then he started growing a tobacco plant in hydroponics.”

“It’s the thought that counts, I suppose.”

Crimson numbers on Allison’s display trickled down as the range fell. Telescopes slowly resolved the smudge into a slightly more coherent blur, which wasn’t much help. The spectrograph was another matter. It reported that the object was comprised primarily of titanium, with traces of several other metals, which was as likely to occur naturally as a petrified tree made of Portland cement. Allison was excited, and more than a little anxious.

Magellan broke the silence. “Captain, I’m detecting a signal coming from the object.”

“Why are you only detecting it now?”

“The signal is weak. I mistook it for background static, but after correlating the last several hours of data, a pattern emerged.”

Allison realized she was sweating. She felt torn between the hope of hearing a completely benign radio echo and the excitement and danger of discovering something more interesting. “Let’s hear it, then,” she said at last.

What came through the speakers had a musical quality. Specifically, the sound of a pipe organ being fed through an industrial shredder, complete with an organist in a mad dash to finish a concerto before the hammers reached his seat. Yet as alien as it was, she knew instinctively the sound wasn’t static. There were patterns and rhythm in the noise. Allison Ridgeway, captain of the AEUS Magellan, successfully beat back the impulse to hide under her chair.

She took a moment not to vomit. “Maggie, forget the spiral course. Bring us to a zero-zero intercept, five clicks from the object. Wake everyone. I want that thing in my—I mean, your—shuttle bay yesterday. And get the QER online. I need to talk to Earth.”

“Immediately, Captain Ridgeway.” Magellan tried not to let any smug vindication creep into her tone.

Without success.

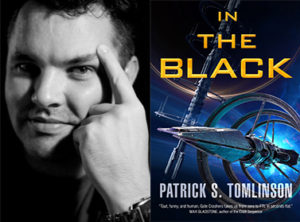

Copyright © 2018 by Patrick Tomlinson

Order Your Copy