Welcome to Throwback Thursdays on the Tor/Forge blog! Every other week, we’re delving into our newsletter archives and sharing some of our favorite posts.

In December of 2011, Rudy Rucker’s autobiography Nested Scrolls was published. In it, Rucker revealed his true-life adventures as a mathematician, transrealist author, punk rocker, and computer hacker. In this essay, from the Tor Newsletter, Rucker shared some important moments from his past, and explained how he decided to structure his autobiography. We hope you enjoy this blast from the past, and be sure to check back in every other week for more!

By Rudy Rucker

The thing I like about a novel is that it’s not a list of dates and events. Not like an encyclopedia entry. A novel is all about characterization and description and conversation, about action and vignettes. I decided to structure my autobiography, Nested Scrolls, like that.

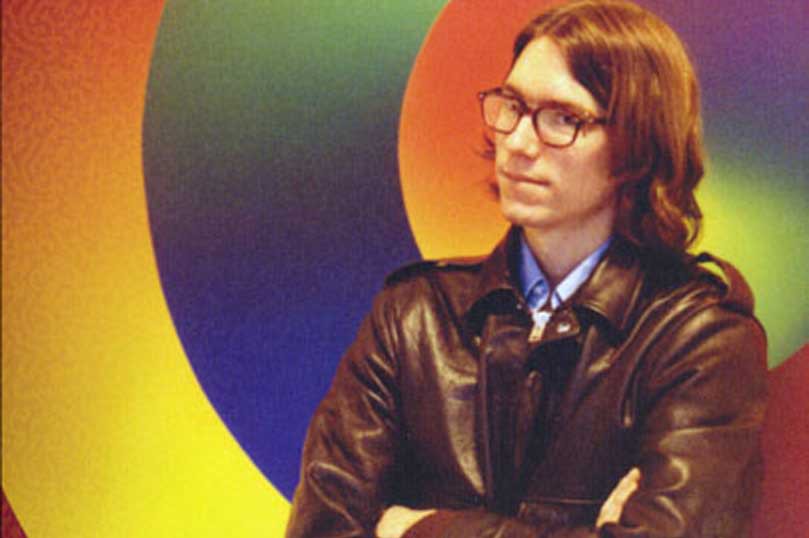

This is a picture of me in my senior year at college. At that time I had the idea that Army-issue-style transparent glasses frames were cool. My roommate and I were writing things on the walls.

Plot? Well, a real life doesn’t have a plot that’s as clear as a novel’s. But, as a writer, I can think about my life’s structure, about the story arc. And I’d like to know what it was all about. In writing my autobiography, I came up with a few ideas.

The picture below shows me with a “magic door” in Big Sur, California in 2008. I depict this a portal to a parallel world in my novel, Mathematicians in Love.

You might say that I searched for ultimate reality, and I found contentment in creativity. I tried to scale the heights of science, and I found my calling in mathematics and in science fiction. You don’t have to break the bank of the Absolute. Learning your craft can be enough.

This picture shows me as the singer of the Dead Pigs punk rock band in Lynchburg, Virginia, 1982. This was a time when I was still drinking and smoking pot. But eventually I found a way to stop. Once you’re in your forties, Jack Kerouac and Edgar Allen Poe aren’t good role models. They died in their forties.

Here I am with my daughter Georgia in 1973. In some ways I like children better than grown-ups. Their minds are more open, less encumbered. As a youth, I was a loner. But then I found love and became a family man. I’ve spent a lot of time with my wife and our three children over the years. And now we have grandchildren. New saplings coming up as the old trees tumble down.

Here I am selling prints at the Westercon in Pasadena, 2010. I’ve taken up painting as a hobby. It’s a lot harder, at least for me, to sell a print or a painting than a story or a book! I’ve had a number of careers. Initially I was a math professor—math always came easy for me. Nothing to memorize! Then I took up writing, really that’s my core career. But, even with thirty-odd books out, writing doesn’t pay very much.

So I spent the last twenty years working as a computer science professor in Silicon Valley. Riding the wave. It was a blast. And eventually I even got good at teaching, mutating from a rebel to a somewhat helpful professor.

Whatever I did, I never stopped seeing the world in my own special way, and I never stopped looking for new ways to share my thoughts.

This article is originally from the December 2011 Tor newsletter. Sign up for the Tor newsletter now, and get similar content in your inbox every month!