$3.99 eBook Sale: February 2023

It’s a new month and that means…NEW EBOOK DEALS! Check out the below to find out which books you can snag for only $3.99.

It’s a new month and that means…NEW EBOOK DEALS! Check out the below to find out which books you can snag for only $3.99.

It’s November, which means we are entering the last month of our Fantasy Firsts program. We wanted to say thank you with a special sweepstakes, featuring ALL the titles we highlighted this past year. That’s 40 fantastic reads from 40 different series to add to your TBR stack! Plus, we’re including an added bonus: two sandblasted book dragon mugs, so you can enjoy your coffee or tea in style while you read.

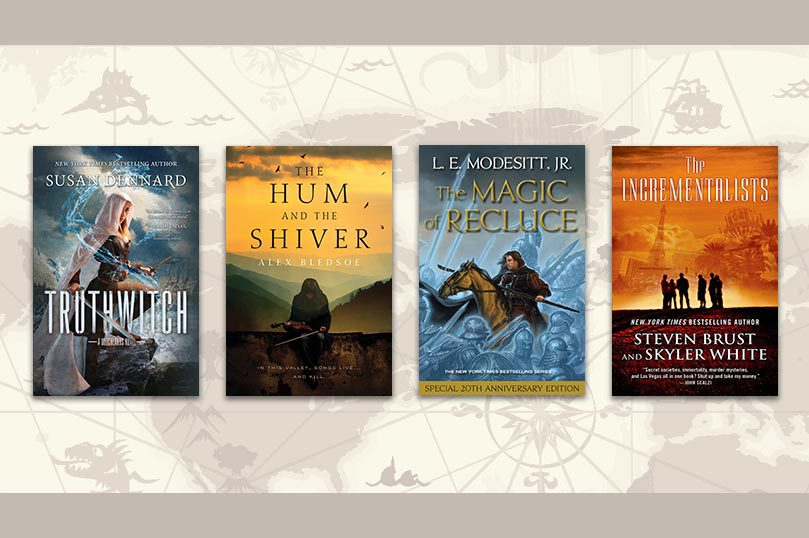

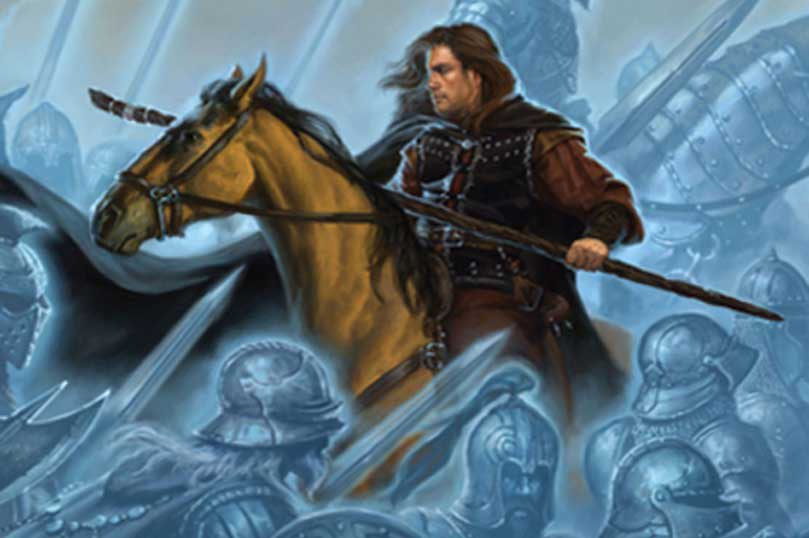

Our Fantasy Firsts program continues today with an ebook sale! The next book in L. E. Modesitt, Jr.’s Saga of Recluce series, Recluce Tales, will become available January 3rd. This month we are making it easier to get started on this series by offering the first book, The Magic of Recluce, for just $2.99.

Looking for a great fantasy read? We are currently offering the chance to win four fantastic titles on Goodreads.

Continuing our Fantasy Firsts program, The Magic of Recluce author L. E. Modesitt, Jr. discusses taking an “economic” approach to writing fantasy.

Our Fantasy Firsts program continues with an extended excerpt from The Magic of Recluce, the first book in L.E. Modesitt, Jr.’s bestselling fantasy series set in the magical world of Recluce.

Once again Tor (Booth# 646) continues our wildly popular *in-booth signings and giveaways, offering you a chance to meet your favorite authors up close and personal and pick up free books. Friday, June 6th 10:30 – 11:30 am Putting the Science in Science Fiction John Scalzi, L.E. Modesitt 12:00 pm Tor Booth (#646) Signing: Elizabeth Bear, Range of…

By L.E. Modesitt, Jr. While I always wanted to be a writer, I didn’t start out writing either science fiction or fantasy. In fact, my first published works were poems, and my primary collegiate fields of study were politics and economics. For the record, writing was third. But when I left the Navy, after a…

See upcoming releases.