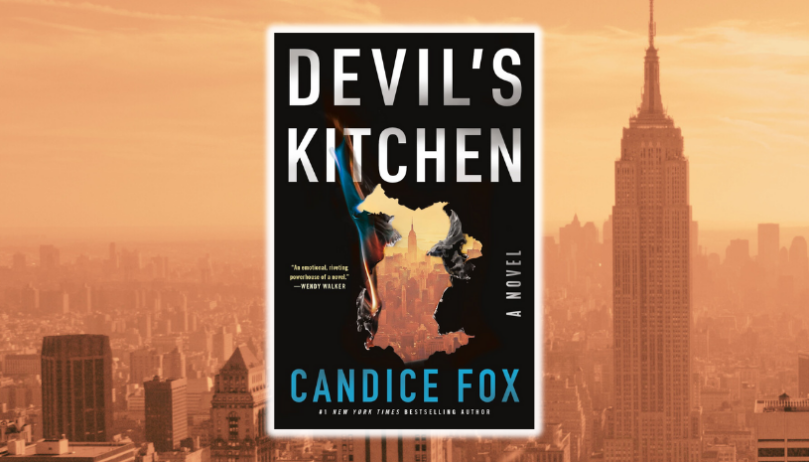

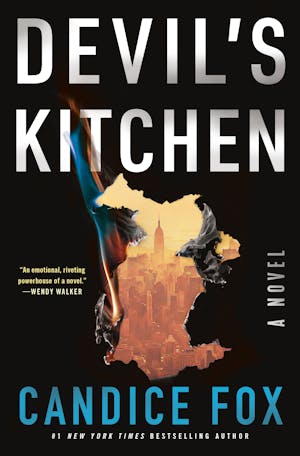

Devil’s Kitchen is a fast-paced, heart racing thriller from Candice Fox, “a bright new star in crime fiction.” (James Patterson)

Devil’s Kitchen is a fast-paced, heart racing thriller from Candice Fox, “a bright new star in crime fiction.” (James Patterson)

The firefighting crew of Engine 99 has spent years rushing fearlessly into the hot zone of major fires across New York City. This tight-knit, four person unit has faced danger head-on, saving countless lives and stopping raging fires before they can cause major destruction.

They’ve also stolen millions from banks, jewelry stores, and art galleries. Under the cover of saving the city, these men have used their knowledge and specialist equipment to become the most successful heist crew on the East Coast.

Andy Nearland, the newest member of Engine 99, is good at keeping secrets. She’s been brought on to help with their biggest job ever—hitting New York’s largest private storage facility, an expensive treasure trove for the rich and famous.

She’s also an undercover operative, charged with bringing the crew to justice.

Keeping Andy’s true motives hidden proves more and more dangerous as tempers flare and loyalties are tested. And as the clock counts down to the crew’s most daring heist yet, her cover might just go up in flames…

Devil’s Kitchen will be available on June 4th, 2024. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

ANDY

“We know you’re a cop,” Matt said.

Andrea had been waiting for those words. All the way out to the forest, as they pulled off the highway and onto the thin dirt road. The unsteady headlights between Matt’s and Engo’s shoulders cast the trees in a strangely festive gold. The killing fields. In a way, Andy had been waiting for the words a lot longer than that. Every morning and every night for almost three months. The potential for them clinging to the lining of her stomach like an acid.

We know.

Now she was kneeling on the bare boards of a run-down portable building in the woods, the sound of boats on the Hudson nearby competing with the moan of skin-peeling wind. The corrugated-iron roof rattled above all their heads. The property—a massive, abandoned slab of woods that probably belonged to some absent billionaire who’d had ideas of building a house here once—was dead silent beyond the little shack. Andy knew she was in a black spot on the river’s otherwise glittering edges, so close to safety, yet so far away. Ben was breathing hard beside Andy, sweating into his firefighting bunker uniform. The reflective yellow stripes on his arms were trying to suck up any and all available light. There wasn’t much. Matt, Engo, and Jakey were faceless silhouettes crowding her and Ben in. Strange what a person will long for at the end. A sliver of light. To breathe the sour air unfettered, as Ben did. They’d taped her mouth.

Matt put his gun to Ben’s forehead, nudged it hard so that his head snapped back.

“You brought a fucking cop into the crew.”

“She’s not a cop! I swear to God, man!”

“I raised you,” Matt growled. “I found you in a hole and I dug you out and this is how you want to play me?”

“Matt, Matt, listen to me—”

“Benji, Benji, Benji.” Engo stepped forward, put his three-fingered hand on Ben’s shoulder. “We know. Okay? It’s over. You got a choice now, brother. You admit what you’ve done, and maybe we can talk about what happens next.”

“She’s not a cop!”

I’m not a fucking cop! Andy growled through the tape. Because it’s what she would say. Andrea “Andy” Nearland, her mask. She wouldn’t go down quiet. She would fight to the end.

Engo came over to her and tried to start in with the same faux pleasantries and soothings and bargains and she flopped hard on her hip, swung her legs around, and kicked out at his shins. He went down on his ass and she let off a string of obscenities behind the tape. Andy had always hated Engo. Andy the mask. And the real Her, too. Jake got between them. Little Jakey, who had until now been hovering in the corner of the dilapidated portable and gnawing on the end of an unlit cigarette, muttering worrisome nothings to himself.

“Get her back on her knees.”

Jakey came over and helped her up. His hand was clammy on her neck.

Don’t fucking touch me!

“Benji,” Big Matt said. “There’s an out here. I’m giving you an out. You gotta take it.”

“I don’t—”

“Tell us that you turned on us. That’s all you have to do, man.”

“She’s not a cop!”

“Just tell us!”

“Matt, please!”

“Tell us, or I’m gonna have to do this thing. I don’t want to do it. But I will.”

Andy looked at Ben. Met his frantic gaze. She saw it in his eyes, the scene playing out. Andy taking the bullet in the brain. Her body ragdolling on the floor. Ben next. All the vigor going out of him, like his plug had been yanked from the socket. Matt, Engo, and Jakey strapping firefighting helmets onto their dead bodies and lighting the place up around them. Driving back to the station car parked at Peanut Leap. They’d make the anonymous call to 911. Then respond to Dispatch when the job came over the radio.

Hey, Dispatch, we’re up here anyway. Engine 99 crew. We took the station car for a cruise and we have basic gear on us. We’ll head out there while the local guys get organized.

It would look like an accident. The crew had taken the station car out for a spin, parked to watch the lights on the river and sink beers, and picked up a run-of-the-mill spot-fire call. They’d rolled up to the property, spotted the portable that had probably served as a construction-site office once, starting to smoke out. Ben and Andy had taken the spare gear from the back of the car and rushed in ahead of Matt and the rest of the crew, no idea that the blazing building was full of gas bottles and jerry cans that some local cuckoo had been hoarding.

Kaboom.

A tragedy.

Oh, there’d be an inquiry, of course. Wrists would be slapped—about the rec run with the station car, the beers, the half-cocked entry. There would be whispers, too. Especially after what happened to Titus.

But then everybody would cry and forget about it.

Matt and his crew did that: they made people forget.

Andy watched Ben weigh his loyalties. His crew, against the cop he’d brought in to destroy them.

“I don’t want to do this, Ben,” Matt said. The huge man’s voice was strained. He shifted his grip on the gun. “Just tell us the truth.”

The wind howled around the shack and the boats clanged on the river and Little Jakey started to cry.

THREE MONTHS EARLIER

BEN

Fire is loud. It calls to people. Probably had been doing that since the dawn of time, Ben guessed. When it was old enough, when it had evolved through its hissing and creeping and licking phase and was a good-sized beast learning to roar—that’s when they came. Stood. Watched. Felt the heat on their cheeks and felt alive and part of something, or some hippie shit like that.

By the time Ben’s boots landed on the wet sidewalk of West Thirty-Seventh Street there were huddles of people in darkened doorways across the street and gawkers hanging out of apartment windows above them. The pinprick white lights of phone cameras. He hardly noticed, was hauling and dumping gear onto the concrete, his mind tangled up with the next eighteen steps. Engo had a cigar clamped between his jaws and was drenched in sweat, started stretching the line.

“This is a mistake,” Ben told Matt as the chief jumped down from the engine. The flashing lights were making Matt’s angry red neck stubble a sickly purple.

“It’ll be fine.”

“A fucking fabric store?” Ben ripped open the hatch on the side of the engine and started grabbing tools fast and efficiently. A looter in a floodlands Target. “It’s a tinderbox.”

“The building is right on our path. It was the best way in.”

Clouds of singed nylon were pouring out of the building above them. “It’ll go up. And Engo and Jakey won’t be able to—”

“Stop bitching, Benji.”

Ben stopped bitching, because you didn’t bitch too long at Matt. By now, two windows on the third floor of the fabric store had blown out and the crowd in the street had doubled. The windows were glowing up there, not just the ones that were blown. Ben had been doing this ten years, longer. The window glow told him the fire was big enough that it was probably into the foundations.

He tanked up, slapped on his helmet, shouldered a gear bag, and went in. Engo was in front, of course, his chin up, the hose hanging over his arm like a great limp dick. A guy walking into a fancy museum. Engo made a show of marching into fires like that, like it was all routine. Like nothing was a big deal. What happened? Granny left the iron on? Ben had seen the guy step over bodies as if they were kinks in a rug. His tank was unhooked because smoke worried him the way water worried fish.

Ben dropped his hose, split from Jakey and Engo, and went down the stairs while they went up toward the fire. Things passed before him, curiosities his mind would pick over later as he tried to sleep. Walls of buttons in a thousand shapes and colors. Giant golden scissors. Cutting tools and rulers. There were stacks of leather lying folded on shelves, colors he hadn’t imagined possible. He was glad they’d decided to set the spark device that ignited the fire on the third floor. It was all fur and feathers on the basement level—this part of the store was going to vaporize when it caught.

Ben dropped his bag and helmet. The bag was so heavy with tools it shook the floor, made a jar of pins jump off the nearby cutting counter. He took a knife from his belt, slit a square in the carpet, raked it back, and exposed the boards. Lifting up six floorboards with a Halligan tool took fifteen seconds. He dropped his gear bag down onto the bare earth below the building and slipped in after it, landing right on top of the concrete manhole. He didn’t have a pit lid lifter but the Halligan did the job, slid nicely into the iron handle of the forty-pound manhole cover. He adjusted his mask, worked his jaw to make sure it was sealed tight before he popped open the cover and stepped down into the blackness.

Something about being surrounded by toxic gas makes a guy breathe harder. He’d thought about that for the first time as he hauled bodies for overworked paramedics in COVID times, then while putting out car fires while the NYPD doused the streets in pepper spray during the George Floyd days. It had occurred to him again now in the dark, working his way along the disused, hand-bricked tunnel beneath West Thirty-Seventh Street, he thought of the hydrogen sulfide swirling in the air around him, built up from decades of moss and sewage and whateverthehell percolating in the old, sealed subway access. It made him suck on the oxygen like a hungry baby at the tit.

He didn’t use the flashlight down here. Engo had tried to argue that H2S wasn’t that flammable, and an LED didn’t spark like that anyway, but Ben wasn’t going to turn that corner of New York into Pompeii because he didn’t like the dark. He had about eleven minutes to get where he was going, do the job, and get back again. The blindness would make the timing tight. The radio crackling in his ear canal with the voices of the crew behind him made him twitchy.

“Engo, you on-site?”

“Yeah, boss. We got a nice little campfire here.”

“Ben?”

“Checking for a secondary ignition site,” Ben lied. His voice felt trapped behind the mask.

“We better black out the whole block,” Matt said. “We don’t know who shares a distributor.”

Ben fast-walked, imagining Matt on the street, ordering the backup crews, who were probably already arriving from Ladder 98, to shut down the power to the whole Garment District. The guys from 97 and 98 would probably think that was over the top, that blacking out the singular block would do. But Matt needed to make sure that not only the fabric store was powered off, but also the jewelry store on West Thirty-Fifth, where Ben was heading.

Left, right, left, he reminded himself. Just like the marching call. He turned the last corner, walked for three minutes, his gloved fingers trailing the wall, all sorts of landscapes passing under his boots, most of them wet and squelching. He found the steppers he was looking for—rusty iron rungs concreted into the wall—dropped his gear bag, and went up. His arms were shaking as he lifted the second manhole cover. Nerves.

It had been a year or more since they’d done a high-end job like this, something that required blueprints to be memorized and on-site scouting in the lead-up. A dry spell ended. Ben didn’t like these kinds of jobs; scores they needed.

Don’t rob when you’re broke. That was a mantra he’d always believed in. Desperation makes guys stupid, dissolves trust. Because at the end of the day, did Ben really know for sure that Matt had gotten the best fence for this take? Someone who could move what they stole tonight without making ripples? Or had Matt settled, because the crew chief had three ex-wives with their hands out and a bun in the oven with baby mama number four? And did Ben really know for sure that Jakey had double-checked on all the construction sites in the Garment District for late-night workers who might be in the tunnels? Did Jakey know the local police response times? Or was the kid into the horses again? Was he hocking old PlayStation games to fend off loan sharks?

Ben realized, as he hauled his gear up through the manhole and into the two-foot-tall crawl space beneath an apartment building on Thirty-Fifth, that he didn’t trust his own crew on a job anymore.

And that was bad.

But there were worse kinds of mistrust.

There was the one that had made him write the letter to the detective.

Ben lifted the manhole cover back into place, raked his oxygen mask off, and lay panting on the compacted dirt floor. The crawl space was as black as the tunnel, but years of working in roof cavities and basements and tunnels and collapsed buildings had given Ben the ability to maneuver in the dark like a night creature. He found the flashlight on his belt, clicked it on, and got his bearings. Wide, raw-cut floor beams stretched into the nothingness just inches above where he lay. They’d probably been built when they still called this place the Devil’s Arcade, and it was an army of prostitutes and bootleggers, and not fancy types shopping for diamonds, stamping over them. Ben started crawling west, found a gap in the brick foundations that separated one building from another, and kept on. A hundred yards from the manhole, three buildings over, the subsurface power-distribution board belonging to the jewelry store was just where he expected it to be, bolted to a brick strut.

He pulled wire cutters and a charge tester and the bug from a vest strapped under his turnout coat, started working the board to insert the bug. Sweat ran into his eyes. His mind kept trying to wander away from what his fingers were doing and drift two blocks over to the fabric store, to twenty-three-year-old Jakey, shoulder-to-shoulder with an eight-fingered, potbellied psychopath who wanted to die in a blaze of glory. The two of them battling a decidedly glorious blaze. The men trying to let the magnificent thing eat through enough cotton and satin and jersey and whatever else to give Ben the time he needed to do what he had to do; but not so long it would become a monster and turn and eat them, too.

Ben finished installing the bug in the jewelry store’s security system and was shifting around to crawl back to his gear bag and tank and the manhole three buildings away when he heard a woman’s voice.

“Hello?”

Ben froze. Instinct made him flatten on the dirt like a threatened lizard. His toes were curled in his boots. His eyes bulged and his lungs expelled all the air that was in them. He heard the floorboards somewhere to the right of where he lay creak with footsteps.

The radio in his ear crackled.

“Engo and Jakey, you got it in hand?”

“Yep. Yep. We got it.”

“It don’t look like it from here.”

“I said we got it.”

“Ben, give me an ETA. They need you up there.”

Ben didn’t breathe. Whoever was in the jewelry store above him walked across the boards right over his head. He heard a muffled snap, and then, even through the layers of carpet on the boards above him, he saw the glow of a light.

“Fuuuuuuck,” he mouthed.

“Hello?”

“Ben, give me a sitrep,” Matt insisted.

He didn’t speak. Slowly, achingly, he lifted his hand from the dirt and reached for the radio on his shoulder. He clicked the transmit button twice, the code for trouble.

There was a long pause. Ben counted his breaths. The counting made him think of time. Seconds ticking off. With a recognition so filled with dread it sent a bolt of pain through his spine, he remembered the PASS alarm on his belt and reached down and shook the safety device so it wouldn’t sound a pealing alarm at his immobility. Sweat was dripping off his eyelashes.

“Two for hold, three for abort,” Matt finally said. Ben could hear the tightness in his chief’s voice. He clicked the radio twice.

Another three minutes. Ben counted them. The woman in the jewelry store moved some stuff around, opened and closed a cabinet.

“Ladder 98 crew are comin’ up to join you, Engo,” Matt said. Ben could hear the quiet fury in his voice now.

“Tell those pricks we got it!”

“I’m telling you to haul ass!” Matt said. “They’re comin’!”

Ben swore under his breath. It probably sounded to anyone monitoring the radios that Matt had been talking to Engo, encouraging him to get the fire under control before another crew came in and claimed the knockdown of the fire. But Ben heard the real message. Matt was telling him to haul ass out from under the jewelry store and back to the fire before the guys from 98 geared up and entered the site, climbed to the second floor, and asked where the hell Engine 99’s third guy was.

Or worse, they came looking for him. In the basement, maybe, where he’d opened up the hole in the floor to access the tunnel.

The light clicked off above him. Ben guessed whoever was in the store had decided the sound she heard wasn’t a person. He counted off ten breaths, then slithered for his life back to the manhole, tanked up, and popped the cover and dropped his gear into the shaft.

He was sprinting so hard down the home stretch his fingers almost missed the steppers on the wall under the fabric store. He grabbed on and yanked himself to a stop, almost slipped in the toxic sludge. Ben climbed to the top of the ladder, shouldered open the manhole, got out and threw it back into place, then heaved himself up through the hole he’d cut in the floor. His body was screaming at him to just lie there, take a minute. Three-quarters of his oxygen tank was gone just from his own panicked breathing. The air in the mask tasted rubbery and thick. Soon it would start shuddering on his face, a sign he was about to max out. He rolled over instead, got up, and dragged a heap of furs to the edge of the hole. He lit them with a cigarette lighter and bolted up the stairs.

He arrived in the foyer as the Ladder 98 guys were marching up the stairs to the second floor. Ben came up behind them. He couldn’t think what else to do. A guy he didn’t recognize whirled around on him.

“Da fuck?”

“We got a secondary ignition site in the basement,” Ben said. The Ladder 98 guys looked at each other for a moment, probably trying to decipher how the hell a secondary fire could start on the basement level of the building when the main fire was on the third floor. And what the hell Ben was doing down there looking for a secondary site before his own crew had taken hold of the primary site. But they shook it off. They probably guessed Engo was behind the split in manpower, and they’d all seen stranger things happen with ignition sites. Fires creeping through walls and popping up in two apartments on opposite sides of the same building. Fires reigniting two weeks after they were put out. Fire had no rules. It was the only magic left in the world.

“Go to your crew,” the 98 guy said. “We’ll take the basement.”

Ben watched them go. He could see flames licking up the walls of the basement stairwell. Just as he’d predicted, the basement was already just a room full of ash and memories.

***

It was 4 A.M. and they were in the squad room before anybody could talk about it. Matt’s crew had a room of their own, mainly because nobody from the other crews could stand the idea of Matt coming in and sitting down to watch the TV and them having to sit there with him like there was a full-size lion lounging on the end of the couch. Ben and the guys, they all stank. Ash and sweat and monoammonium phosphate. Engo was in his armchair nursing his paunch, a wet basketball under his T-shirt. Matt was throwing shit around in the kitchenette. Jakey stood by the door, wincing like he was expecting to be the next thing picked up and hurled against the wall.

“Who the fuck was she?” Matt bellowed.

“How do I know?” Ben shrugged. “Hard to make her out through the floorboards.”

“It was your job to watch the ins and outs.” Matt turned and stabbed a sausage-sized finger at Engo. “You said nobody would be there.”

“So somebody pulled an all-nighter,” Engo said. “What do you want from me? I watched the store for two months. Nobody ever stayed past nine.”

“Did you watch the store?” Ben piled on. “Or did you sit in your car eating burgers and jerking off?”

“This guy.” Engo shook his head sadly at Ben.

“’Member that time you landed that nineteen-year-old on Snapchat? You let those security guards creep up on us at the Atrium.”

Engo sat grinning at him.

“What if we’d put you on watch duty at the fabric store instead of the jewelry store? Huh?” Ben asked. “What if someone pulled an all-nighter there, and you didn’t notice them? We could have had a civilian on the second floor when the fire started. Or in the basement, when I was cutting through the goddamn floor.”

“You’re really mad, huh?”

Ben held his head.

“Would it help you feel better if you took a swing at me, babycakes?” Engo tapped his stubbled chin. “Because you’re welcome to try.”

“Jesus Christ.”

“Yeah. That’s what I thought.”

“We can’t go on with this job.” Ben’s hair was still plastered to his skull with sweat. He thought about giving up and going home to bed. He made one last appeal to Matt. “The 98s saw that I was split off from my crew. They’ll know something was up. They’re going to wonder why I went looking for a second site when the primary site was getting so out of control.”

“It was never out of control,” Engo said.

“If I hadn’t got back when I did, you and Jakey would be sandwich meat between the third and fourth floors of that place right now.”

“You’re delusional.”

“It was into the foundations!”

“No it wasn’t.”

“Maybe we should think about it,” Jakey piped up, already glowing red in the neck and cheeks like a parakeet. “Because there was, uh … You know. There was the radio call, too. ‘Hold or abort.’ That’ll be on the record. That’s not good.”

“We’re not pulling the pin on this job,” Matt finally said. “We’re too deep.”

“We’ve been deeper before and walked away,” Ben reasoned.

No one spoke.

“The woman. What if she figures the noises under the carpet were rats?” Ben asked. “Maybe she sends a pest guy down there.”

Matt was white-knuckling the kitchen sink, staring out the window at the training yard. “Some dumbass rat guy’s not going to know anybody else was down there messing with the electrics. He’ll be looking for rats, not bugs.”

“‘Rats, not bugs,’” Engo laughed. “That’s funny.”

“What if she doesn’t figure it’s rats,” Ben said. “We hit the jewelry store in three weeks, and she remembers the noises she heard under the floor. Reads about the fabric-store fire in the papers. Sees it was the same night she heard the noises.”

“So we wait a month,” Matt said.

“We can’t go ahead,” Ben insisted. “A job this size has got to be perfec—”

“I said we’re doing it!” Matt grabbed a mug off the counter, gripped its rim and handle and sides like a baseball. Like a grenade. “You got a hearing problem I don’t know about, Benji?”

He didn’t answer. No one did.

In the end, Ben just shrugged, because he was tired and he didn’t need a coffee mug to the temple right then.

And what did he care, anyway? They were all going to jail, whether it was a month from now or sooner.

***

He was staring into his plate of eggs at Jimmy’s when she came in. Ben’s hands were still shaking. Had been all morning. But he couldn’t figure out if it was last night’s near-miss under the jewelry store or The Silence, as he’d come to think of it. The great big Nothing-At-All that had happened since he’d left a handwritten letter on the windshield of a car belonging to a homicide detective from the South Bronx.

Eighteen days. Not a phone call. Not an email. Not a sound.

He poked his eggs with his fork and listened without really listening to the people bustling in and out of the diner, their moaning about the heat. A Ferris wheel of possibilities was turning in his head, each carriage a different explanation for why nothing had happened since the letter. Maybe the guy had figured it was a prank. Maybe the wind had swept the envelope off his car. Maybe his girlfriend and her kid going missing had fucked Ben’s brain up so bad that he’d imagined the whole damn thing—choosing the detective, writing the letter, putting it on his car. He’d been so jacked, walking there and placing the envelope under the windshield wiper, that he barely remembered doing it.

Maybe it was much worse than any of those things.

Maybe Engo or Jakey or Matt had followed him the day he left the letter. Maybe they’d taken it off the windshield. Read it.

Maybe they knew.

His fork was doing Morse code on the edge of his plate. One of Jimmy’s guys banged a fry basket into the hot oil and the fork leaped clean out of Ben’s hand. He had to stop thinking about it. He looked at Jimmy’s terrible clumsy handwriting on the greasy whiteboards above the fry station and picked off items and tried to think about them instead. About salad. About burgers. About soup.

Ben stared at his eggs.

The woman had to say his name a couple of times before he heard her.

“Benjamin Haig?”

He looked over. The woman was sitting on the stool next to his, her hand on the countertop near a steaming coffee. He had no idea how long she’d been sitting there, got the feeling that it might have been a while. Her bobbed blond hair was slicked behind her ears and she was watching him through navy-blue reading glasses. His rattled brain took down some things about her. She was beautiful. She was expensively dressed. She was a stranger. That was all he got.

When the woman knew she had his attention, she unfolded the newspaper on the counter in front of her and set about scanning the headlines.

“I’m here about the letter,” she said.

Click below to pre-order your copy of Devil’s Kitchen, available June 4th, 2024!

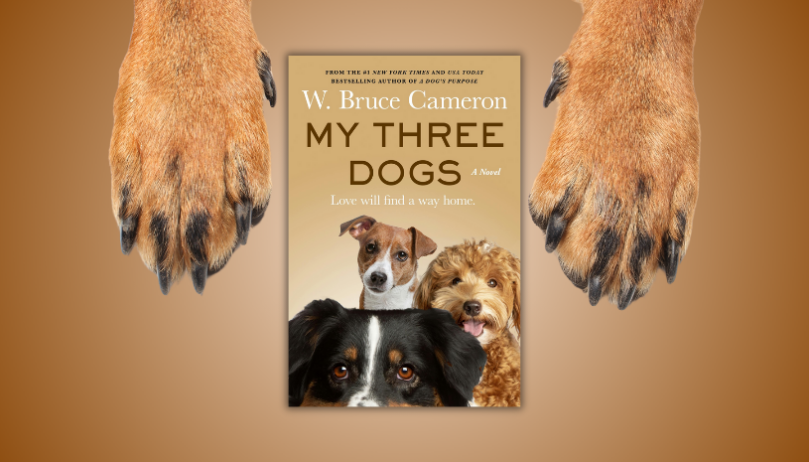

My Three Dogs is a charming and heartfelt new novel from the #1 bestselling author of A Dog’s Purpose, about humankind’s best, most loyal friends, and a wonderful adventure of love and finding home.

My Three Dogs is a charming and heartfelt new novel from the #1 bestselling author of A Dog’s Purpose, about humankind’s best, most loyal friends, and a wonderful adventure of love and finding home.