The Sword’s Elegy is the third book in a new epic fantasy trilogy from successful self-published author Brian D. Anderson, perfect for fans of The Wheel of Time and The Sword of Truth.

The Sword’s Elegy is the third book in a new epic fantasy trilogy from successful self-published author Brian D. Anderson, perfect for fans of The Wheel of Time and The Sword of Truth.

The doom of humankind has at last been realized. Belkar’s prison is broken and his army is on the move. The nations of Lamoria, unaware of the greater danger, look to repel the aggression of Ralmarstad.

Mariyah and Lem, certain that only the magic of the Bards can save them, desperately search for that lost knowledge. But friends and allies are what they need to complete their task. And they are in short supply. For, while peril often brings out the best in us, it also brings out the worst.

In the end, it is not great power, terrible armies, or mighty warriors who will influence the course of fate. But two lovers and the unbreakable bond they share. All questions are answered. All mysteries revealed. And even Belkar will learn that fate, once tempted, cannot be denied.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of The Sword’s Elegy by Brian D. Anderson, on sale 11/1/22.

2

Lem’s heart froze. “Are you sure?”

The young girl carrying a bundle of cloth across her back nodded somberly. “Gothmora too. Fifty thousand soldiers is what I hear. And more are coming, if what my uncle told me is right.”

“Is your uncle a soldier?” Mariyah asked.

The girl shook her head. “Cloth merchant. But he was in Ubania when the Ralmarstads landed. Had to leave an entire shipment behind, otherwise he’d have been trapped there.”

Lem and Mariyah exchanged worried glances. “I’m sure Loria’s all right,” Lem said.

Mariyah closed her eyes and nodded slowly. “Of course. I am too.”

Lem turned his attention back to the girl. “Thank you. I hope your uncle recovers from his bad fortune.”

The girl shrugged. “He’s got plenty of gold. Maybe now he’ll retire.”

Lem smiled, then waited until she continued on her way before speaking to Mariyah. “Do you want to go to Ubania?”

“No,” Mariyah replied. “If Loria escaped, she would go to the enclave.”

Lem looked out on the road ahead, leading to Throm. He now regretted the detour. A simple inquiry would have told them what had happened. Had they not spotted one hun- dred or so Lytonian soldiers camped along the roadside the previous night, it would not have occurred to him to ask the young lady for news.

“Before you say a word,” Mariyah added, “we’re not turning back. I insist on seeing Shemi. And you need your balisari.”

Lem doubted Shemi was still in Throm. Travil had told him that should war break out, he intended to take Shemi to Gath, where he owned a small cabin deep in the forest where no one was likely to find them. Somewhere they could be alone, where Shemi could wander the woods in peace and heal from the pain of being parted from Lem. It had taken no small measure of convincing to get his uncle to agree. But Lem needed to know he was safe. Travil had left detailed instructions on how to find them, a condition Shemi had insisted upon, and he’d made Lem recite the directions from memory. Of course, going to Gath would bring them closer to Ralmarstad. Under the circumstances, Travil might de- cide it was better to go elsewhere. If so, Shemi would be sure to leave word on how to find them. And from the conver- sations he’d had with Mariyah, she would not do anything else until she at least knew where Shemi was. They had gone through so much together, and it was clear she felt enormous guilt for bringing him with her.

Shemi aside, Lem was grateful to be recovering his balisari. It was all he had left of home . . . and his mother. It didn’t seem real that the instrument he had plucked away at as a child, thrown over his back countless times on his way to a festival or celebration, held more value than everything in Vylari. Then again, had people known that he was playing a balisari crafted by power of the ancient bards and used for the creation of magic, likely they’d have taken it and cast it into the Sunflow.

Mariyah was eager to see if they could combine their powers and was excited to learn that he’d been given a book containing Bard magic. But Lem remained wary. There was nothing to guide them; no indication as to the purpose be- hind the spells. While true that Bard magic was said to be benign, there was no guarantee of this. It was Bard magic that had enabled Belkar to come to power. Lem and Mari- yah could inadvertently cause tremendous harm. Of course, this was assuming they could combine their power in the first place. He’d seen Mariyah cast a few simple spells since their escape from Belkar’s clutches, and while each had its own unique tempo and timbre, the mechanics of them were a mystery. It was like trying to learn to weave a quilt with a ball of yarn and no instruction or even an example to go by. Given time, Lem was sure he could figure it out. But time was not a thing they had in abundance. It could very well come down to making random attempts, hoping to stumble onto something useful. But for the time being, he thought it best to wait until all other options were exhausted—not that they had many.

Mariyah passed the reins over to Lem. “If Ralmarstad has landed armies in Ubania and Gothmora, they’ll move on the other city states first.”

“Will they fight back?”

Mariyah shrugged. “I couldn’t say. But I doubt it. None have more than city guards to mount a defense with. A few Thaumas might be willing to fight if they find themselves trapped. Not enough to stop them, though.”

Lem urged the wagon forward with a snap of his wrist and a click of the tongue. “With the Archbishop in exile, there’s nothing standing in their way, then.” He noticed Mariyah had lowered her head, and her hands were clasped tightly in her lap. “Still thinking about Loria?”

“No.” She turned her head to give Lem a dire look. “Belkar. If Ralmarstad is attacking, it means he’s free.”

Lem felt a chill race through his body. “So he’s coming?”

“I don’t know. Not yet I think. If he was, I would . . . feel it.”

“How long do you think we have?”

She shook her head, returning her gaze downward. “I don’t know. If I understood the magic that imprisoned him better, I might be able to say. I know enough to tell you that breaking free would have left him weak. He’ll need time to recover, and more to bring his army through the breech.” She slammed her foot into the floorboards. “I’m so stupid!”

Lem was taken aback by her sudden outburst. “What’s wrong?”

“We should never have left the mountain.”

“Why not?”

Mariyah’s face was flush and her jaw tight. But she did not reply. Why should they have stayed? Surely Belkar would have killed them both if they had. He wanted to press her, but knew enough not to. When Mariyah was angry, it was better to wait until she had time to calm down, and particu- larly when she was angry with herself. Hot-blooded was how her mother frequently described her. But Lem had detected a change. It was subtle, but noticeable nonetheless. Between Lem and Mariyah, Mariyah had always been the more fo- cused and capable. And while her temper did occasionally get her in trouble, more often than not she was the one her friends would look to when disagreements arose. It was the same with her family. A perfect blend of her father’s tenacity and her mother’s insight and empathy. Certainly she had matured. So had he. But the change in Mariyah was some- how deeper; more profound. It was as if she were in constant conflict with herself, the interlocutor a hidden voice with which she did not always agree.

It took Mariyah more than an hour to break from her melancholy.

“I was thinking about what to do when this is all over,” Mariyah remarked, reaching over to slip her arm around Lem.

“I think I’d like to travel with you while you play.”

Lem leaned his head against hers. “You don’t want to go home?”

“Long enough to see my parents,” she replied. “But I don’t think I could go back. It wouldn’t be the same.”

“I think your mother would tie you to a tree before she’d let you go again.”

“She’ll understand. It’s Father I worry about.” She leaned up and cocked her head at Lem. “Do you really want to go home?”

Lem thought for a moment. “I don’t know. When I left, I thought that I’d never be able to return, even if I tried. After all, the barrier would stop me.”

“I can get us past the barrier.”

“If I did want to go back to Vylari . . .” He paused until she met his gaze. “Would you come with me?”

Mariyah laughed softly and gave him a gentle kiss. “Of course I would. But do you think you can go back?” she asked.

Her smile remained, but there was a touch of sadness in her voice.

“I . . . I don’t know. Now that you’re here, I don’t really care where I am. Shemi has Travil, so he doesn’t need me.”

“I think Shemi would have something to say about that.” “Shemi deserves a life of his own,” Lem said.

“And you don’t think he could have one with you there?” Lem felt a tightness in his gut. “It wouldn’t be me. Not the me he knew. I kept him with me far longer than I should

have.”

“Neither of us are the same as we were when we left,” Mariyah said. “Vylari is a world within a world. Unchanging. Cut off. Like a flower sealed in glass, unable to grow, unable to die. Unable to spread its pollen and pass on its beauty.”

Lem had never thought of it that way. For him, Vylari was the embodiment of what life should be. The people were kind, for the most part, and took great pleasure in the sim- ple things that invariably passed unheeded in Lamoria—like the distinct aroma of wet grass after a light rain or the lonely call of an owl at dusk. But Mariyah was right to say it was unchanging. Still, Lem had no desire to see it change. That Vylari was at that very moment exactly as it was the day he crossed the barrier was a great comfort.

Mariyah climbed into the back, rummaged around for a few minutes, and then returned holding a map of Lamoria she had purchased a few days prior.

“If we hurry,” she said, running her finger over the paper, “we might make it to the enclave ahead of Loria.”

Though he had suggested it, Lem was unsure how wise it was going there. He was a Bard. A real Bard. Despite Mariyah’s assurances that the Thaumas would not try to harm him, Lem could tell this was weighing on her mind also. He didn’t want her to be forced into a confrontation. And should the Thaumas threaten him, that was precisely what would happen.

“I know the fastest routes through Syleria,” he said.

Mariyah looked up from the map and smiled. “Sorry. I forget sometimes how well traveled you are. This was my first trip away from Ubania.” She averted her eyes and folded the map. “It’s strange. Vylari is our home. I can still feel it waiting for us. But Ubania . . . the manor, even my room . . . That’s home too.”

Lem gave her a sideways look. “Ubania?”

Mariyah nodded. “Yes. I know it’s hard to believe, but it’s special to me in a way not even my family’s vineyard is. It’s where I found out who I really am. What my potential is as a person.”

“I don’t understand,” Lem said. “They imprisoned you there. Forced you to serve against your will.” Even though Lady Camdon had freed her, it didn’t change the manner in which Mariyah had been brought. Or that other innocent people in Ubania were not so fortunate as to have someone like Lady Camdon pay for their indenture.

“I know. But I was also forced to face my fears . . . and conquer them.”

“You dealt with it better than I would have,” he said. She tossed the map into the back and leaned her head on his shoulder. “I think you might surprise yourself.” She lifted her eyes to his. “Do you think I’ve really changed?”

Lem kissed her forehead. “For the better.”

Mariyah straightened and frowned. “I mean it, Lem.

Have I changed to you?”

Lem sighed. “I’m not sure how to answer.” “Honestly.”

“That’s not what I mean. I don’t know how to answer you.

I’m not good with words like you are.” “Then do your best,” she said.

Lem thought for a long, careful moment. “You are the same person I’ve always known. But you’re also a person I’ve never known. I see you and think about how much you’ve had to endure to survive. When you told me about the men you killed just before Belkar captured you, I was shocked . . . but then, I wasn’t. Or how you are able to tease out secrets from the Ubanian nobles and use the information as lever- age. My mind tells me that I shouldn’t be surprised. How many times did you catch people trying to swindle your fa- ther? You’ve always been able to read the intentions of oth- ers.” He paused, searching for the words to express what he was thinking. “My mother told me just before she died that one day you would become a woman. That I shouldn’t expect you to be a little girl forever. If I did, I would never be able to love you the way you needed to be loved, and one day, I’d wake up and a stranger would be looking back at me. I didn’t understand what she meant at the time. But I think I do now.”

Lem reached out and took her hand. “I want to be the man you need me to be. And the man you want me to be. When I was the Blade of Kylor, I thought I could only be one and not the other. That I was being who you needed so that you could be free. But doing so meant I could never be who you wanted.”

“I hope you know that’s not true,” she said.

“I do. That’s why I understand what my mother meant. The girl I knew will always be a part of you. But the woman you’ve become is so much more. She is stronger, smarter, more resourceful, kinder and yet harsher. Her anger is greater and yet tempered with far more self-control. She has seen things that would have sent the young girl you were weeping into a corner.”

“Sometimes I did,” she said, smiling and wiping her eyes free of unexpected tears.

“I suppose what I’m trying to say is that I wasn’t there to watch you become the woman you are. This is my first time meeting her.”

“And now that you’ve met me?” More tears fell, though not tears of sorrow.

“I still feel the way I did on the first day we met: lucky.”

Mariyah snatched the reins away and pulled the wagon to an abrupt halt, leaving Lem looking startled. But before he could ask what was wrong, she pulled him in for a long, crushing kiss. The sudden show of affection took Lem aback for a moment. But he quickly recovered and returned the kiss fully.

When their lips parted, he smiled at her. “What was that for?”

“Being lucky,” she said.

They continued for a time, the mood one of optimism and contentment. It was in the moments their hearts were closest that the danger approaching from all sides felt dis- tant. It was in these brief respites that Lem found himself able to think about the future in a way that did not feel as if he were lying to himself.

About four miles from Throm, they saw a row of conical tents lining either side of the road. Several Lytonian soldiers were stopping wagons and pedestrians, with some turning back, others continuing on their way.

A young woman in civilian attire approached their wagon, wearing a serious expression.

“Are you residents?” she asked.

“I am,” Lem replied. “What’s happening here?”

“Then you’ll need to provide your name and address to the sergeant before you’re allowed to cross the town border,” she said, ignoring Lem’s question.

Mariyah leaned across to say something, but Lem’s hand on her arm had her reluctantly holding her tongue.

“Best not to cause a stir,” Lem said. “Let’s just get my things, see if Shemi is still here, and go.”

It was hard for Mariyah to let unwarranted rudeness go unanswered. That much had not changed.

The sergeant up ahead did not find his name on the town registry. Not surprising, given that he rented the apartment on a monthly basis. Fortunately one of the city guards who was aiding the soldiers recognized him.

“Why all the commotion?” Lem asked.

The guard looked at him incredulously. “You can’t be se- rious? Ralmarstad is coming. Every town between here and the capital is evacuating.”

“Do you know my uncle—Shemi?” Lem asked. When the guard didn’t show any sign of recognition, he added: “He’d be with Travil.”

“Oh, Shemi. Yeah. I think I did. Can’t say when, though. So much going on and all. Probably gone by now. Most everybody is. Only a few stragglers left. And folks like you just returning.”

“Where are people going?” Mariyah asked.

“East, for the most part. I hear the whole Lytonian army is mustering. The Sylerians too. These chaps were sent to see that everyone gets out in time. Nowhere near the sea is safe.” He blew out a breath. “Guess I’ll be hanging up my guard uniform soon and joining in.”

The guard handed Lem a temporary pass, should he be stopped and questioned, and waved them through.

“You think they could really be coming so soon?” Lem asked.

Mariyah shrugged. “What little I know about warfare is from books. But it would take a long time to muster an army large enough to attack Lytonia.”

Lem considered this as the wagon slowly trundled forward. She was right; a sizable enough force would take time to assemble. Not only that but they would need the ships to transport them. He’d assumed that Ralmarstad would at- tack Garmathia and continue west to Xancartha.

“There are some small islands northwest of Lobin,” Lem said. “You think they could have launched the attack from there?”

“Couldn’t say. I guess it doesn’t really matter. So long as we stay ahead of them.”

Lem was reluctant to correct her. “But if they launched from the islands, it means they could land anywhere. For all we know, they’re on their way here as we speak.”

She took his point. “Then we need to get rid of the wagon.” Once in town, they found that the guard had been correct. Only a few people were about, mostly shopkeepers and a few residents furiously loading wagons in a mad scramble to evacuate. To his dismay, the apartment he and Shemi had rented was empty and Judd’s home was abandoned. They hurried to where Travil had told him he lived—a small house with a workshop in the rear at the south end of town. But it was empty too.

Mariyah was deeply disappointed not to have caught Shemi in time. “You think he took your things with him?”

Losing his balisari was a blow. Lem forced an unconvincing smile. “It doesn’t matter. I can get another one. In truth, it was the only thing I had of any worth. The rest was just clothes.”

Mariyah placed a hand on his shoulder. “I’m sure he has it.” She could tell he was upset. She could always tell what he was feeling and knew he was being intentionally dismissive to hide the pain of the loss. Even were it not his mother’s, a balisari would be difficult to find.

It was getting late and the inn was closed, so they decided to sleep on the floor of his old apartment. Lem scrounged up a loaf of bread and a bottle of wine from a shoemaker who was just readying to depart and, along with some dried figs and jerky from their provisions, they had a quiet meal on the balcony.

As the sun set, a strange silence fell over Throm, broken intermittently by unintelligible shouts and the smashing of glass. It was nothing like the calm one found away from the cities and towns. The blackness of night in the forest was teeming with life and vitality, even if it was hidden from sight. This was more akin to death. Throm was a corpse splayed out on the field, the carrion feeders circling in anticipation of a meal. Darkness without spirit.

“It feels like the end,” Mariyah remarked solemnly.

They had pushed the chairs aside and were seated on a blanket, peering out through the cast iron railing. Neither had touched a bite.

“It is,” Lem said. “At least it’s the end of something.

Though I’m not entirely sure what.”

“Do you ever wish we’d stayed in Vylari?”

Lem lowered his head and tried to imagine the cottage in which he had grown from a boy to a man. The fields and hills he and Shemi had spent countless hours exploring. The banks of the Sunflow River. But it was dulled and out of focus.

“I did in the beginning,” he replied quietly. “But not anymore.” He looked out upon the deserted streets. “We’re a part of this. If we had stayed, Belkar would have found us eventually. At least now we can do something.”

A few times he had considered that had they stayed, Belkar might not have found Vylari at all. He wouldn’t have been searching for it. But it was a foolish notion, and one not worth mentioning out loud.

“I hope we can. And I really will go home, if that’s what you want.”

He took her hand and kissed it. “I know you would. But to be honest, I’ve seen so much. Done so much. I’m nothing like anyone in Vylari, not anymore. Not that I ever was to begin with. But it’s hard to picture myself teaching children and playing the festivals again. I’m just not that person any- more.”

“So you want to stay in Lamoria?”

“I want to stay with you,” he said, grinning to lift the mood. “Maybe we can live on a boat. Or on top of a mountain. Wherever you want.”

“I’m being serious,” she said, though her smile was grow- ing. “When this is over, do you want to go home?”

“That’s just it. I don’t know where home is. Shemi has found where he belongs. But other than being at your side, I don’t know where I do.” He expected her to say something to convince him that he was wrong; that Vylari was still his home. But instead she nodded slowly and shifted to lean against his chest.

“All I know is that I want to see my parents,” Mariyah said, finally sipping her wine. “But I was thinking the same thing. When I picture the people back home, it’s like they’re . . .”

“Innocent.”

“Yes. Exactly. I’m afraid I would somehow corrupt them.”

Lem kissed the top of her head. “I think Vylari could use a bit of corruption.”

Mariyah tilted back to look him in the eye. “Do you really believe that?”

“I’m not sure,” Lem said. “But sooner or later, the world will find them. Sooner is my guess. As it is, they wouldn’t be prepared for it.”

“Maybe that’s a reason to go home,” Mariyah offered. “Get them ready for what’s coming.”

Lem laughed. “Can you see your father selling wine to Lamorians?”

Mariyah drained her glass. “I could see him retiring on the gold his wine would earn.”

They were speaking nonsense, and they both knew it. But it felt good to pretend. The truth was that the people of Vylari would be terrified if faced with the prospect of being ex- posed to the rest of the world. The panic and chaos it would cause was incalculable. But one thing Lem had said was true: whether or not Belkar was defeated, the world would find them eventually.

They picked at their food and finished half the bottle be- fore deciding they’d had enough. Neither was tired, and Lem doubted he would get much sleep that night. Mariyah told him she preferred not to go inside. They were in no danger of rain, and their blankets were thick enough to fight off the cold.

“I’ve never liked an empty house,” she said. “I remember.”

A few months prior to their betrothal, they had gone with Mariyah’s mother to her cousin’s newly built home to help her paint the interior. The furniture had yet to be brought over, and they had laid out blankets in the living room. Both women were up and outside sleeping on the porch before midnight. Lem recalled his relief upon joining them, the house feeling disturbingly like a dead husk—an empty thing where life did not belong.

They settled down as well as could be expected, the warmth of their bodies more than adequate to keep them comfortable.

“Did you hear that?”

Lem was half dozing. Rubbing his eyes, he sat up. A few moments later, the distant but unmistakable call of a horn drifted on the air.

Mariyah rose to her feet and leaned over the railing just as another horn blew. “I think we should go.”

Before Lem could respond, the stomping of feet on the stairs had them rushing inside. Lem grabbed his pack to retrieve his vysix dagger, but Mariyah stopped him.

“You’re never to use that again,” she said, then grinned as she turned to face the door, hands spread wide. “Don’t worry. We’re safe.”

The door flew open, and Lem cursed himself for forgetting to lock it. Mariyah’s hands glowed bright red, casting unnat- ural shadows on the walls and floor.

A stocky man in the brown robe of a monk hurried inside. Seeing Mariyah, he stopped short and raised his hands.

“I’m a friend,” he blurted out, stepping back a pace.

“I know all my friends,” Mariyah said, her tone cold and dangerous. “And I don’t know you.”

“I’m Brother Umar,” he said, slightly out of breath. “I was sent to bring you to Xancartha.”

“Then you can turn around and go back,” Lem said. “I told Rothmore: I’m finished.”

The horn sounded, this time closer.

“Ralmarstad landed in Sansiona,” he said. “They’re heading straight for Throm this very minute.”

Lem and Mariyah exchanged knowing looks.

“Then you’d better run,” Lem said. “And you can tell Rothmore I will never step foot in the Temple again.”

The monk looked anxious, understandable with the Ral- marstad army nearby. “I have your balisari,” he said. “Come with me and I’ll return it to you.”

Lem sniffed. “Keep it. I have another.”

“You’ll give it back now,” Mariyah interjected. A thin ribbon of yellow light sprang from her palm and wrapped around the man’s throat.

His eyes bulged, and a few seconds later he was forced to his knees as he clawed futilely at the spell.

“Mariyah,” Lem said, placing a hand on her shoulder. “It’s not worth the effort.”

“It was your mother’s,” she said. “And I’m certain he’ll be more than happy to give it back. Won’t you?”

The man nodded frenziedly, spitting out what were meant to be words but came out as gargled hisses. When the ribbon vanished, he fell to his side, coughing and wheezing.

“Where is it?” Mariyah demanded.

“I don’t have it here,” the monk managed to choke out. “It’s on a boat, waiting to take us to Malvoria.”

Lem grumbled. If it hadn’t been his mother’s instrument, he’d have left it behind without a second thought. After all, there was a replacement at the college. “Take us there,” he said. “But I’m not getting on the boat. Understood?”

The monk struggled to his feet. “Yes. But we need to hurry. The Ralmarstads are moving swiftly.”

Outside several horses were heard passing at full gallop, and the horn blew once again, this time coming from within the town. The borders had been breached. Likely the Lyto- nian soldiers had abandoned their posts.

Mariyah and Lem snatched up their packs and bolted for the door, the monk on their heels. There was no time for the horses and wagon.

“Through there,” Brother Umar said, pointing across the main avenue to an alley between two shops a few yards farther south.

Lem glanced down the street to see a line of torches round- ing the corner roughly five blocks away. He had no idea how many foes Mariyah could overcome with her magic, but it wasn’t likely to be an entire army.

Brother Umar stopped at the far end and peered out. Lem could hear the stomping of many boots and the clanking of steel, from both behind and ahead. Throm was not a large town, but it was not a road stop either. It would take at least ten minutes to get beyond the town’s edge and several hours to reach the coast on foot. But that would take them in the wrong direction.

A voice called out as they were halfway across the next street. “Stop there!”

Lem could see four soldiers with swords drawn a block off to their right. Straining his eyes against the pale light of a half moon, he could make out the Ralmarstad sigil on their breastplates. Mariyah shoved him toward the promenade and stood in the center of the thoroughfare.

A stiff wind blew the hair from her face, and her eyes burned with a red glow. Lem felt a chill creeping up his spine. It was as if the stories of demon spirits he’d heard as a child had come to life. The flesh of her face and arms turned a slate gray as she clenched her fists tight.

“Come,” she said, her voice sounding at multiple pitches simultaneously. “See what your masters have sent you to find.”

Lem had never heard her speak this way. It was terrifying. “Thaumas!” shouted one of the soldiers.

“No,” she replied, the hint of a smirk twitching at the corner of her mouth. “Something more.”

In a swirling flurry of motion, she swept her arms in a broad circle. Two of the soldiers immediately turned and fled.

They were the first to fall. There was the crunch of steel that sounded like thin glass being stepped on by a heavy boot, followed by a short yelp and a gasp. Blood exploded onto the street, bursting from every orifice. She waited until the two remaining foes were almost upon her before repeat- ing the spell.

Lem nearly emptied his stomach at the sight. Brother Umar could only stare at the scene horror-stricken, hands covering his mouth.

When Mariyah turned to face them, her cheeks, hair, and clothing were drenched in blood. But a quick wave of the hands remedied the situation, and in a flash the blood had evaporated. Her expression was not one of rage but a stone mask that bordered on indifference, as if she’d done nothing more significant than swatting a fly. But upon seeing Lem’s reaction, she gave him a pained look.

“I wish you didn’t have to see that,” Mariyah said.

Lem took a moment to regain his composure. “Why did you do that?”

“So no one will follow,” she replied, then turned to the monk. “Lead on.” It took a hard poke to his arm before he snapped out of his stupor. And when he did, he averted his eyes, clearly afraid.

As they made their way from town, Lem could not get the image out of his mind. He had killed scores of people. And he’d had experience with aggressive magic at the hands of Lady Camdon. But what Mariyah had done . . . she’d crushed the very armor they were wearing until they popped inside it like ripe grapes. She was right that anyone coming across the gruesome scene would be hesitant to follow their trail. But there had to have been another way.

The land between Throm and the shore was thinly wooded, providing little in the way of concealment. In the far distance, an orange glow lit the night sky, and from the direction Lem guessed that Sansiona was burning. Soon Throm would suffer the same fate. Lem felt a pang of regret that the peaceful little town would be reduced to ashes. He had actually thought of asking Mariyah if she would con- sider settling there, or barring that, at least buying a house. After all, it was Travil’s home and would likely have been Shemi’s as well. They would have wanted to visit regardless of where they eventually found themselves.

Brother Umar kept his distance from Mariyah as they wound their way a mile east and parallel to the highway. Occasionally they could hear the shouting of orders and the clatter of steel, but the monk deftly led them clear of the danger. Soon the flames from Sansiona were joined by those of Throm. Lem wondered if everyone was able to get out in time. He hoped so. Those caught by Ralmarstad would be interrogated then possibly killed. It wouldn’t matter that the townsfolk would not know anything of value or that they were not a threat. In the eyes of Ralmarstad, they were her- etics, and that was the only justification needed to perceive someone an enemy.

The light of dawn overcame that of the flames, and lines of black smoke carried with them the stench of death. They were forced into an open field to reach where the boat awaited, along with three hulking clerical guards. Despite their intimidating appearance, their eyes betrayed fear.

“We were about to leave,” a guard wearing a plumed helm said. “Ralmarstad patrols are bound to come this way soon enough.”

The other two were already shoving the small landing craft into the water.

“Where’s Lem’s balisari?” Mariyah demanded.

The monk averted his eyes. “Like I said, it’s waiting on the ship that brought me. I wouldn’t keep it here on shore.”

“Then you can send your guards to retrieve it,” Mariyah said.

“When we leave,” the guard chipped in, his gaze drifting to the direction of Sansiona. “We will not be coming back.”

“Please. Just come with us,” the monk implored. “I told you no,” Lem said. “And I meant it.”

The guard grabbed the monk’s arm. “If you’re coming, now is the time.”

Umar gave Lem a final beseeching look, then, receiving his answer through Lem’s silence, hurried into the boat.

Lem could see that Mariyah was fuming at the loss of the balisari, not to mention a wasted trip. But he knew that if they boarded the ship, the monk might attempt to hold them captive. And considering what Mariyah had done, he wasn’t about to put her into a position where she felt trapped. Not to say he feared they could not deal with the situation; but hav- ing witnessed what her powers could do, the slaughter of an entire ship’s crew was not worth recovering his instrument.

“We’ll get it back,” she said, taking his arm as they watched the guards rowing away as fast as they could manage.

“I know.”

The trouble to which Rothmore had gone to lure him to Xancartha suggested that he would not give up trying. But with war sweeping across Lamoria, Lem was confident he could stay well away. Ralmarstad would move against the holy city with the bulk of their army, and he was not about to get caught up in a siege. The other balisari would have to suffice. If they lived to see the end of this, he’d worry about it then.

“We should go to the enclave,” Mariyah said. “If there’s a way to stop Belkar, that’s where we’ll find it.”

Lem nodded, eyes fixed on the horizon. At that moment, he felt small and quite insignificant—a state of being he hadn’t experienced since before becoming the Blade of Ky- lor. He had spent much of his time in Lamoria protecting the people he loved. Now, Shemi had Travil. And Mariyah . . . if there were a living being who could protect themselves better, he couldn’t imagine who it was. What good was he? Even if he still had his balisari, or acquired a new one, what then? What could he possibly learn that could help them fight someone like Belkar?

He would have to content himself with standing beside Mariyah, useless and impotent, while she made a stand against an immortal being whose power could enslave an entire world. He felt her hand slip into his. The impulse to go home had never been stronger.

It will pass, he thought. But that was a lie, and he knew it.

Copyright © 2022 from Brian D. Anderson

Pre-Order The Sword’s Elegy Here:

Dune seems really cool:

Dune seems really cool: No, really. Dune is the coolest and you’ll throw yourself into the maw of a sandworm if you don’t get more immediately:

No, really. Dune is the coolest and you’ll throw yourself into the maw of a sandworm if you don’t get more immediately: You love crazy space monsters:

You love crazy space monsters: You love dudes fighting in suits in space:

You love dudes fighting in suits in space: You love PEW PEW PEW space battles:

You love PEW PEW PEW space battles: You love space politics:

You love space politics: No, seriously, you LIVE FOR space politics:

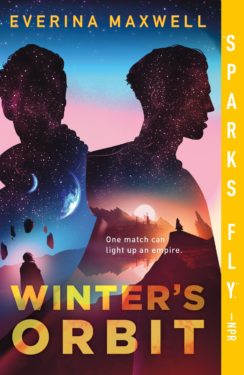

No, seriously, you LIVE FOR space politics: You love space politics, but not as much as you love love.

You love space politics, but not as much as you love love.