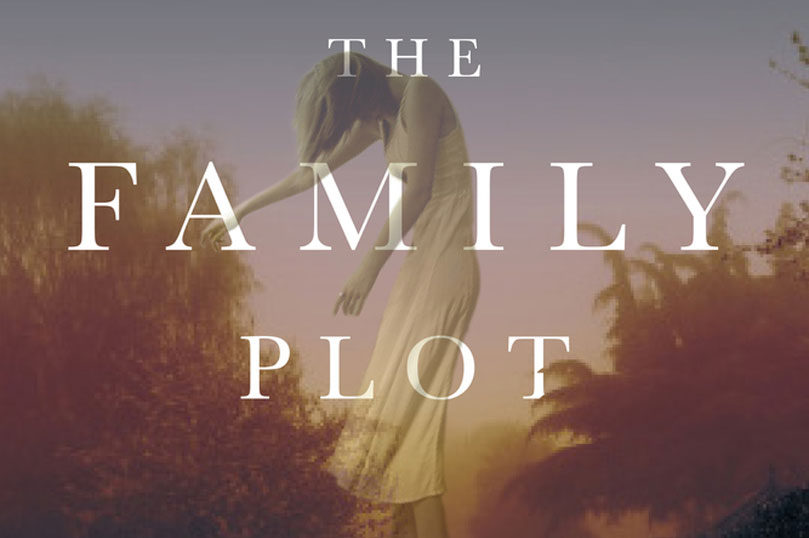

Chuck Dutton built Music City Salvage with patience and expertise, stripping historic properties and reselling their bones. Inventory is running low, so he’s thrilled when Augusta Withrow appears in his office offering salvage rights to her entire property. This could be a gold mine, so he assigns his daughter Dahlia to personally oversee the project.

Chuck Dutton built Music City Salvage with patience and expertise, stripping historic properties and reselling their bones. Inventory is running low, so he’s thrilled when Augusta Withrow appears in his office offering salvage rights to her entire property. This could be a gold mine, so he assigns his daughter Dahlia to personally oversee the project.

The crew finds a handful of surprises right away. Firstly, the place is in unexpectedly good shape. And then there’s the cemetery, about thirty fallen and overgrown graves dating to the early 1900s, Augusta insists that the cemetery is just a fake, a Halloween prank, so the city gives the go-ahead, the bulldozer revs up, and it turns up human remains. Augusta says she doesn’t know whose body it is or how many others might be present and refuses to answer any more questions. Then she stops answering the phone.

But Dahlia’s concerns about the corpse and Augusta’s disappearance are overshadowed when she begins to realize that she and her crew are not alone, and they’re not welcome at the Withrow estate. They have no idea how much danger they’re in, but they’re starting to get an idea. On the crew’s third night in the house, a storm shuts down the only road to the property. The power goes out. Cell signals are iffy. There’s nowhere to go and no one Dahlia can call for help, even if anyone would believe that she and her crew are being stalked by a murderous phantom. Something at the Withrow mansion is angry and lost, and this is its last chance to raise hell before the house is gone forever. And it seems to be seeking permanent company.

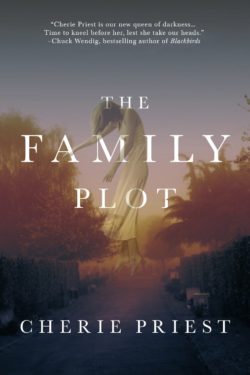

The Family Plot—available September 20th—is a haunted house story for the ages-atmospheric, scary, and strange, with a modern gothic sensibility to keep it fresh and interesting-from Cherie Priest, a modern master of supernatural fiction. Please enjoy this excerpt.

1

“YEAH, SEND HER on back. She has an appointment.”

Chuck Dutton set aside the walkie-talkie and made a token effort to tidy his desk, in case Augusta Evelyn Sophia Withrow expected to speak with a goddamn professional. The owner and manager of Music City Salvage was every inch a goddamn professional, but he couldn’t prove it by his office—which was littered with rusting light fixtures, crumbling bricks and broken statuary, old books covered in mildew, stray tools that should’ve been packed away, and a thousand assorted items that he was absolutely going to restore to life or toss one of these days when he got the time. His office was the company lint trap, and it was no one’s fault but his own.

He successfully rearranged a stack of old license plates and stuffed all his pens into an I LOVE MY MASTIFF mug, just in time for his visitor to appear. She arrived in a faint cloud of expensive perfume: a tall, thin lady of a certain age and a certain pedigree. Her hair was silver and her dress was blue linen, something with a fancy label at the neck, unless Chuck missed his guess. Her handbag was large, square, and black—more of an attaché case than a purse.

She stood in the doorway, assessing the mess; then she bobbed her head, shrugged, and stepped over a nested stack of vintage oil cans that Chuck kept meaning to relocate.

Chuck darted out from behind his desk, hand extended for a greeting shake. “Kindly ignore the clutter, ma’am—like myself, this office is a work in progress. I’m Charles Dutton. We spoke on the phone, before you met with James.”

“Yes, of course. It’s a pleasure.” She accepted his handshake, and, without giving him a chance to offer her a seat, she drew up the nearest chair—a Naugahyde number that had once sat in a mid-century dentist’s lobby. “Thank you for seeing me. I’m sure you’re very busy.”

Chuck retreated to his original position, sat down, and leaned forward on his elbows. “Anytime, anytime,” he said cheerily. “Projects like yours are what keep us busy.”

“Good. Because one way or another, that old house is coming down. It can’t be saved, or at least, I don’t plan to save it. But there’s plenty on the property worth keeping—as James saw firsthand last week.”

“Yeah, he couldn’t shut up about it. But this was your family home, wasn’t it?” He already knew the answer. He’d looked it up online.

“That’s correct. My great grandfather built the main house in 1882. He gave it to my grandparents as a wedding present.”

“And none of the other Withrows are interested in preserving it?”

“There are no other Withrows,” she informed him. “I’m the last of them, and I don’t want it. On the fifteenth of this month, the house will be demolished. By the first of November, all other remaining structures will be razed, and the property will be donated to the battlefield park. The paperwork is already filed.”

“Still, it seems like a shame.”

“Spoken like a man who never lived there,” Ms. Withrow said, not quite under her breath. Then, more directly, “You mustn’t cry for the Withrow house, Mr. Dutton. It’s a miserable, drafty, oppressive old place with nothing but architectural details to recommend it. James made notes and took photos, but I have a few more, left over from the assessment when I inherited it last spring. If you’d care to take a look at them.”

“I’d love to. He said you two talked numbers. I trust his judgment, but my finance guy balked when he heard forty grand, so I’m happy to see more of the details. I hear you’ve got imported marble fireplace inlays, stained glass, wainscoting…”

In fact, Barry the Finance Guy had not balked; he’d put his foot down with a hard-ass no. The company was owed a small fortune in outstanding invoices, as least two of which were headed for court. Music City Salvage barely had enough cash on hand to keep the lights running and cover payroll—and if a windfall didn’t come along soon, they’d have to pick between them. There was absolutely no stray money for sweetheart deals on old estates.

Period. End of story.

Still, when Augusta Withrow unfastened her bag to withdraw a large folder, Chuck eagerly accepted it. She said, “As for the fireplaces, only two have Carrera inlays. The other five surrounds are tile, but all seven mantels are rosewood, and, as you can see, the grand staircase is chestnut.”

“Mm … chestnut…” He opened the folder and ran his finger over the top photo. It showed a staircase that was very grand indeed, with a ninety-degree bend and a platform, plus sweeping rails that terminated in graceful coils. He positively leered. These pictures were a hell of a lot better than the ones James had snapped on his phone.

“I’m told that American chestnut is extinct now.”

“Since the thirties,” he agreed. “It’s strong as oak at half the weight, and pretty as can be. Woodworkers love that stuff. It’s worth … well. It’s very desirable, to the right kind of craftsman. I don’t often see it in stairs, but I’ll take it wherever I can get it.”

“Then I should mention the barn, too. It’s falling down, but I’m fairly certain it’s made from the same wood.”

“Mm.” Chuck’s eyes were full of rust lust and dollar signs. He kept them fixed upon the photos so Ms. Withrow couldn’t see the greed and raise her asking price even further out of reach.

After the staircase, he found a shot of a large fireplace. It had a double-wide front, with a pair of ladies on either side—their poses mirroring one another in white and gray marble. He spied a few thin cracks, but nothing unexpected. All in all, the condition was better than good. He looked up. “James said something about a carriage house. Is that chestnut, too?”

“Only stone, I’m afraid. It has the original copper roof, but it’s all gone green now. You know how it is—the weather gets to everything, eventually.”

He glanced up in surprise. “No one’s stripped it? No one sold it for scrap?”

“I don’t know what kind of neighborhood you think we’re talking about, Mr. Dutton, but…”

“No, no. I didn’t mean it like that.” He shook his head and returned his attention to the folder. “I’ve been to Lookout Mountain before. I know it’s a nice place. I wasn’t trying to imply it was all et-up with meth heads, or anything like that. It’s just something that happens. Over the years the metal goes manky, so people swap it out for cedar or asphalt shingles.”

She didn’t reply for long enough that he wondered what her silence meant.

Finally, she said, “You won’t find any meth heads, no. But the house is just barely on the mountain proper. It’s down toward the base, and some of the nearby neighborhoods are not as savory today as they were a hundred years ago.”

“At the foot … you mean down by the Incline station?”

“At the edge of Saint Elmo—that’s right.”

Chuck frowned. “I know that place; it’s a historic district. Do you have the city’s permission to bulldoze the property?”

“It’s near Saint Elmo, not in it. I don’t need the historic office’s permission, and I assure you, all the appropriate legal steps have been taken. Now, did I mention that the floors are heart of pine, over an inch thick? Except in the kitchen, where they were replaced back in the sixties. My uncle was a very thorough man, with an unfortunate fondness for linoleum.”

“A full inch of pine? Lady, you’re speaking my language,” he said, and immediately felt silly for it.

She grinned, unperturbed by his informality, and pleased to have redirected his attention. “Then you’ll love this part, too: No one’s been inside the barn or carriage house since before I was born. My grandfather boarded both of them up, and declared them off-limits. God only knows what you’ll find once you get the doors open.”

Chuck didn’t dare speculate about her age—not out loud—so he asked questions instead. “Not even a groundskeeper’s been inside? No maintenance people? Burglars?”

“I won’t vouch for the delinquent youths of outer Chattanooga, but barring some unknown vandalism … no. The house is isolated, and the property can be tricky to reach. You might need to throw down a gravel drive for heavy equipment or trailers. I assume you’ll want to take the colonnades? The portico?”

He sorted through more promising photos.

Four columns held up the side porch … he wondered if they were wood, or carved limestone. They weren’t pre-war, but if they were stone, they were worth thousands. If they were only wood, they were still worth thousands, but not as many. He said, “I want to take it all.”

“Then you’ll need a forklift, at least.”

“Good thing I’ve got one. Now, in these pictures, the house is still furnished. I assume all that’s been cleared out by now?”

“Some of it. Some remains, but I won’t kid you about its value. What’s left is too cheap or too broken to pique the appraisers’ interest. You can have it, if you like. I know your representative said you preferred to work piecemeal on projects like this, but my offer is all-inclusive. I don’t have the time or energy to go through the place and put a price tag on every damn thing, if you’ll pardon me for saying so. Anything, anywhere, on the four acres that make up the estate is yours for a check and a signature.”

Yeah, but she wanted that check made out for forty thousand dollars.

It was the most Chuck had ever paid out for a salvage opportunity, by a long shot—and he was still waiting for Nashville Erections to come collect (and pay for) a haul they’d reserved three months ago. It probably served him right for tying up twenty grand in a company named for somebody’s dick, but he knew they were good for it. Eventually. And T&H Construction still owed him for another thirteen grand’s worth of room dividers, bay windows, and a turn-of-the-century door with sidelights and surrounds. Chuck had graciously let them take that batch on credit and a handshake, so it wasn’t even on the floor anymore.

Because sometimes, Chuck was an idiot.

All right then, fine. Sometimes, Chuck was an idiot. But this was the haul of a lifetime, and it could skyrocket the company back into the black within a couple of months.

Or it could be the nail in its coffin in a couple of weeks.

But what a nail.

Cash was low—perilously low—but the stock at Music City Salvage was stagnant. Pickers hadn’t brought in anything interesting in months, and a haul like the Withrow estate would be something worth advertising … a landmark Southern estate, relatively untouched for generations. He could take out a full page in the paper. They’d have customers out the door, rain or shine; they’d come from hundreds of miles around. It’d happened before, but not lately.

The pictures sprawled across his desk, glossy and bright.

Ms. Withrow’s offer wasn’t too good to be true, but it felt too good to be true, and he couldn’t put his finger on why. He was dying to whip out his checkbook and shout, “Shut up and take my money!” But something held him back … something besides the fact that he didn’t actually have enough dough sitting in the corporate account right that moment. In order to sufficiently fill ’er up, he’d have to take money against a credit card. Or two. Or all of them.

It’d be the biggest gamble of his life.

He looked up from the photos, at the woman who sat with her legs crossed just below the knee. She’d scarcely moved since she sat down. She did not look tense, or sinister, or deceitful. She looked like a fancy old lady with good taste who had one last piece of business to take care of before she retired to Florida or wherever fancy old ladies go when they’re finished with Tennessee.

“Do you have any questions?” she gently prompted.

He closed the folder and rested his hands on top of it. “Just one, I guess. Why me? I know at least two salvage crews in Chattanooga who’d be thrilled by a haul this size. Why come all the way out to Nashville?”

“It’s only a couple of hours’ drive, Mr. Dutton—it’s not the Oregon Trail. But since you asked, I visited them both first. Out of pure convenience, let me be clear—I don’t mean to imply you’re third string, or anything of the sort,” she said smoothly, that highbred accent purring. “Scenic Salvage is closing this year; the owner is retiring, and she declined to pursue my offer. As for Antique Excavations … well. Let’s be honest. They don’t have the supplies or the manpower for this job. They were, at least, direct enough to confess it.”

“Judy Hanks told you no?”

“She’s the one who suggested I try you. I understand you know one another.”

They did, but it wasn’t entirely friendly. He didn’t really like her, and as far as he knew, the feeling was mutual. “Sure. I know her.”

“She said you were an ass, but you ran a competent ship—and you’d have the resources to take care of an estate this size.”

Ah. That was more like it. “Not a good ship?”

Augusta Withrow withdrew another folder from her bag. “You should settle for ‘competent.’ It’s high praise, coming from her. High enough that I’ve already arranged the paperwork, based on the details James and I discussed—and I’ve brought it with me. None of this faxing or e-mailing nonsense. I prefer real ink to dry on real paper. I find it reassuring. So, Mr. Dutton?”

“Ms. Withrow,” he stalled.

“Going once, going twice—forty thousand dollars, and you can pick over the remains of my family estate. Do we have a deal?”

He swallowed. He felt the fat stack of pictures beneath his hands. Forty thousand dollars was a lot of money, but the Withrow house was a gold mine. Maybe even a platinum mine, once he got that carriage house open. There was literally no telling what might be inside, if it’d been closed up for what … seventy years? Eighty?

But, but, but.

But the company budget was so tight, it squeaked. But the stock was getting stale. But Barry would kill him, if for no other reason than if it didn’t work … he’d probably be out of a job. For that matter, they’d all be out of a job. The business would have to run on fumes until the Withrow estate started to sell. Paychecks might bounce. Lights might dim. Doors might close for good.

But, hell, in another year or two they might close anyway. A family business was a fragile thing, and Music City Salvage was on shaky legs.

But chestnut. But marble. But stained glass and built-ins and heart of pine. But the big locked box of the carriage house, and everything that might be waiting inside. The magical crapshoot of rust lust tugged at him harder than fear, harder than Barry would. Harder than caution, and harder than common sense, perhaps.

But what an opportunity. What a Hail Mary pass.

He stood up and reached for his coffee mug full of pens. While he rifled around for one that definitely worked, he declared, “Ms. Withrow, we’ve got a deal.”

“Excellent! Shall we summon your finance fellow, for approval?”

“Nah. He works for me—not the other way around.” At least until the first paycheck bounced.

She rose to her feet, papers in hand. “You are the boss, after all.”

“Damn right, I’m the boss.” He took her papers and signed where indicated. He produced a checkbook, started writing, then postdated the check by several days. “I’ll need to juggle some funds,” he explained. “I hope that’s all right.”

“Juggle away. I’ll sit on the check if you like, but you only have until the fifteenth to get the job done. That’s when the wrecking ball arrives, and your time is up.”

“Two weeks is good. We won’t need half of that.”

“I’m glad to hear it.” Then, for the first time, she hesitated. “And I’m glad that the things which can be saved … will be saved. I don’t know. Maybe you’re right, and maybe it’s a shame to see the place go. Maybe I should’ve tried to find a buyer … Maybe I should’ve…” She looked at the folder on his desk, and the check in his hand. For a split second, Chuck thought she might tell him to tear it up—but she rallied instead. “No, it’s done now. I’m done, and the estate ends here. Believe me, it’s for the best.”

Chuck handed over the check with two fingers.

Augusta Withrow traded it for a set of keys, and thanked him.

“No ma’am, thank you! And I promise we’ll do our best to treat the old place with the respect it deserves.”

Her face darkened, and tightened. “Then you might as well set it on fire.”

She left his office without looking back. The sharp echo of her footsteps rang from the concrete floor as she retreated the way she came—between the rows of steel shelving stocked with wood spindles, birdbath pedestals, and window frames without any glass. When she turned the corner beyond the row of splintered old doors, she was gone … and only a faint whiff of flowers, tobacco, and Aqua Net remained in her wake.

Chuck took a deep breath and held it, then let it go with a nervous shudder.

Forty grand was a lot of money, but he could swing it, he was pretty sure. He could rig up enough credit and cash to cover expenses for the next few weeks, until the Withrow stuff flew off the shelves and refilled those dusty corporate coffers.

“It’s a gold mine,” he reassured himself, since nobody else was there to do it. “This is a good idea. We can do this.”

“We can do what?”

He looked up with a start. He wasn’t alone, after all. His daughter leaned around the doorframe, peering into the office. “The Withrow estate,” he told her.

“What’s the Withrow estate?” Dahlia Dutton strolled inside and planted her ass in the same seat that Augusta had recently vacated. “Does it have something to do with that old lady who just left…?”

“Yup. That’s Augusta Withrow.”

She gazed across Chuck’s desk. “You cleaned up for her. She must be rich. Hey, wait—is this that place James was going on about? The one in Chattanooga?”

“That’s the one. You wouldn’t believe it—this lady’s just walking away from a gingerbread mansion with a carriage house and a barn. James said we could earn back a nickel on every penny.”

Dahlia’s eyes narrowed. “How many pennies, Dad? ‘Estate’ is usually code for ‘expensive.’”

“It was … a good number of pennies, yes. But it’ll be worth it.” He shoved Augusta’s folder across the desk.

Dahlia picked it up and opened it. She flipped through the first few pictures, scanning the highlights. She let out a soft whistle. “Many, many pennies, I assume. Please tell me this is an investment, and not a calamity.”

“Life is full of risks.”

“And this house is full of furniture,” she observed. “Why’s that?”

“It’s cheap shit, left over from yard sales and estate clearance.” He sat back in his chair. It leaned with a hard creak, but didn’t drop him. “We can take all that stuff, too—if we feel like it.”

“This isn’t all cheap shit.”

“Well, you’re the furniture expert, honey, not me.”

She nodded down at the images in her lap. “Some of these pieces are good. If the old lady doesn’t want them, sure, I’ll take them. I could use some furniture right now. I don’t care if it’s old and dusty. I’ll clean it up here, and take it back to my new place.”

Dahlia had just sold her house. It was part of the divorce agreement, since Tennessee is a communal property state—and neither she nor the ex could agree on who ought to keep it. Her new apartment was half empty, like it belonged to a bachelor or a college kid. In Chuck’s opinion, it was downright pitiful.

She sighed. “Jesus, Dad. Look at this staircase.”

“Chestnut.”

“Is it? Oh, wow, that’s great…” But that’s not what she was thinking, and he knew it. She was thinking about the staircase in the house she’d lost, and how it had gleamed in the muted, colored light from the stained glass in the front door sidelights.

“Honey, chestnut’s a whole lot better than great—and there’s a bunch more sitting out back, from the old barn. There’s a carriage house, too. Both of them have been locked up since before Ms. Withrow was born.”

Her face brightened. “Seriously?”

He’d figured that little tidbit might distract her. “That’s what she said.”

“And she must be ninety, if she’s a day. Let’s round it up to a hundred years, then. What did those buildings hold, a century ago?”

“I don’t know. I’m going to guess … carriages. And barn stuff.”

Dahlia tapped her finger on the folder’s edge. “We could pry open those doors and turn up anything, or nothing.”

“You’ll find out when you get there.”

“Hell yes, I will. What’s our time frame like?”

“Two weeks.” He cracked open the top desk drawer, and slipped his checkbook back inside it.

“We won’t need that long.”

He grinned. A child after his own heart. “I know, but I expect we’ll need more time than you think. We’re talking four acres, with several outbuildings. The house is some 4,500 square feet. And … I hate to mention it, but I can’t spare much in the way of manpower or resources right now. I’m counting on you, kid.”

“T&H? The dick joint?”

“Neither one of them’s paid up. But,” he said fast, “Barry’s got a lawyer up their asses, and they have until the end of this week, or we’re suing them.”

“Dad…” She sighed.

“I know, I know. It’ll be tight for a month or so, that’s all. But once you get the Withrow house gutted, I’ll fire off a flashy press release, then we can sit back and watch the money roll in. These places don’t hit the market every day of the week—you just watch, we’ll have designers and construction guys coming out from both coasts, and Canada, too.”

“I hope you’re right. Because if you’re wrong…”

“I’m definitely right. We just have to hang on until we get the stock back here, sorted out, and tagged for sale,” he promised.

She might’ve believed him, or she might’ve just been resigned to her fate. He couldn’t tell which when she said, “Then I’d better work fast. Who’s coming with me?”

Now for the fun part. He didn’t want her to bite his head off, so he started out easy. “You’d better take Brad, for starters.”

“Has Brad ever actually done a salvage run?”

“Ask him. He might have. You’ll want to keep one eye on him when he’s using the power tools; but he knows his shit on paper, and he might be useful if you run into permission problems. The place is right outside Saint Elmo, on Lookout Mountain … and the historic zoning folks might get ideas about what belongs where. Supposedly this ain’t any business of theirs, but that doesn’t mean you won’t hear from them anyway, when they see you pulling the house apart.”

“Fair enough.” She slapped the folder back down on his desk. “Who else?”

Next he proposed his great-nephew. “Gabe’s done a couple of jobs, now.”

“Gabe’s just a kid.”

“He’s a big-ass kid—that boy can swing a sledge like Babe Ruth. Best of all, he adores you, and he’ll do whatever you tell him.”

“All right, Gabe’s in. Who else will I wind up babysitting on this gig?”

Chuck hemmed. He hawed. “Well, James is out picking in Kentucky this week, and Frankie’s got to work the floors. I have to hang around and play manager—and that’s my least favorite thing, so you know I don’t have a choice. Melanie’s got the register and phones … and that’s everyone we have on deck, except Bobby.”

Dahlia stopped smiling.

Chuck squeaked, “Baby?”

“Of all the idiots…”

“He’s not an idiot. You’re just mad at him.”

“I judge him by the company he keeps. Besides that, he’s lazy as hell, and you know he won’t take orders from me.”

“If he won’t, he can pack it in. This is a business, not a charity.”

“Bullshit. You never could tell your sister no.”

Chuck threw up his hands. “All right, fine—it’s bullshit, but he’s in a bind, and I don’t care how well he gets on with Andy. I’ll have a talk with him before you go. He’ll behave himself, Dolly.”

“Don’t call me that.”

“Dahlia. He’ll work his ass off, and he’ll answer to you—or he’ll answer to me. He needs the gig, now that Gracie’s gone, and he’s got Gabe to think about.”

“You say that like she’s dead.”

“She’s dead to him.”

She yawned, and didn’t try to hide it. “Jail is temporary.”

Chuck stared helplessly at his only child. More gently, this time, he tried another approach. “Look, I know Bobby’s not your favorite cousin right now, but it’s only for a few days. Let’s say four days, all in—including me and the Bobcat on the Doolittle. I’ll come up for the last day, and help load up the big stuff.”

“That sounds about right.”

“Five days, and it’s a big house. You two will hardly have to see each other, and Gabe will be glad to have you around. You’re the responsible adult he’s always wanted.”

“He’s a good kid,” she grudgingly granted. “I can work with him. And Brad’s not so terrible.”

“Brad’s not terrible at all, he’s just not a handyman—but we can fix that. He’s a quick learner. He just needs the guidance of an experienced professional like yourself.”

“Flattery will get you nowhere, and Brad’s a quick reader. That’s not the same thing as a quick learner. Now I’m supposed to provide on-the-job training, too? Maybe I need a raise.”

“Think of it as an upgrade to a supervising position.”

“One of those promotions that doesn’t come with any money? Yeah, thanks.” Then she warned, “If Brad cuts off a thumb…”

“Then our insurance premiums go up, and Brad types his thesis a little slower. Now it’s settled,” Chuck declared. That didn’t make it so—but a man could pretend. “You’ll head out tomorrow, and take the two twenty-six-footers; that’ll get you started. I’ll drive down on Friday with the forklift, and then we can take down the exteriors.”

“You think the trucks will hold it all?”

“I hope not. I hope and pray we fill ’em both up to the brim, and when I show up with the one-ton trailer, I hope it barely holds the rest—and then we have to rent another one. Or steal one. This score’s on a shoestring, honey.”

He shouldn’t have emphasized that part. He knew it by the pair of vertical lines that appeared between her eyebrows.

“Daddy, how much money did you pay out for this? Tell me the truth.”

“Forty.” It came out hoarse. He cleared his throat, and said it stronger. “Forty grand, that’s all. Drop in the bucket, on a project like this. A nickel for every penny, just like James said.”

“Forty…,” she echoed the figure. “Do we even have that much money right now?”

“Well…”

“Christ, Daddy. This’ll be the death of us, won’t it?”

“Think positive, baby.”

“All right, I’m positive this’ll be the death of us.”

“No, no it won’t. You have faith in me, and I’ll have faith in you. I’ll make the money work, and you’ll bring home the golden goose.”

She sighed hard. “So you’ll do the math, if I’ll do the heavy lifting. Got it.”

“Atta girl.” An idea sprang into his head, and he let it fly before he could talk himself out of it—and before Dahlia could second-guess him. “Speaking of heavy lifting, I’ve got an idea. Since we’re hanging by a thread until the Withrow loot starts selling … why don’t the four of you go camping.”

“Beg pardon?”

“You saw the pictures of the big house; it’s furnished, sort of. The contract says the power stays on through the fourteenth, so we can run the equipment, no problem. There’s no central heat or air, but that’s all right. It’s cool enough now that you won’t need the AC. If it gets too cold at night, there are seven fireplaces in that old behemoth. One of ’em must work.”

“Dad…”

“Otherwise, we’re talking four or five nights in a hotel. Three rooms, and that’s because I’m willing to bunk with you when I arrive. It adds up, darlin’. It’s an unnecessary expense, when you’ve all got sleeping bags and we’re running short.” He talked faster as he warmed to the thought. “You can wake up in the morning, make yourself some coffee, and get started. Head on down to Saint Elmo for meals, and charge it all to Barry’s AmEx. Minimal interruption, minimal downtime. Just start in the rooms you aren’t sleeping in—work from top to bottom, maybe. Better yet, start with the outbuildings, and work your way in.”

“Dad,” she said more firmly, cutting off his sales pitch. “It’s okay. I’ve done it before, remember?”

“That’s right—you stayed at the Bristol joint last year. But that was only an overnight.”

“So? Everything was fine. It’s no big deal. We can start early, work late, and get the job done fast. We’ll turn off the power and bust out the generators when you arrive, then take the windows and fixtures last. It’s totally doable.”

She gave the photos in her lap another pass, shuffling them around until her eyes caught on this detail, or that fixture. “What a beautiful place,” she said softly. “The bones look great, but maybe that’s just the pictures. Did that woman even try to sell it?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it needs too much work. Maybe it’s just not worth it, to her, or anybody else.”

She shook her head. “I don’t believe that.”

“Wait until you see it in person,” he urged. “You might change your mind. For all we know, the foundation is shot, and the walls are full of termites and rats.”

“You want to change my mind about sleeping in this place? Keep talking.”

“Oh Dolly-girl, my Snow White child,” he teased her, like when she was small. There was a children’s book he used to read her about a little girl who got lost in the woods. Even these days, they knew it both by heart. “The rats will give you gifts, and the bugs will give you kisses. The bats will stand guard as you sleep, and the owls will keep watch from their tree.”

She tried to muster a smile, and almost succeeded. “So it’s always been, and may it always be.”

Copyright © 2016 by Cherie Priest

Buy The Family Plot here:

Masters of Death by Olivie Blake

Masters of Death by Olivie Blake by T.L. Huchu

by T.L. Huchu Just Like Home by Sarah Gailey

Just Like Home by Sarah Gailey The Family Plot by Cherie Priest

The Family Plot by Cherie Priest Library of the Dead by TL Huchu

Library of the Dead by TL Huchu by Stephen Graham Jones

by Stephen Graham Jones The Bone Orchard by Sara A. Mueller

The Bone Orchard by Sara A. Mueller by TJ Klune

by TJ Klune

Kristin Temple, Associate Editor

Kristin Temple, Associate Editor Jordan Hanley, Marketing Manager

Jordan Hanley, Marketing Manager Julia Bergen, Marketing Manager

Julia Bergen, Marketing Manager Theresa Delucci, Senior Marketing Director

Theresa Delucci, Senior Marketing Director Rachel Taylor, Marketing Manager

Rachel Taylor, Marketing Manager Lizzy Hosty, Marketing Intern

Lizzy Hosty, Marketing Intern Angie Rao, Design

Angie Rao, Design Title:

Title:

The Doll Collection

The Doll Collection

Alone with the Horrors

Alone with the Horrors

Hell House

Hell House HEX

HEX The Mothman Prophecies

The Mothman Prophecies The Keep

The Keep Dark Harvest

Dark Harvest Legion

Legion I Am Not A Serial Killer

I Am Not A Serial Killer

The Family Plot

The Family Plot The First Days

The First Days Nightflyers & Other Stories

Nightflyers & Other Stories Stranded

Stranded The House of Cthulhu

The House of Cthulhu The Five

The Five

Malus Domestica series

Malus Domestica series Stygian

Stygian Graveyard Shift

Graveyard Shift