Is a real utopia possible and do we want to achieve one? We interviewed three political science fiction authors about the future societies they create in their novels.

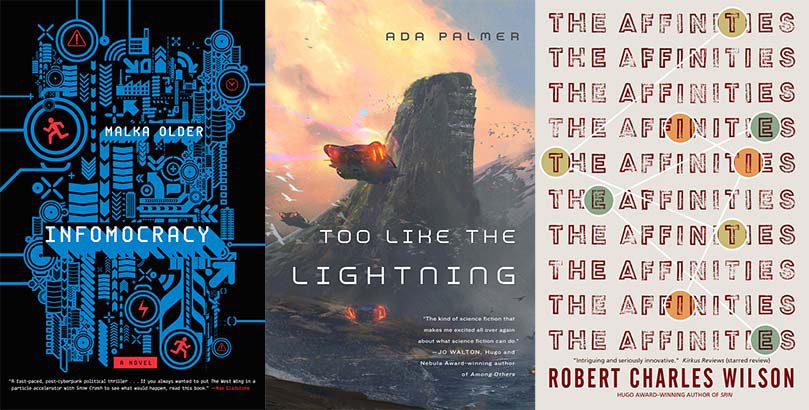

Infomocracy, the debut novel from humanitarian worker Malka Older, is a post-cyberpunk thriller that envisions a future where elections play out on a worldwide scale. It’s been twenty years and two election cycles since Information, a powerful search engine monopoly, pioneered the switch from warring nation-states to global micro-democracy. The corporate coalition party Heritage has won the Supermajority in the last two elections. With another election on the horizon, the Supermajority is in tight contention, sabotage is threatened, and everything’s on the line, testing the limits of the biggest political experiment of all time.

Too Like the Lightning, historian Ada Palmer’s first novel, is set in a peaceful, affluent future where superfast transportation makes it commonplace to live on one continent while working on another and lunching on a third. Antiquated “geographic nations” have been replaced by borderless governments whose membership is not determined by birth, but by individuals choosing the nations which reflect their identities and ideals, while rulers and administrators of inestimable subtlety labor to preserve the delicate balance of a world where five people affected by a crime might live under five different sets of laws.

From Robert Charles Wilson, the author of the Hugo-winning Spin, The Affinities is a compelling science fiction novel about the next ways that social media will be changing everything. In the near future people can be sorted by new analytic technologies—such as genetic, brain-mapping, and behavioral—and placed in one of twenty-two Affinities. Like a family determined by compatibility statistics, an Affinity is a group of people most likely to like and trust one another, the people one can best cooperate with in all areas of life: creative, interpersonal, even financial. It’s utopian—at first. But as the differing Affinities put their new powers to the test, they begin to rapidly chip away at the power of governments, of global corporations, of all the institutions of the old world. Then, with dreadful inevitability, the different Affinities begin to go to war with one another. His most recent novel is Last Year.

How do you draw the lines of political division in your novel?

Malka Older: Because Infomocracy is set during an election, the actors spend a lot of time drawing the lines of division themselves—with political advertising, in debates, in their informal discussions. But the setting of micro-democracy, which in the book has existed for decades, also allowed me to show some of the ways that these different political approaches might play out in practice. As characters move from one centenal—a geographic unit with a population of 100,000 people—to another, which in a dense city could be every couple of blocks, they see changes in laws, cultures, and commerce. It’s a fun place to hang out, at least for political geeks and writers.

Ada Palmer: Because my governments are based on choice instead of birth, the divisions are based on identity, and on what kinds of underlying principles people want their governments to have. For example, there is one group that focuses on warm and humanitarian activities, education, volunteerism, and attracts the sort of people who want to be part of something kind and giving. There is another group that has stern laws and an absolute monarchy, which attracts people who like firm authority and strong leaders, but it can’t get too tyrannical since, if the monarch makes the citizens unhappy then no one will choose to join that group; so the leader has to rule well to attract subjects. There’s another group that focuses on progress and future-building, imagining better worlds and sacrificing the present by toiling to build a better future. So the differences aren’t liberal vs. conservative really, or one policy vs. another, but what people feel government is for in the first place, whether it’s about strength, or about helping people, or about achievement, or about nationhood, or about being a good custodian of the Earth, the big principles which underlie our thinking before we start judging between candidate 1 and candidate 2.

Robert Charles Wilson: In a sense, the lines are drawn by my novel’s premise. Over the course of the story we get a look at the personal and internal politics of the Affinity groups, the politics of inter-Affinity alliance-making, and the relationship of the Affinities to the conventional political and cultural institutions they attempt to co-opt or displace.

Why did you choose your main character as the narrator and how do they engage the audience?

Robert Charles Wilson: Adam Fisk is a young man facing a broad set of the familiar problems the Affinity groups claim to address—a less-than-perfectly-functional birth family, money woes, a stalled career path, a social isolation he can’t quite climb out of. He embodies a certain longing we all feel from time to time: the sense that a better, more fulfilling, more meaningful way of life must be possible. Like many of us, he’s looking for a door into a better world. Unlike most of us, he becomes convinced he’s found it.

Ada Palmer: Mycroft Canner is a very peculiar narrator, based closely on 18th century memoirs and philosophical novels, especially Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist. This kind of narrator has very visible opinions, often interjecting long tangents about history or philosophy and using direct address, “Gentle reader, don’t judge this frail man too hastily, for you see…” I wanted to write in this Enlightenment style because authors of that era, like Voltaire and Montesquieu, loved to ask big questions about things like government, law and religion, questioning whether elements people thought of as “natural” and “universal” like aristocracy, or retributive justice, or gender segregation, might not be so natural and universal.

Modern science fiction is very much in that tradition, of course, imagining other ways society might be set up and using them to make us question our assumptions about our own world, but I love how Enlightenment narrators voice the questions overtly instead of having them be implicit, because the narration is like a time capsule. When we read an Enlightenment novel like Candide or Jacques the Fatalist today, we don’t have the same questions about the events that the authors ask in their narration, because we come from a different time and have different big questions on our minds. We’re at a different stage in the history of social class, gender equality, monarchy vs. democracy, religion, so the questions Voltaire or Diderot ask about these issues, preserved in the time capsule of their narration—are often more surprising and delightful to us than the stories themselves.

Malka Older: Infomocracy shifts among the points of view of multiple main and secondary characters. This reflects the multi-polar nature of the world and the multiple layers of information and misinformation, but it also serves to engage the readers across multiple competing but valid perspectives. Most of the main characters are working hard for an outcome they honestly believe in; allowing them each a voice gives the reader a chance to identify with each and, hopefully, engage more deeply on these difficult questions.

Would you describe the society in your book as a utopia? Why or why not?

Robert Charles Wilson: The Affinities is a book about the utopian impulse, of which (I feel) we should be skeptical but not dismissive. Part of the book’s premise is that the advance of cognitive science has made possible a practical utopianism, a utopianism that derives from a genuine understanding of human nature and human evolutionary history rather than from the imagined dictates of divine will or pure reason. And the Affinity groups aren’t the last word in that struggle. The book holds open the possibility of even newer, more radical communal inventions.

Ada Palmer: I think Bob’s characterization applies well to all three of these books, that none is a strict “utopia” in that none of them is trying to portray a perfect or ideal future, but they are all about utopia and utopianism, about human efforts to conceive and create a new, better society. In that sense they’re all addressing hope, not the hope that a particular set of institutions would solve all humanity’s problems, but the hope that humanity will move forward from its current institutions to try new ones that will work a bit better, just as it moved to the current one from earlier ones. There is a lot of anti-utopian science fiction, in which we are shown a world which seems utopian but turns out secretly to be achieved through oppression or brainwashing etc. It’s refreshing to me to see a cluster of books which aren’t that, which are instead about new ways the world could be run which would be a step forward in some ways, if not in others. My book’s future especially I think of as two steps forward, one step back: poverty has been dealt with but censorship has come back; religious violence has ended but at the cost of lots of religious regulation; current tensions about race and gender have evolved into new different tensions about race and gender. Looking at real history, that is how historical change tends to work, improvements on some fronts but with growing pains and trade-offs; for example, how industrialization let people own more goods and travel more freely, but lengthened the work week and lowered life expectancy, gain and loss together. I think all three of our books suggest—against currents of pessimism—that that kind of change is still valuable, and that “better” is a meaningful goal even if “perfect” is off the table. Certainly it’s meaningful to discuss; this kind of thought experiment, exploring alternate ways of living, is so much of what science fiction is for.

Malka Older: It sounds like we’re all on the same page in terms of utopias. As Ada says, I think it’s a very positive step not only to be writing with hope, but also writing stories that move away from the absolutes of utopias and dystopias (as a side note: it’s interesting how trendy the dystopia label has become recently; among other things, it means the bar for calling something a dystopia is far lower than that for labeling a utopia < \pet peeve>). Imagining a perfect society can be paralyzing: as a narrative function it requires a kind of stasis that’s not very exciting, and as a policy prescription it becomes the enemy of incremental, imperfect solutions. At the same time, without expecting perfect, we need to keep demanding better, and better, and better.

Robert Charles Wilson: Seems to me that utopia—if we define utopia as a set of best practices for enabling justice, fairness, freedom, and prosperity across the human community in its broadest sense—is more likely a landscape of possibilities than a single fixed system. Maybe utopia is like dessert: almost everybody wants one, but not everyone wants the same one, and only a generous selection is likely to satisfy the largest number of people.

What do you want readers to take away from your novel?

Robert Charles Wilson: I wanted both to validate the discontent Adam feels—yes, we should want better, more generous, more collaborative communities than those we currently inhabit—and to offer a warning against what one of the characters calls “walled gardens,” communities that thrive by exclusion.

Malka Older: It’s easy to assume that the particular configurations of our specific place and time are part of the landscape: decided, almost invisible in their unquestioned existence, all but immutable. I hope Infomocracy brings readers to question their assumptions about democracy, nation-states, and government in general, to think creatively about all the other possible systems out there and the ways in which we might tinker with ours to make it more representative, equitable, informed, and participatory. For me, Infomocracy is a hopeful story, because even if the new systems don’t always work out as planned, the people who care about them keep trying to make them better.

Ada Palmer: Lots of new, chewy ideas! I love when readers come away debating, not just “Which political group would you join if you lived in this world,” which is fun, but debating the different ways of thinking about what social institutions like government or organized religion are, or are for, in the first place. Real world politics often gives us space to debate the merits of different policies, but it doesn’t often invite us to go past “Should farming be regulated X way or Y way” or “Should there be separation of Church and State?” to the more fundamental question of what the purpose is of regulation, government, Church, or State in the first place. What I love is when readers first debate which government they would chose, and move from that to debating how having a choice of governments in the first place would change the way we participate, and the way we do or don’t think of national identity as part of ourselves.

Malka Older is a writer, humanitarian worker, and Ph.D. candidate at Sciences Po, studying governance and disasters. Buy her novel Infomocracy at Amazon │ Barnes & Noble │ iBooks │ Indiebound

Ada Palmer is a professor in the history department of the University of Chicago, specializing in Renaissance history and the history of ideas. She is also a composer of folk and Renaissance-tinged a capella music, most of which she performs with the group Sassafrass. Buy her novel Too Like the Lightning at Amazon │ Barnes & Noble │ iBooks │ Indiebound

Robert Charles Wilson was born in California and grew up in Canada. He has won the John W. Campbell and Philip K. Dick awards, as well as the Hugo Award for Spin. His most recent novel is Last Year. Buy his novel The Affinities at Amazon │ Barnes & Noble │ iBooks │ Indiebound

Can’t wait for The Name of All Things? Same. But don’t worry, it’s just a few more months.

Can’t wait for The Name of All Things? Same. But don’t worry, it’s just a few more months.

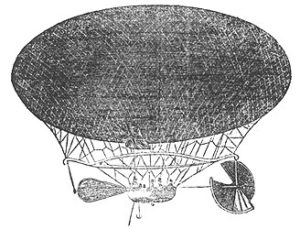

My drag rope idea, though similar on the surface, would prove to be anything but plausible. It turned out that a drag rope had already been tried in S. A. Andrée’s Arctic Balloon Expedition of 1897. Far from out-sailing seagoing vessels, Andrée reported that his balloon could only steer ten degrees from the direction of the wind, and modern experts believe that even this meager claim was an absurd exaggeration. Worse, the failure of their sailing scheme was a contributing factor to the deaths of all three expedition members.

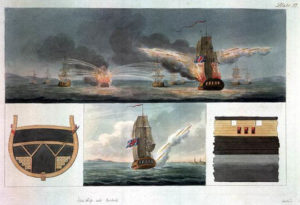

My drag rope idea, though similar on the surface, would prove to be anything but plausible. It turned out that a drag rope had already been tried in S. A. Andrée’s Arctic Balloon Expedition of 1897. Far from out-sailing seagoing vessels, Andrée reported that his balloon could only steer ten degrees from the direction of the wind, and modern experts believe that even this meager claim was an absurd exaggeration. Worse, the failure of their sailing scheme was a contributing factor to the deaths of all three expedition members. Broadsides of rocketry don’t have the satisfying thunder of cannons, and I could think of no plausible way of following my broadsides with a boarding action—and without a boarding action, a broadside just feels empty, doesn’t it?

Broadsides of rocketry don’t have the satisfying thunder of cannons, and I could think of no plausible way of following my broadsides with a boarding action—and without a boarding action, a broadside just feels empty, doesn’t it? And you know what weighs about a ton and a half? Two twelve-pounder carronades, plus ammunition and minimum gun crews. I decided not to waste time or risk disappointment by rechecking my math, but proceeded straight to sketching out the placement and capabilities of what would become Mistral’s light cannons, or “bref guns.” Now, bref guns are still implausible for other reasons—we won’t even contemplate the real-world effect of their recoil on Mistral’s airframe—but let’s be frank here; if you can find the merest excuse to put cannons on your steampunk airship, you put cannons on your steampunk airship, or you’re a damn fool.

And you know what weighs about a ton and a half? Two twelve-pounder carronades, plus ammunition and minimum gun crews. I decided not to waste time or risk disappointment by rechecking my math, but proceeded straight to sketching out the placement and capabilities of what would become Mistral’s light cannons, or “bref guns.” Now, bref guns are still implausible for other reasons—we won’t even contemplate the real-world effect of their recoil on Mistral’s airframe—but let’s be frank here; if you can find the merest excuse to put cannons on your steampunk airship, you put cannons on your steampunk airship, or you’re a damn fool.

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. Of course, the jungles of the subcontinent aren’t fictional. It’s just that this was the first book where I saw a wilderness treated remotely in fiction like an ally and protector, with its own languages and laws, instead of a hostile thing to be conquered. Wiser people than I have much valid criticism to heap on this book, and yet I still sometimes dream of stretching out on a rainforest limb beside Bagheera and Baloo.

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. Of course, the jungles of the subcontinent aren’t fictional. It’s just that this was the first book where I saw a wilderness treated remotely in fiction like an ally and protector, with its own languages and laws, instead of a hostile thing to be conquered. Wiser people than I have much valid criticism to heap on this book, and yet I still sometimes dream of stretching out on a rainforest limb beside Bagheera and Baloo. . The Hobbit seems to be about dwarves, elves and metaphors for sensible, down-to-earth English folk, but really, it’s all about the trees. More, it’s about how trees are good and the industrial revolution is bad.Tolkien lovingly names and describes them—oak, ash, beech, birch, rowan, willow. Tom Bombadil, a forest god, and Goldberry, a river goddess, seem the only incorruptible aspects of Middle Earth. Baddies cut trees down. Goodies, in contrast, reside in or amongst trees. Or hide in them from wargs. Galadriel’s magic sustains the Mallorn trees of Lothlorien which, instead of losing their leaves, turn golden and glitter. These trees, along with others of Mirkwood, the Old Forest and Fangorn can accumulate wisdom, act in the interests of good or evil, and are as beautiful, vital and alive as the speaking characters.

. The Hobbit seems to be about dwarves, elves and metaphors for sensible, down-to-earth English folk, but really, it’s all about the trees. More, it’s about how trees are good and the industrial revolution is bad.Tolkien lovingly names and describes them—oak, ash, beech, birch, rowan, willow. Tom Bombadil, a forest god, and Goldberry, a river goddess, seem the only incorruptible aspects of Middle Earth. Baddies cut trees down. Goodies, in contrast, reside in or amongst trees. Or hide in them from wargs. Galadriel’s magic sustains the Mallorn trees of Lothlorien which, instead of losing their leaves, turn golden and glitter. These trees, along with others of Mirkwood, the Old Forest and Fangorn can accumulate wisdom, act in the interests of good or evil, and are as beautiful, vital and alive as the speaking characters. The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. LeGuin. The title says it all, really (it’s a great title, isn’t it?) With it, LeGuin reminds us that our home planet is “Earth.” In many science fiction stories, including this one, we appear as “Terrans.” We’re all about the dirt, not the ecosystems supported by it, not just because agriculture is the basis of Western civilisation but because our religions or philosophies of superiority rely on separating ourselves from “lower” forms of life.

The Word for World is Forest by Ursula K. LeGuin. The title says it all, really (it’s a great title, isn’t it?) With it, LeGuin reminds us that our home planet is “Earth.” In many science fiction stories, including this one, we appear as “Terrans.” We’re all about the dirt, not the ecosystems supported by it, not just because agriculture is the basis of Western civilisation but because our religions or philosophies of superiority rely on separating ourselves from “lower” forms of life. The Broken Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin. Like Warren’s work, the second book of Jemisin’s Inheritance trilogy is set beneath the canopy of a single, enormous tree. I loved the transformative power of this tree, the monolithic inability to ignore it. The rustle of its leaves was part of the music of this rather musical book—the main character couldn’t see—and the roots and branches grew and disturbed the order of the city of Shadow. But also, as with the Warren, the tree was a power that divided people, as opposed to bringing them together.

The Broken Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin. Like Warren’s work, the second book of Jemisin’s Inheritance trilogy is set beneath the canopy of a single, enormous tree. I loved the transformative power of this tree, the monolithic inability to ignore it. The rustle of its leaves was part of the music of this rather musical book—the main character couldn’t see—and the roots and branches grew and disturbed the order of the city of Shadow. But also, as with the Warren, the tree was a power that divided people, as opposed to bringing them together.