Written by Lauren Jackson

First, a confession: my series rewatches are always ill-timed and off by a few months, perhaps a result of working in the book publishing industry and learning to live and think a year ahead of schedule (at minimum).

As such, I conducted a thorough rewatch of Battlestar Galactica early in 2017 because of a confluence of circumstances that humans would describe as serendipitous and Cylons would describe as God at work in my life: I a) found out that 2017 was the 25th anniversary of SyFy as well as the 40th anniversary of the airing of the original Battlestar Galactica series (the popular reboot is a pubescent nugget at 13); b) also found out Tor Books was publishing SO SAY WE ALL, an oral history of the two series, in celebration; c) started dating someone who was a huge SFF fan with an impressive book library and a less than impressive film/tv one, who had never watched the new series; and d) got sober and started following a spiritual practice for the first time.

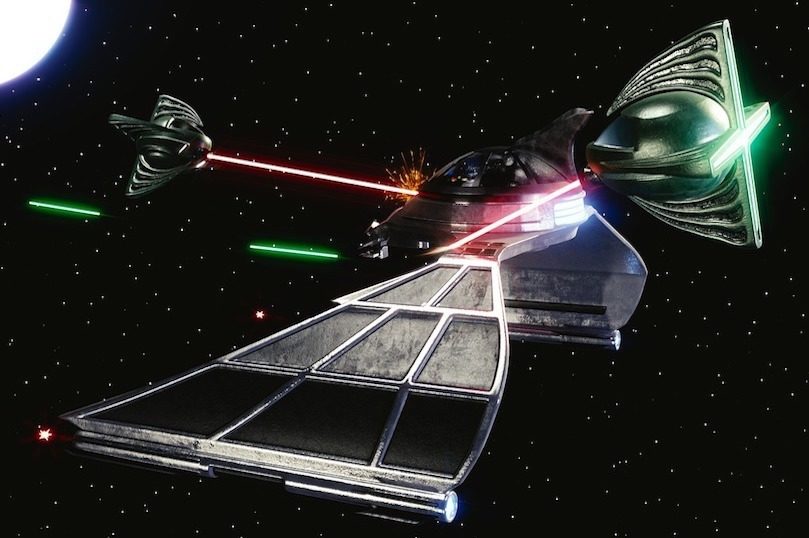

Turns out I was about six months early. Back then, I had an overwhelming amount of thoughts on the series as its impact on me after that second rewatch was far stronger than the first. I caught new things, subtle things, that I’d missed initially as I was distracted by stunning battle scenes, towering characters, and one of the best examples of worldbuilding in sci-fi television. (NB: Before you all lose your cool, I said “one of the best” not “the best.” Slow your roll.)

Anyway, those thoughts have since quieted and, looking back on the nuances that came into focus, I realized something interesting: the reason they hit me so hard was because they were perfectly/insanely/oddly applicable to my life and the new path I followed and, had I listened to BSG’s subtle messages sooner, I would’ve started down that path much earlier (but I didn’t, and that’s okay; hindsight is 20/20, right?).

So, without further ado, here are my 9 life lessons from watching Battlestar Galactica.

What isn’t growing is dying, or don’t get too comfortable

At the start of BSG, we’re introduced to a humanity resting very comfortably on its laurels…their worlds are at peace, and a long-forgotten enemy is far away and silent. They’re so comfortable, in fact, that the one dude who’s supposed to liaise with the Cylons if they show up literally falls asleep on the job. Humans are following rote procedure into oblivion. They’ve stagnated totally and are living in Cold War-esque grey area where they aren’t really at peace but they aren’t really at war either… and they aren’t making any moves to resolve it. So the Cylons resolve it for them. On the brink of eradication, the ones who step up, ready to take on new and challenging roles—Adama, the crew of Galactica, Laura Roslin—are the ones who survive.

Destined to live up to the Pythian adage “All this has happened before…” history does, in fact, repeat itself when humanity settles on New Caprica. Much as I hate the “Fat” Lee thing, the intent behind it is clear, and Adama says it outright: everyone’s gone soft. Humanity has grown complacent and, as such, are at risk of dying again. The only thing that can save humanity (again) is radical and unprecedented action: a rescue attempt in which Galactica enters New Caprica’s atmosphere in what might be the best action scene in the entire series…hell, the entire franchise.

It’s okay to believe in a higher power

As with most things these days, religion—and spirituality, by proxy—has become a divisive and partisan issue. Either you’re in it, or you think it’s pretty hokey. As someone who has recently adopted a spiritual practice and discovered its power to improve my life, I struggle against external and, even harder, internal biases, but BSG gave me courage through its portrayal of religion to embrace what I feel and practice it without contempt of self.

To openly talk about believing in a god or gods, pray, or express your piety in any way is considered lowbrow and unintelligent. To employ any of that in science fiction (without reconfiguring the belief system into something so foreign to readers/viewers that we can ignore context) is nearly unheard of. Yet, in BSG, the doubting Thomases like Baltar (at the beginning) are the least sympathetic characters. Whether worshipping Athena and Artemis or the singular Cylon god, faith delivers our beloved characters from evil without fail. The power of spirituality is on full, unapologetic display in BSG, and it’s heartening to see that those who practice it (i.e. nearly all characters) are intelligent, critical thinkers without maniacal zealousness. It’s another example of the show’s trailblazing nature.

Just because someone is in charge doesn’t mean they know better than you

Rarely do we see characters on BSG blindly following orders that go against their gut instincts… and when they do, it often ends in disaster. The best characters in the show question and challenge authority, sometimes to the point of mutiny (see: the assassination plot against Admiral Cain, the coup on the Astral Queen, the Resistance movement on Cylon-occupied New Caprica, Kara Thrace’s retrieval of the Arrow of Apollo, Caprica Six’s murder of Number 3 to save Anders, Natalie Faust (a Number 6 model) staging a rebellion against the lobotomization of the Cylon raiders).

Step up even when you’re not sure you can

From the miniseries through to the end of the show, humans commit remarkable acts against impossible odds and all expectations. Adama is the captain of a relic of a ship with a crew that has never seen combat, yet they mobilize after the Cylon attack and almost single-handedly save what’s left of the human race. Lee Adama, who has never practiced law before, chooses to defend the hated Gaius Baltar at trial, alongside everyone’s favorite crazy cat lady, Romo Lampkin. These characters saw an unmet need and, because of a sense of duty or justice or whatever, they did a thing they weren’t ready for…and they were useful.

Make sacrifices for the greater good. The right choice isn’t usually the one that feels good

Whether you agree with them, or even like them, those who survived on BSG were the ones who made the most difficult (and sometimes self-sacrificing) choices. Tigh orders the venting of a compartment with crew in it, knowing they’d die; Adama and Roslin choose to jump from Cylon attack, knowing they’ll leave the ships without FTL drive, and the people on them, behind; Helo gives up his seat for Gaius Baltar; and, perhaps the most controversial decision of all (at least in the audience’s eyes), Roslin bans abortion and makes it illegal.

Now I’m going to take the unpopular stance and say that Roslin did the right thing. She goes so far as to say that the decision defies all of her own beliefs, but it has to be done for human survival. The decision is desperate and painful for her, but she does it anyway, and I like to think that the writers included it because of the fan outcry it would cause alongside the characters, breaking the fourth wall in an incredible way.

In order to survive, you have to live one day at a time

Before she died, my grandmother gave me indispensable advice that I didn’t understand at the time: “Take life as it comes.” It sounded nice, but what was lost on me was the other side of the coin: if you don’t live presently, one day at a time, your preoccupation with the future or the past will kill you. Maybe literally, not in real life, but certainly on BSG. The starkest example of this in the show was also its most hopeless: after discovering Earth in ruins, Dualla shoots herself, choosing death rather than the uncertain future. On the flip side, the characters who live “presently,” who adapt to the new and seemingly unending challenges of every day, like Gaius Baltar and Bill Adama, are the ones who survive.

There are some things you can’t change

A really smart person once told me “There are apples in the world, and there are oranges. You’re an orange, and you’ll never be an apple, so stop trying.” One of the show’s catchphrases also comes to mind here: “All this has happened before, and all of it will happen again.”

Denying our true nature is an exercise in futility, but we see the Cylons go at it again and again. As Starbuck pointed out in Ep 1___ before she interrogates the captured Leoben, “But they [the Cylons] sweat. Now that’s interesting.” And it really is. The Cylons have gone through the trouble to look so human that it takes a sophisticated detector to find the “real” humans from the Cylon fakes. Yet, despite these exhaustive efforts, the Cylons never quite “pass.” They’re different at their core: physically stronger, more able to endure harsh conditions, perhaps even a bit more sterile, more analytical, and more calculating than their human creators. It’s really only when they accept their differences and use them as a complement to humanity’s that they succeed in their efforts to merge societies.

But you should have the courage to change the things you can

One of my favorite episodes in the series is 218: Downloaded. It’s the first deep examination of the Cylons and their society, a true anthropological study of the Cylon’s culture, motivations, and social structure. Plus, Xena Warrior Princess Number Three. Anyway… what I like best about it is how Caprica Six and Sharon defy the audience’s assumptions that the Cylons are cold, uniform creatures ruled by programming. They’re celebrities among the Cylons, representing individuality among uniformity. They’re dangerous, and they don’t disappoint when they rebel against their Cylon siblings to formulate a new plan for the shared future of Cylons and humans.

A friendly reminder: women don’t need men to rescue them

No one on BSG is more daring, unconventional, or reckless than Kara Thrace, and that’s undoubtedly why she finds herself in the stickiest situations throughout the series. But never—not once—does she need rescuing from her male counterparts. The show defies the trope of “powerful female heroine needs rescuing” as the climax of an episode time and time again. Marooned on a planet, Starbuck gets herself the hell out of there by using her skills as a viper pilot to learn and operate with some panache the heretofore unknown controls of a Cylon raider. Again, later on, she extricates herself in the nick of time from her Leoben captor as the Galactica comes to rescue humanity from its failed attempt at colonization under Cylon governance. And here’s the thing: it all. Makes. Sense. Kara is characterized as the most talented viper pilot, and perhaps the most ruthless officer under Adama’s command (which is why Admiral Cain takes such a liking to her and why Adama the Elder tasks her later with the Admiral’s assassination); it would be a major failing on the writers’ part to put Kara in a situation from which she couldn’t escape, whether by ship or by her own hand. Of course, that doesn’t stop other TV shows and movies from indulging the rote trope, so it’s a true triumph of continuity, fidelity, and feminism that the writers of a trailblazing show kept Starbuck empowered and autonomous…as she should be.

Order Your Copy of So Say We All

Chaotic pairings drive some of the best SFF. Plot arcs in fantasy especially are often too predictable: the dark lord always goes down in the end, the hero triumphs at great personal cost, some innocent fools get saved, so on. It’s difficult to get away from this equilibrium, so the originality has to come from the characters. I’m just going to run through a few of my favorites in no particular order.

Chaotic pairings drive some of the best SFF. Plot arcs in fantasy especially are often too predictable: the dark lord always goes down in the end, the hero triumphs at great personal cost, some innocent fools get saved, so on. It’s difficult to get away from this equilibrium, so the originality has to come from the characters. I’m just going to run through a few of my favorites in no particular order.