Written by A. J. Hartley

Written by A. J. Hartley

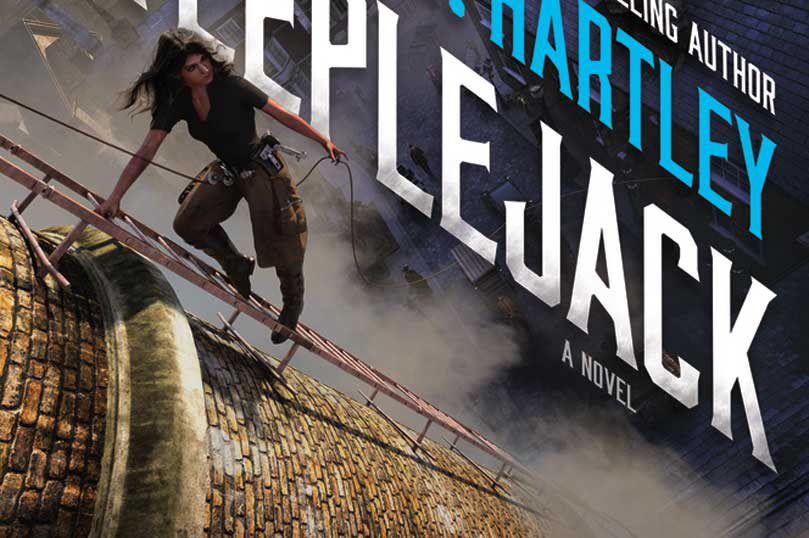

My most recent novel, Steeplejack, is a vaguely steampunky fantasy adventure that centers on Anglet Sutonga, a woman of color. She lives in the city of Bar-Selehm, a place which does not actually exist and never has. The city looks a bit like South Africa but looks more like Victorian London than South Africa ever did, and its political system looks more like apartheid than like the early years of colonialism.

What this means, of course, is that I’m inventing the world and its people, drawing on current issues as much as I am those of the past, and mixing those with known histories. I am not a person of color (POC), and my writing one may raise issues that can be encapsulated by what I call “the Jurassic Park conundrum”: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn’t stop to think if they should,” or more simply as, “Why?”

There are several really good reasons why white guys shouldn’t write POC characters. First, they often do it badly, and by badly I don’t just mean incompetently, clumsily, or unconvincingly, but offensively. Too often writers play upon stereotypes and white notions of what it means to be a POC (please God, fellow white people, stop writing your Stepin Fetchit version of Ebonics in the name of authenticity). Conversely, and almost as problematic to my mind, many writers assume that race/ethnicity is irrelevant, so characters can be written as white and then (like the awful colorizing of old movies) given a superficial tint.

Race is a real and meaningful part of who we are, so writing a racially-neutral character and then giving them dark skin or an “ethnic-sounding” name doesn’t allow that character to reflect upon the social realities that shaped their sense of self, particularly how they have been treated by the greater, imperfect world.

These two extremes in how race is treated create a real dilemma for writers who may have the best motives in the world, but motives get you only so far; the success of any writing depends on how it is received by its audience, not by the intentions of the author. So how do you allow race to be a formative part of a character, without reducing that character to a kind of cipher for their demographic in ways that deny the essential and complex personhood of the individual? That’s the challenge for me: not hiding from race but also not allowing it—particularly my white man’s assumptions about what it is—to entirely define the character.

As a writer, I have a great deal of interest in the friction that occurs when some aspect of a person—whether it’s race, gender, profession, interests, tastes, personality, or whatever—is at odds with what might be assumed about them. That’s a rich vein for a fiction writer, especially one like me who has always felt a little between categories, never quite fitting in. But as a white man I understand that there are realms of experience which I do not have, and other experiences which I am socially-coded to ignore or demean. At least, I know it with my head, but not always in my gut. As a literary academic (I’m a Shakespeare professor) as well as a novelist, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the intersection of books and social issues. My home life has allowed me to see those issues in less abstract terms (my wife and son are POC). So while I believe I can understand a little how it feels to be an “outsider,” my gender and race have been, broadly-speaking, assets.

In Japan, for instance, where I lived for a couple of years a quarter century or so ago, I often felt excluded and there were occasional instances (generally involving older people) when I definitely felt the shadow of World War II, but I never felt looked down upon for my race in ways some non-Japanese Asians in the same community did. I have lived in Boston, in Atlanta, and now in Charlotte. In all these places, my Britishness has often triggered a certain “You’re not from round here” wariness or skepticism, but never contempt.

Other people usually assume I’m more sophisticated because of my upbringing (something my Lancashire, working-class school friends would have found hilarious). I’m constantly told that British people all sound smart to Americans, and while that remains baffling to me, I know I benefit from it. While I know what it’s like not to fit in, I’m not constantly judged or demeaned based solely on what people think when they see me. The legacies of colonialism, sexism, and racism are, to this day, power in various forms. Recognizing this has, I think, helped my writing.

My impulse to write characters of color is political and stems from the belief that writers have an obligation to reflect the world they live in. People approach that challenge in a variety of ways, but I feel compelled to try in a small way to redress the historical bias which has taken white (and frequently male, and almost always straight) as the default position. I don’t claim to be an expert, but I am committed to giving diverse characters my very best shot, while simultaneously supporting marginalized writers in the telling of their own stories.

People ask whether I did a lot of research into the lives of people of color before writing this book, and the short answer is: “Consciously? Not much.” As a white man, I don’t want to speak over my wife (who is East Asian) and son’s voices, but I can tell you how my family’s experiences of racism have impacted my writing as well.

Once, while at the grocery store with my mixed-race son, a lady approached me and very politely asked which adoption agency I’d used because she was looking to do the same. As part of an interracial couple I’m alert to these issues and see first-hand that people treat me differently than they do my wife. Some instances, known as microaggressions, are when people talk about the “little stuff”: questions about where she’s “really” from (Chicago), or the pleased relief that she speaks English. Some are more hurtful, as when someone dismissed her Harvard degree on the grounds that “They have quotas for people like you.”

When we first got together I had some very difficult conversations with some well-meaning people who, while professing not to be in any way racist, said, “It’s just the children I worry about.” I hear the fake Chinese some of the local kids start doing when they see us walking the dog in our very white neighborhood, and I’m now talking to my son about how he identifies himself racially in preparation for checking boxes in college applications. Compared to the reality of my wife’s grandfather’s World War II internment (and subsequent loss of all his property), these may seem like minor concerns, but my point is that we’re aware of race all the time. We talk about it all the time.

Life is the apprenticeship you need to be a writer. We all recognize the importance of writing what we know and—particularly in speculative fiction—expanding that sense of knowledge so that we don’t limit ourselves to the prosaically mundane. But what we know is often less about study and research and more about what we have absorbed through daily interactions. I am not a person of color, but the people dearest to me are, and I am made observant and reflective of their lot by love.

Portraying disempowered Otherness on the page is still possible even if you don’t know it (in your gut) as lived experience. You can research it. You can talk to other people about it. Hell, you can see it in the news every day. But writing a POC character when you aren’t one yourself is not the same as writing a profession you know nothing about—plumbing, say—which you can fake your way through by watching a few How To videos on YouTube. In the end, all you can do is try to do it with sensitivity and respect, but—and this is more important—be ready to listen to those better qualified to assess what you’ve done when they tell you you’ve got it wrong. Again, meaning well isn’t enough, and the road to hell really is paved with good intentions.

To return to the Jurassic Park conundrum, however, it’s fair to ask whether the attempt is worth the effort. Indeed, some say that white people writing POC characters or books is itself a form of appropriation, which means there is less room on the shelves for writers of color telling their own stories (there’s a good articulation of this perspective here). But I also think that writing about race (and all the other “isms”) is important because all people have a stake in these conversations, and we need to find ways to discuss such things which break down that sense of our culture as fundamentally siloed, divided, and fractious.

Follow A.J. Hartley on Twitter, on Facebook, and on his website.