Snow. Cold. Winter. New books? Yes!

Check out all the new paperbacks we have coming this Winter!

Coming December 31, 2025

Thornhedge by T. Kingfisher

Thornhedge by T. Kingfisher

From New York Times bestselling author T. Kingfisher, Thornhedge is the tale of a kind-hearted, toad-shaped heroine, a gentle knight, and a mission gone completely sideways.

There’s a princess trapped in a tower. This isn’t her story. Meet Toadling. On the day of her birth, she was stolen from her family by the fairies, but she grew up safe and loved in the warm waters of faerieland. Once an adult though, the fae ask a favor of Toadling: return to the human world and offer a blessing of protection to a newborn child. Simple, right? But nothing with fairies is ever simple. Centuries later, a knight approaches a towering wall of brambles, where the thorns are as thick as your arm and as sharp as swords. He’s heard there’s a curse here that needs breaking, but it’s a curse Toadling will do anything to uphold…

Coming January 07, 2025

To Challenge Heaven by David Weber and Chris Kennedy

To Challenge Heaven by David Weber and Chris Kennedy

The third entry into the New York Times bestselling series, To Challenge Heaven brings another thrilling adventure from the masters of military science fiction, David Weber and Chris Kennedy.

In a universe teeming with predators, humanity needs friends. And fast.

We’ve come a long way in the forty years since the Shongairi attacked Earth, killed half its people, and then were driven away by an alliance of humans with the other sentient bipeds who inhabit our planet. We took the technology they left behind, and rapidly built ourselves into a starfaring civilization. Because we haven’t got a moment to lose. Because it’s clear that there are even more powerful, more hostile aliens out there, and Earth needs allies.

But it also transpires that the Shongairi expedition that nearly destroyed our home planet … wasn’t an official one. That, indeed, its commander may have been acting as an unwitting cats-paw for the Founders, the ancient alliance of very old, very evil aliens who run the Hegemony that dominates our galaxy, and who hold the Shongairi, as they hold most non-Founder species, in not-so-benign contempt. Indeed, it may turn out to be possible to turn the Shongairi into our allies against the Hegemony. There’s just the small matter of the Shongairi honor code, which makes bushido look like a child’s game. We might be able to make them our friends — if we can crush their planetary defenses in the greatest battle we, or they, have ever seen…

Coming January 14, 2025

The Bezzle by Cory Doctorow

The Bezzle by Cory Doctorow

New York Times bestseller Cory Doctorow’s The Bezzle is a high stakes thriller where the lives of the hundreds of thousands of inmates in California’s prisons are traded like stock shares.

The year is 2006. Martin Hench is at the top of his game as a self-employed forensic accountant, a veteran of the long guerrilla war between people who want to hide money, and people who want to find it. He spends his downtime on Catalina Island, where scenic, imported bison wander the bluffs and frozen, reheated fast food burgers cost 25$. Wait, what? When Marty disrupts a seemingly innocuous scheme during a vacation on Catalina Island, he has no idea he’s kicked off a chain of events that will overtake the next decade of his life.

Martin has made his most dangerous mistake yet: trespassed into the playgrounds of the ultra-wealthy and spoiled their fun. To them, money is a tool, a game, and a way to keep score, and they’ve found their newest mark—California’s Department of Corrections. Secure in the knowledge that they’re living behind far too many firewalls of shell companies and investors ever to be identified, they are interested not in the lives they ruin, but only in how much money they can extract from the government and the hundreds of thousands of prisoners they have at their mercy.

A seething rebuke of the privatized prison system that delves deeply into the arcane and baroque financial chicanery involved in the 2008 financial crash, The Bezzle is a sizzling follow-up to Red Team Blues.

Coming January 21, 2025

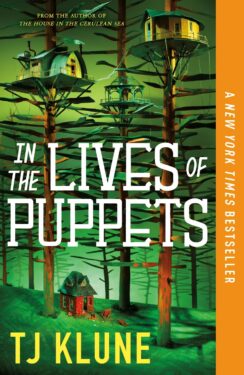

Kinning by Nisi Shawl

Kinning by Nisi Shawl

Kinning, the sequel to Nisi Shawl’s acclaimed debut novel Everfair, continues the stunning alternate history where barkcloth airships soar through the sky, varied peoples build a new society together, and colonies claim their freedom from imperialist tyrants.

The Great War is over. Everfair has found peace within its borders. But our heroes’ stories are far from done.

Tink and his sister Bee-Lung are traveling the world via aircanoe, spreading the spores of a mysterious empathy-generating fungus. Through these spores, they seek to build bonds between people and help spread revolutionary sentiments of socialism and equality—the very ideals that led to Everfair’s founding.

Meanwhile, Everfair’s Princess Mwadi and Prince Ilunga return home from a sojourn in Egypt to vie for their country’s rule following the abdication of their father King Mwenda. But their mother, Queen Josina, manipulates them both from behind the scenes, while also pitting Europe’s influenza-weakened political powers against one another as these countries fight to regain control of their rebellious colonies.

Will Everfair continue to serve as a symbol of hope, freedom, and equality to anticolonial movements around the world, or will it fall to forces inside and out?

Coming January 28, 2025

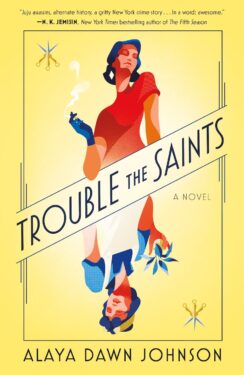

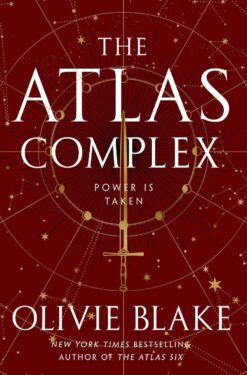

The Atlas Complex by Olivie Blake

The Atlas Complex by Olivie Blake

The Atlas Complex marks the much-anticipated, heart-shattering conclusion in Olivie Blake’s trilogy that began with the New York Times bestselling phenomenon, The Atlas Six.

Only the extraordinary are chosen.

Only the cunning survive.

An explosive return to the library leaves the six Alexandrians vulnerable to the lethal terms of their recruitment.

Old alliances quickly fracture as the initiates take opposing strategies as to how to deal with the deadly bargain they have so far failed to uphold. Those who remain with the archives wrestle with the ethics of their astronomical abilities, while elsewhere, an unlikely pair from the Society cohort partner to influence politics on a global stage.

And still the outside world mobilizes to destroy them, while the Caretaker himself, Atlas Blakely, may yet succeed with a plan foreseen to have world-ending stakes. It’s a race to survive as the six Society recruits are faced with the question of what they’re willing to betray for limitless power—and who will be destroyed along the way.

Exordia by Seth Dickinson

Exordia by Seth Dickinson

Michael Crichton meets Marvel’s Venom in award-winning author Seth Dickinson’s science fiction debut, named one of The New York Times’ Best SFF Books of 2024.

“Anna, I came to Earth tracking a very old story, a story that goes back to the dawn of time. It’s very unlikely that you’ll die right now. It wouldn’t be narratively complete.”

Anna Sinjari—refugee, survivor of genocide, disaffected office worker—has a close encounter that reveals universe-threatening stakes. Enter Ssrin, a many-headed serpent alien who is on the run from her own past. Ssrin and Anna are inexorably, dangerously drawn to each other, and their contact reveals universe-threatening stakes.

While humanity reels from disaster, Anna must join a small team of civilians, soldiers, and scientists to investigate a mysterious broadcast and unknowable horror. If they can manage to face their own demons, they just might save the world.

Coming February 25, 2025

The Last Colony by John Scalzi

The Last Colony by John Scalzi

From New York Times bestselling author John Scalzi, comes The Last Colony, the third book in the Old Man’s War series, now for the first time in trade paperback with a new introduction by the author.

Retired from his fighting days, John Perry is now village ombudsman for a human colony on distant Huckleberry. With his wife, former Special Forces warrior Jane Sagan, he farms several acres, adjudicates local disputes, and enjoys watching his adopted daughter grow up.

That is, until his and Jane’s past reaches out to bring them back into the game — as leaders of a new human colony, to be peopled by settlers from all the major human worlds, for a deep political purpose that will put Perry and Sagan back in the thick of interstellar politics, betrayal, and war.

Projections by S. E. Porter

Projections by S. E. Porter

S. E. Porter, critically-acclaimed YA author of Vassa in the Night, bursts onto the adult fantasy scene with her adult novel that is sure to appeal to fans of Jeff VanderMeer and China Mieville.

Love may last a lifetime, but in this dark historical fantasy, the bitterness of rejection endures for centuries.

As a young woman seeks vengeance on the obsessed sorcerer who murdered her because he could not have her, her murderer sends projections of himself out into the world to seek out and seduce women who will return the love she denied—or suffer mortal consequence. A lush, gothic journey across worlds full of strange characters and even stranger magic.

Sarah Porter’s adult debut explores misogyny and the soul-corrupting power of unrequited love through an enchanted lens of violence and revenge.

Coming March 11, 2025

Twice Lived by Joma West

Twice Lived by Joma West

Torn between two families and two lives, a troubled teen must come to terms with losing half their world.

Two Worlds. Two Minds. One Life.

There are two Earths. Perfectly ordinary and existing in parallel. There are no doorways between them, no way to cross from one world to another. Unless you’re a shifter. Canna and Lily are the same person but they refuse to admit it. Their split psyche has forced them to shift randomly between worlds – between lives and between families – for far longer than they should. But one mind can’t bear this much life. It’ll break under the weight of it all. Soon they’ll experience their final shift and settle at last in one world, but how can they prepare both families for the eventuality of them disappearing forever?

Twice Lived is a novel about family and friendships, and about loss and acceptance, and about the ways we learn to deal with the sheer randomness of life..

Coming March 18, 2025

The Martian Contingency by Mary Robinette Kowal

The Martian Contingency by Mary Robinette Kowal

Mary Robinette Kowal returns to Mars in this latest entry to the Hugo and Nebula Award-winning Lady Astronaut series.

“Kowal masters both science and historical accuracy in this alternate history adventure.”—Andy Weir, author of The Martian, on The Calculating Stars

Years after a meteorite strike obliterated Washington, D.C.—triggering an extinction-level global warming event—Earth’s survivors have started an international effort to establish homes on space stations and the Moon.

The next step – Mars.

Elma York, the Lady Astronaut, lands on the Red Planet, optimistic about preparing for the first true wave of inhabitants. The mission objective is more than just building the infrastructure of a habitat – they are trying to preserve the many cultures and nuances of life on Earth without importing the hate.

But from the moment she arrives, something is off.

Disturbing signs hint at a hidden disaster during the First Mars Expedition that never made it into the official transcript. As Elma and her crew try to investigate, they face a wall of silence and obfuscation. Their attempts to build a thriving Martian community grind to a halt.

What you don’t know CAN harm you. And if the truth doesn’t come to light, the ripple effects could leave humanity stranded on a dying Earth…

The Vampire Tapestry by Suzy McKee Charnas; introduction by Nicola Griffith

The Vampire Tapestry by Suzy McKee Charnas; introduction by Nicola Griffith

Tor Essentials presents new editions of science fiction and fantasy titles of proven merit and lasting value, each volume introduced by an appropriate literary figure.

The Nebula Award-finalist reinvention of the vampire novel, described as a “masterpiece” by Guillermo del Toro.

Edward Weyland is far from your average vampire: not only is he a respected anthropology professor but his condition is biological — rather than supernatural. He lives discrete lifetimes bounded by decades of hibernation and steals blood from labs rather than committing murder. Weyland is a monster who must form an uneasy empathy with his prey in order to survive, and The Vampire Tapestry is a story wholly unlike any you’ve heard before.

With a new introduction by Nicola Griffith, author of Spear.