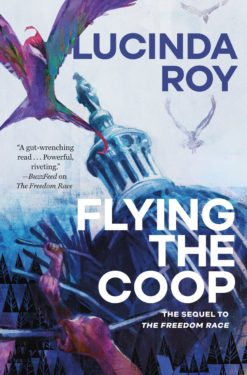

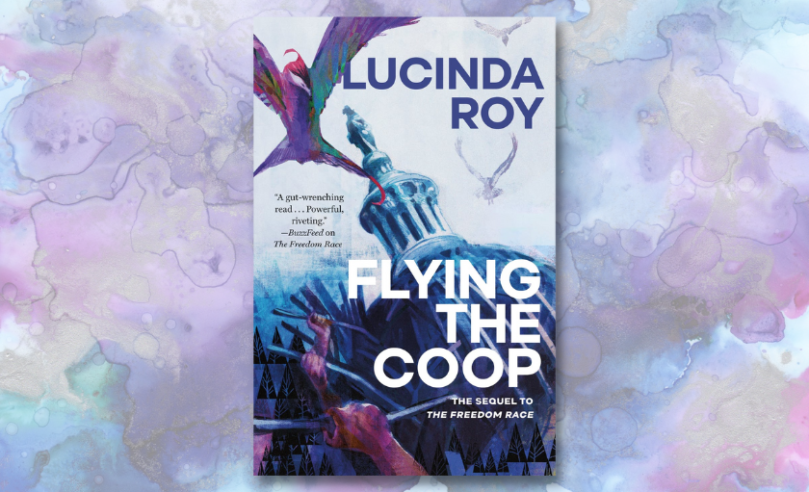

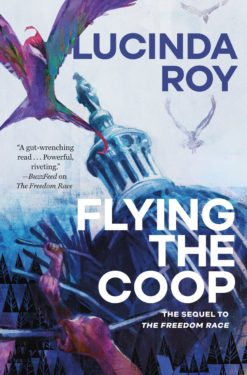

“I didn’t want to write about why the caged bird sings; I wanted to write about how the caged bird flies.” –Lucinda Roy, author of Flying the Coop

“I didn’t want to write about why the caged bird sings; I wanted to write about how the caged bird flies.” –Lucinda Roy, author of Flying the Coop

Lucinda Roy’s speculative dystopia Dreambird Chronicles trilogy that began with The Freedom Race and continues with Flying the Coop depicts a haunting vision of future America. Despite the horror, elements of Black history are woven into the world-building. Check out this essay from Lucinda Roy!

By Lucinda Roy

When I wrote The Freedom Race, the first volume in my Dreambird Chronicles speculative trilogy, I was faced with some burning questions I had to address. And now, with the publication of Flying the Coop, the second volume, it’s clear that these questions have shaped the series in ways I couldn’t have imagined when I first conceived of the story over a decade ago.

Among the questions I had to address were these. If, in the aftermath of a second Civil War, slavery returns to a large section of a trifurcated country, a place now known as the Disunited States, how would enslaved characters retain their humanity? What would inspire them and give them joy?

In Flying the Coop, set primarily in D.C., I depict a future Disunited States still reeling from the aftermath of a second civil war known as the Sequel. The U.S. has been blown apart by conflict, climate insecurity and pandemics. Its primary autonomous regions are the Eastern and Western SuperStates along the coasts; independent cities like D.C., Atlanta, and Chicago; and the Homestead Territories in parts of the South and Midwest, which adhere to a segregationist ideology modeled on the old plantation system. It is chilling to see how much closer we have moved toward a second civil war since I first envisioned the series all those years ago.

Although I knew I could never minimize the horrors of slavery, I didn’t want to write about suffering without also exploring the miracle at the heart of enslavement. The miracle is this: in the face of unspeakable suffering, the enslaved survived. I didn’t simply want to catalogue a litany of suffering, especially when slavery has been handled movingly by writers in the past; instead, I wanted to celebrate this miracle of survival in a way that could be embodied in something concrete. But how?

I hadn’t expected that one of the answers to these questions would be a game the enslaved invent to honor those who fought against racism and slavery. The game was absent in the first iterations of this story. After a while, it became peripheral. Then it was something played by a few of the male characters. Only later did the game take shape as a central force and touchstone in the novels.

The game, called simply Fly the Coop, serves as a refuge, an inspiration, a site of rebellion, and a deeply ironic commentary on the apartheid system, a system that reclassifies “imported laborers” from Africa, and other people of color who don’t have the documentation to claim indigenous status, as botanicals—or, more colloquially, as seeds. In one fell swoop, this heinous reclassification strips laborers of their rights and privileges under the law and consigns them to a life of servitude in the Homestead Territories. The botanical classification cages them and holds them captive. But there’s a catch: it also amplifies their yearning for Freedom, a concept the so-called seeds revere and therefore always capitalize. This quintessential conflict lies at the heart of Fly the Coop—a game of contradictory impulses suffused with the tension slavery produces. If characters can’t literally escape the cage, can they escape it figuratively? Can they fly the coop in plain sight of those who hold them captive?

Designing a game played in a future Disunited States wasn’t easy. It had to be exciting enough to entice spectators and meaningful enough to players that they would be willing to risk injury or even death to play it. Having taught many college athletes in the past, I was aware of the critical role competitive sports plays in the U.S., and how team sports are often hinged to notions of ownership. Even so, I didn’t want it to be only a game imposed by oppressors on victimized people. Though this kind of simplified, top-down approach to game design in speculative fiction has proven popular, it seemed more plausible that this game would grow organically out of the soil of the setting. The characters’ yearnings would design it. What I had to do as a writer, therefore, was listen to them.

I had a few lights to steer by. I knew, for example, that whatever game I invented would need to be dangerous and uplifting, based in reality but dependent on illusion, part satirical commentary and part go-for-broke spectacle, part battle and part beauty. One other thing I knew for certain: the game had to reflect the culture that produced it, which meant it had to pay tribute to the phenomenon of storytelling and the persistent power of dreams.

Fly the Coop draws from tropes prevalent in stories by those of us who trace our roots back to the African Diaspora. But it also draws upon feelings of confinement felt by women and by disadvantaged men throughout the centuries. Prohibited from elevating themselves in any meaningful way, seeds invent a game that not only permits elevation but which actually enables them to “fly.”

A cross between a flying circus, a gladiatorial Colosseum battle, and cage fighting, Fly the Coop embodies the famous Flying Africans myth—the idea that people rose up spontaneously to escape slavery and flew a way back home. Protagonist Jellybean “Ji-ji” Lottermule recalls what Uncle Dreg, revered by seeds as a Tribal wizard and prophet, told her about it:

Uncle Dreg used to tell Ji-ji that the coop was equally symbolic to seeds and steaders. To seeds it was a reminder that flight was possible; to steaders it emphasized the inescapable supremacy of the cage…. What mattered to Ji-ji was that the planting flying coop was the one place where her dreams were more powerful than her yearning.

The fly coop houses a multi-tiered, high-tech fly cage where battles are waged between pro teams. In these circus-like arenas, seeds and former seeds battle for supremacy, using weapons and daring athletic skill. Between battles, they vault from trampolines, fly on trapezes, and shimmy up hope-ropes, striving to seize a tactical advantage by climbing higher in the cage than their opponents.

The game is played inside an arena called a coop. Fly coops on plantings are modest in size—more like small circus tents. But the pro coops in the cities are massive, comparable in size to American football arenas. In Flying the Coop, the newly constructed Dream Coop in D.C. is an impressive feat of engineering, with a control booth and special effects teams, intricate projection systems, and a center ring that opens up like the mouth of a monster to reveal terrifying surprises which shock the tens of thousands of flyer fans in the arena and those watching at home.

As is the case in other pro coops around the country, much of the equipment inside D.C.’s Dream Coop honors Civil Righters, Middle Passengers, and other inspiring figures from history. There are King-spins and Harriet Stairs, Douglass Pipes and Rosa Parks Perches, ‘Bama’s Dramas (state-of-the-art trampolines), Ali Stingers, Baldwin Beams, DuBois’ Toys, Biles Trials, an enormous Ellison Wheel players can be invisible inside, and a smaller Wheatley Wheel flyers can leap onto to escape attack. The crowning glory in the coop is the Jim Crow Nest suspended from the dome, the largest nest of its kind and the exclamation point in the seeds’ satirical commentary on oppression.

The athletes who fly the coop select their own flyer names: Tiro the Pterodactyl, Angel Birdgirl, Laughing Tree, Marcus Aurelius (a.k.a. the Thinker), and X-Clamation, to name a few. Naming becomes a rite of passage for characters in these books, some of whom go by multiple names. Many decades ago, not long before he died, my Jamaican Maroon father selected another name for himself and his biracial offspring. Even though he had so little money (his paintings, sculptures and novels weren’t selling, and he’d been fired from his job at a Brillo factory for attempting to start a union), he paid to change his name legally. He told my mother he didn’t want to have a name that could be traced back to plantation owners. As a proud Black man, he wanted his name to be his creation alone. Names matter. They don’t simply tell us who we are, they can also reveal who we most want to be.

Fly the Coop’s arbiters are an acknowledgement of the brutal penal system in the Territories. The intimidating Jury of Judges awards points for victories in battle and for acrobatic skill on the coop equipment. The twelve black-robed judges often mete out justice arbitrarily, influenced by the sentiments of spectators and coop owners. The person who “conducts” the coop is known as the coopmaster. In D.C.’s famous Dream Coop, the maestro is also known as the Dream Master, a fitting title for a character named Amadeus “I’m-a-God” Nelson, who was once an outcast Serverseed and is now the most powerful Black Man in the city.

Not all of the enslaved are enamored with the fly coop. In The Freedom Race, protagonist Ji-ji Lottermule’s mother rails against it and against Tiro, the reckless fly-boy her daughter loves:

“Swinging around in that coop like some brainless bird! Those vulgar wings on his shirt! Using cheap tricks to fly! An illusion—is it not so? A game steaders play to pacify seeds—trick us into forgetting we can never fly from here. They’ve snatched our history like they snatched us!”

Yet most of the seeds find the coop inspiring, a sentiment Tiro describes as he sits inside the Dream Coop fly cage on a Rosa Parks Perch and speaks to his dead brother:

“We got an Ellison Wheel big as a building, largest wheel of its kind. It’s got these paddles function as landing platforms an’ springboards. With a touch of a button, Coopmaster Nelson can expand and contract it, spin it fast, or spin it slow. Can make the whole goddam wheel invisible, pretty much, if he wants.”

Though readers unfamiliar with figures in Black history may not recognize the allusion to Ralph Ellison’s famous novel Invisible Man, or know who is being referenced in the architecture and equipment in these fly coops, what is far more important is how the game houses the dreams of the characters. Played inside a gargantuan bird cage, where mystery and magic combine to thrill those who invest in a dream, the dangerous game of Fly the Coop reminds characters who suffer under the yoke of enslavement that liberty and justice—the most precious gifts a nation possesses—have never been easily won. For enslaved people, the yearning to fly the coop is eternal.

Novelist, poet, and memoirist Lucinda Roy is the author of the speculative novel The Freedom Race and three collections of poetry, including Fabric: Poems. Her early novels are Lady Moses, a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection, and The Hotel Alleluia. She also authored the memoir No Right to Remain Silent: What We’ve Learned from the Tragedy at Virginia Tech. Her latest book Flying the Coop, is now on sale.

Order Flying the Coop Here:

We love space operas. LOVE. But we have questions.

We love space operas. LOVE. But we have questions.

That’s a hard question, not because I’m having trouble thinking of an answer, but because I’m having trouble picking from the dozens of answers that spring to mind.

That’s a hard question, not because I’m having trouble thinking of an answer, but because I’m having trouble picking from the dozens of answers that spring to mind.