Every Tor Book Coming This Winter

We’re closing in on the end of 2020 (BIG SIGHES OF RELIEF), and with that comes some brand new books to curl up with this season. Check out which ones are hitting shelves near you this winter here.

We’re closing in on the end of 2020 (BIG SIGHES OF RELIEF), and with that comes some brand new books to curl up with this season. Check out which ones are hitting shelves near you this winter here.

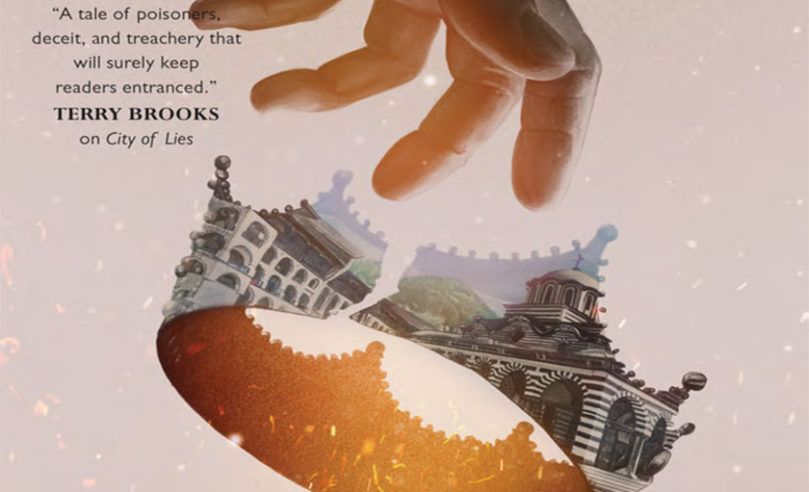

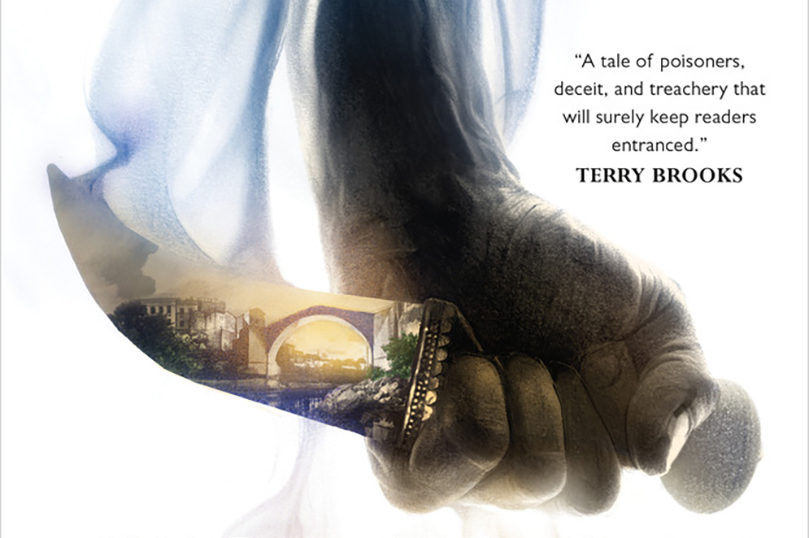

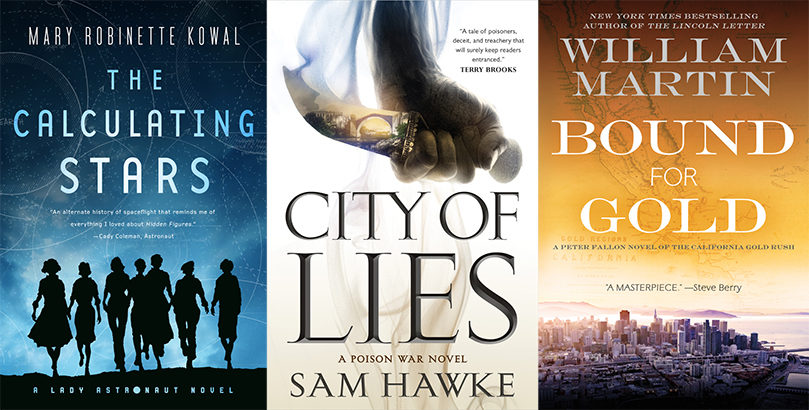

Moving from poison and treachery to war and witchcraft, Sam Hawke’s Poison Wars continue with Hollow Empire, a fabulous epic fantasy adventure perfect for fans of Robin Hobb and Naomi Novik. Poison was only the beginning. The deadly siege of Silasta woke the ancient spirits, and now the city-state must find its place in this…

We’re dreaming of fall weather at Tor…the changing of colors, the crackle of a bonfire, the tastes of our favorite fall foods. And we can hardly contain ourselves as we wait for our fall books to finally make their way into our hands. Check out which books are coming to shelves near you this fall here!

Get the ebook of City of Lies by Sam Hawke for just $2.99!

We’ve been celebrating Fearless Women all year, and we asked some of the authors who are crafting elaborate worlds and nuanced female characters to chat with us about how they first fell in love with genre storytelling. How and when did you first fall in love with science fiction and fantasy? Jacqueline Carey:…

Do you have what it takes to be a proofer, like Jovan in City of Lies? Find out if your palette is up to the task in our quiz!

Meet the #FearlessWomen: Kalina from City of Lies by Sam Hawke!

New from Mary Robinette Kowal, Sam Hawke, William Martin, and others!

Author Sam Hawke tackles a big question: how does sci-fi and fantasy—and her novel City of Lies—uniquely explore gender?

Fantasy novels are full of swords and magic, with big battles, duels, and assassins. One thing that doesn’t turn up as often as it should? Poison. Luckily, there are always exceptions the rule, like in these 7 novels.