Story ideas can come from anywhere, but what does it take for it to flourish into a full-blown novel? Mirah Bolender, author of the Chronicles of Amicae series, joins us to talk about her inspiration for the series, its publishing evolution, and more. Check it out here!

Story ideas can come from anywhere, but what does it take for it to flourish into a full-blown novel? Mirah Bolender, author of the Chronicles of Amicae series, joins us to talk about her inspiration for the series, its publishing evolution, and more. Check it out here!

By Mirah Bolender

It’s pretty common knowledge that story ideas can spark just about anywhere. Anyone writing probably has computer documents, notebooks, and paper scraps overflowing with pieces of inspiration. It’s hard sometimes to know which of those will actually keep your attention and grow—sometimes the ones you’re initially passionate about fall to the wayside, and something random you picked up on a whim turns into a monster of a draft.

I recently found my original idea for the Chronicles of Amicae: less than two hundred words jotted down in a junk file on my computer, forming the vaguest of outlines. While I can see the roots of the final story in there, it’s also laughably different! It was steampunk. It had very heavy The BFG vibes. It was weird. At the time I was a college student participating in a writing workshop; the professor was assigning us all sorts of prompts to combine together, and I was having a ball with those already. I thought to myself, why not use this weird idea for the latest prompt? The prompt in question was “a day on the job,” but this professor was also notorious for adding in conditions from whatever he was reading. In this case, he had just finished House of Leaves—we had to create separate but connecting narratives in layers of footnotes. The outcome became chapter one. While the footnotes never made it to the final product (readers will probably thank me for that), the paranoia and subplots from them were still material that became vital plot points for the rest of the series.

Characters are key to every story, and most of the time I come up with characters before I figure out anything else. In this case I came up with the clever and mysterious Sweeper Mentor, but I didn’t want to write from his perspective because 1) clever mentors already know things instead of unraveling them for an audience, and 2) keeping a mentor clever and mysterious when you’re writing inside his head is a very difficult task. I needed a protagonist, but I had no idea what kind of person she’d be. For this I turned to my favorite type of characterization: a pinball method. Basically, if you’ve got one solid character, you bounce the new one off of it and figure them both out based on reactions—after all, if you know what you want the solid one to say, what can prompt them to say it? I bounced the blank Sweeper Apprentice off of the Mentor, what immediately came out was sass, and I said to myself, Ah, yes, I like this one. Boom, I had “Laura” instead of “Apprentice.”

When it comes to plot, I’m absolutely a “pantser”: I “fly by the seat of my pants.” When push comes to shove I can be a hybrid “plantser” by including outlines, but the pinball method hits me here, too—I’ll write a scene, which will then ricochet into something completely unplanned because oh no that gives me another cool idea to weave in—and so it goes. I’m also kind of a story magpie because I’ll toss in recycled bits from my old work or other interesting things I’ve seen recently. If those elements bounce off the existing material right, they stay! Otherwise they get pulled out and thrown in the recycle pile again. For example, the character Okane’s appearance, his personality, and his physical inability to say the word “you” are all harvested from different pieces of old stories that ended up working perfectly into the established magic system here, and became key pieces of this series’ plot.

Writing a series is difficult. You probably already guessed that when pinball is so prominent in my writing process, but even after that stage is over it gets complicated. Imagine the series is a skyscraper. Your solid draft of book one is the ground level up to the fifteenth floor; your early draft of book two forms the next section up; and the mostly written version of book three is wavering up on top in the wind. Edits happen. Maybe they’re tiny edits, but they’ve shifted the foundations and suddenly everything on top is off balance. You keep the bones of book two’s draft but with much heavier edits. Suddenly everything you had for book three makes no sense, it doesn’t work, why did you even have a draft for book three? (The answer is that you should absolutely have something to go on even if it’s an outline). Edits across the books can be so dramatic, there are even two characters in book three that have completely swapped personalities from their original versions! I’ve had the great luck of working with an editor who’s been enthusiastic about my story at every turn and never once suggested a change that didn’t make the narrative stronger, so while it can feel hectic and rushed during edits, it’s also something I’ve been able to step back and marvel at once I’m done.

Writing a series is also a lot of fun. You become attached to the world and characters that you’ve created. After you’ve explained the basics of the magical society and forged the relationships during book one, you don’t have to leave! Everything is broken in already. You don’t have to reiterate the basics, just launch into the new situation! I always had a series in mind, because when I got invested enough to write the story, I kept thinking of all the different situations possible for those characters and how they all couldn’t fit into one book. If you’re going to invest your time, why not put in serious dedication? Case in point: my original thought for Chronicles of Amicae was more like five books. My editor and I took a different course and ended up at the far stronger three. We’re already dealing with politics, mobs, crusading cities, secret magical communities, and man-eating nightmare monsters living like hermit crabs in the equivalent of magical rechargeable batteries. There was so much already; snippets of other Sweeper plotlines had to be filed away to be recycled into future products.

Honestly, it still amazes me that I’m published. Every time that I remember I’ve seen my books on a bookstore shelf or available online, I have to lay down and try not to scream with excitement. It’s so cool that I’ve been able to do what I love professionally. No matter what happens to me in life, no one can take away the fact that I have been published. There are so many ideas, so many things I’ve tried writing…sometimes it’s strange which ones keep my attention long enough to become finished drafts. When I first jotted down those two hundred words, I never would’ve guessed they’d grow into something this big. It’s been a wild ride, but it’s also been a lot of fun.

Mirah Bolender is the author of the Chronicles of Amicae. The final book in the trilogy, Fortress of Magi, is on sale from Tor Books on April 20, 2021.

Pre-order Fortress of Magi

The Chimera series by Cate Glass has officially come to a close, but we’re continuing the adventure with a very special look back at the series with author Cate Glass! Check out her guest post as she talks about writing the series, developing the story, and more.

The Chimera series by Cate Glass has officially come to a close, but we’re continuing the adventure with a very special look back at the series with author Cate Glass! Check out her guest post as she talks about writing the series, developing the story, and more.

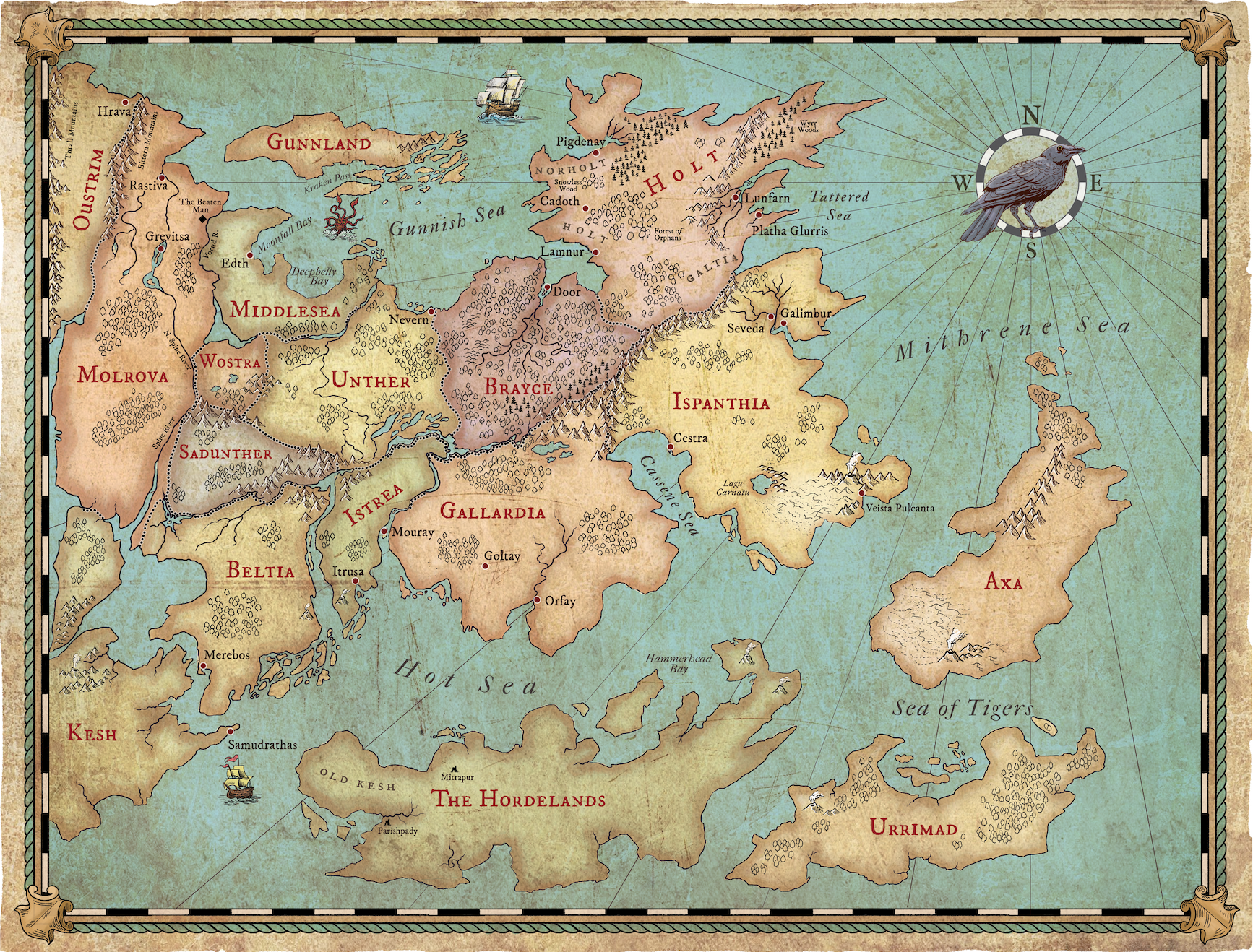

Science fiction and fantasy books take us to all types of different worlds: forests, deserts, even the stars. Michael Johnston, author of

Science fiction and fantasy books take us to all types of different worlds: forests, deserts, even the stars. Michael Johnston, author of

There are so many different type of protagonists out there, from the sweet cinnamon roll hero to the tortured, tragic titular character. But one of our favorites? The chaotic problem protagonist. Read on as Everina Maxwell, author of

There are so many different type of protagonists out there, from the sweet cinnamon roll hero to the tortured, tragic titular character. But one of our favorites? The chaotic problem protagonist. Read on as Everina Maxwell, author of

Aspiring authors, listen up! Arkady Martine, historian, city planner, and Hugo award-winning author of space operas

Aspiring authors, listen up! Arkady Martine, historian, city planner, and Hugo award-winning author of space operas

Cixin Liu is the New York Times bestselling author of

Cixin Liu is the New York Times bestselling author of