opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

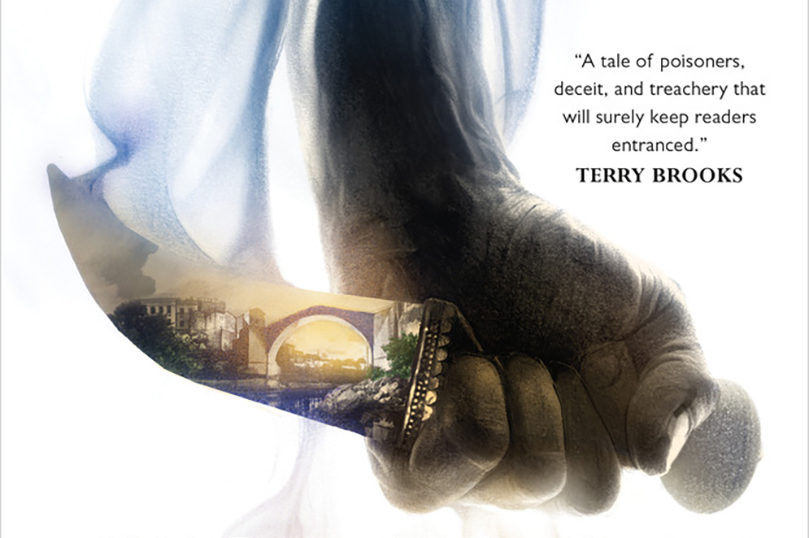

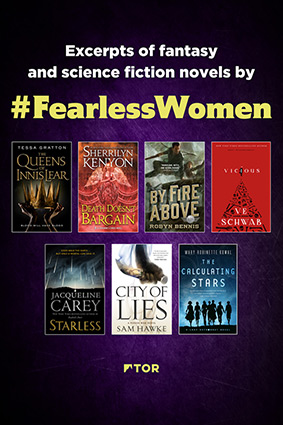

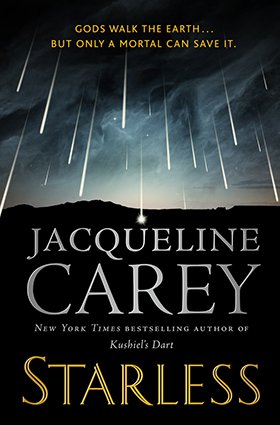

Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today we’re featuring an excerpt from Starless, a new epic fantasy by Jacqueline Carey where gods live among us, but only a mortal can save the world.

Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today we’re featuring an excerpt from Starless, a new epic fantasy by Jacqueline Carey where gods live among us, but only a mortal can save the world.

Let your mind be like the eye of the hawk…

Destined from birth to serve as protector of the princess Zariya, Khai is trained in the arts of killing and stealth by a warrior sect in the deep desert; yet there is one profound truth that has been withheld from him.

In the court of the Sun-Blessed, Khai must learn to navigate deadly intrigue and his own conflicted identity…but in the far reaches of the western seas, the dark god Miasmus is rising, intent on nothing less than wholesale destruction.

If Khai is to keep his soul’s twin Zariya alive, their only hope lies with an unlikely crew of prophecy-seekers on a journey that will take them farther beneath the starless skies than anyone can imagine.

Starless will be available on June 12th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

ONE

I was nine years old the first time I tried to kill a man, and although in the end I was glad my attempt failed, I had been looking forward to the opportunity for quite some months. That is only natural, I think, when one is raised as I was; although as I grow older, I am less and less sure what that means. All things proceed from nature—if one thing alters the course of another’s growth, is that not yet within the accordance of nature? A vine trained to climb a trellis remains a vine.

And I am Khai, and remain myself, whatever that means.

It is a good name; strong and bold, a name like the sound of a desert hawk’s cry. A fitting name for a child of the desert; a fitting name for a child whose destiny was determined by a single feather.

But that is not the whole truth, and Brother Saan, who is our Seer and the wisest among us, says truth must be laid bare, as clean as a corpse flensed to the bone by Pahrkun the Scouring Wind.

So.

This was the truth as I knew it: Nine years ago in the realm of Zarkhoum, such an event transpired as had not taken place for a hundred and fifty years. At the precise moment that Nim the Bright Moon obscured Shahal the Dark Moon, a child was born to the House of the Ageless, whose members are also known as the Sun-Blessed.

The priestesses of Anamuht the Purging Fire are great keepers of records, and the lore of the realm holds that when a child of the royal house is born during a lunar eclipse, so too is his or her shadow.

I was not the only such child born at that precise moment. According to Brother Saan, the priestesses of Anamuht spent almost a year consulting midwives across the length and breadth of Zarkhoum. In the end, they discovered thirteen of us.

Hence, the feather.

I remember it.

I do not remember the mother or father to whom I was born. I do not know if I was high-born or low, or if I was born to the fierce desert nomads who acknowledge no rank save that which personal honor won in their own vendettas accords them. Brother Saan does not know either, but he tells me that the priestesses of Anamuht will have that information recorded in their scrolls, and I may seek it for myself when I come of age, if the Sun-Blessed princess who is the light to my shadow allows it.

Perhaps I shall; perhaps not. After all, does it matter? In the end, I was the one who was chosen.

A feather.

It took place in the portion of the Fortress of the Winds that we call the Dancing Bowl; although that I do not remember, I know only because I have been told. It is a hard, stony basin which the men use for sparring practice. There are three tunnels that open onto its sloping sides, and many more riddling the cliffs that rise to tower over it. High above the basin, there is a thin stone bridge that arches across it—nothing built by human hands, but a structure etched into being by Pahrkun the Scouring Wind some thousands of years gone by.

I know it well, for I have crossed it many times. I have felt its faint tremor beneath my bare feet; I have felt the wind tug at my garments, threatening to unbalance me. Ah, but the wind . . . I must learn to embrace it.

And so I shall, for I am pledged to Pahrkun the Scouring Wind, and it is all because of the feather.

I remember.

I do.

There were thirteen of us, all babes. Thirteen carpets were laid on the floor of the Dancing Bowl; thirteen babes were set upon the carpets. I do not remember that part, but Brother Saan has told me many times. It was midmorning in high spring, and the heat would have been rising like an oven, only a slight breeze swirling in the basin. I can imagine it well. Atop the arched bridge, Brother Saan opened his hand and let fall a single hawk feather.

When I close my eyes, I can see it still: blue sky and a lone feather, a pale brown with darker brown stripes. I see it fall, drifting on the breeze, turning in circles as it falls. I see the breeze carry it west, then north; east, then south. I see the edge of the vanes catch the light like the honed edge of a blade, I see the hollow shaft glow with a milky translucence.

Brother Saan watched from atop the bridge. The figures of the other brothers and a cluster of veiled priestesses in their bright red robes dotted the tunnel mouths above the Dancing Bowl, waiting, waiting, to see where the feather would fall, which babe would be marked by Pahrkun’s favor, chosen to be the shadow to the bright Sun-Blessed princess in the faraway city of Merabaht.

Along the walls of the Dancing Bowl, the families watched and waited to see who among them would return to their far-flung homes less one babe, bragging of the honor bestowed upon them.

The feather drifted and drifted, circling down above me. I waved my hands in the air and caught it in one chubby fist.

A great cheer went up; that, too, I do not remember.

But I remember the feather. I have it still.

And so it came to pass that I was raised in the Fortress of the Winds by the Brotherhood of Pahrkun, raised to be a warrior.

Of course, at nine years of age, I was not yet fully versed in the traditional weapons of the brotherhood. I lacked the strength to effectively wield the curved sword known as yakhan, or wind-cutter, as well as the three-pronged kopar that served as a weapon of both offense and defense, but that, I was promised, would come in time. I was quick and wiry, hardened to the elements by going shirtless and barefoot in summer and winter alike, and I could take down a mountain goat with a single, swift blow to the jugular with the slender dagger that had been given me on my seventh birthday.

And so, when a caravan escorting a supplicant to attempt the Trial of Pahrkun appeared on the horizon, I begged to be allowed to take part. Understand that there was no malice in it. This was simply our way in Zarkhoum; and indeed, I believed that there was both purpose and mercy in it. It was a harsh mercy, but then the desert is a harsh place.

The nature of the Trial of Pahrkun was this: Any man convicted of an offense deserving of execution could choose instead to undertake the trial, upon whence he would be escorted by the Royal Guard across the deep desert to the Fortress of the Winds. At the entrance to the fortress—which, like the bridge above the Dancing Bowl, is no man-made edifice, but a vast series of caverns and tunnels—the supplicant would strike the sounding-bowl and announce his intention.

To pass the trial, the supplicant had to do but one thing: make his way past three brothers in the Hall of Proving. If he succeeded in emerging alive into open air, he was reckoned scoured of his sins by Pahrkun, accepted into the brotherhood, given a new name and a new life.

Very few men attempted this.

Even fewer succeeded, for the fighting skills of the brothers who were born into this warrior caste and pledged to its service as young men—though none so young as I—were not only honed by decades of practice and centuries of tradition, but augmented by the skills of those few who did succeed.

There was much debate around the supper table the evening before the supplicant’s arrival.

“Khai is young,” Brother Drajan said in his slow, implacable manner. He served as cook to the brotherhood, and although I was often grateful for his considered ways, on that occasion it made me impatient. He glanced at me out of the corner of his eye, one corner of his mouth tugging downward in an apologetic grimace. “Let him be a boy while he may. It is too soon for him to wrestle with mortality.”

Brother Jawal made a lightning-quick gesture as though flicking away a fly. “Are we raising a warrior or not? Death is no respecter of age.”

“Therein lies my concern.” Elderly Brother Ehudan, who taught me my characters and numbers, knit his brow. “What would come to pass if the shadow of the Sun-Blessed met an untimely demise?”

Everyone looked to Brother Saan, including me.

Brother Saan’s face was tranquil. He was old, too; older than Brother Ehudan, although it seemed to me that age had visited him in a different way. There was nothing crabbed or querulous about him, only a deep stillness none of us could yet emulate. “Khai might die in a dozen ways in our care before the princess comes of age,” he said mildly. “One wrong step in the heights, and he would plunge to his death. We cannot allow that fear to hobble us.”

I stifled an indignant protest at the notion that I might perish due to a careless misstep.

Brother Saan’s gaze rested on me. “You are eager to undertake this challenge?”

I placed my palms together and touched my thumbs to my brow in a gesture of respect. “I am, Elder Brother.”

“Then it shall be so,” he said. “On the morrow, Khai will take the third and final post in the Hall of Proving.”

My heart quickened. “Thank you, Elder Brother!”

“It is no gift I give you, but a grave charge,” Brother Saan said to me. “Tomorrow, a man’s life hangs in the balance. It is Pahrkun who decides his fate; know that you are but an instrument.”

I touched my brow again. “Yes, Elder Brother.”

Brother Saan’s eyelids crinkled. “What is a warrior’s first and greatest weapon, young Khai?”

“It is his mind, Elder Brother,” I said.

“Very good.” Rising from the table, Brother Saan laid a hand on my shoulder. “Conduct yourself with honor.”

I inclined my head. “Always, Elder Brother.”

My sleep that night was restless. I rose at dawn to offer my prayers in the privacy of the small cavern that was my bedchamber; four genuflections for Zar the Sun, Nim the Bright Moon, Shahal the Dark Moon, and Eshen the Wandering Moon; two genuflections for Anamuht the Purging Fire and Pahrkun the Scouring Wind; and at last four genuflections for the four great currents, east, west, north, and south.

Brother Jawal poked his head in the opening of my cavern. “Are you done?” he inquired. “Come, let’s get a look at this supplicant.”

I scrambled to my feet. “Yes, brother.”

Atop the western lookout, the wind was brisk and buffeting. I stood beside Brother Jawal, knees flexed to maintain my balance.

Let your mind be like the eye of the hawk.

So Brother Saan had taught me. I gazed at the party making its way toward the Fortress of the Winds. Six men in the crimson and gold silks of the Royal Guard riding hardy, sure-footed steeds. One man in the center of them; a portly fellow clad in rich brocade robes, several purses and a long sword with a gem-encrusted pommel dangling from his waist-sash. Their shadows stretched westward behind them.

Brother Jawal made a disparaging sound. “A merchant,” he said in a dismissive tone. “Soft and rich. Like as not, he’ll try to bribe us.”

I was shocked. “Is that permitted?”

“No.” Brother Jawal shook his head. “But that’s the way city folk are.”

I supposed it must be true, and I shook my head too at the folly of city folk. To think that one could bribe us!

It made me wonder, though, what the princess would be like. I thought of her often; the light to my shadow. It was the first time in recorded history that a daughter of the Sun-Blessed had been born with a shadow. Zariya was her name; all of the Sun-Blessed bear the name of the Sun in their own names. Zariya of the House of the Ageless, the seventeenth child born to His Majesty King Azarkal, who had reigned for three hundred years; the third child born to his fifth wife. Sun-Blessed, because Zarkhoum lies the farthest east of any nation beneath the starless sky; the House of the Ageless, because the sacred rhamanthus seeds that are quickened by Anamuht the Purging Fire bestow great longevity upon its members.

These things I knew because Brother Ehudan taught them to me, but I could not imagine what such a person would be like. I knew the desert and hawks and wind; I did not know cities.

I imagine there must be color, a great deal of color, like the silks the Royal Guards wore; or like the robes the fat merchant wore, all blue and green with gold stitching, robes that were wholly unsuited for the desert.

As they drew near, I saw that he was sweating in the heat, the poor foolish fellow. “Why would he wear such garments?” I asked Brother Jawal.

He shrugged; he was desert-born, a son of one of the nomadic tribes, and pledged to Pahrkun’s service by birthright, not trial. “Among the city folk, such garments indicate wealth and status.”

I squatted on my haunches, leaning over the ledge of the lookout. “I wonder what his crime was.”

Brother Jawal shrugged again. “Whatever it was, he’ll meet his final judgment today.”

“Or not,” I reminded him.

He laughed and caressed the hilt of his yakhan. “Oh, I think a mighty wind is coming for this fat man, little brother. I’ve been given the first post.”

I glanced over my shoulder toward the east. Beyond the peaks and valleys of the Fortress of the Winds lay the deepest desert. It was the domain of the Sacred Twins, for there Pahrkun stalked the sands, raising them into a killing gyre as tall as mountains, blotting out the sky. There Anamuht strode veiled in sheets of flame from head to toe, lightning bolts in her hands.

From time to time, we caught glimpses of them in the deep distance, but not today.

My weight shifted as I looked back, and my left foot dislodged a pebble. It rattled down the cliff.

Far below, the fat merchant and his escort were arriving. The merchant glanced up. Rivulets of sweat ran down his plump cheeks, but his gaze was unexpectedly sharp. He glanced away and twitched the long sleeves of his robes to better cover his hands on the reins. His mount tossed its head in a fretful response and something tickled at my thoughts, making me frown.

Let your mind be like the eye of the hawk . . .

But then Brother Jawal’s hand was on my elbow, urging me backward. “Come,” he said. “It’s almost time to take up our posts.”

The sounding-bowl rang as we withdrew, a single chiming note that seemed to hang forever in the bright air.

As was the custom, the supplicant was given leave to rest and refresh himself before attempting the trial. The fat man, I thought, would be grateful for such a respite even if they had made camp within an hour’s ride of the fortress. I wondered if it were true that he would attempt a bribe.

His hands, though . . . why did he seek to conceal his hands?

I shook my head; whatever thought I’d had was gone. I had made my stance at the third post in the Hall of Proving. It was warm, the breath of the desert stirring faintly here. Behind me, the cavern opened onto daylight.

Daylight; for the supplicant, freedom and life.

For me, it meant I would be silhouetted in light, giving the fat man an advantage. Oh, but he wouldn’t get this far, would he?

No, it seemed impossible. Brother Jawal was fast and ruthless; the fat man stood no chance of defeating him in combat or evading him with speed. Even if by some miracle he passed the first post, Brother Merik stood at the second post. He was not as fast as Brother Jawal, but he was a seasoned warrior who fought with deadly efficiency, never a single move wasted.

Still, I had to be prepared. “Pahrkun, I am your instrument today,” I whispered, drawing my dagger. My hand was sweating and slippery on the hilt. “If it is your will, use me.”

Silence.

Hands, the fat man’s hands.

Maybe it was another odd custom of city folk. My mind drifted, drifted like the hawk’s feather.

Zariya.

I closed my eyes, letting my gaze adjust to the darkness before me. When I opened them, I could make out the crooked stalagmite at the bend that marked the threshold between the second and third posts.

The sounding-bowl rang again, its chiming note muted by the stone walls around me. I heard Brother Saan’s voice announcing that the Trial of Pahrkun had begun.

I heard Brother Jawal begin to utter his tribal war-cry, high and fierce—but then the cry was abruptly muffled. I listened for the sound of clashing blades and heard nothing. My palms began to itch and I had a taste like metal in my mouth. Brother Jawal . . . no. It was not possible.

I waited.

In the darkness ahead of me, there was a faint, familiar sound, followed by an unexpected flare of light that nearly made me cry out in alarm. Blinking ferociously against the dazzle behind my eyes, I heard a thump and a grunt of pain, then the sound of Brother Merik’s voice uttering low curses and the clatter of a blade against . . . what? Not metal, but stone, I thought.

The air around me eddied.

He was coming.

The fat man was coming, and now, at last I was afraid. My knees shook and every fiber of my being urged me to hide, hide and conceal myself in the shadows, and let the fat man pass.

No.

There was no honor in hiding. And yet here at the third and final post, how was I to prevail against a man with the skill and cunning to make it past Brother Jawal and Brother Merik? The dagger in my hand felt puny and inadequate; I felt puny and inadequate.

I recalled Brother Saan’s words again: What is a warrior’s first and greatest weapon?

I shoved my dagger into my sash and unwound the heshkrat that was tied around my waist; three lengths of thin rope, the strands joined at one end, stones knotted at the other. It was a hunting weapon, not a combat weapon; one used by tribesmen to bring down antelope in the desert.

Brother Jawal had taught me to use it. I prayed to Pahrkun to guide my hand.

The flare of light around the bend in the cavern had died and something was moving in the shadows. A man; not a fat man in robes, but a slender one clad in close-fitting black attire, staying close to the walls and walking as soft-footed as a desert cat, with throwing daggers in both his hands.

I saw him see me and throw with one hand and then the other, flicking his daggers in my direction as quick as the blink of an eye, but the wind of his motion warned me and I was already moving, the ropes of my heshkrat whirling overhead; one turn before I loosed it, aiming low.

The man was moving too, but the heshkrat was designed to bring down prey on the run. It tangled his legs and he fell hard.

A gust of wind blew through the Hall of Proving and a hard, fierce joy suffused me. Drawing my dagger, I fell on the man, thinking to stab him in the jugular. Agile as a snake, he twisted beneath me and the point of my dagger struck the stone floor of the cavern, jarring my arm.

I swore.

Still, he was unarmed, and if I could only stab him before his greater strength prevailed . . . but no, as we grappled, somehow his hands were no longer empty, somehow there was a cord wrapped around my throat, and his hands were drawing the ends tight. His hands; his strong, slender hands. That was why he’d hidden them. They were not the hands of a fat man. It had been a disguise.

Interesting.

It was a pity that my throat was burning, my chest was heaving for lack of air, and my vision was blurring.

“Watery hell!” The not-fat man’s eyes widened. “You’re just a kid!” He let go the cord, kicked free of the ropes of the heshkrat, and backed away from me; backed away toward sunlight and salvation. “I’m not killing a fucking kid!” he called out.

I got to my hands and knees, wheezing.

Brother Saan entered the Hall of Proving, his features as calm and grave as ever. He regarded the not-fat man who now stood beyond the threshold of the cavern in broad daylight, wind ruffling his hair. “I am pleased to hear it,” he said in his mild voice. “Whatever sins you have committed, Pahrkun the Scouring Wind has cleansed you of them. Welcome to the brotherhood.”

TWO

Brother Merik was merely injured, having taken a throwing dagger to the forearm he raised against the unexpected brightness; a dagger expertly placed between the steel prongs of the kopar. After that, the supplicant had slipped past him while he blundered blindly in the darkness, his sword clattering against the stone walls.

Brother Jawal was dead, his neck broken. The supplicant had flung his robe over him and taken him by surprise.

The impossible had come to pass.

We laid his body, stripped bare save for a loincloth, on a bier atop a high plateau. Once the hawks and vultures and carrion beetles, all creatures of Pahrkun, had picked the flesh from his bones, they would be returned to his clan.

Although I had no right to be angry, I was; angry at the supplicant for his trickery, angry at Brother Jawal for letting himself get killed. I was angry at myself for seeing too late through the supplicant’s disguise, angry at myself for failing to kill him, angry that I owed him my life.

That night the king’s guardsmen dined with us. I saw them glance at me with open curiosity, but the mood was a mixture of somber mourning and quiet acceptance, and they did nothing to disturb it.

The supplicant—whatever his name had been, he was a man with no name now, and would remain thus until Brother Saan gave him a new one—kept his head low and ate quickly and deftly. Out of his disguise, he looked younger than I had first thought. Otherwise there was nothing remarkable to the eye about the nameless man, and it seemed wrong that such an ordinary-looking fellow should be responsible for killing Brother Jawal.

When our meal of stewed goat and calabash squash had been consumed, Brother Saan poured cups of mint tea. “By your skills at deception and subterfuge, I take it you are a member of the Shahalim Clan from the city of Merabaht,” he said, passing a cup to the nameless man. “It is said that they are thieves and spies without peer.”

“I was,” he said in a curt tone.

Brother Saan blew on his tea. “I thought the Shahalim never got caught.”

The nameless man grimaced. “Never spite a Shahalim woman, Elder Brother. I was betrayed.” He lifted his cup, then set it down. “That’s the princess’s shadow, isn’t it?” He pointed at me. “I can’t believe you damned near let me kill a Sun-Blessed’s shadow.”

There were a few murmurs of agreement, and I flushed with embarrassment and anger.

“Yet you did not,” Brother Saan said calmly. “It seems Pahrkun wishes you to teach Khai your ways.”

The nameless man stared at him. “Teach clan secrets to an outsider? Never. It is forbidden.”

Brother Saan took a sip of his tea. “Your former clan betrayed you. The Brotherhood of Pahrkun is your clan now.”

The nameless man got to his feet. “I won’t—”

The six guards and several of the brothers rose, hands reaching for sword hilts. The nameless man sat back down.

“I don’t want to learn his ways!” The words burst from me. “They’re nothing but trickery! It’s dishonorable!”

Brother Saan eyed me. “Khai, it is your grief that speaks. Go, retire for the night. We will speak more of this on the morrow.”

I hesitated.

“It is an order, young one,” he said.

I went reluctantly. Behind me, I could hear the tenor of the conversation change. There was a part of me that was tempted to creep back and listen, but that seemed the sort of unworthy thing the nameless man would do, and so I obeyed Brother Saan and retired to my chamber.

In the morning, Brother Jawal was still dead and my anger was still with me. Brother Ehudan dismissed me within mere minutes. “You’re not fit to study today,” he said irritably. “Take your foul temper elsewhere. Take it out on the spinning devil.”

Since it was as good a suggestion as any, I went.

The spinning devil was a contraption of the nomadic tribesfolk, designed to train young men in the art of weaponless combat they called “thunder and lightning.” It consisted of a tall, sturdy central shaft planted firmly in the earth—or in this instance, wedged firmly in a deep crevice in the floor of a cavern—and four leather-bound paddles of varying length that spun around it like wheels around the axle of a cart. It was a cunning device, and one that Brother Jawal said could be easily disassembled and transported. He was the one who taught me to use it, as he taught me to throw the heshkrat.

A grown man could set all four paddles in motion so that the device resembled the spinning dust devils from which it took its name. I could only strike the lower two with any force, but it was enough for now. Boom, I threw a punch with my fist that was thunder, and the paddle spun; flash, I struck an angled blow with the side of my hand that was lightning, and the paddle spun the other way. Boom, a direct forward kick to the lowest paddle, and flash, a side kick with the blade of my foot.

Boom, flash flash, boom boom flash, flash boom boom, flash flash. The spinning devil spun and spun and creaked, the paddles a blur. Brother Jawal had told me that the nomads invented thunder and lightning many, many years ago as a way for hot-blooded young men to fight without killing one another.

Once they got very, very good at it, that didn’t always hold true.

Brother Jawal said that there was a ritual to challenging a tribesman to fight with thunder and lightning, a ritual that involved clapping your hands and stamping your feet. Clap-clap-stamp on the right, clap-clap-stamp on the left. If you wanted to insult your opponent and imply that he was unworthy, you clap-clap-stamped twice on the left instead. He had laughed when he told me that, and although he did not say it, I knew that he had done it, and won his challenge.

And now Brother Jawal was dead at the hands of a nameless man who knew nothing of ritual or honor.

Flash flash flash boom boom.

I fought the spinning devil with grim determination, sweat stinging my eyes and dampening my hair. I was still battling it when Brother Saan entered the training chamber, a rolled wool carpet under one arm. When I paused, he gestured for me to continue and set about unrolling the carpet. I launched a final flurry of blows at the spinning devil, then stepped back, panting hard. The paddles continued to drift in circles, creaking slowly to a halt.

Brother Saan sat cross-legged on the carpet awaiting me, a leather-wrapped bundle before him. I folded my legs to sit opposite him, pressing my palms together and touching my brow. My breathing sounded loud in the quiet cavern. Brother Saan waited for me to find stillness. Except for the slight rise and fall of his chest, he might have been carved out of stone. Even though time had touched his flesh with the slackness of age, the muscles beneath were lean and ropy.

At last my breathing slowed, and I found stillness. A shaft of sunlight angled through the cavern from an aperture above us and dust motes sparkled within it. All was quiet.

“Once upon a time, there were stars in the night sky,” Brother Saan began, then paused when an involuntary sound escaped me. I was in no mood for tales of wonder from days of yore.

“Forgive me, Elder Brother,” I murmured. “I meant no disrespect.”

He waited another long moment. “Once upon a time, there were stars in the night sky,” he began again. “Thousands and thousands of them, shining as bright as diamonds. And those stars were the flashing eyes and teeth and the fierce beating hearts of the thousand children of Zar the Sun, Nim the Bright Moon, Shahal the Dark Moon, and fickle Eshen the Wandering Moon, and we revered them all. The stars in the night sky let us guide our steps on land, and allowed mariners at sea to find their way on the four great currents.” He lifted one finger. “But the children of heaven were not content to keep their places while the Sun and the Moons traveled freely, and so they rose up and sought to overthrow their parents. Chaos reigned in heaven; fiery stones fell to earth in the battle, and the great currents and tides ran wild in the seas.”

I nodded; all this I knew.

“Until Zar the Sun said enough.” Brother Saan made a sweeping gesture. “In anger, he cast down his thousand rebellious children and they fell from the heavens to earth. Here they are bound and here they remain, and the night sky is empty of stars.” He regarded me. “Do you suppose that all the fallen children of the heavens shall remain content that it should ever be thus?”

“I…” I blinked; I had not anticipated the question. “I beg your pardon, Elder Brother. What?”

Brother Saan rested his hands on his knees. “Here in Zarkhoum, we are fortunate. Even though they raised their hands against him, Anamuht the Purging Fire and Pahrkun the Scouring Wind are two of Zar’s best-beloved children; his brother and sister twins born to different mothers,” he said. “Zar the Sun saw to it that they fell to the land where they might be the first of his children he gazes upon when he begins his journey across the sky, and the Sacred Twins have pledged to protect the land to which they are bound, and never again defy their father.”

All this, too, I knew. “Do you say this is untrue elsewhere?” It was a difficult idea for my mind to encompass; although I had been taught that there were other realms and other gods beneath the starless skies, the desert and the Sacred Twins were all that I had ever known. I could not imagine other gods.

His gaze was troubled. “I fear it may be so. The priestesses of Anamuht claim that there is a prophecy that when darkness rises in the west, one of the Sun-Blessed will stand against it.”

My breath caught in my throat. “Zariya?”

“It is highly unlikely.” Brother Saan’s voice took on a rare acerbic note, and his gaze cleared. “The daughters of the House of the Ageless are cherished and sheltered. Still, when one of the Sun-Blessed is born with a shadow, we must avail ourselves of every form of training that presents itself.”

My sullen anger, forgotten in my battle with the spinning devil, stirred. “You speak of these Shahalim.”

“I do.” Brother Saan gave me a sharp look. “Do you know what happened the last time a shadow was born?”

I shook my head. “Only that it happened a hundred and fifty years before my birth, Elder Brother.”

“Yes, and some forty years ago, his Sun-Blessed charge died in his care,” he said simply.

I tallied the figures in my head and frowned. “But how could that be? He would have been a hundred and twenty.”

“The shadow of one of the Sun-Blessed is allowed to partake of the rhamanthus seeds,” Brother Saan said. “He did not begin to age until his charge died.”

My head was spinning like the spinning devil. “Forgive me, Elder Brother, but what has that to do with the Shahalim?”

He did not answer my question directly. “I myself was not yet born when that shadow’s training took place,” he said. “But I was newly appointed as Seer when his charge died, and it fell to me to question him about what happened. The shadow was a broken man, filled with bitterness and fury.”

“Why?” I whispered.

“Because he failed to prevent it.” Brother Saan gazed into the distance. “His charge was poisoned.”

I let out my breath in a hiss.

“Yes.” Brother Saan nodded. “A most dishonorable means of attack; and yet, it proved effective. Brother Vironesh—for that was the shadow’s name—had no means by which to anticipate it. He spoke passionately to me about the need for honor beyond honor.”

“Honor beyond honor,” I echoed.

He nodded again. “That is what it meant to him to keep his charge alive at any cost. Honor beyond honor. We failed to prepare him for it. And so I do not think it is any accident that Pahrkun has accepted one of the Shahalim into our brotherhood; one from whom you might learn a great many things we cannot teach you. They are sneaks and thieves, but they are highly skilled in their arts. These are things that you might reckon dishonorable; only know, they are in the service of honor beyond honor. As a shadow, nothing else must matter to you.”

I was silent.

“Do you understand?” Brother Saan asked me.

Bowing my head, I touched my brow with the thumbs of my folded hands. “Yes, Elder Brother. I do.”

“Good.” He unfolded the bundle before him to reveal Brother Jawal’s fighting weapons; his sharp-whetted yakhan with its worn leather-wrapped hilt and curved blade, and the three-pronged kopar. “You have stood a post in the Trial of Pahrkun. It is only fitting that these are yours now.”

I took them up with reverence, feeling the weight of them. I could not resist a few trial passes, weaving the yakhan in the complicated figure-eight pattern favored by the desert tribesfolk, spinning and reversing the kopar so its prongs lay flat along my forearm. It made my wrists ache.

Brother Saan smiled, his eyelids crinkling. “Here,” he said, plucking two more items from his bundle. They were fist-sized rocks.

I eyed him. “Elder Brother?”

“Squeeze them,” he said, fitting actions to words to demonstrate. Beneath his wrinkled skin, the muscles in his wrists and forearms stood out like cords. “Three thousand times a day.”

I inclined my head. “Yes, Elder Brother.”

He folded his empty bundle, rolled his carpet, and rose. “On the morrow, after your lesson with Brother Ehudan, you will begin training with Brother Yarit, and obey him in every particular whether it seems honorable or not.”

I glanced up at him. “Brother Yarit?”

“The Shahalim.” He smiled again, this time wryly. “We held a naming ceremony for him today. Whether he likes it or not, and at the moment, he likes it no more than you do, he is one of us now.”

A thought came to me as I rose. “Elder Brother … are there other shadows yet among the living?”

“No.” He shook his head. “The last born before Vironesh was some seven hundred years ago. His charge came into khementaran centuries ago.”

“Khementaran?” I did not know the word.

“The point of return.” Brother Saan rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “Members of the House of the Ageless live very long lives, if those lives are not cut short by violence or illness, but they do not live forever. Sooner or later, each comes to the point they call khementaran, when they desire to return to the natural rhythms of the mortal world, to allow themselves to age with the passing of the seasons.”

I eyed him, thinking it seemed unlikely to me.

He favored me with another wry look in return. “It may be that you will find out for yourself one day, young Khai.”

I tucked that thought away to ponder later, but I was not quite done yet. “Elder Brother … what became of Vironesh? The broken shadow?”

“Ah.” His expression changed. “Well you might inquire, for I have been endeavoring to learn that very thing. There are rumors. It may be that he yet lives, for his body was decades younger than my own when he began to age.” He shook his head. “But if it is so, thus far he does not wish to be found.” He raised his brows at me. “Have you other questions for me today, young Khai?”

I touched my forehead with one thumb, Brother Jawal’s weapons tucked under my other arm. “No, Elder Brother.”

“Very good.”

I returned to my chamber to stow my new possessions and began squeezing rocks, but it was later than I’d reckoned. The midday heat was oppressive, and my limbs were weary from my battle with the spinning devil. By the time I reached five hundred, my eyelids were growing heavy. Still, I kept going until I reached a thousand. I would do the rest after a midday nap, when the air would be cooler.

Thoughts drifted through my mind; drifted, drifted like a hawk’s feather on the wind. Falling stars, rhamanthus seeds. Khementaran, the point of return … who would seek to return to death and decay?

And yet death and decay were a part of nature and the purview of Pahrkun the Scouring Wind …

Poison; a broken and bitter shadow, his charge slain by dishonorable means. Who were the enemies of the Sun-Blessed? Who would seek their lives?

One day I would know.

Whatever might come, I resolved that I would strive to attain honor beyond honor. Brother Jawal, I thought, would understand.

Copyright © 2018 by Jacqueline Carey

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Duty takes precedence over all else, and I knew what it meant to fail at it far better than my brother ever could.

Duty takes precedence over all else, and I knew what it meant to fail at it far better than my brother ever could. opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window