New Releases: 6/26/18

New from Morgan Llewelyn, Patrick S. Tomlinson, Hannu Rajaniemi, and others!

New from Morgan Llewelyn, Patrick S. Tomlinson, Hannu Rajaniemi, and others!

Blood pumping, heart racing, mind busy — these fast-paced thrillers will keep you warm (and distracted) during the freezing weather of winter!

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in October! See who is coming to a city near you this month.

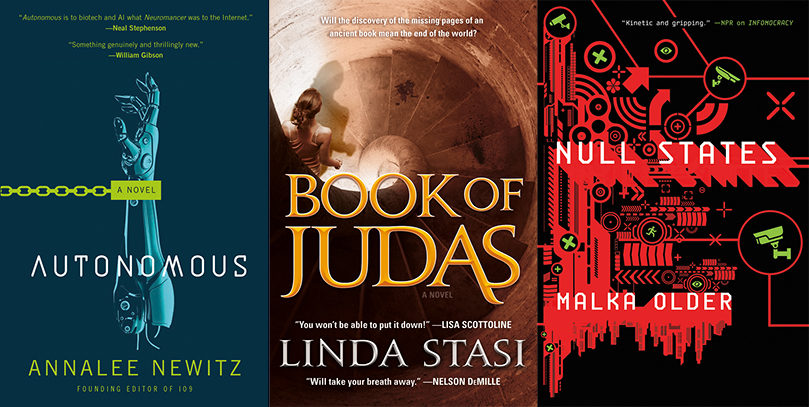

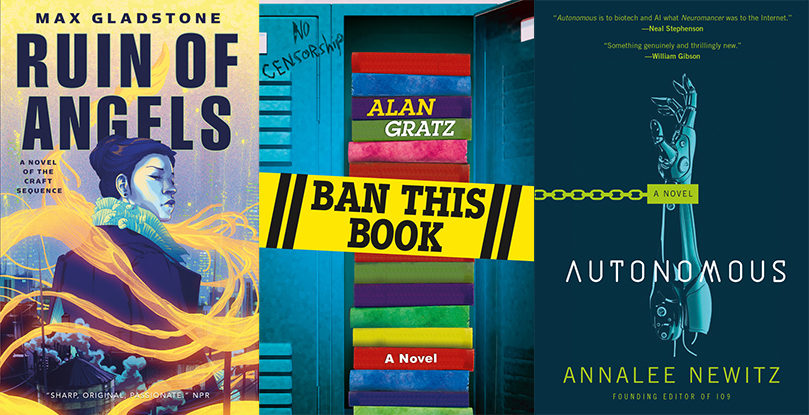

New from Annalee Newitz, Malka Older, Linda Stasi, and Brandon Sanderson!

Watch a trailer for Book of Judas, a new thriller by Linda Stasi!

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in September! See who is coming to a city near you this month.

Pick up the ebook edition of The Sixth Station by Linda Stasi, on sale for only $2.99. This offer will only last for a limited time, so order your copy today!

A secret gospel that may challenge the very roots of Christianity has been stolen, and it’s up to Alessandra Russo to find it. Book of Judas will become available September 19th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Book Trailer: The Sixth Station by Linda Stasi The Sixth Station by Linda Stasi Some say Demiel ben Yusef is the world’s most dangerous terrorist, personally responsible for bombings and riots that have claimed the lives of thousands. Others insist he is a man of peace, a miracle worker, and possibly even the Son of…