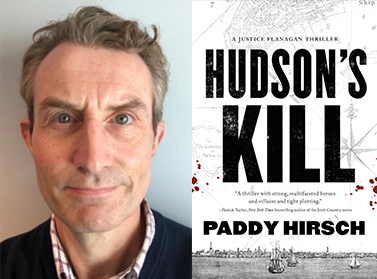

Paddy Hirsch’s upcoming novel, Hudson’s Kill, tells the story of the murder of a young black girl in 1803 New York City. While Hirsch’s book is fictional, he did a lot of research on the real murders that happened in the city at the turn of the 19th century. Below he shares what he learned.

By Paddy Hirsch

When the Revolutionary War ended in 1783 and the King’s soldiers departed for England, the King’s laws went with them. Good riddance, most people said. British rule had been oppressive, restrictive and expensive.

But at the turn of the 19th Century, New York was under pressure: every month, thousands of people decanted from transatlantic ships onto the wharves of the East and Hudson River. But there weren’t enough jobs, and many of the newcomers turned to crime: theft, prostitution, protection, arson, counterfeiting and thuggery.

The city’s merchants cried out for some kind of police force to protect their investments and livelihoods, but a majority of the power brokers in New York refused. They remembered how the British kept a standing army within the city’s limits, and used it to keep the people in line. What was the difference between that and a uniformed police? It was an infringement of liberty, they argued.

And then the murders began.

The Murder of Guilelma Sands

It’s unlikely that Gulielma Elmore Sands was the first woman murdered in post-colonial New York, but the killing itself, the discovery of her body and the subsequent trial were all firsts for the city in their own ways.

From the moment Sands’ body was discovered on a cold January morning in 1800, stuffed into a well, strangulation marks around her neck, the case was a media sensation. All of New York’s newspapers – all relatively new at the turn of the century – fought to cover The Manhattan Well Murder in all its lurid detail. Rumors abounded about the character of the woman and the identity of her killer, but a narrative quickly emerged: 21-year-old Sands, a Quaker, lived in a boarding house owned by a cousin on Greenwich Street; she had developed a friendship with a fellow boarder, Levi Weeks; over time the friendship had developed into a secret romance; Sands had become pregnant; they were planning to elope on the evening of December 22, 1799; Sands had left the boarding house, wrapped up against the freezing cold in a shawl, hat and earmuffs; she was never seen alive again.

Weeks was promptly arrested. His trial was set for March 31, 1800. New York’s newspapers – and its populace – were full-throated and almost unanimous in their conviction that Weeks was guilty. Not quite unanimous, because there was a handful of New Yorkers who believed in, and held out for, due process and the presumption of innocence. They included Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, both of who defended Weeks in court in the first American murder trial to be entirely documented by a stenographer.

It later emerged that Burr and Hamilton may have agreed to defend Week’s for rather grubbier reasons than their love for the law. They were both in debt to a man named Ezra Weeks, a powerful and wealthy contractor who also happened to be Levi Week’s brother. Perhaps it was that whiff of cynicism that galvanized the newspapers. Perhaps it was the courtroom trickery practiced by Burr and Hamilton’s partner, a specialist in criminal law named Brockholst Livingston who eventually became a Supreme Court jurist. Whatever the cause, when the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty, and the judge announced an acquittal, the newspapers howled. The people howled louder. Fearing for his life, Levi Weeks had to flee the city.*

The media coverage of the Manhattan Well Murder lent weight to arguments that New York, as it grew, was becoming increasingly lawless. The city was essentially unpoliced, other than by a night watch that kept an eye out for fires, and a small team of marshals and constables, who assisted the courts in rounding up witnesses and carrying out judgments. It wasn’t enough, but there was still considerable resistance to creating a police force. Instead, the Mayor, Edward Livingston, expanded the Marshals service, and in 1802 appointed a High Constable, Jacob Hays.

Hays rotated into and out of the post of High Constable several times until 1810, when he was appointed for a term that ended up lasting 35 years. As the crime rate increased in the early 1800s, Hays was able to apply increasing pressure on the Mayor’s office to expand the constabulary. But in 1836, his efforts were given a particular boost in by something that was by no means exceptional at the time: the murder of a prostitute.

The Murder of Helen Jewett

Prostitution was a common form of employment for women in New York in the early 1800s. It was also very high risk. Prostitutes were more likely to die of disease, alcohol abuse or starvation than murder, but violent death wasn’t uncommon. What made the murder of Helen Jewett so remarkable was the media coverage. And the coverage by one publication in particular.

James Gordon Bennett had founded the New York Herald in 1835, and he was desperate to make his newspaper stand out in a crowded field. When Helen Jewett – born Dorcas Doyen in Augusta Maine – was found murdered in her boudoir, the penny press flocked to tell the story. Instead of covering the story the usual way, giving it shared space with other news of the day, Bennett decided to do something different with the Herald. He put every reporter he had on the story, and blanketed coverage. His people interviewed everyone and anyone with the flimsiest connections to the case; he wrote opinion, published exclusives, indulged in speculation, exaggeration, even fabrication.

The tactic paid off. The Herald became a must-read. And, in a way, the murder itself was less important than what came after. Jewett was a celebrated, high-end prostitute who was killed by a blow to the head. Her alleged assailant, a man named Richard Robinson, was arrested, tried and acquitted on the basis of an alibi. Like Levi Weeks, 35 years before, Robinson fled the city. He died not long after.

But the Herald was not finished with the crime. A year later, Bennett published a front page story using the Jewett murder as a benchmark to measure the rising murder rate in the city. As the article put it: “…the Demon or Fiend of Murder has stalked through the streets of our beautiful city, unchecked, unscathed.” The article detailed recent murders: of “a young German girl, innocent and virtuous”, killed and hurled off the Battery; of “a respectable white man, murdered by four negroes”; of “an industrious stevedore”, murdered and thrown into the river. The story hinted at corruption, of connected offenders protected by people in high office, and warned that if things carried on thus, “the young and “innocent” boys about town will begin to think they can commit murders with impunity.”

Other newspapers piled on, and the pressure on the Mayor’s office became intense. And then, on July 28, 1841, the body of a young woman was found floating in the Hudson river, near Hoboken, and the pot – and the city – boiled over.

The Murder of Mary Rogers

Mary Rogers was a young Connecticut-born woman who worked in a New York tobacconist. She was a noted beauty, such that the New York Herald published several pieces about her, including a letter from a customer saying he had spent an entire afternoon exchanging teasing glances with her, and a poem written by an admirer extolling the heavenliness of her smile and the starriness of her eyes. In 1838, the New York Sun reported she had gone missing, and left a suicide note. The next day, however, after a spurt of media attention, Rogers reappeared, saying she had merely been visiting a friend. Reports suggested the entire event was a publicity stunt perpetrated by the tobacconist, John Anderson.

Three years later, Rogers was in the headlines again. But this time there was no hoax. “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” was found dead in the water, with bruises around her throat. It wasn’t merely her comeliness that attracted attention: the tobacconist was patronized by several prominent literary figures, including Edgar Allan Poe, as well as large number of New York’s newspapermen. The latter worked themselves into a furious lather, publicizing rumor after rumor as the case dragged on. The killer was one man, Rogers’ fiancé, Daniel Payne; it was several men, members of a New York street gang; it was a spurned customer; an unidentified officer. No story, no matter how unlikely, was left untold, and updates on the murder occupied the front pages of the papers for weeks.

No one was arrested. Then Daniel Payne killed himself. The newspapers published editorials castigating the mayor and the courts for their negligence, which had allowed New York to become a sink of lawlessness, in which a criminal community operated with almost complete freedom, unmolested by a skeleton crew of half-drunk watchmen and poorly-paid constables.

The barbs sunk home. Within two years, the New York State Government had passed the Municipal Police Act, abolishing the old night watch system and allowing cities to create a police force. A year later, in May 1845, the New York Police Department was born.

Order Your Copy of Hudson’s Kill:

True crime fans can still visit the final resting place of poor Guilelma – maybe. On the frozen morning in January 1800 when her body was found, the well was located in the middle of a damp area of wasteland, known as Lispenard’s Meadow. The meadow was soon to be reclaimed, filled in and developed into what is now called SoHo. For many years, the owners of a restaurant located at 129 Spring Street in Soho claimed that a brick well in the basement of their building was the very same well that Guilelma’s body had been found in. People still trek to the building – now the site of a clothing store called COS – to visit and photograph the well. But experts are skeptical. The structure is too small to be a well, they say – it’s more the size of a cistern. Moreover, wells built in 1799 were generally made of stone, not brick. Still, it’s a great story, and COS has done a great job of maintaining the structure. Basement floor. Beside the sweaters.