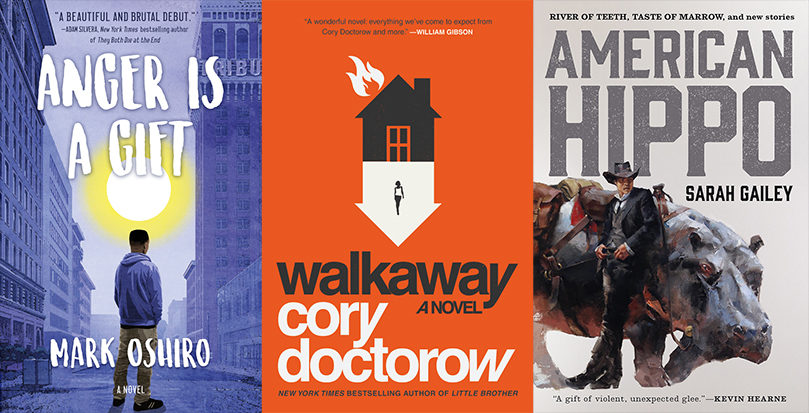

New Releases: 5/22/18

New from Mark Oshiro, Cory Doctorow, Sarah Gailey, and others!

New from Mark Oshiro, Cory Doctorow, Sarah Gailey, and others!

As technology marches ever forward, Walkaway author Cory Doctorow ponders how we can be masters of our computers instead of the other way around.

From New York Times bestselling author Cory Doctorow, an epic tale of revolution, love, post-scarcity, and the end of death, available in paperback on May 22nd.

Here are some last minute book recommendations for the sci-fi fans in your life.

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in June! See who is coming to a city near you this month.

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in May! See who is coming to a city near you this month.

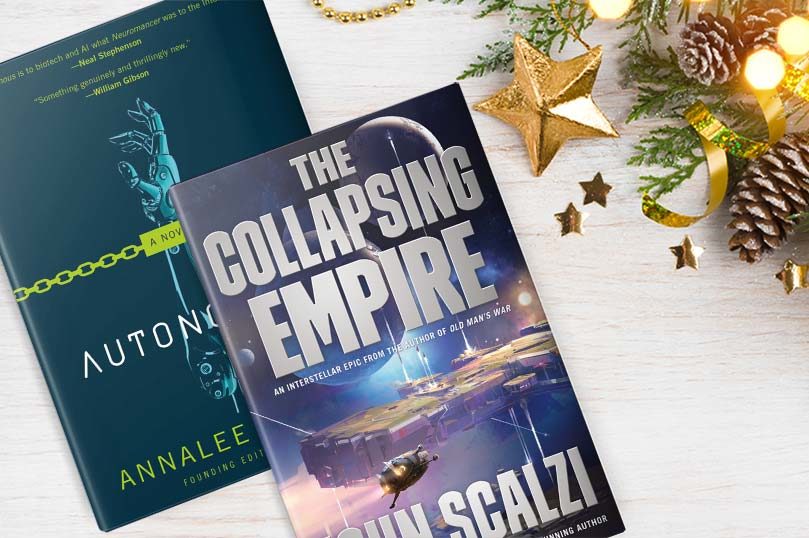

New from Brian Staveley, Marie Brennan, Cory Doctorow, and more!

As technology marches ever forward, Walkaway author Cory Doctorow ponders how we can be masters of our computers instead of the other way around.

Tor/Forge authors are on the road in April! See who is coming to a city near you this month.

From New York Times bestselling author Cory Doctorow, an epic tale of revolution, love, post-scarcity, and the end of death. Walkaway will be available April 25th. Please enjoy this excerpt.